Classical Influences on the United States Constitution from Ancient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livy's View of the Roman National Character

James Luce, December 5th, 1993 Livy's View of the Roman National Character As early as 1663, Francis Pope named his plantation, in what would later become Washington, DC, "Rome" and renamed Goose Creek "Tiber", a local hill "Capitolium", an example of the way in which the colonists would draw upon ancient Rome for names, architecture and ideas. The founding fathers often called America "the New Rome", a place where, as Charles Lee said to Patrick Henry, Roman republican ideals were being realized. The Roman historian Livy (Titus Livius, 59 BC-AD 17) lived at the juncture of the breakdown of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. His 142 book History of Rome from 753 to 9 BC (35 books now extant, the rest epitomes) was one of the most read Latin authors by early American colonists, partly because he wrote about the Roman national character and his unique view of how that character was formed. "National character" is no longer considered a valid term, nations may not really have specific national characters, but many think they do. The ancients believed states or peoples had a national character and that it arose one of 3 ways: 1) innate/racial: Aristotle believed that all non-Greeks were barbarous and suited to be slaves; Romans believed that Carthaginians were perfidious. 2) influence of geography/climate: e.g., that Northern tribes were vigorous but dumb 3) influence of institutions and national norms based on political and family life. The Greek historian Polybios believed that Roman institutions (e.g., division of government into senate, assemblies and magistrates, each with its own powers) made the Romans great, and the architects of the American constitution read this with especial care and interest. -

ROMAN REPUBLICAN CAVALRY TACTICS in the 3Rd-2Nd

ACTA MARISIENSIS. SERIA HISTORIA Vol. 2 (2020) ISSN (Print) 2668-9545 ISSN (Online) 2668-9715 DOI: 10.2478/amsh-2020-0008 “BELLATOR EQUUS”. ROMAN REPUBLICAN CAVALRY TACTICS IN THE 3rd-2nd CENTURIES BC Fábián István Abstact One of the most interesting periods in the history of the Roman cavalry were the Punic wars. Many historians believe that during these conflicts the ill fame of the Roman cavalry was founded but, as it can be observed it was not the determination that lacked. The main issue is the presence of the political factor who decided in the main battles of this conflict. The present paper has as aim to outline a few aspects of how the Roman mid-republican cavalry met these odds and how they tried to incline the balance in their favor. Keywords: Republic; cavalry; Hannibal; battle; tactics The main role of a well performing cavalry is to disrupt an infantry formation and harm the enemy’s cavalry units. From this perspective the Roman cavalry, especially the middle Republican one, performed well by employing tactics “if not uniquely Roman, were quite distinct from the normal tactics of many other ancient Mediterranean cavalry forces. The Roman predilection to shock actions against infantry may have been shared by some contemporary cavalry forces, but their preference for stationary hand-to-hand or dismounted combat against enemy cavalry was almost unique to them”.1 The main problem is that there are no major sources concerning this period except for Polibyus and Titus Livius. The first may come as more reliable for two reasons: he used first-hand information from the witnesses of the conflicts between 220-167 and ”furthermore Polybius’ account is particularly valuable because he had serves as hypparch in Achaea and clearly had interest and aptitude in analyzing military affairs”2. -

Machiavelli and Republicanism in Elizabethan England

Griot : Revista de Filosofia, Amargosa - BA, v.21, n.2, p.221-236, junho, 2021 ISSN 2178-1036 https://doi.org/10.31977/grirfi.v21i2.2386 Recebido: 15/02/2021| Aprovado: 05/05/2021 Received: 02/15/2021 | Approved: 05/05/2021 MACHIAVELLI AND REPUBLICANISM IN ELIZABETHAN ENGLAND Marcone Costa Cerqueira1 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4539-3840 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The purpose of this succinct work is to present N. Machiavelli's classic republican view from his proposition of an inevitable paradox, the founding of an expansionist republic, difficult to govern, or the founding of a stable, but small and weak republic. Such a paradox, according to Machiavelli, should direct and condition all the constitutive devices of the republic when choosing what will be its destiny as a political body. The model of republic preferred by the Florentine will be the expansionist model of Rome, leading him to assume all the devices that gave this republic its power. From this presentation of the Machiavellian proposition, we will analyse the assimilation of republican thought in England from the Elizabethan period, as well as the political-social scenario that exists there. This itinerary will allow us to understand, in general, why classical republicanism was received on English soil from the perspective of establishing a mixed, stable government, thus favouring the spread of the Venice myth as a serene republic and delaying the use, even that mitigated, of the republican presuppositions expressed in the Machiavellian work that directed towards a Roman model. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

