Four Quarters: January 1971 Vol. XX, No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

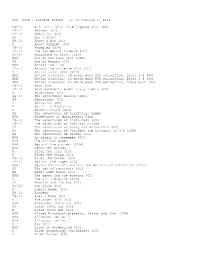

POPULAR DVD TITLES – As of JULY 2014

POPULAR DVD TITLES – as of JULY 2014 POPULAR TITLES PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) PG-13 After Earth (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent -

MONTHLY GUIDE JANUARY 2015 | ISSUE 66 | Pacific

MONTHLY GUIDE JANUARY 2015 | ISSUE 66 | PACIFIC BRITISH MONTH CAMERAMAN: THE LIFE AND WORK OF JACK CARDIFF, ONE DIRECTION , RUBY BLUE, ROUTE 94, AND MORE... EUROCHANNEL GUIDE | JANUARY 2015 | 1 2 | EUROCHANNEL GUIDE | JANUARY 2015 | MONTHLY GUIDE| JANUARY 2015 | ISSUE 66 BRITISH British Month MONTH as the curtain closed on a 2014 packed with delightful surprises, emotionally stirring stories and stunning landscapes, we’re proud to welcome you to a new year of audiovisual marvel. In 2015, Eurochannel will continue showcasing the creative, colorful, and Mariza and the unique in European culture that we admire. Story of Fado The year kicks off with a month dedicated to cinematic ventures made in Britain. In January we present British Month, a compilation of dramas, comedies, documentaries and music. We will enjoy the stunning acting of Academy Award nominee and BAFTA Award Winner Bob Hoskins, Emmy Award-winner Brenda Blethyn, French film legend Josiane Balasko, among others. The stories of Eurochannel’s British Month will tackle in a very moving, One Direction yet entertaining way, sensitive issues such as pedophilia, immigration, religion and poverty. Table of contents In January we will also enjoy the stories of real-life people with two documentaries. The first offers a familiar view on a legend of British 4 British Month cinema, Jack Cardiff, in an intimate portrait. The second treats us to 28 Week 1 the great Portuguese tunes and an enchanting account of the history of fado. Be sure not to miss them! 30 Week 2 32 Week 3 What would a new year be without new music artists? January is no 34 Week 4 exception. -

Chris & Martin's Movies Seen

Chris & Martin’s Movies Seen Date movie Actors Rating (bad 1 2 3 4 5 good) 10 Items or less 8/17/2015 A Single Man American Beauty 5/23/2020 “10” Ten A Star Is Born Barbra 5/5/2018 American Graffiti 4/19/2014 12 Years A Slave 2/24/2019 A Star Is Born Bradley Gaga 3/24/2014 American Hustle 3/16/2014 20 Feet From Stardom 6/21/2010 A Star Is Born w Judy Garland 5/22/2017 American Mustang 2001 A Space Odessey 2/11/2012 A Summer in Genoa 6/8/2015 American Sniper 2012 12/11/2015 A Very Murray Christmas (:-( 7/8/2015 Amy (Winehouse) 10/5/2014 3 Days to Kill 020521 M exer 5/20/2016 A Walk In the Woods 4/29/2012 An Ideal Husband 3 to Tango 5/20/2016 A Walk In the Woods An Officer and a Gentlman 6/3/2011 30 Seconds Over Tokyo About A Boy 5/19/2015 And So It Goes 1/6/2011 $5 A Day 6/21/2020 Absence of Malice 6/1/2015 And the Oscar Goes To 8/9/2015 5 Flights Up 7/9/2010 Accidental Husband Angel Eyes 50 1st dates 8/4/2021 Acts Of Vengence Banderas Exercise 4/21/2020 Angel Has Fallen 11/15/2010 500 Days of Summer 11/5/2013 Admission 7/15/2011 Angela Landbury bio 11/25/2010 6th Sense 3/25/2020 Aeronuts 11/29/2010 Angelina Jolie 12/26/2020 7500 3/4/2012 Air Force 7/18/2013 Anna Katerina 8 1/2 Air Force One Martin Annie Hall 3/13/2011 9 Months Airplane! Apocalypse Now 12/22/2011 A Christmas Carol (1938) & Alien Apollo 13 7/2/2016 A Country Called Home 9/29/2011 All About Steve Sandra 12/27/2012 Arbitrage Richard 9/1/2019 A Dog’s Journey 5/4/2014 All Is Lost 3/3/2013 Argo 9/2/2019 A Dog’s Purpose 7/21/2016 All Roads Lead to Rome 10/9/2011 Around the Bend -

