Aspects of Inner Emigration in Hannah Höch 1933 – 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

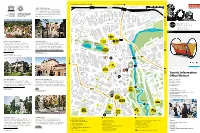

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18)

Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil (São Paulo, 25-27 Apr 18) São Paulo, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Apr 25–27, 2018 Deadline: Mar 9, 2018 Erika Zerwes In 1937 the German government, led by Adolf Hitler, opened a large exhibition of modern art with about 650 works confiscated from the country's leading public museums entitled Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst). Marc Chagall, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian and Lasar Segall were among the 112 artists who had works selected for the show. Conceived to be easily assimilated by the general public, the exhibition pre- sented a highly negative and biased interpretation of modern art. The Degenerate Art show had a rather large impact in Brazil. There have been persecutions to modern artists accused of degeneration, as well as expressions of support and commitment in the struggle against totalitarian regimes. An example of this second case was the exhibition Arte condenada pelo III Reich (Art condemned by the Third Reich), held at the Askanasy Gallery (Rio de Janeiro, 1945). The event sought to get support from the local public against Nazi-fascism and to make modern art stand as a synonym of freedom of expression. In the 80th anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in partnership with the Lasar Segall Museum, holds the International Seminar “Degenerate Art – 80 Years: Repercussions in Brazil”. The objective is to reflect on the repercus- sions of the exhibition Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) in Brazil and on the persecution of mod- ern art in the country in the first half of the 20th century. -

German Expressionism: the Second Generation (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988): 10-37

Stephanie Barron, “Introduction” to Barron (ed.), German Expressionism: The Second Generation (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988): 10-37. The notion that all the significant achievements of German Expressionism occurred before 1914 is a familiar one. Until recently most scholars and almost all exhibitions of German Expressionist work have drawn the line with the 1913 dissolution of Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Berlin or the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Peter Selz’s pioneering study German Expressionist Painting, published in 1957, favored 1914 as a terminus as did Wolf-Dieter Dube’s Expressionism, which appeared in 1977. It is true that by 1914 personal differences had led the Brücke artists to dissolve their association, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) had disintegrated when Wassily Kandinsky returned from Munich to Russia and Franz Marc volunteered for war service. Other artists’ associations also broke up when their members were drafted. Thus, the outbreak of the war has provided a convenient endpoint for many historians, who see the postwar artistic activities of Ernst Barlach, Max Beckmann, Oskar Kokoschka, Kathe Kollwitz, and others as individual, not group responses and describe the 1920s as the period of developments at the Bauhaus in Weimar or of the growing popularity of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). The years 1915-25 have been lost, or certainly not adequately defined, as a coherent and potent, albeit brief, idealistic period in the evolution of German Expressionism. More recent scholarship, including Dube’s Expressionists and Expressionism (1983) and Donald E. Gordon’s Expressionism- Art and Idea (1987), sees the movement as surviving into the 1920s. -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019 OBJECT LIST Founding the Bauhaus Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar) 1919 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871–1956), illustrator Letterpress and woodcut on paper 850513 Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar (Idea and structure of the State Bauhaus Weimar) Munich: Bauhausverlag, 1923 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Letterpress on paper 850513 Bauhaus Seal 1919 Peter Röhl (German, 1890–1975) Relief print From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, January 1921) 850513 Bauhaus Seal Oskar Schlemmer (German, 1888–1943) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 Diagram of the Bauhaus Curriculum Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 1 The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100, Los Angeles, CA 90049 www.getty.edu German Expressionism and the Bauhaus Brochure for Arbeitsrat für Kunst Berlin (Workers’ Council for Art Berlin) 1919 Max Pechstein (German, 1881–1955) Woodcut 840131 Sketch of Majolica Cathedral 1920 Hans Poelzig (German, 1869–1936) Colored pencil and crayon on tracing paper 870640 Frühlicht Fall 1921 Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938), editor Letterpress 84-S222.no1 Hochhaus (Skyscraper) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (German, 1886–1969) Offset lithograph From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. 122–23 84-S222.no4 Ausstellungsbau in Glas mit Tageslichtkino (Exhibition building in glass with daylight cinema) Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938) Offset lithographs From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. -

Biografie Georg Muche

Georg Muche Biografie 1895 Georg Muche wird am 8. Mai als Sohn eines Beamten in Querfurt geboren. Er verbringt Kindheit und Jugend in der Rhön. 1913 Studium der Malerei an der Azbé-Schule in München, das er nach einem Jahr aufgibt und nach Berlin geht. Lernt Arbeiten von Wassily Kandisky kennen. Im Spätsommer 1913 besuchte ich in München das Atelier, in dem Kandinsky und Jawlensky vor Jahren Malen gelernt hatten. Ich musste dort in der Art von Wilhelm Leibl Köpfe und Akte mit Glanzlichtern auf der Nasenspitze zeichnen und mein Handwerk gründlich erlernen…So jung am Jahren war ich aufgebrochen und kam doch zu spät. Eine Besucherin der Ausstellung („Der blaue Reiter“) muss das Staunen beobachtet haben, mit dem meine Augen auf den Bildern verweilten. Es war Marianne von Werefkin. Sie machte mich aufmerksam auf Jawlensky und Kandinsky, die im Hintergrund miteinander sprachen...Sie hatten die neue Welt entdeckt! Ich erkannte zugleich, dass ich in abstrakten Gefilden nicht suchen durfte, wenn ich Entdeckungen machen wollte. 1915 Zusammenarbeit mit Herwarth Walden im „Sturm“. Ein Jahr später erste Ausstellung in der „Sturm“-Galerie mit Max Ernst, später weitere Ausstellungen mit Alexander Archipenko und Paul Klee. Muche wird wegen seiner außergewöhnlichen Fähigkeiten Lehrer an der „Sturm“- Kunstschule. Theodor Däubler schilderte jene Bilder in seinen Kritiken: „Die geometrisch unbeweglichen Bilder des jungen Georg Muche erinnern an Maschinen im weißglühenden und rotglühenden Zustand…Nicht Vorgänge unter Menschen beschäftigen seine Einbildungskraft, sondern eine Art übersinnlicher Dimension, ein Wissen um Raumbedingtheiten, damit Eruptionen von Leidenschaften in die Welt hereinbrechen können, oder er steigert den Zufall, dass eine Kugel in einem vom Rahmen eingeschlossenen Raum sich öffnet oder verschließt. -

