Guide to the Exhibition Degenerate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erich Heckel (Döbeln 1883 - Radolfzell 1970)

Erich Heckel (Döbeln 1883 - Radolfzell 1970) Selfportrait,1968 Artist description: Erich Heckel began studying architecture in 1904 at the Technical University in Dresden, but left the university again one year later. Heckel prepared the ground for Expressionism when he founded the artist group "Die Brücke" together with his friends Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Fritz Bleyl and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in 1905. The artist now concentrated on various printing techniques such as woodcut, lithograph and engraving. He produced landscapes in dazzling colours. In the autumn of 1911 Heckel moved to Berlin. He was acquainted with Max Pechstein, Emil Nolde and Otto Mueller who had joined the "Brücke" artists and now met Franz Marc, August Macke and Lyonel Feininger. In 1912 Erich Heckel painted the murals for the chapel of the "Sonderbund Exhibition" in Cologne together with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. "Die Brücke" was dissolved in the following year and Gurlitt arranged Heckel's first one-man-exhibition in Berlin. Erich Heckel spent the years 1915 - 1918 in Flanders as a male nurse with the Red Cross and then returned to Berlin where he remained until the beginning of 1944. Heckel spent most summers on the Flensburger Förde while his many travels took him to the Alps, Southern France, Northern Spain and Northern Italy. 729 of his works were confiscated in German museums in 1937 and his studio in Berlin was destroyed in an air raid in Berlin shortly before the end of the war, destroying all his printing blocks and many of his works. Heckel subsequently moved to Hemmenhofen on Lake Constance. In 1949 he was appointed professor at the "Akademie der Bildenden Künste" in Karlsruhe, a post that he held until 1955. -

Galerie Thomas Spring 2021

SPRING 20 21 GALERIE THOMAS All works are for sale. Prices upon requesT. We refer To our sales and delivery condiTions. Dimensions: heighT by widTh by depTh. © Galerie Thomas 20 21 © VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21: Josef Albers, Hans Arp, STephan Balkenhol, Marc Chagall, Serge Charchoune, Tony Cragg, Jim Dine, OTTo Dix, Max ErnsT, HelmuT Federle, GünTher Förg, Sam Francis, RupprechT Geiger, GünTer Haese, Paul Jenkins, Yves Klein, Wifredo Lam, Fernand Léger, Roy LichTensTein, Markus LüperTz, Adolf LuTher, Marino Marini, François MorelleT, Gabriele MünTer, Louise Nevelson, Hermann NiTsch, Georg Karl Pfahler, Jaume Plensa, Serge Poliakoff, RoberT Rauschenberg, George Rickey, MarTin Spengler, GünTher Uecker, VicTor Vasarely, Bernd Zimmer © Fernando BoTero, 20 21 © Lucio FonTana by SIAE / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © PeTer Halley, 20 21 © Nachlass Erich Heckel, Hemmenhofen 20 21 © Rebecca Horn / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Nachlass Jörg Immendorff 20 21 © Anselm Kiefer 20 21 © Successió Miró / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Nay – ElisabeTh Nay-Scheibler, Cologne / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © STifTung Seebüll Ada und Emil Nolde 20 21 © Nam June Paik EsTaTe 20 21 © PechsTein – Hamburg/Tökendorf / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © The EsTaTe of Sigmar Polke, Cologne / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Marc Quinn 20 21 © Ulrich Rückriem 20 21 © Succession Picasso / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Simon SchuberT 20 21 © The George and Helen Segal FoundaTion / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © KaTja STrunz 2021 © The Andy Warhol FoundaTion for The Visual ArTs, Inc. / ArTisTs RighTs SocieTy (ARS), New York 20 21 © The EsTaTe of Tom Wesselmann / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 All oTher works: The arTisTs, Their esTaTes or foundaTions cover: ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY PorTraiT of a Girl KEES VAN DONGEN oil on cardboard, painTed on boTh sides – Farmhouse Garden, p. -