Popular DVD Titles - As of July 2017

Popular DVD Titles - as of July 2017 PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) R Absolutely fabulous, the movie (CC) (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 Accidental love (SDH) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) R The accountant (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The Addams family (CC) PG=13 The Addams family values (CC) R The Adderall diaries (SDH) NRA Addiction: A 60’s love story (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA The affair: Season one (4v) (CC) Popular DVD Titles - as of July 2017 NRA The affair: Season two (5v) (SDH) NRA An -

West Islip Public Library

DVD LIST - POPULAR TITLES – as of January 1, 2013 PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About Schmidt (CC) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Pluto Nash (CC) PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent Cody Banks (CC) NRA The agony and the ecstasy (CC) R The air I breathe (SDH) PG Akeelah and the bee (CC) PG-13 The Alamo (CC) R Albert Nobbs (CC) PG-13 Alchemy -

The Worlds of Langston Hughes

The Worlds of Langston Hughes The Worlds of Langston Hughes Modernism and Translation in the Americas VERA M. KUTZINSKI CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Ithaca & London Copyright © 2012 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2012 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kutzinski, Vera M., 1956– The worlds of Langston Hughes : modernism and translation in the Americas / Vera M. Kutzinski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5115-7 (cloth : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-8014-7826-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Hughes, Langston, 1902–1967—Translations—History and criticism. 2. Hughes, Langston, 1902–1967—Appreciation. 3. Modernism (Literature)—America. I. Title. PS3515.U274Z6675 2013 811'.52—dc23 2012009952 Lines from “Kids in the Park,” “Cross,” “I, Too,” “Our Land,” “Florida Road Workers,” “Militant,” “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” “Laughers,” “Ma Man,” “Desire,” “Always the Same,” “Letter to the Academy,” “A New Song,” “Birth,” “Caribbean Sunset,” “Hey!,” “Afraid,” “Final Curve,” “Poet to Patron,” “Ballads of Lenin," “Lenin,” “Union,” “History,” “Cubes,” “Scottsboro,” “One More S in the U.S.A.,” and “Let America Be America Again” from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright © 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. -

Shadow S in the Sun Gayathri Ramprasad

Advance Uncorrected Proofs/Not for Resale/Available March 2014 As a young girl in Bangalore, Gayathri was surrounded by the fragrance of jasmine and Ramprasad in the Sun Gayathri Shadows flickering oil lamps, her family protected by Hindu gods and goddesses. But as she grew older, demons came forth from the dark corners of her fairytale-like kingdom—with the scariest creatures lurking within her. The daughter of a respected Brahmin family, Gayathri began to feel different. “I can hardly eat, sleep, or think straight. The only thing I can do is cry unending tears.” Her parents insisted it was all in her head. Because traditional Hindu culture has no concept of depression, no doctor could diagnose and no medicine could heal her mysterious illness. This beautifully written memoir traces Gayathri’s courageous thirty-year battle with the depression that consumed her from adolescence through marriage and a move to the United States. It was only after the birth of her first child, when her husband discovered her in the backyard “clawing the earth furiously with my bare hands, intent on digging a grave so that I could bury myself alive,” that she finally got the help she needed. After a stay in a psych ward she eventually found “the light within,” an emotional and spiritual awakening from the darkness of her tortured mind. Gayathri’s inspiring story provides a first-of-its-kind cross-cultural lens to mental illness—the very different way it is (or is not) regarded in India and in America, and the way she drew on both her rich Hindu heritage and Western medicine to find healing. -

