Hitler and Picasso - Searching for 'The Degenerate'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18)

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18) São Paulo, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Apr 25–27, 2018 Deadline: Mar 9, 2018 Erika Zerwes In 1937 the German government, led by Adolf Hitler, opened a large exhibition of modern art with about 650 works confiscated from the country's leading public museums entitled Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst). Marc Chagall, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian and Lasar Segall were among the 112 artists who had works selected for the show. Conceived to be easily assimilated by the general public, the exhibition pre- sented a highly negative and biased interpretation of modern art. The Degenerate Art show had a rather large impact in Brazil. There have been persecutions to modern artists accused of degeneration, as well as expressions of support and commitment in the struggle against totalitarian regimes. An example of this second case was the exhibition Arte condenada pelo III Reich (Art condemned by the Third Reich), held at the Askanasy Gallery (Rio de Janeiro, 1945). The event sought to get support from the local public against Nazi-fascism and to make modern art stand as a synonym of freedom of expression. In the 80th anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in partnership with the Lasar Segall Museum, holds the International Seminar “Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil”. The objective is to reflect on the repercus- sions of the exhibition Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) in Brazil and on the persecution of mod- ern art in the country in the first half of the 20th century. -

4C the Anti-Modernists

seum, were some six hundred and fifty the art world of the twenty thousand works that the Nazis eventually confiscated from Ger- man institutions and collections. Many The anti-MOdERNisTs were subsequently burned; others were sold abroad, for hard currency. Wall texts Why the Third Reich targeted artists. noted the prices that public museums had paid for the works with “the taxes of the BY PETER sCHjEldAHl German working people,” and derided the art as mentally and morally diseased or as a “revelation of the Jewish racial soul.” Only a handful of the artists were Jews, but that made scant difference to a regime that could detect Semitic conta- gion anywhere. Some months earlier, Jo- seph Goebbels, the propaganda minister, had announced a ban on art criticism, as “a legacy of the Jewish influence.” “Degenerate Art” was a blockbuster, far outdrawing a show that had opened the day before, a short walk away, in a new edifice, dear to Hitler, called the House of German Art. “The Great German Art Exhibition” had been planned to demonstrate a triumphant new spirit in the nation’s high culture, but the preponderance of academic hackery in the work produced for it came as a rankling disappointment to Hitler, whose taste was blinkered but not blind. By official count, more than two million visitors thronged “Degen- erate Art” during its four-month run in Munich. Little is recorded of what they thought, but the American critic A. I. Philpot remarked, in the Boston Globe, that “there are probably plenty of people—art lovers—in Boston who will side with Hitler in this particular purge.” Germany had no monopoly on ou might not expect much drama the works. -

Modern Art and Politics in Prewar Germany

Stephanie Barron, “Modern Art and Politics in Prewar Germany,” in Barron (ed.), Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991): 9-23. In 1937 the National Socialists staged the most virulent attack ever mounted against modern art with the opening on July 19 in Munich of the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate art) exhibition, in which were brought together more than 650 important paintings, sculptures, prints, and books that had until a few weeks earlier been in the possession of thirty-two German public museum collections. The works were assembled for the purpose of clarifying for the German public by defamation and derision exactly what type of modern art was unacceptable to the Reich, and thus “un-German.” During the four months Entartete Kunst was on view in Munich it attracted more than two million visitors, over the next three years it traveled throughout Germany and Austria and was seen by nearly one million more On most days twenty thousand visitors passed through the exhibition, which was free of charge; records state that on one SundayAugust 2, 1937-thirty- six thousand people saw it.1 The popularity of Entartete Kunst has never been matched by any other exhibition of modern art. According to newspaper accounts, five times as many people visited Entartete Kunst as saw the Grosse Deutsche Kunstaussiellung (Great German art exhibition), an equally large presentation of Nazi-approved art that had opened on the preceding day to inaugurate Munich's Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German art), the first official building erected by the National Socialists. -

