The Spirit of Democratic Socialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inhoudsopgave NIEUWSBRIEF 235 – 15.11.2015

Inhoudsopgave NIEUWSBRIEF 235 – 15.11.2015 Duitse scholen schrappen viering St-Maarten om moslimmigranten niet te kwetsen ....................................... 3 Veel immigranten hebben AIDS, syfilis, onbehandelde TBC” – gezondheidszorg in Duitsland op de knieën door asielchaos .................................................................................................................................................. 4 VN wil in 2030 verplicht biometrisch ID-bewijs voor ieder mens ....................................................................... 5 AfD politicus: ‘Duitsland op de rand van anarchie en een burgeroorlog’ .......................................................... 6 Staatsschuld stijgt met iedere immigrant bijna 80.000 euro .............................................................................. 7 Refugees not Welcome! Gedragen door het volk: De keiharde “vluchtelingen”politiek van Tsjechië ............... 8 Ook Nederlands Koningshuis gekaapt sinds 1940? .......................................................................................... 9 De Tweede Wereld Oorlog en haar geldmagnaten ......................................................................................... 22 Een zwarte dag voor Turkije ............................................................................................................................ 33 De waarheid over Gaddafi’s Libië .................................................................................................................... 35 Hillary Clinton ontmaskerd -

Rosary Hill Shooters to Clash With

VOL. 10, NO. 3 ROSARY HILL COLLEGE, BUFFALO, N. Y. MARCH 6, 1959 Dr. Bella Dodd, Ex-Communist, Lawyer To Speak on "Challenge To Americans" Few people in the United States today are more familiar with the objectives of the American Communist Party than Bella Dodd. Her knowledge is the result of first-hand experience, for Dr. Dodd was herself a member of the Communist Party for a number of years. Under the sponsorship of the Student Government Association, Dr. Dodd will speak at Rosary Hill on Sunday, March 8 at 8 :00 P. M. Her topic will be “Challenge to Americans.” Social .Problems Pose Dilemma After receiving her master’s degree from Teacher’s College Colgate Thirteen of Columbia University and her doctorate in law from New York Cheerleaders set for the conflict tonight: 1 to r. (front) To Offer Fest University, Bella Dodd was ad Katherine Collins, Kathleen Colquhoun. (back)) Patricia mitted to the New York State Bar Association in 1930. Four Heffernan, Carol Condon, Adele De Collibul Marsha THE COLGATE THIRTEEN, years prior to that she had be Randall and Molly Moore. known as “A m erica’s Unique come an instructor at Hunter Collegiate Singing Group,” will Uollege where she remained un sing at Rosary Hill on Friday til her resignation in 1938. Con Rosary H ill Shooters To Clash March 20. They will give their cern over social problems in concert in the Mafian Social Room at noon. this country and disgust with With Defending D YC Five the mediocrity of fellow Catho The Thirteen, formed in 1942 lics gradually drove Dr. -

Beggars on Horseback: Creating a Pan- African Power Paradigm for the 21St Century

Beggars On Horseback: Creating a Pan- African Power Paradigm for the 21st Century BEGGARS ON HORSEBACK CREATING A PAN AFRICAN POWER PARADIGM FOR THE 21ST CENTURY “Set a beggar on horseback and he’ll ride to the devil…”Tshiluba proverb FORWARD This is an Essay on Africa written on the eve of the 21st Century. Initially penned while the author was living in Africa as a cofounder of the Institute For the Development of Pan-African Policy, IDPAP, this essay was intended to serve as that NGO’s Geopolitical, and Economic Overview at the time. Though written in 1998-99, much of what now besets Africa, the AU, and African leaders have their roots in the Historical analysis presented here. Because of its length, “Beggars On Horseback” will be reproduced here in three parts, the last of which will address the current Western, U.S., and Chinese expropriation of Africa’s strategic minerals and resources under the Rubric of Globalization, and the “War on Islamic Extremism or “Terrorism.” DBW On the eve of the 21st century, Africa is up for sale at bargain basement prices. Many African states and Africa’s political leadership seem to engage in dead end diplomatic and economic activity because they perceive Africa as undeveloped rather than unorganized. African leaders have accepted the European concepts of power as hierarchical and external. Consequently, they have acquiesced to Eurocentric power paradigms, which marginalized Africa and wring their hands in despair while accepting the commandments of the IMP from on high. To some Africans desperate for hard currency and favorable foreign exchange selling Africa is just another game they play along with. -