Checkout Library: ABORO-HIGH Top Circulating Titles This Year2

Checkout Library: Top Circulating Titles this ABORO-HIGH Year2 Checkouts Title 75 The longest yard 66 Rain Man 65 Game of Thrones. 1/1 Checkout Library: Top Circulating Titles this ABORO-MAIN Year2 Checkouts Title Museum of Fine Arts (Boston) -- 899 Attleboro 244 Passengers The day the Earth stood still 206 Winter's bone 202 Copout 191 The hurt locker 190 Grown ups 189 Jonah Hex 187 Funny people 182 I am number four 181 Inglourious Basterds 177 Season of the witch Dragon hunters 175 The wolfman 173 The tourist 169 Sweeney Todd. 168 The Oxford murders 165 Barbie as the Island Princess 162 My Cousin Vinny Eat Pray Love 161 My sister's keeper 160 The other man 159 Priest 158 Avatar Barbie. 156 Contagion Enchanted 155 The Prisoner 154 Annie Agora 153 Black swan To save a life 152 Scooby-Doo! 151 2012 supernova 150 Diary of a wimpy kid dog days / 149 Shutter Island 148 Fantastic Mr. Fox Ondine 147 The help Alex Cross 146 Surrogates The boy in the striped pajamas Act of vengeance 145 Arbitrage Up Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 144 The unborn The girl who played with fire Flickan 143 som lekte med elden / The men who stare at goats 142 Apollo 18 1/53 Checkout Library: Top Circulating Titles this ABORO-MAIN Year2 Checkouts Title Madea's big happy family Mary Poppins Meeting evil 142 Rampart The chronicles of Narnia. The librarian. 140 Letters to Juliet Harry Potter and the Order of the 139 Phoenix Santeria : the soul possessed / Indiana Jones and the kingdom of the crystal skull 138 The Bourne legacy The Green Hornet IronMan : armored adventures. -

Shadows in the Sun: the Experiences of Sibling Bereavement in Childhood Series in Death, Dying, and Bereavement Robert A

SHADOWS IN THE SUN: THE EXPERIENCES OF SIBLING BEREAVEMENT IN CHILDHOOD SERIES IN DEATH, DYING, AND BEREAVEMENT ROBERT A. NEIMEYER, CONSULTING EDITOR Davies— Shadows in the Sun: The Experiences of Sibling Bereavement in Childhood FORMERLY SERIES IN DEATH EDUCATION, AGING, AND HEALTH CARE HANNELORE WASS, CONSULTING EDITOR ADVISORY BOARD Herman Feifel, Ph.D. Jeanne Quint Benoliel, R.N., Ph.D. Balfour Mount, M.D. Bard—Medical Ethics in Practice Benoliel—Death Education for the Health Professional Bertman— Facing Death: Images, Insights, and Interventions Brammer—How to Cope with Life Transitions: The Challenge of Personal Change Cleiren— Bereavement and Adaptation: A Comparative Study of the Aftermath of Death Corless, Pittman-Lindeman—AIDS: Principles, Practices, and Politics, Abridged Edition Corless, Pittman-Lindeman—AIDS: Principles, Practices, and Politics, Reference Edition Curran—Adolescent Suicidal Behavior Davidson— The Hospice: Development and Administration, Second Edition Davidson, Linnolla— Risk Factors in Youth Suicide Degner, Beaton— Life-Death Decisions in Health Care Doka—AIDS, Fear, and Society: Challenging the Dreaded Disease Doty— Communication and Assertion Skills for Older Persons Epting, Neimeyer—Personal Meanings of Death: Applications of Personal Construct Theory to Clinical Practice Haber— Health Care for an Aging Society: Cost-Conscious Community Care and Self-Care Approaches Hughes—Bereavement and Support: Healing in a Group Environment Irish, Lundquist, Nelsen— Ethnic Variations in Dying, Death, and Grief: Diversity -