Gurlitt: Status Report «Degenerate Art» – Confiscated and Sold

Press Documentation Gurlitt: Status Report «Degenerate Art» – confiscated and sold November 2, 2017, to March 4, 2018 GURLITT: STATUS REPORT «Degenerate Art» – confiscated and sold November 2, 2017, to March 4, 2018 Table of contents 1. General information ...................................................................... 2 2. The exhibition .............................................................................. 3 3. Chronology of the Gurlitt Art Trove .................................................. 5 4. Short Biographies of the Members of the Advisory Board .................... 7 5. Accompanying volume published for the exhibition ............................ 9 6. Supporting program of the exhibition............................................. 10 Contact Maria-Teresa Cano, Head of Communication and Public Relations, Kunstmuseum Bern – Zentrum Paul Klee [email protected] 1/11 Press Documentation Gurlitt: Status Report «Degenerate Art» – confiscated and sold November 2, 2017, to March 4, 2018 1. General information Duration of the exhibition 02.11.2017 – 04.03.2018 Team of curators Dr. Nina Zimmer, Director Kunstmuseum Bern – Zentrum Paul Klee Dr. Matthias Frehner, Director of Collections Kunstmuseum Bern – Zentrum Paul Klee Dr. Nikola Doll, Head of Provenance Research Kunstmuseum Bern Prof. (em.) Dr. Georg Kreis, Historian, Universität Basel Simultaneously at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn Gurlitt: Status Report. Nazi Art Theft and its Consequences November 3, 2017 – March 11, 2018 The patrons of the exhibition are -

“Degenerate” Art in Nazi Germany in 1937

Bates 1 Evan Bates 6 December 2019 Everything is Curated: Effective Control of “Degenerate” Art in Nazi Germany In 1937, the Nazi party headed by Adolf Hitler collected all of the artwork deemed to be against their worldview from all of the galleries in Germany at the time. Expressionism, Surrealism and Dada, movements targeting emotion or abstraction as opposed to precise form, were most targeted in the collection of over 650 works. The exhibition that held these artworks, “Entartete Kunst,” or “Degenerate Art” in English, was held in Munich and across the street from the grand pillared white building holding the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung,” or “Great German Art Exhibition,” showcasing works that the Nazis found ideologically or artistically valuable. Both were curated by Hitler’s favorite artist at the time: Adolf Ziegler and the “Great German Art Exhibition” did happen to include many of his works. The “Great German Art Exhibition” was, unfortunately for the Nazi party, much less successful than its counterpart as 3 million visitors participated in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition, more than three times that of the “Great German Art Exhibition.” While it may initially seem to be an unwise decision to place all of the works that could potentially harm their ideology in one place, the Nazis were able to strip the art of its potential power and convince the people of its degeneracy. In carefully understanding and manipulating the audience before and during the “Entartete Kunst” exhibition, the Nazi Party effectively silences the potential voice of the works of this “degenerate art,” because without doing so the ideas could have toppled their power. -

A War of Aesthetics – and Life and Death by Lance Esplund Mar

A War of Aesthetics – and Life and Death By Lance Esplund Mar. 20, 2014 New York Paul Klee's small, poignant gouache-on-paper "Masked Red Jew" (1933) is a childlike, abstract portrait that also serves as monument and oracle. It is part of the Neue Galerie's informative and affecting exhibition "Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937." Klee's title refers to the Red Jews, a fabled nation appearing in medieval German texts, who were prophesied to invade Europe and threaten Christendom, events leading to the end of the world. Painted the same year that Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Klee's stippled picture resembles an executioner's wall inscribed with a scrawled stick-figure, whose bowed head appears to be impaled on a cross. A yarmulke hovers like a bruised halo. And a large, looping X -- as if branded, marching -- flattens as it tramples the portrait. "Masked Red Jew" is not the most prominent work among the show's approximately 80 paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures, as well as films and several books, posters, photographs and photomurals -- two of which juxtapose aerial views of Dresden, before and after it was destroyed by Allied bombs. (The devastated side is the backdrop for "The Life of Christ," a moving suite of woodblock prints by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.) And Klee's "Red Jew" must compete here with other masterpieces by Klee, including the paintings "Mystical Ceramic (in the Manner of a Still-Life)" (1925) and "Gay Repast/Colorful Meal" (1928). Yet Klee's "Jew," like every artwork here -- from Oskar Kokoschka's brushy and stalwart oil painting "Self-Portrait as a Degenerate Artist" (1937) to Ewald Matare's beautiful little sleek bronze sculpture "Lurking Cat" (1928) -- has a story to tell. -

Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst), According to Hitler the Lucerne Auction, 1939 Picasso, Chagall, Ensor, Kokoschka, Corinth, Derain, Etc

Entartete Kunst, according to Hitler The Lucerne Auction• 1939 1 7 October 2014 to 29 March 2015 La Cité Miroir - Liège Entartete Kunst, according to Hitler 1939 - The Lucerne Auction Picasso, Chagall, Ensor, Kokoschka, Corinth, Derain, … Liège, La Cité Miroir 17 October 2014 to 29 March 2015 An original exhibition bringing together in Liège the works from the Lucerne auction Art and history are combined in an exhibition presented in Liège dedicated to works that were sold by the Germans at the Lucerne auction in 1939. Franz MARC (Munich, 1880 – Verdun, 1916), Pferde auf der Weide, 1910. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège (Bal).© Ville de Liège. On the eve of the Second World War, the Nazi authorities wished to dispose of the Modern art works in display in German art galleries that they considered “degenerate”. In June 1939, they organised a grand auction in Lucerne. This auction, which was to take on a historic dimension, offered works by some of the greatest artists of the period: Gauguin, Chagall, Matisse, Kokoschka and even Picasso… The Belgian government was represented at the auction, as was a delegation from Liège that had managed to raise quite a large sum. Belgium acquired several works of art for the museums of Antwerp and Brussels while Liège purchased nine exceptional paintings that today form part of the city’s major collections. Now scattered around the world in prestigious private and public collections, a large number of the works from the auction will be brought together for the first time and exclusively presented at the Cité Miroir in Liège. -

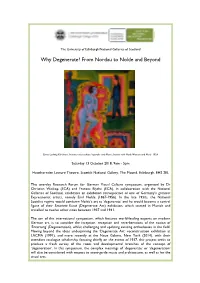

Why Degenerate? from Nordau to Nolde and Beyond

The University of Edinburgh/National Galleries of Scotland Why Degenerate? From Nordau to Nolde and Beyond Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Interieur mit nackter Liegender und Mann (Interior with Nude Woman and Man), 1924 Saturday 13 October 2018, 9am - 5pm Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery, The Mound, Edinburgh, EH2 2EL This one-day Research Forum for German Visual Culture symposium, organised by Dr Christian Weikop (ECA) and Frances Blythe (ECA), in collaboration with the National Galleries of Scotland, celebrates an exhibition retrospective of one of Germany’s greatest Expressionist artists, namely Emil Nolde (1867-1956). In the late 1930s, the National Socialist regime would condemn Nolde’s art as ‘degenerate’ and he would become a central figure of their Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition, which started in Munich and travelled to twelve other cities between 1937 and 1941. The aim of this international symposium, which features world-leading experts on modern German art, is to consider the inception, reception and reverberations of the notion of ‘Entartung’ (Degeneration), whilst challenging and updating existing orthodoxies in the field. Moving beyond the ideas underpinning the ‘Degenerate Art’ reconstruction exhibition at LACMA (1991), and more recently at the Neue Galerie, New York (2014), with their attendant catalogue scholarship focusing chiefly on the events of 1937, this project seeks to produce a fresh survey of the roots and developmental branches of the concept of ‘degeneration’. In this symposium, the -