The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 Denali Elizabeth Kemper CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/661 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 By Denali Elizabeth Kemper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis sponsor: January 5, 2021____ Emily Braun_________________________ Date Signature January 5, 2021____ Joachim Pissarro______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents Acronyms i List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Points of Reckoning 14 Chapter 2: The Generational Shift 41 Chapter 3: The Return of the Repressed 63 Chapter 4: The Power of Nazi Images 74 Bibliography 93 Illustrations 101 i Acronyms CCP = Central Collecting Points FRG = Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany GDK = Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) GDR = German Democratic Republic, East Germany HDK = Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) MFAA = Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program NSDAP = Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s or Nazi Party) SS = Schutzstaffel, a former paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany ii List of Illustrations Figure 1: Anonymous photographer. -

16 Forse Mai, O Forse in Paradiso MINICATALOGUE

¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¥ ¨ ¥ © ¥ ¥ ¥ ¦ ¥ ¦ ¦ § ¥ ¤ ¦ §¥ ¨¥© £¥¤ £ ¨ ! "# # $#$# $$ % & ' ¨ %()* ¦ + $ , % ( - ( - % ( .. .. & / 0 , % ( - ( - % ( .. 1 222 + & 3 # # & # ! + & 22 2+ & 3 # # !+ FORSE MAI, O FORSE IN PARADISO NOT HERE, BUT CERTAINLY IN HEAVEN Giovanni Manfredini, the artists of „Brücke“ and their successors on the theme of „Religion“ Left: Giovanni Manfredini, Stabat Mater, silver plated 2014, diameter 33 cm. Signed. Obj. Id 79808. Right: Hermann Max Pechstein, Vater Unser, Portfolio with 12 Woodcuts 1921, Edition B: Exemplar 121 of 250, each print is signed, paper size 41 x 60 cm. Obj. Id: 80154 2nd September until 26th November 2016 ¢ ¨ ## ¦+ $ 24$# ¢ ¨ ## £¢ "!+#!+ 5$# 6 3$$$!+ $ ¢42# ¢ & 5$#+54 & 5$#5!++54 &74 & £!+6 £5$$#54 & £358 & 7358 & 99$$ & !+:#54 #54 ;4!+ 359## ¥!+#+# $654 7$!+54 $<# <# 5 4$#$!+ #554 6 5$#5$$#54 5 5$#$9954 $#4&/#4 (= & () , (% (1 >+ & 9$#4 (= & (- >+ ¢£¤¥¦§¥ ¨¥© ¥ ¥ ¥¦¥¦ ¦§¥¤ ¦§¥¨¥©£¥¤ £ ¨ ! "##$#$#$$ % & '¨ %()* ¦+$ ,%(-(-%( .. .. & /0 ,%(-(-%( .. .1 222+&3##&#!+ & 222+&3##!+ FORSE MAI, O FORSE IN PARADISO NOT HERE, BUT CERTAINLY IN HEAVEN Giovanni Manfredini, the artists of “Brücke” and their successors on the theme of “Religion” nd th 2 September until 26 November 2016 Besides allegorical and historical representations, paintings and sculptures devoted to religious themes also became firmly established very early on in the history of art. By the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans, at the latest, their gods and their deeds, histories -

Berger ENG Einseitig Künstlerisch

„One-sidedly Artistic“ Georg Kolbe in the Nazi Era By Ursel Berger 0 One of the most discussed topics concerning Georg Kolbe involves his work and his stance during the Nazi era. These questions have also been at the core of all my research on Kolbe and I have frequently dealt with them in a variety of publications 1 and lectures. Kolbe’s early work and his artistic output from the nineteen twenties are admired and respected. Today, however, a widely held position asserts that his later works lack their innovative power. This view, which I also ascribe to, was not held by most of Kolbe’s contemporaries. In order to comprehend the position of this sculptor as well as his overall historical legacy, it is necessary, indeed crucial, to examine his œuvre from the Nazi era. It is an issue that also extends over and beyond the scope of a single artistic existence and poses the overriding question concerning the role of the artist in a dictatorship. Georg Kolbe was born in 1877 and died in 1947. He lived through 70 years of German history, a time characterized by the gravest of political developments, catastrophes and turning points. He grew up in the German Empire, celebrating his first artistic successes around 1910. While still quite young, he was active (with an artistic mission) in World War I. He enjoyed his greatest successes in the Weimar Republic, especially in the latter half of the nineteen twenties—between hyperinflation and the Great Depression. He was 56 years old when the Nazis came to power in 1933 and 68 years old when World War II ended in 1945. -

