Why Illyrian King Agron and Queen Teuta Came to a Bad End and Who Was Ballaios?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montenegro Old and New: History, Politics, Culture, and the People

60 ZuZana Poláčková; Pieter van Duin Montenegro Old and New: History, Politics, Culture, and the People The authors are focusing on how Montenegro today is coming to terms with the task of becoming a modern European nation, which implies recognition not only of democracy, the rule of law, and so forth, but also of a degree of ‘multiculturalism’, that is recognition of the existence of cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities in a society that is dominated by a Slavic Orthodox majority. In his context they are analyzing the history of the struggle of the Montenegrin people against a host of foreign invaders – after they had ceased to be invaders themselves – and especially their apparently consistent refusal to accept Ottoman sovereignty over their homeland seemed to make them the most remarkable freedom fighters imaginable and led to the creation of a special Montenegrin image in Europe. This im- age of heroic stubbornness and unique martial bravery was even consciously cultivated in Western and Central Europe from the early nineteenth century onwards, as the Greeks, the Serbs, the Montenegrins and other Balkan peoples began to resist the Ottoman Empire in a more effective way and the force of Romantic nationalism began to influence the whole of Europe, from German historians to British politi- cians, and also including Montenegrin and Serbian poets themselves. And what about the present situa- tion? The authors of this essay carried out an improvised piece of investigation into current conditions, attitudes, and feelings on both the Albanian and the Slavic-Montenegrin side (in September 2012). key words: Montenegro; history; multiculturalism; identity; nationalism; Muslim; Orthodox Montenegro (Crna Gora, Tsrna Gora, Tsernagora) is a small country in the Western Balkans region with some 625,000 inhabitants,1 which became an independent nation in 2006 and a can- didate-member of the EU in 2010. -

Illyrian Religion and Nation As Zero Institution

Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 3, No 1 (2016) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 Illyrian religion and nation as zero institution Josipa Lulić * Abstract The main theoretical and philosophical framework for this paper are Louis Althusser's writings on ideology, and ideological state apparatuses, as well as Rastko Močnik’s writings on ideology and on the nation as the zero institution. This theoretical framework is crucial for deconstructing some basic tenants in writing on the religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia, and the implicit theoretical constructs that govern the possibilities of thought on this particular subject. This paper demonstrates how the ideological construct of nation that ensures the reproduction of relations of production of modern societies is often implicitly or explicitly projected into the past, as trans-historical construct, thus soliciting anachronistic interpretations of the material remains of past societies. This paper uses the interpretation of religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia as a case study to stress the importance of the critique of ideology in the art history. The religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia has been researched almost exclusively through the search for the presumed elements of Illyrian religion in visual representations; the formulation of the research hypothesis was firmly rooted into the idea of nation as zero institution, which served as the default framework for various interpretations. In this paper I try to offer some alternative interpretations, intending not to give definite answers, but to open new spaces for research. Keywords: Roman sculpture, province of Dalmatia, nation as zero institution, ideology, Rastko Močnik, Louis Althusser. -

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

Τhe Danger of Participating in the Heavy Games of the Ancient Olympics

Available online at www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library European Journal of Sports & Exercise Science, 2019, 7 (1): 1-6 (http://www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com) ISSN:2278–005X The Danger of Participating in the Heavy Games of the Ancient Olympics Andreas Bourantanis* Department of Sports Science and Physical Education, Democritus University of Thrace, University of Dundee, United Kingdom; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Through the present, we seek to stimulate the interest of researchers and practitioners at the scientific and non- scientific level as well as the athletes and coaches associated with today's so-called combat sports to turn their concern to the proper adaptation of the ancient Greek Olympic ideal and Olympic Games. Our concern is to motivate the Olympic Committee with a view to reintroducing the sport to the Olympics Sports program. The Olympic Games were the oldest and most remarkable games of the ancient Greek world as a whole, among the events included in the sports program. The Olympics cultivated the body and the mind. Characterizing Pankration the ancient Greek writer Philostratus said it was the best of the Olympic Games. Although the Olympics were reconstituted, Pankration was not included in the sports program of modern Olympics. However this fact has left a gap in the schedule of the Olympics because it is paradoxical that the absence of the event that contributed to the Olympic Games’ prestige is absent. Research is to present some of the techniques that were used by the most famous athletes in antiquity while trying to investigate the dangers as well as the general danger of using these techniques and the damage to the human body. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Report of the First Season 'Dimal in Illyria' 2010