F. Stone's Weekly

Should Communists Be Allowed to Teach? See Page 2. /. F. Stone's Weekly r. >rom'l mil.!, lie. VOL. I NUMBER 6 FEBRUARY 21, 1953 WASHINGTON, D. C 15 CENTS Anti-Zionism or Anti-Semitism? THE RUSSIANS FEAR WAR AND ARE SHUTTING the last win- at the crossroads of the world, where it can all too easily be dows on the West in preparation for it. That seems the most trampled by contending armies. It needs peace. It' cannot reasonable explanation for the anti-Zionist "show trials" which afford to fight the battles of the great Powers. For no nation have begun in the Soviet world. The Jews are the last people would a new war be a greater tragedy than for tiny Israel on in the U.S.S.R. and its satellites who still had some contact the edge of the petroleum fields which will be the first target with the West through such Jewish philanthropic organiza- of the air fleets. And no people needs peace more than the tions as the Joint Distribution Committee. Jews, a minority everywhere. In a long conflict, the Jews on Soviet policy never went beyond cultural autonomy; cen- the Soviet side will be suspected of pro-Westernism and on the tripetal nationalist tendencies are as much feared as in the days anti-Soviet side of pro-Communism. of the Czars. Nationalism (except at times for Russians) is officially stigmatized as "bourgeois," though the constant at- NONE OF us KNOW WHAT is REALLY HAPPENING IN EAST- tacks on "Titoism" in the satellites show how strongly it sur- ERN EUROPE. -

Method Behind the Madness

Method Behind the Madness 6/ t"!" t hash..! heenbeen sad,"sad " writes Soviet "I believe in truth and the power of in 1947 and attributed tto 'X.'" It is a ideas to convey the truth," says Go suggestion he made again the following I defector Anatoliy Golitsyn in year in his lengthy analysis memoran M the foreword to his new book, litsyn, and he expresses the hope that his I "wtTto bookwillhelp the people of theWestto dum of March 1989. The PerestroikaDeception, "to observe To those familiar with Foreign Af the jubilation of American and West see the dangers before them "and to re fairs, it is not surprising that the defec European conservatives who have been cover from their blindness." If it is within the power of a book to do that, tor's innocent request went unrequited. cheering 'perestroika' without realizing As the flagship journal of the wodd- that it is intended to bring about their then there is certainly none better than govemment-promoting Council on For own political and physical demise. Lib his for that daunting task. eign Relations (CFR), it has been the eral support for 'perestroika' is under No one better apprehends or more clearly explains the dialectic, the plan leading promoter of perestroika, glas- standable, but conservative support nost, and convergence in the West for cameas a surprise to me." ning framework, and the operational methods of the Communist deception decades. Time magazine hascalled For For one who studied and worked strategy than Golitsyn. We emphasize eign Affairs "the most influential peri within the inner sanctum of Soviet in odical in print." Unformnately, Aat is telligence and who risked his life to Communist because there apparently is a vital dimension of the deception strat- an apt description. -

Wikileaks & Assange Exposed Deep State Crimes • Christian And

WikiLeaks & Assange Exposed Deep State Crimes • Christian and Conservative Comeback May 20, 2019 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH FREEDOM’S VOICES RESCUING OUR CHILDREN SUMMER TOUR 2019 WITH ALEX NEWMAN There is a reason the Deep State globalists sound so confident about the success of their agenda — they have a secret weapon: More than 85 percent of American children are being indoctrinated by radicalized government schools. In this explosive talk, Alex Newman exposes the insanity that has taken over the public school system. From the sexualization of children and the reshaping of values to deliberate dumbing down, Alex shows how dangerous this threat is — not just to our children, but also to the future of faith, family, and freedom — and what every American can do about it. GEORGIA SOUTH DAKOTA May 17 / Suwanee / Dahlys Hamilton / 770-870-9401 June 28 / Rapid City / Tonchi Weaver / 605-390-4078 May 17 / Marietta / Boyd Parks / 770-975-3303 WYOMING SOUTH CAROLINA June 29 / Sheridan / Jan Loftus / 307-673-0157 May 20 / Spartanburg / Evan Mulch / 804-804-0789 June 30 / Casper / Marti Halverson / 307-413-5236 May 21 / Greenville / Evan Mulch / 864-804-0789 July 1 / Cody / Marti Halverson / 307-413-5236 May 21 / Greenville / Justin Summerlin / 864-230-2496 OREGON May 22 / Columbia / Ray Moore / 803-237-8680 July 10 / King City/ Sally Crino / 503-522-3926 May 23 / Spartanburg / Evan Mulch / 864-804-0789 May 24 / Summerville / Joan Brown / 843-810-9670 WASHINGTON July 12 & 13 / Spokane / Caleb Collier / 509-999-0479 -