Rome. the Etymological Origins

ROME.THE ETYMOLOGICAL ORIGINS Enrique Cabrejas — Director Linguistic Studies, Regen Palmer (Barcelona, Spain) E-mail: [email protected] The name of Rome was always a great mystery. Through this taxonomic study of Greek and Latin language, Enrique Cabrejas gives us the keys and unpublished answers to understand the etymology of the name. For thousands of years never came to suspect, including about the founder Romulus the reasons for the name and of his brother Remus, plus the unknown place name of the Lazio of the Italian peninsula which housed the foundation of ancient Rome. Keywords: Rome, Romulus, Remus, Tiber, Lazio, Italy, Rhea Silvia, Numitor, Amulio, Titus Tatius, Aeneas, Apollo, Aphrodite, Venus, Quirites, Romans, Sabines, Latins, Ἕλενος, Greeks, Etruscans, Iberians, fortuitus casus, vis maior, force majeure, rape of the Sabine, Luperca, Capitoline wolf, Palladium, Pallas, Vesta, Troy, Plutarch, Virgil, Herodotus, Enrique Cabrejas, etymology, taxonomy, Latin, Greek, ancient history , philosophy of language, acronyms, phrases, grammar, spelling, epigraphy, epistemology. Introduction There are names that highlight by their size or their amazing story. And from Rome we know his name, also history but what is the meaning? The name of Rome was always a great mystery. There are numerous and various hypotheses on the origin, list them again would not add any value to this document. My purpose is to reveal the true and not add more conjectures. Then I’ll convey an epistemology that has been unprecedented for thousands of years. So this theory of knowledge is an argument that I could perfectly support empirically. Let me take that Rome was founded as a popular legend tells by the brothers Romulus and Remus, suckled by a she-wolf, and according to other traditions by Romulus on 21 April 753 B.C. -

The Concept of Mixed Government in Classical and Early Modern Republicanism

Ivan Matić Original Scientific Paper University of Belgrade UDK 321.728:321.01 141.7 THE CONCEPT OF MIXED GOVERNMENT IN CLASSICAL AND EARLY MODERN REPUBLICANISM Abstract: This paper will present an analysis of the concept of mixed government in political philosophy, accentuating its role as the central connecting thread both between theories within classical and early modern republicanism and of the two eras within the republican tradition. The first part of the paper will offer a definition of mixed government, contrasting it with separation of powers and explaining its potential significance in contemporary political though. The second part will offer a comprehensive, broad analysis of the concept, based on political theories of four thinkers of paramount influence: Aristotle, Cicero, Machiavelli and Guicciardini.1 In the final part, the theories and eras of republican tradition will be compared based on the previous analysis, establishing their essential similarities and differences. Key words: Mixed Government, Classical Republicanism, Florentine Realism, Early Modern Republicanism, Aristotle, Cicero, Machiavelli, Guicciardini. Introduction The roots of republican political thought can be traced to the antiquity and the theories of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers. As might be expected in the two and a half millennia that followed, our understanding of republicanism has been subject to frequent and, sometimes, substantial change. Yet, one defining element has always remained: the concept embedded in its very name, derived from the Latin phrase res publica (public good, or, more broadly, commonwealth), its implicit meaning being that the government of a state is meant to be accessible and accountable to all citizens, its goals being the goals not merely of certain classes and factions, but of society as a whole. -

