The Journey of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Self-Portrait As a Soldier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

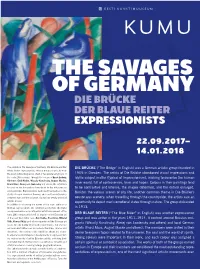

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976 Devotion Woodcut, 1912 Schmidt-Rotluff was one of the founding members ofDie Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden in 1905, along with Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Fritz Bleyl, and joined by Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein. The group disbanded in 1913, largely due to their varying styles and independent moves to Berlin, but each remained true to their rejection of European academic painting and conventions in favor of exploring the vitality and directness of non-Western art forms, particularly West African masks and Oceanic art, as well as revitalization of the pre-Renaissance tradition of German woodcuts. Devoción Xilografía, 1912 Schmidt-Rottluff fue uno de los miembros fundadores de Die Brücke (El puente) en Dresde en 1905, junto con Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner y Fritz Bleyl, grupo al que se unieron luego Emil Nolde y Max Pechstein. El grupo se disolvió en 1913, en gran parte debido a la evolución de sus estilos y a los traslados individuales de los artistas a Berlín, pero cada uno de ellos permaneció fiel al rechazo de la pintura y las convenciones academicistas europeas, en favor de la exploración de la vitalidad y la franqueza de formas artísticas no occidentales, especialmente las máscaras de África occidental y el arte de Oceanía, así como de la revitalización de la xilografía alemana de tradición prerrenacentista. Museum purchase through the Earle W. Grant Acquisition Fund, 1975.37 KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976 Head of a Woman Woodcut, 1909 “I know that I have no program, only the unaccountable longing to grasp what I see and feel, and to find the purest means of expressing it.” Studying Japanese techniques of woodcuts, as well as the techniques of Albrecht Dürer, Paul Gauguin, and Edvard Munch, Schmidt-Rottluff produced powerful images, evoking intense psychological states through the flattening of form and retention of traces of roughly hewn wood blocks. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156. -

Ernst Kirchner's Streetwalkers: Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16 Author(S): Sherwin Simmons Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Ernst Kirchner's Streetwalkers: Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16 Author(s): Sherwin Simmons Reviewed work(s): Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), pp. 117-148 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051367 . Accessed: 01/10/2012 16:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org Ernst Kirchner's Streetwalkers: Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16 SherwinSimmons An article entitled "Culture in the Display Window," which formulation of Berlin as a whore and representations of surveyed the elegant artistry of Berlin's display windows, fashion contributed to Kirchner's interpretation of the street- appeared in Der Kritiker,a Berlin cultural journal, during the walkers.8 My study extends such claims by examining the summer of 1913. Its author stated that these windows were an impact of specific elements within the discourse about luxury important factor in Germany's recent economic boom and and immorality on Kirchner's work and considering why such the concomitant rise of its culture on the world stage, serving issues would have concerned an avant-garde artist. -