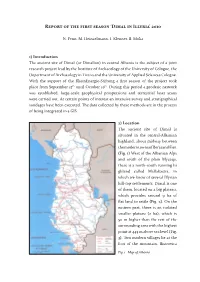

Report of the first season ‘Dimal in Illyria’ 2010 N. Fenn, M. Heinzelmann, I. Klenner, B. Muka 1) Introduction The ancient site of Dimal (or Dimallon) in central Albania is the subject of a joint research project lead by the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Cologne, the Department of Archaeology in Tirana and the University of Applied Sciences Cologne. With the support of the RheinEnergie-Stiftung a first season of the project took place from September 15th until October 19th. During this period a geodetic network was established, large-scale geophysical prospections and terrestrial laser scans were carried out. At certain points of interest an intensive survey and stratigraphical sondages have been executed. The data collected by these methods are in the process of being integrated in a GIS. 2) Location The ancient site of Dimal is situated in the central-Albanian highland, about midway between the modern towns of Berat and Fier. (Fig. 1) West of the Albanian Alps and south of the plain Myzeqe, there is a north-south running hi ghland called Mallakastra, in which we know of several Illyrian hill-top settlements. Dimal is one of them, located on a big plateau, which provides around 9 ha of flat land to settle (Fig. 2). On the eastern part, there is an isolated smaller plateau (2 ha), which is 50 m higher than the rest of the surrounding area with the highest point at 445 m above sea level (Fig. 3). Two modern villages lie at the foot of the mountain, Bistrovica Fig. 1 - Map of Albania REPORT OF THE FIRST SEASON ‘DIMAL IN ILLYRIA’ 2010 Fig. -

Światowit. Volume LVII. World Archaeology

Światowit II LV WIATOWIT S ´ VOLUME LVII WORLD ARCHAEOLOGY Swiatowit okl.indd 2-3 30/10/19 22:33 Światowit XIII-XIV A/B_Spis tresci A 07/11/2018 21:48 Page I Editorial Board / Rada Naukowa: Kazimierz Lewartowski (Chairman, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Serenella Ensoli (University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Italy), Włodzimierz Godlewski (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Joanna Kalaga ŚŚwiatowitwiatowit (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Mikola Kryvaltsevich (Department of Archaeology, Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Belarus), Andrey aannualnnual ofof thethe iinstitutenstitute ofof aarchaeologyrchaeology Mazurkevich (Department of Archaeology of Eastern Europe and Siberia, The State Hermitage ofof thethe uuniversityniversity ofof wwarsawarsaw Museum, Russia), Aliki Moustaka (Department of History and Archaeology, Aristotle University of Thesaloniki, Greece), Wojciech Nowakowski (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, ocznikocznik nstytutunstytutu rcheologiircheologii Poland), Andreas Rau (Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, Schleswig, Germany), rr ii aa Jutta Stroszeck (German Archaeological Institute at Athens, Greece), Karol Szymczak (Institute uuniwersytetuniwersytetu wwarszawskiegoarszawskiego of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland) Volume Reviewers / Receznzenci tomu: Jacek Andrzejowski (State Archaeological Museum in Warsaw, Poland), Monika Dolińska (National Museum in Warsaw, Poland), Arkadiusz -

Baseline Assessment Report of the Lake Ohrid Region – Albania Annex

TOWARDS STRENGTHENED GOVERNANCE OF THE SHARED TRANSBOUNDARY NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE LAKE OHRID REGION Baseline Assessment report of the Lake Ohrid region – Albania (available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/lake-ohrid-region) Annex XXIII Bibliography on cultural values and heritage, agriculture and tourism aspects of the Lake Ohrid region prepared by Luisa de Marco, Maxim Makartsev and Claudia Spinello on behalf of ICOMOS. January 2016 BIBLIOGRAPHY1 2015 The present bibliography focusses mainly on the cultural values and heritage, agriculture and tourism aspects of the Lake Ohrid region (LOR). It should be read in conjunction to the Baseline Assessment report prepared in a joint collaboration between ICOMOS and IUCN (available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/lake-ohrid-region) The bibliography includes all the relevant titles from the digital catalogue of the Albanian National Library for the geographic terms connected to LOR. The bibliography includes all the relevant titles from the systematic catalogue since 1989 to date, for the categories 9-908; 91-913 (4/9) (902. Archeology; 903. Prehistory. Prehistoric remains, antiquities. 904. Cultural remains of the historic times. 908. Regional studies. Studies of a place. 91. Geography. The exploration of the land and of specific places. Travels. Regional geography). It also includes the relevant titles found on www.scholar.google.com with summaries if they are provided or if the text is available. Three bibliographies for archaeology and ancient history of Albania were used: Bep Jubani’s (1945-1971); Faik Drini’s (1972-1983); V. Treska’s (1995-2000). A bibliography for the years 1984-1994 (authors: M.Korkuti, Z. -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Greece, the Land Where Myths Replaces Reality