American Enlightenment & the Great Awakening

9/9/2019 American Enlightenment & the Great Awakening Explain how & why the movement of a variety of people & ideas across the Atlantic contributed to the development of American culture over time. (Topic 2.7) Enlightenment: Defining the Period 4 Fundamental Principles 1. Lawlike order of the natural world 2. Power of human reason 3. Natural rights of individuals 4. Progressive improvement of society • Natural laws applied to social, political and economic relationships • Could figure out natural laws if they employed reasoning: rationalism 1 9/9/2019 Most Influential • John Locke • Two Treatises of Government: gov’t is bound to follow “natural laws” based on the rights of that people have as humans; sovereignty resides with the people; people have the right to overthrown a government that fails to protect their rights. • Jean-Jacques Rousseau • The Social Contract: Argued that a government should be formed by the consent of the people, who then make their own laws. • Montesquieu • The Spirit of Laws: 3 types of political power – legislative, judicial & executive which each power separated into different branches to protect people’s liberties. Rationale for the American Revolution and the principles of the U.S. Constitution American Enlightenment Start Date/Event 1636: Roger Williams est. R.I. Separation of church & state Freedom of religion Rejects the divine right of kings & supports popular sovereignty 2 9/9/2019 Benjamin Franklin 1732: popularizes the Enlightenment with publication of his almanac Formed clubs for “mutual improvement” -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 8, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CITY OF SOUTHLAKE RANKED IN mother fell unconscious while on a shopping percent and helped save 1,026 lives. Blood TOP TEN trip. Bobby freed himself from the car seat and donors like Beth Groff truly give the gift of life. tried to help her. The young hero stayed calm, She has graciously donated 18 gallons of HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS showed an employee where his grandmother blood. OF TEXAS was, and gave valuable information to the po- John D. Amos II and Luis A. Perez were lice. While on his way to school, Mike two residents of Northwest Indiana who sac- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Spurlock came upon an accident scene. As- rificed their lives during Operation Iraqi Free- Tuesday, September 7, 2004 sisted by other heroic citizens, Mike broke out dom, and their deaths come as a difficult set- Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, it is my great one of the automobile’s windows and removed back to a community already shaken by the honor to recognize five communities within my the badly injured victim from the car. After the realities of war. These fallen soldiers will for- district for being acknowledged as among the incident, he continued on to school as usual to ever remain heroes in the eyes of this commu- ‘‘Top Ten Suburbs of the Dallas-Fort Worth take his final exam. nity, and this country. Area,’’ by D Magazine, a regional monthly The Red Cross is also recognizing the fol- I would like to also honor Trooper Scott A. -

Alexander the Great

RESOURCE GUIDE Booth Library Eastern Illinois University Alexander the Great A Selected List of Resources Booth Library has a large collection of learning resources to support the study of Alexander the Great by undergraduates, graduates and faculty. These materials are held in the reference collection, the main book holdings, the journal collection and the online full-text databases. Books and journal articles from other libraries may be obtained using interlibrary loan. This is a subject guide to selected works in this field that are held by the library. The citations on this list represent only a small portion of the available literature owned by Booth Library. Additional materials can be found by searching the EIU Online Catalog. To find books, browse the shelves in these call numbers for the following subject areas: DE1 to DE100 History of the Greco-Roman World DF10 to DF951 History of Greece DF10 to DF289 Ancient Greece DF232.5 to DF233.8 Macedonian Epoch. Age of Philip. 359-336 B.C. DF234 to DF234.9 Alexander the Great, 336-323 B.C. DF235 to DF238.9 Hellenistic Period, 323-146.B.C. REFERENCE SOURCES Cambridge Companion to the Hellenistic World ………………………………………. Ref DE86 .C35 2006 Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World ……………………………………………… Ref DF16 .S23 1995 Who’s Who in the Greek World ……………………………………………………….. Stacks DE7.H39 2000 PLEASE REFER TO COLLECTION LOCATION GUIDE FOR LOCATION OF ALL MATERIALS ALEXANDER THE GREAT Alexander and His Successors ………………………………………………... Stacks DF234 .A44 2009x Alexander and the Hellenistic World ………………………………………………… Stacks DE83 .W43 Alexander the Conqueror: The Epic Story of the Warrior King ……………….. -