L LIBRARY (109.?) Michigan State

llllllgllllllgfllllfllllllUllllllllllllIIHHIHHIW 01399 _4581 l LIBRARY (109.?) Michigan State University » —.a._——-——_.——__—— ~—_ __._._ .- . v» This is to certify that the 4 thesis entitled The Influence of Walt Whitman on the German Expres- sionist Artists Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, Max Pechstein and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner presented by Dayna Lynn Sadow has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for M.A. History of Art degree in /' l" s in? / l Majo\profe:sor Dateg’v ' ‘0‘ ‘0' 0‘ S 0-7639 MS U is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Institution PLACE N RETURN BOX to remove thh checkout Irom your record. TO AVOID FINES return on or before dete due. DATE DUE DATE DUE DATE DUE fl! l I MSU IeAn Affirmetive ActioNEquel Opportunity Inetituion Wan-94 THE INFLUENCE OF WALT WHITMAN ON THE GERMAN EXPRESSIONIST ARTISTS KARL SCI-[MIDT-ROTTLUFF, ERICH HECKEL, MAX PECHSTEIN AND ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER By Dayna Lynn Sadow A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Art 1994 ABSTRACT THE INFLUENCE OF WALT WHITMAN ON THE GERMAN EXPRESSIONIST ARTISTS KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF, ERICH HECKEL, MAX PECHSTEIN AND ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER By Dayna Lynn Sadow This study examines the relationship between Walt Whitman and the Briicke artists Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, Max Pechstein and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Chapter I analyzes the philosophy of Whitman as reflected in his book Leaves of Grass and explores the introduction of his work into Germany. Chapter II investigates the doctrine of the Briicke artists. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215/842-6353 CONTACT: Katie Ziglar Deb Spears (202) 842-6353 ** Press preview: Wednesday, November 15, 1989 EXPRESSIONIST AND OTHER MODERN GERMAN PAINTINGS AT NATIONAL GAT.T.KRY Washington, D.C., September 18, 1989 Thirty-four outstanding German paintings from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection begin an American tour at the National Gallery of Art, November 19, 1989 through January 14, 1990. Expressionism and Modern German Painting from the Thyssen- Bornemisza Collection contains important examples by artists whose major paintings are extremely rare in this country. The nineteen artists represented in the show include Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Otto Dix, Johannes Itten, Franz Marc, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The intense and colorful works in this exhibition are among the modern paintings Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza has added, along with old master paintings, to the collection he inherited from his father> Baron Heinrich (1875-1947). Expressionism and Modern German Painting, to be seen at three American museums, is selected from the large collection on view at the Baron's home, Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland, through October 29, 1989. It is the first exhibition devoted entirely to the modern German paintings in the collection. -more- expressionism and modern german painting . page two "Comprehensive groupings of expressionism and modern German paintings are extremely rare in American museums and we are pleased to offer a show of this extraordinary caliber here this fall," said J. Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery. The American show has been selected by Andrew Robison, senior curator at the National Gallery. -

Press Release Template

COMMUNICATIONS & MARKETING VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS 200 N. Boulevard I Richmond, Virginia 23220-4007 www.vmfa.museum/pressroom I T 804.204.2704 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 6, 2016 German Expressionist work is reunited with Ludwig and Rosy Fischer Collection at VMFA Kirchner painting currently on view at museum A major painting by German Expressionist artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938), which the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York recently returned to the family of its rightful owner, has been reunited with works from the Ludwig and Rosy Fischer Collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. Sand Hills in Grünau was at the center of a 10-year restitution case that sought to prove MoMA’s painting had once been owned by the son of Ludwig and Rosy Fischer under a different title. Its journey from Frankfurt, Germany, in the 1920s to VMFA today involves the family’s dedication and support of Kirchner and other German Expressionist artists, Nazi-era confiscation of “degenerate” art, provenance research, and a postcard. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (German 1880-1938) Sand Hills in Grünau, circa 1912. Oil on canvas, 33¾ x 37½ in. Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, and gift of Eva Fischer Marx, Thomas Marx, Ludwig and Rosy Fischer were forward-thinking collectors in and Dr. George and Mrs. Marylou Fischer © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Frankfurt, Germany, who collected German Expressionism between 1905 and 1925. Their sons, Ernst and Max, inherited the collection of approximately 500 works in 1926. After the Nazis gained power in Germany, Ernst left the country in 1934 and eventually settled in Richmond, Va., with his half of the collection. -