Ford Settles for Semi-Annual Jobless Benefits

Mass Pressure Needed on School Jim Crow <•> NAACP Plans New Moves in Southern Courts t h e PUBLISHEDMILITANT ‘WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE By George Lavan The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People held a meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, June 5 Vol. XIX — No. 24 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, JUNE 13, 1955 PRICE: 10 Cents to plan its strategy in the fight to desegregate Southern schools. The conference was at tended by 55 delegates from 16 without this reaffirmation many Southern and border states. It people might think the court had was decided that legal actions .ndeed reversed its original de- would be started against school jision. Point 2 is but a corollary boards which had not made plans of Point 1. I f school segregation to begin applying the Supreme is unconstitutional then laws Court decision by the opening providing fo r such segregation Ford Settles for Semi-Annual of school next September, cannot also be constitutional. In the meantime NAACP Point 3 is small consolation. branches were urged to put the Fine sounding words like “good heat on local school boards by faith,” “ reasonable,” “ prompt,” petitioning them to begin com “ as soon as practicable,” etc., are plying with the high court’s rul the sugar coating for the bitter ing. The day before the con fact that the court’s ruling is Jobless Benefits Supplement ference nine Negro parents in almost impotent. Atlanta filed such a petition These words were put in to with the Atlanta school board. placate the enemies of segrega ted schools and to cover the “PERHAPS A CENTURY” hypocrisy of the court which Referring to a statement by ruled a year ago that segrega Open Letter to Foster Workers Hit the Attorney General of Georgia tion was unconstitutional and that the Supreme Court’s de which has now ruled, in effect, cision meant “ perhaps a century that it can continue in the Concessions of litigation,” Thurgood Mar South indefinitely. -

Searchable PDF Format

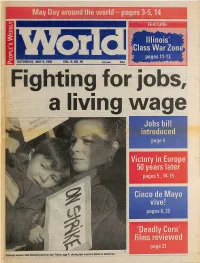

May Day around the world - pages 3-5,14 FEATURE: SATURDAY, MAY 6,1995 VOL.9, NO.48 Fighting for jobs, a living wage Jobs bill introduced page 4 Victory in Europe s 50 years later pages 5,14-15 Cinco de Mayo vive! pages 6,22 'Deadly Corn' films reviewed page 21 Safeway worker Gaif Zacarias and her son Travis, age 4, during last month's strike in California. 2 People's Weekly World Saturday, May 6.1995 May Day salute in die 'class \ . We, ourselves workers and unioii members, would return our nation to the "good old days" of salute our sisters and brothers in Decatur, Illinois no unions,low wages and no benefits, no to elect now engaged in life-and-death struggles with ed officials who side with capital against labor. three of the world's largest multinational corpo We honor these shock troops of the working rations. Seldom have the class lines been drawn class - auto workers on strike against CaterpiDar; more sharply, seldom have the stakes been high rubber workers on strike against Bridgestone/- er; seldom has the battle been waged with more Firestone, paper workers locked out by A.E. Sta- determination. ley - and are mindful of our responsibility as We,like our sisters and brothers in the heart of well. We pledge our best efforts to guarantee that the Illinois "Class War Zone," say no to scabs and the struggles in Decatur - as well as those of tmion busting, no to arrogant corporations who workers everywhere - will end in victory. Jeny Acosta, Utility Workers, more, Md• Kevin Doyle, Local Joseph Henderson, USWA Chicago, II • Loimie Nelson, -

The Fight of 1950S Women Against Communism and the Rise of Conservatism by Lori May

Housewives With A Mission: The Fight of 1950s Women Against Communism and the Rise of Conservatism By Lori May Photo of the Cleaver family from the television program Leave it to Beaver. From left: Hugh Beaumont (Ward), Tony Dow (Wally), Barbara Billingsley (June), Jerry Mathers (Theodore AKA "Beaver"). 8 January 1960. ABC Television. Television shows such as, Leave it to Beaver, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet and Father Knows Best, filled the airwaves, and magazines such as McCalls and Good Housekeeping lined the news stands with pictures of the American way of life in the 1950s. A suburban, middle class life where families lived in a furnished and newly equipped modern home, complete with car, two children and a dog. Where father went to work and mother stayed at home baking and taking care of the family and left the cares of the world to her husband.[1] However, alongside this picture of an ideal America, the media presented the Red Scare, and the threat of communist infiltration that would destroy this American way of life. A considerable portion of white, educated, middle-class housewives and mothers content in their role as wives and mothers embraced the prevailing Red Scare and its rhetoric of anti- Communism and the cult of motherhood, which promoted mothers as defenders of morality and the American way of life against the threat of communism. As a result they established grassroots activities within their children’s schools, and communities and exercised a conservative political voice that would ultimately shift the Republican Party from a democratic moderate party to a more fundamentally conservative right wing party that nominated Barry Goldwater for president in 1964 and placed Ronald Reagan as governor of California in 1966, thus making conservatism mainstream.[2] The activism of middle class, suburban housewives after WWII in their role as mothers was not a new phenomenon. -