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18)

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18) São Paulo, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Apr 25–27, 2018 Deadline: Mar 9, 2018 Erika Zerwes In 1937 the German government, led by Adolf Hitler, opened a large exhibition of modern art with about 650 works confiscated from the country's leading public museums entitled Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst). Marc Chagall, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian and Lasar Segall were among the 112 artists who had works selected for the show. Conceived to be easily assimilated by the general public, the exhibition pre- sented a highly negative and biased interpretation of modern art. The Degenerate Art show had a rather large impact in Brazil. There have been persecutions to modern artists accused of degeneration, as well as expressions of support and commitment in the struggle against totalitarian regimes. An example of this second case was the exhibition Arte condenada pelo III Reich (Art condemned by the Third Reich), held at the Askanasy Gallery (Rio de Janeiro, 1945). The event sought to get support from the local public against Nazi-fascism and to make modern art stand as a synonym of freedom of expression. In the 80th anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in partnership with the Lasar Segall Museum, holds the International Seminar “Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil”. The objective is to reflect on the repercus- sions of the exhibition Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) in Brazil and on the persecution of mod- ern art in the country in the first half of the 20th century. -

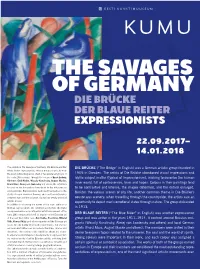

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976 Devotion Woodcut, 1912 Schmidt-Rotluff was one of the founding members ofDie Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden in 1905, along with Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Fritz Bleyl, and joined by Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein. The group disbanded in 1913, largely due to their varying styles and independent moves to Berlin, but each remained true to their rejection of European academic painting and conventions in favor of exploring the vitality and directness of non-Western art forms, particularly West African masks and Oceanic art, as well as revitalization of the pre-Renaissance tradition of German woodcuts. Devoción Xilografía, 1912 Schmidt-Rottluff fue uno de los miembros fundadores de Die Brücke (El puente) en Dresde en 1905, junto con Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner y Fritz Bleyl, grupo al que se unieron luego Emil Nolde y Max Pechstein. El grupo se disolvió en 1913, en gran parte debido a la evolución de sus estilos y a los traslados individuales de los artistas a Berlín, pero cada uno de ellos permaneció fiel al rechazo de la pintura y las convenciones academicistas europeas, en favor de la exploración de la vitalidad y la franqueza de formas artísticas no occidentales, especialmente las máscaras de África occidental y el arte de Oceanía, así como de la revitalización de la xilografía alemana de tradición prerrenacentista. Museum purchase through the Earle W. Grant Acquisition Fund, 1975.37 KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976 Head of a Woman Woodcut, 1909 “I know that I have no program, only the unaccountable longing to grasp what I see and feel, and to find the purest means of expressing it.” Studying Japanese techniques of woodcuts, as well as the techniques of Albrecht Dürer, Paul Gauguin, and Edvard Munch, Schmidt-Rottluff produced powerful images, evoking intense psychological states through the flattening of form and retention of traces of roughly hewn wood blocks. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156. -

Kees Van Dongen Max Ernst Alexej Von Jawlensky Otto Mueller Emil Nolde Max Pechstein Oskar Schlemmer