For Immediate Release August 3, 2006

For Immediate Release August 3, 2006 Contact: Catherine Manson +44.20.7389.2982 [email protected] Toby Usnik +1.212.636.2680 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK TO OFFER KIRCHNER PAINTING IN IMPRESSIONIST AND MODERN ART EVENING SALE OF FALL 2006 Impressionist and Modern Art November 8, 2006 Ernst Ludwig Kircher, Strassenszene, Berlin oil on canvas, painted in 1913 47.5/8 x 37.3/8 in. (121 x 95 cm). New York – Christie’s New York is honored to announce the sale of Strassenszene, Berlin, (Street Scene, Berlin) of 1913, by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner during the Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale on November 8. The painting was restituted by the Brücke-Museum in Berlin to the heirs of Alfred and Thekla Hess this past July. The work is expected to realize in excess of $18 – 25 million (£10 – 14 million / €14 – €20 million). “We are thrilled to offer this outstanding work by Kirchner in our evening sale this November,” says Guy Bennett, Senior Vice President and Head of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Art Page 1 of 4 department in New York. “It is one of the 20th Century’s first and finest expressions of metropolitan life. The painting is both an icon of Expressionism and of this troubled generation’s ambiguous relationship with modernity.” “Strassenszene, Berlin from 1913 is a tour de force that captures the theme of the human being in a large metropolis on the edge of profound change,” adds Andreas Rumbler, Head of Christie’s Germany. “It is the most significant German Expressionist picture ever to come to auction and we are pleased to continue Christie’s tradition of offering milestones of German art at our upcoming sale. -

Expressionism in Germany and France: from Van Gogh to Kandinsky

^ Exhibition Didactics Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky Private Collectors French avant-garde art was being avidly collected and exhibited in Germany, especially by private collectors, who did not have the same constraints that museum directors and curators faced. Karl Ernst Osthaus was one of the most passionate and important collectors and a fervent supporter of the German Expressionists. In 1902 Osthaus opened the Museum Folkwang in Hagen (today the museum is in Essen). There he exhibited his own collection, including the works of Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Paul Signac. His museum was frequented by admirers of avant-garde art, including many of the new generation of Expressionists, among them August Macke, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, and Christian Rohlfs (who later moved to Hagen and had a studio at the museum). The cosmopolitan Count Harry Kessler, who grew up partly in Paris and later divided his time between France and Germany, discovered Neo-Impressionism early through the works of Signac and Théo van Rysselberghe, which he saw in Paris. He was also interested in the French artists group known as the Nabis, and acquired The Mirror in the Green Room (on view in this exhibition) by Pierre Bonnard, one of its members. Kessler also commissioned works from French painters, including Henri-Edmond Cross’s Bather , also on view in this exhibition. In 1905, when he was the director of the Grand Ducal Museum in Weimar, Kessler organized the first major Gauguin exhibition in Germany. Although it provoked a scandal— Gauguin was criticized for being too “exotic”—the exhibition presented the artist’s colorful Symbolist paintings of Brittany and Tahiti to the German art world. -

Outstanding Works of German Expressionism at Villa Grisebach's

Outstanding works of German Expressionism at Villa Grisebach’s autumn auctions Villa Grisebach’s autumn auctions from November 27 until 30 present 1294 works of art with a median pre-sale estimate of 18 million euros. Masterworks of Modern Art form the traditional focus, while the Photography, 19th Century Art and Contemporary Art sections find themselves expanded again. Selected Objects of the decorative and fine arts enrich the discriminating offerings of the four-day sales in the ORANGERIE auction (see separate press release). The sales’ opening auction is 19th Century Art on November 27: A late, finished master drawing by Adolph Menzel created in 1894 in Karlsbad deserves special attention (estimate € 50,000 / 70,000) much as the preliminary study in oil for Max Liebermann’s famous “Flachsscheuer” painting at Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin (€ 140,000 / 180,000). After the ORANGERIE auction on the morning of November 28, Selected Works presents from 5 PM a selection of highlights that span the entire 20th century: This evening sale begins with Paula Modersohn-Becker’s painting, “Landschaft mit Moortümpel,” from 1900; it ends with Thomas Demand’s photograph, “Campingtisch” from 1999. In between, modern master works of museum quality are on offer: Max Liebermann’s painting “Garten in Noordwijk-Binnen” of 1909 (€ 500,000 / 700,000) and his “Blumenterrasse im Wannseegarten nach Nordwesten” of 1915 (€ 350,000 / 500,000). The leading artist groups of German Expressionism, “Die Brücke” and “Der Blaue Reiter,” are represented with important works. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s “Watt bei Ebbe” is a museum quality example for the Expressionists’ new will around 1912 to experiment with composition and powerful colors (€ 1,000,000 / 1,500,000). -