Vito Marcantonio Part 5 of 25

- L_=. 92_YI_ Q-I --4 4-._ __ ~.- L __. V ,. __ ;, .,. -- --UL. ._~1--.._ Iv _| v- ~.¢~v-1_ ,.~.--.,.~,,,,,...,_....<-.... -___,~4-. ..',._ 92 FEDERAL BUREAU OP INVESTIGATION VITO MARCANTONIO PART 3 OF 12 FILE NUMBER 2 100-28126. __ -92 '| f % *1m,/ MEMO: NY100-53854 1 State Headquarters, conferred with ALEX believed to be ALEX%ROSB, State Secretary of the American Labor Party!, and, among other things, asked "BID" ts tell MARK probably V.M.! tn "stop bmihering us with the second front pnopositien", to which "BID" replied that if ALEX doesn't step harping on the third frent "then there will be no second Qr third Rt" 0 " E0£53 24, -2 2 5:Re p wt ofVCo ~ni r dentisl - MMI brmant1 L $%%f d@ted July 22, l9£2, ccording be ibis report, V.H. addressed a min the War Rally sponsored by the Greater New York Industrial Union Council at Madison quare Park, New York City, where flags of the Soviet Union were displayed in large numbers. V.H¢, in his talk, blamed the appeasing fsrves in cur government for lack af military sation in opening a second fft-0 1G0-26699-65: Rspurt of confidential Informant ND119 dated July 22, 1942, re: a meeting sf the &reat%r NewYbrk Industrial auncil, C.I.O, at adison Square Park on the same date. This confidential in- formant advised that the majority of the speakers were non-Comunists and that V.M. was one of the several speakers. Gther speakers listed in this report were: JOSEPHGURRAN, presidegt of the above mentionedMorgan- ization; BEN GOLD, head of the Furriers Qnion and wha has been n Smr muniat Party mengber for the last ten years; IRVING POTASH,head of the furriers Joint °ouncil in New Yorkand alleged Communist Partymember far the past 8 years. -

The Impact of Cold War Events on Curriculum and Policies, and the Protection of Children in Postwar Ontario Education, 1948-1963

THE IMPACT OF COLD WAR EVENTS ON CURRICULUM AND POLICIES, AND THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN IN POSTWAR ONTARIO EDUCATION, 1948-1963 FRANK K. CLARKE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO July 2020 © Frank K. Clarke, 2020 ii Abstract Between 1948 and 1963 Ontario educators and policy makers, at the school boards and within the Department of Education, confronted the challenge of how to educate students for a divided and dangerous Cold War world. That the Cold War was not a distant or esoteric phenomenon became apparent when the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb in 1949. In addition, local Communist Party members, particularly within Toronto, actively sought to recruit students to their ranks. As a result, the protection of children, both physically and ideologically, became a paramount concern: physically through civil defence drills within schools to protect against nuclear attack and ideologically against anti-capitalist and atheist Communism through citizenship education that reinforced a conservative form of democratic citizenship, including the nuclear family, civic rights and responsibilities, Protestant Christianity, a consumer capitalist society, and acceptance of the anti-Communist Cold War consensus under the auspices of the United Nations and NATO. The Cold War paradigm, however, began to shift starting with the implosion of the Labour Progressive (Communist) Party in 1956 following the revelations of Stalin’s crimes. Thereafter, the Communist threat shifted from domestic Communists to fear of a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. -

The Politician

Foreword to 2002 Edition of The Politician The History of The Politician In December, 1954, I wrote a long letter to a friend, in which I expressed very severe opinions concerning the purposes of some of the top men in Washington. — Robert Welch, The John Birch Society Bulletin, August 1960 Those who remember personally the founder of The John Birch Society and his tendency towards verbal thoroughness will appreciate the understatement in his reference to “a long letter to a friend.” Though he could be brief when brevity was called for, Robert Welch did not place limits on expanding his thoughts to whatever degree he deemed necessary to prove his case. In the days before e-mail and other high-speed electronic communications, letter writing was a prime means of sharing ideas. Few had mastered the art like Robert Welch, and he frequently used that ability to maximum advantage. His position as a leader in the business community — serving seven years as a member of the board of directors of the National Association of Manufacturers and two and one-half years as the chairman of NAM’s Education Committee — afforded him a natural forum for the exchange of ideas concerning the state of our nation. As his circle of personal acquaintances expanded, Mr. Welch became a close confidant of and campaigner for Robert Taft during the senator’s 1952 presidential campaign. He met personally with such world leaders as President Syngman Rhee of Korea, President Chiang Kai-shek of China, and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of Germany. Gregarious by nature, Robert Welch could be a witty conversationalist.