Aspects of Inner Emigration in Hannah Höch 1933 – 1945

Aspects of Inner Emigration in Hannah Höch 1933 – 1945 Monika Wenke, M.A.S. January 2010 This paper was submitted and accepted as dissertation in History of Art at the University of Cambridge to Prof. Francis Woodman, tutor Dr. Andrew Lacey, Institute for Continuing Education in January 2010. The Dissertation received a first class degree (75%). II Abstract The Third Reich is still a sore point in German history and in many areas it is still rarely dealt with. This also applies to many artists who did not flee Nazi Germany but are known as artists of the “inner emigration” such as the German artist Hannah Höch. The dissertation closes this gap in the reception of Hannah Höch by analyzing and reviewing this “dark period” from 1933 to 1945. In public perception the “inner emigration” of artists is a very controversial theme that went from total ignorance of the fact to denial and accusations of corruption to an idealization as the only true resistance. The essay illustrates Hannah Höch’s personal path into inner emigration and shows how she survived between opposition and conformity. Using public records in addition to diaries and personal statements, it clears up some common misconceptions. III Declaration This is substantially my own work and where reference has been made to other research, this has been acknowledged in the references and bibliography. Monika Wenke, MAS, January 2010 IV Acknowledgements Many thanks to my supervisor Dr. Andrew Lacey for his ideas and input, his assistance with spelling and most of all for his endless patience. Many thanks as well to Dr. -

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives EDITED BY LOUISE HARDIMAN AND NICOLA KOZICHAROW To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives Edited by Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Copyright of each chapter is maintained by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Paul Klee and His Illness, Scleroderma

Paul Klee and his illness, scleroderma Richard M. Silver, MD The author (AΩA, Vanderbilt University, 1975) is profes- sor of Medicine and Pediatrics and director of the Division of Rheumatology and Immunology at the Medical University of South Carolina. t has been said that the viewing and analyzing of fine art from a medical perspective increases one’s appreciation of the in- dividual’s suffering and teaches us an important lesson of the humanI aspects of medicine.1 It is likely that few artists suffered as greatly as did Paul Klee, one of the pioneers of modern art. Klee suffered personal loss, intellectual and political persecution, and, finally, a devastat- ing illness, scleroderma. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) is characterized by autoimmunity, microvascular injury, and an overproduction of collagen and other extracellular matrix components, often leading to profound changes in personal appearance, significant morbidity, and, in many cases, reduced survival. Despite his fatal illness, Klee’s adaptation and artistic productivity provide a window through which one can appreciate the indomitable spirit of human creativity. Paul Klee was born on December 18, 1879, in the small town of Münchenbuchsee near Bern, Switzerland.2,3 His mother, Ida Maria Frick, was a trained singer, and his father, Hans Klee, taught music for fifty years at the Cantonal School for Teachers near Bern.4 Both envisioned a musical career for Paul, who indeed was a talented violinist, earning a seat with the Bern City Orchestra. From a very early age, though, it was drawing and art that captured the imagination of Paul Klee, although music accompanied him throughout his life and in his art. -

Chapters from General Works on Nazi Art

CONSTRUCTUING THE CATEGORY ENTARTETE KUNST: THE DEGENERATE ART EXHIBITION OF 1937 AND POSTMODERN HISTORIOGRAPHY A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy J. Michael McKeon March 2006 This dissertation entitled CONSTRUCTUING THE CATEGORY ENTARTETE KUNST: THE DEGENERATE ART EXHIBITION OF 1937 AND POSTMODERN HISTORIOGRAPHY by J. MICHAEL MCKEON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Charles S. Buchanan Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts Chuck McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract MCKEON, J. MICHAEL, Ph.D., March 2006. Interdisciplinary Arts CONSTRUCTING THE CATEGORY ENTARTETE KUNST: THE DEGENERATE ARTS EXHIBITION OF 1937 AND POSTMODERN HISTORIOGRAPHY (229 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Charles S. Buchanan This study, utilizing Michel Foucault’s theory from which to interpret visual abnormality in art, analyzes the reasons why the Nazis believed visual dysfunction and mental illness were the operative forces behind modern art. In Munich, Germany in 1937 the National Socialist party, fearing that German culture was slowly degenerating into madness, sponsored two art events largely for the purposes of contrast. At the largely monolithic Great German Art Exhibition the Nazis hastened to forward their own aesthetic vision by displaying art works representing human forms in the language of classicism. The Degenerate Art Exhibition (held a day later) showcased early twentieth- century German avant-garde paintings, which, the Nazis claimed, were the products of abnormal vision and mental illness. The importance of visual perception in art is first detected in the period Foucault identifies as the Classical episteme, a period that regards man’s capacity for representation as the primary tool for ordering knowledge about the world.