Expressionism in Germany and France: from Van Gogh to Kandinsky

LACM A Exhibition Checklist Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky Cuno Amiet Mutter und Kind im Garten (Mother and Child in Garden) (circa 1903) Oil on canvas Canvas: 27 11/16 × 24 3/4 in. (70.4 × 62.8 cm) Frame: 32 1/2 × 28 9/16 × 2 1/4 in. (82.5 × 72.5 × 5.7 cm) Kunstmuseum Basel Cuno Amiet Bildnis des Geigers Emil Wittwer-Gelpke (1905) Oil on canvas Canvas: 23 13/16 × 24 5/8 in. (60.5 × 62.5 cm) Frame: 27 3/4 × 28 9/16 × 2 5/8 in. (70.5 × 72.5 × 6.7 cm) Kunstmuseum Basel Pierre Bonnard The Mirror in the Green Room (La Glace de la chambre verte) (1908) Oil on canvas Canvas: 19 3/4 × 25 3/4 in. (50.17 × 65.41 cm) Frame: 27 × 33 1/8 × 1 1/2 in. (68.58 × 84.14 × 3.81 cm) Indianapolis Museum of Art Georges Braque Paysage de La Ciotat (1907) Oil on canvas Overall: 14 15/16 x 18 1/8 in. (38 x 46 cm) K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen Georges Braque Violin et palette (Violin and Palette) (1909-1910) Oil on canvas Canvas: 36 1/8 × 16 7/8 in. (91.76 × 42.86 cm) Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Heinrich Campendonk Harlequin and Columbine (1913) Oil on canvas Canvas: 65 × 78 3/8 in. (165.1 × 199.07 cm) Frame: 70 15/16 × 84 3/16 × 2 3/4 in. (180.2 × 213.8 × 7 cm) Saint Louis Art Museum Page 1 Paul Cézanne Grosses pommes (Still Life with Apples and Pears) (1891-1892) Oil on canvas Canvas: 17 5/16 × 23 1/4 in. -

The Mysteries of Material. Kirchner, Heckel and Schmidt-Rottluff

SHORT BIOGRAPHIES THE MYSTERIES OF MATERIAL. KIRCHNER, HECKEL AND SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF 26 June to 13 October 2019 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER 1880 Born on 6 May in Aschaffenburg, the son of a paper chemist 1901–1905 Study of architecture at the Technische Hochschule Dresden, degree 1905 Co-founder of the artists’ group Brücke 1909–1911 Summer excursions with Heckel to the Moritzburg Ponds near Dresden 1910 Visit to the collector Gustav Schiefler (1857–1935) – one of the Brücke artists’ most important patrons and the author of the catalogue raisonné of Kirchner’s printmaking œuvre (1926/31) – in Hamburg 1911 Move to Berlin, meets his later life companion Erna Schilling (1884– 1945) 1912–1914 Regular summer stays on the North Sea island of Fehmarn 1913 Disbandment of Brücke 1915 Military service in Halle (Saale) for just a few months before suffering a nervous breakdown; in the autumn, release from the military; stays in different sanatoria 1916–1922 Exhibitions in the gallery of Ludwig Schames (1852–1922) in Frankfurt 1917 Move to Switzerland; stay of several months in the Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen on Lake Constance 1918 Move to a farmhouse outside of Frauenkirch near Davos 1925/26 Last visit to Germany with stop in Frankfurt am Main 1937 Labelled a “degenerate artist” 1938 Commits suicide on 15 June in Frauenkirch-Wildboden near Davos ERICH HECKEL 1883 Born on 31 July in Döbeln, the son of a railway construction engineer from 1902 Friendship with Karl Schmidt(-Rottluff) 1904–1906 Study of architecture at the Technische Hochschule Dresden