GREECE, THE LAND WHERE MYTHS REPLACE REALITY (Myths about Epirus) What is myth and what does it serve? Myth is a narrative based usually on a false story which can not be used as a replacement of history, but sometimes myth might be considered a distorted account of a real historical event. The myth does not differ much from a folktale and usually the boundary between them is very thin. Myth must not be used to reconstruct, however in the ancient society of the so called “”Ancient Greeks”” myth was usually regarded as a true account for a remote past. Surprisingly this ‘tradition’ is descended to the Modern Greeks as well. They never loose the chance to use the myths and the mythology of a remote past and to pose them as their real ethnic history. This job is being done combining the ancient myths with the ones already created in the modern era. Now let’s take a look at two Greek myths, respectively one ancient and one modern, while our job is to prove that even these myths are respectively hijacked or created to join realities not related to each other, but unfortunately propagandized belonging to a real history, the history of the Greek race. Thus before we analyze and expose some of their myths which are uncountable, we are inclined to say that whatever is considered Greek History is completely based on mythical stories, whose reliability and truthiness is deeply compromised for the mere fact that is based on myths not only by the Modern Greeks and especially philhellenes, but even by the ancient authors. -

Hrvatska Povijest 20.Indd

IVAN MUŽIĆ HRVATSKA POVIJEST DEVETOGA STOLJEĆA BIBLIOTEKA POVJESNICE HRVATA 3 UREDNIK: Prof. Milan Ivanišević ZA NAKLADNIKE: Josip Botteri Zoran Bošković RECENZENTI I. IZDANJA: Dr. sc. Denis Alimov, Sveučilište u Sankt Peterburgu (Rusija) Dr. sc. Danijel Dzino, Sveučilište u Adelaide (Australia) Prof. dr. sc. Darko Gavrilović, Novi Sad Prof. dr. sc. Ivan Jurić, Zagreb Dr. sc. fra Bazilije Pandžić, Zagreb Prof. dr. sc. Ivo Rendić Miočević, Rijeka Akademik Radoslav Rotković, Herceg Novi LEKTOR: Mario Blagaić KOREKTURA: Vesela Romić PRIPREMA ZA TISAK: ACME PRIJELOM KNJIGE: Marko Grgić FOTOGRAFIJA NA KORICAMA: Spomen bana Branimira s hrvatskim etnonimom na arhitravu i zabatu predromaničke crkve na Crkvini u Šopotu kod Benkovca. Snimio Zoran Alajbeg, Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika u Splitu FOTOGRAFIJE U KNJIZI: Branimirov natpis iz Muća Snimio: Filip Beusan, Arheološki muzej u Zagrebu SVE OSTALE SLIKE U KNJIZI: Zoran Alajbeg, Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika u Splitu POVIJESNE KARTE IZRADIO: Tomislav Kaniški, Zagreb © Ivan Mužić, Čiovska 2, 21000 Split [email protected] www.muzic-ivan.info Pripremu i tiskanje dopunjenoga izdanja ove knjige u potpunosti su pomogli gospoda: Ivan Kapetanović (Ljubljana - Split), Josip Petrović (Zagreb), Zvonimir Puljić (Split) i Ante Sanader (Split) IVAN MUŽIĆ HRVATSKA POVIJEST DEVETOGA STOLJEĆA DRUGO DOPUNJENO IZDANJE MATICA HRVATSKA OGRANAK SPLIT NAKLADA BOŠKOVIĆ SPLIT 2007 Ženi Vlasti S A D R Ž AJ PREDGOVOR DRUGOM IZDANJU MUŽIĆEVE KNJIGE HRVATSKA POVIJEST DEVETOGA STOLJEĆA (MARIN ZANINOVIĆ) . 9 PROSLOV UZ PRVO IZDANJE KNJIGE HRVATSKA POVIJEST DEVETOGA STOLJEĆA IVANA MUŽIĆA (DANIJEL DZINO) . 19 UVOD O STAROSJEDITELJIMA KAO ETNIČKOM TEMELJU HRVATSKE ETNOGENEZE . .31 I. JAPODI, LIBURNI I DALMATI . 33 II. VLADAVINA GOTA NA TERITORIJU LIBURNIJE I DALMACIJE .