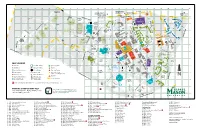

GMU-Fairfax-Campus-Map-2021.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z NO ENTRY NO EXIT EXIT NO Rapidan River Rd UNIVERSITY DRIVE TO: University Park Intramural Fields Mason Enterprise Center Commerce Building OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 TO: 4301 University Dr. 4087 University Dr. University Townhouse Complex 9 ROBERTS ROAD TO: 4260 Chain Bridge Rd. Tallwood 4210 Roberts Road R E V I KR C O N N A H A P P A 1 Student Townhouses 47 UNIVERSITY DRIVE UNIVERSITY DRIVE VE Reserved Parking GEORGE MASON BLVD S DR I PU M Field #1 LOT P A 35 C General Permit A Q 42 Parking U CO T S W OL I I D Rappahannock River A A S R H Parking Deck C C I 96 N L Spuhler Field L L LOT O R 38 L L D E 45 A A General Permit E 2 N O Mesocosm K R EVESHAM LANE E Parking Research BREDEN HILL LANE R L P ATRIOT CIRCLE Area A E PATRIOT CIRCLE N 39 V CHESAPEAKE RIVER LANE PERSHORE LANE I E R LOT M N Tennis CAMPUS DRIVE 23 97 Pilot A Softball General 63 62 Courts D House I Stadium Field House P Stadium Permit 98 D A Parking WEST CAMPUS WAY R LOT I Finley 61 3 Reserved Lot 69 OA Parking 34 S R 24 T Field #3 16 R Wotring 60 Courtyard 70 E OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 E B C A M P U S D R I V E L 56 C 65 STAFFORDSHIRE LANE R 20 I 71 51 49 RO C 21 BUFFALO CREEK CT T 58 72 4 O 33 Field #4 I 77 R 19 Maintenance T 64 WES T RAC A Storage Yard 6 Throwing CAMPUS DRIVE P 78 CA MPU S Fields Field 2 76 68 AY PA R K I N G 73 W LO T D 22 ROCKFISH CREEK LANE R 75 E Faculty/Staff Parking IV 74 R 53 66 8 57 SUB I NA Lot T N 5 5 31 E VA RIV 28 I CA US D AQUIA CREEK LANE R M P 67 Field #5 59 Y Kelly II A W NNA RI V E R 32 CAMPUS DRIVE A IV BRADDOCK ROAD/RT 620 PV LO T 10 R 27 KELLEY DRIVE General Parking 55 SHENANDOAH RIVER LANE 48 13 The Hub MASON POND DRVE 41 6 GLOBAL LANE RAC Mason Pond 25 Parking Deck BANISTER CREEK CT. -

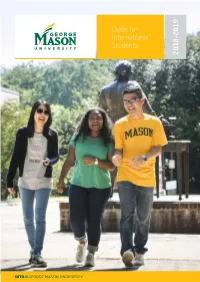

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University?

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University? Make World-Changing Discoveries Tier 1 #14 1st Research Institute 1 of 81 Public Universities with Washington, DC, ranks #1 Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 for the most STEM jobs in Highest Research Activity Most Innovative School a major US metro region (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education) (U.S. News & World Report 2017) (AIER College Destinations Index 2016) #22 #12 Safest Campus Most Diverse University in the US in the United States (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (National Council for Home Safety and Security 2017) Ranked #22 45 minutes Nationwide for Top Internship Opportunities Outside of Washington, DC (The Princeton Review 2016) Employability at George Mason University Mason graduates are employed by many top companies, including: 84% 76% Boeing Lockheed Martin of employed students of Mason students are Volkswagen Accenture are in positions related employed within six Freddie Mac Marriott International to their career goals months of graduation Ernst & Young IBM (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) 2 | INTO George Mason University 2018–2019 Top Programs GRADUATE #7 #17 #20 #27 Cybersecurity Special Education Criminology Systems Engineering (Ponemon Institute 2014) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) #33 #33 #64 #67 Economics Healthcare Public Policy Analysis Computer Science (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Management (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) UNIVERSITY* #68 #78 #110 #140 Top Public Best Undergraduate Best Undergraduate in National Schools Business Programs Engineering Programs Universities *U.S.