FT0507 MOV WEB.Indd

MAY 2007 A-Z MOVIES A ALL THIS, AND HEAVEN ANNIE O B solders is assigned a do-or-die Walter Pidgeon, Gilles Payant. TOO HALLMARK CHANNEL 1996 mission during WWII. A heart-wrenching tale of a boy ACROSS THE PACIFIC TCM 1940 Romance (PG) 0 Drama (PG) B.R.A.T. PATROL, THE who becomes attached to the dog BATMAN of his employer. TCM 1942 War 0 May 8, 9 May 14, 15, 16 MOVIE GREATS 1986 Family MOVIE GREATS 1989 Action (PG) May 11, 12 Charles Boyer, Bette Davis. A Coco Yares, Rob Stewart. May 1, 2, 11, 20 May 9, 10, 19, 31 BILOXI BLUES Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor. A period drama tracing the upstairs- A young girl makes the all-boy’s Sean Astin, Tim Thomerson. Michael Keaton, Jack Nicholson. SHOWTIME GREATS 1988 Comedy US agent tries to keep Axis spies downstairs affair between a duke high school basketball team. A group of misfits overhear a plot Batman’s long-time nemesis (M va) 0 to steal government equipment from blowing up the Panama Canal. and his governess. ANTHONY ZIMMER the Joker has sinister plans for May 11, 12, 16, 29, 30 and take it upon themselves to stop Gotham. Matthew Broderick, Christopher ACT OF VIOLENCE ALOHA, SCOOBY-DOO! WORLD MOVIES 2005 France the baddies. TCM 1948 Drama (PG) 0 MOVIE ONE 2005 Animation (PG) Romance Thriller (M av) Walken. A young man is sent to BATMAN & ROBIN basic training during WWII where May 18, 19 May 2, 26 May 25, 26 BABE: PIG IN THE CITY MOVIE EXTRA 1997 Action (PG) Van Heflin, Janet Leigh. -

Illinois Magazine

CP Jfr' !&( %%' IP Y* fc «r< ttr' •/^. 7 im^wsi^^^s^&m > * #T V^Wmw: ** Jl^/a^rsa jA."V~ ^K.-r»AHf >-r>uni-.^..^., .. Fee lor Library Materia.*. The Minimum NOTtce: Return or renew all each Lost Book is $50.00. responsible for person charging this material is The w.thdrawn from wh.ch it was its refurn to the library Date stamped below. on or before the Latest for d.scph- of books are reasons mutilation, and underlining Theft, Univer,*,. in a—Mrom the Tr, action and ma, result Center. 333-8400 To renew call Telephone AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN nunTFRSfTY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANACHAMPAIGN MAR 1 1 197S FEB 2 5 197* * I 8 1)91 L161— O-1096 i m This nut^ixm^h^. ' T h ( / / / i a " i 8 1/ </ .'/ a : i a \ r ~>v APOLLO Confectionery OUR MALTED MILKS ARE AX ASSET OF HEALTH Mouyios Bros. URBANA f i The I 1 1 i n a s M a g a sine •\ AFTER THE GAME Visit The Wright Sweet Shop "The right place for sweets" How refreshing a cool drink is after a close game! You will find our Bostons an agreeable sur- prise, our Malteds a revela- tion, and our candies of uniform excellence. -

Anthropology in the Public Arena Anthropology in the Public Arena Historical and Contemporary Contexts

Anthropology in the Public Arena Anthropology in the Public Arena Historical and Contemporary Contexts Jeremy MacClancy A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2013 © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing. Registered Offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offi ces 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Jeremy MacClancy to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.