MASTERPIECES VIII KEES VAN DONGEN MAX ERNST ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY OTTO MUELLER EMIL NOLDE MAX PECHSTEIN OSKAR SCHLEMMER GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES VIII GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY MAX ERNST STILL LIFE WITH JUG AND APPLES 1908 6 FEMMES TRAVERSANT UNE RIVIÈRE EN CRIANT 1927 52 PORTRAIT C. 191 616 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY MAX PECHSTEIN HOUSE WITH PALM TREE 191 4 60 INTERIEUR 1922 22 OSKAR SCHLEMMER EMIL NOLDE ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE R 191 9 68 YOUNG FAMILY 1949 30 FIGURE ON GREY GROUND 1928 69 KEES VAN DONGEN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY PORTRAIT DE FEMME BLONDE AU CHAPEAU C. 191 2 38 WOMAN IN RED BLOUSE 191 1 80 EMIL NOLDE OTTO MUELLER LANDSCAPE (PETERSEN II) 1924 44 PAIR OF RUSSIAN GIRLS 191 9 88 4 5 STILL LIFE WITH JUG AND APPLES 1908 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY oil on cardboard Provenance 1908 Studio of the artist 23 x 26 3/4 in. Adolf Erbslöh signed lower right, Galerie Otto Stangl, Munich signed in Cyrillic and Private collection dated lower left Galerie Thomas, Munich Private collection Jawlensky 21 9 Exhibited Recorded in the artist’s Moderne Galerie, Munich 191 0. Neue Künstlervereinigung, II. Ausstellung. No. 45. photo archive with the title Galerie Paul Cassirer, Berlin 1911 . XIII. Jahrgang, VI. Ausstellung. ‘Nature morte’ Galerie Otto Stangl, Munich 1948. Alexej Jawlensky. Image (leaflet). Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris; Haus der Kunst Munich, 1966. Le Fauvisme français et les débuts de l’Expressionisme allemand. No. 164, ill. p.233. Ganserhaus, Wasserburg 1979. Alexej von Jawlensky – Vom Abbild zum Urbild. No. 18, ill. p.55. -

An Artist Against the Third Reich Ernst Barlach, 1933–1938

CY132/Paret-FM CY132/Paret 0 5218213 8 November 21, 2002 12:21 Char Count= 0 An Artist against the Third Reich Ernst Barlach, 1933–1938 PETER PARET Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton iii CY132/Paret-FM CY132/Paret 0 5218213 8 November 21, 2002 12:21 Char Count= 0 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http: // www.cambridge.org C Peter Paret 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United States of America Typefaces Janson Text 11/16 pt. and Berliner Grotesk System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Paret, Peter. An artist against the Third Reich : Ernst Barlach, 1933–1938 / Peter Paret. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-82138-x (hardback) 1. Barlach, Ernst, 1870–1938. 2. Nationalsocialismand art. 3. Germany – Politics and government – 1933–1945. 4. Modernism (Art) – Germany. i. Title. n6888.b35 p37 2002 700.92–dc21 2002073616 isbn 0 521 82138 x hardback iv CY132/Paret-FM CY132/Paret 0 5218213 8 November 21, 2002 12:21 Char Count= 0 Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Hitler 5 2 Barlach 23 3 Nordic Modernism 51 4 The Hounding of Barlach 77 5 German and Un-German Art 109 6 After the Fact 139 A Note on the Literature 155 Notes 167 Documents and Works Cited 183 Index 189 vii CY132/Paret-FM CY132/Paret 0 5218213 8 November 21, 2002 12:21 Char Count= 0 Illustrations The illustrations follow p. -

4C the Anti-Modernists

seum, were some six hundred and fifty the art world of the twenty thousand works that the Nazis eventually confiscated from Ger- man institutions and collections. Many The anti-MOdERNisTs were subsequently burned; others were sold abroad, for hard currency. Wall texts Why the Third Reich targeted artists. noted the prices that public museums had paid for the works with “the taxes of the BY PETER sCHjEldAHl German working people,” and derided the art as mentally and morally diseased or as a “revelation of the Jewish racial soul.” Only a handful of the artists were Jews, but that made scant difference to a regime that could detect Semitic conta- gion anywhere. Some months earlier, Jo- seph Goebbels, the propaganda minister, had announced a ban on art criticism, as “a legacy of the Jewish influence.” “Degenerate Art” was a blockbuster, far outdrawing a show that had opened the day before, a short walk away, in a new edifice, dear to Hitler, called the House of German Art. “The Great German Art Exhibition” had been planned to demonstrate a triumphant new spirit in the nation’s high culture, but the preponderance of academic hackery in the work produced for it came as a rankling disappointment to Hitler, whose taste was blinkered but not blind. By official count, more than two million visitors thronged “Degen- erate Art” during its four-month run in Munich. Little is recorded of what they thought, but the American critic A. I. Philpot remarked, in the Boston Globe, that “there are probably plenty of people—art lovers—in Boston who will side with Hitler in this particular purge.” Germany had no monopoly on ou might not expect much drama the works.