Colour, Form, Painting

MODULE 8 Colour, form, painting SCHOOL, WORKSHOP Age 12–15, 2 Hours, 3 Lessons School, Workshop Age 12–15, 2 hours, 3 lessons Painting, collage Theory of colour, theory of form, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee YOU WILL NEED A4 paper, A3 paper, coloured paper, coloured pencils, watercolours, scissors, glue sticks, colour copies of paintings by Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee INSTRUCTIONS In this module participants learn about the theory of form and colour, and about the painting of the famous artists, Bauhaus masters and pioneers of abstract art, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. First they examine selected works by the two artists and investigate the effect and expression of colour and form. Then they produce their own interpretations using techniques of painting and collage. Step 1: The group examines paintings by Kandinsky and Klee. Participants describe what they see and what figures they can discover. There are no limits to the imagination here. Step 2: In the next step special attention is paid to colours, lines and basic geometrical forms. Which elements appear? How are they combined with one another? Can the paintings be completely reduced to geometrical forms (circles, triangles, squares and rectangles)? Step 3: Now colour copies of the paintings are distributed and the participants cut out the geometrical forms. They rearrange these to make their own collages, combining elements from different paintings and using coloured pencils and watercolours to create their own figures. Additional geometrical forms can be cut out of coloured paper and included in the collages. Step 4: Finally the pictures are displayed on the wall and viewed by the group. -

4C the Anti-Modernists

seum, were some six hundred and fifty the art world of the twenty thousand works that the Nazis eventually confiscated from Ger- man institutions and collections. Many The anti-MOdERNisTs were subsequently burned; others were sold abroad, for hard currency. Wall texts Why the Third Reich targeted artists. noted the prices that public museums had paid for the works with “the taxes of the BY PETER sCHjEldAHl German working people,” and derided the art as mentally and morally diseased or as a “revelation of the Jewish racial soul.” Only a handful of the artists were Jews, but that made scant difference to a regime that could detect Semitic conta- gion anywhere. Some months earlier, Jo- seph Goebbels, the propaganda minister, had announced a ban on art criticism, as “a legacy of the Jewish influence.” “Degenerate Art” was a blockbuster, far outdrawing a show that had opened the day before, a short walk away, in a new edifice, dear to Hitler, called the House of German Art. “The Great German Art Exhibition” had been planned to demonstrate a triumphant new spirit in the nation’s high culture, but the preponderance of academic hackery in the work produced for it came as a rankling disappointment to Hitler, whose taste was blinkered but not blind. By official count, more than two million visitors thronged “Degen- erate Art” during its four-month run in Munich. Little is recorded of what they thought, but the American critic A. I. Philpot remarked, in the Boston Globe, that “there are probably plenty of people—art lovers—in Boston who will side with Hitler in this particular purge.” Germany had no monopoly on ou might not expect much drama the works. -

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin In the 1920s, Berlin was a hub for the transfer of culture between East- ern Europe, Paris, and New York. The German capital hosted Jewish art- ists from Poland, Russia, and Ukraine, where the Kultur-Liga was found- ed in 1918, but forced into line by Soviet authorities in 1924. Among these artists were figures such as Nathan Altman, Henryk Berlewi, El Lissitzky, Marc Chagall, and Issachar Ber Ryback. Once here, they be- came representatives of Modernism. At the same time, they made origi- nal contributions to the Jewish renaissance. Their creations left indelible traces on Europe’s artistic landscape. But the idea of tracing the curiously subtle interaction that exists between the concepts “Jewish” and “mod- ern”... does not seem to me completely unappealing and pointless, especially since the Jews are usually consid- ered adherents of tradition, rigid views, and convention. Arthur Silbergleit1 The work of East European Jewish artists in Germany is closely linked to the question of modernity. The search for new possibilities of expression was especially relevant just before the First World War and throughout the Weimar Republic. Many Jewish artists from Eastern Europe passed through Berlin or took up residence there. One distinguish- ing characteristic of these artists was that on the one hand they were familiar with tradi- tional Jewish forms of life due to their origins; on the other hand, however, they had often made a radical break with this tradition. Contemporary observers such as Kurt Hiller characterised “a modern Jew” at that time as “intellectual, future-oriented, and torn”.2 It was precisely this quality of being “torn” that made East European artists and intellectuals from Jewish backgrounds representative figures of modernity. -

Art from Europe and America, 1850-1950

Art from Europe and America, 1850-1950 Gallery 14 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 AM - 5 PM Sun 1 PM - 5 PM 2nd Fridays 10 AM – 9 PM Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Auguste Rodin French, 1840 – 1917 Head of Balzac, 1897 bronze Ackland Fund, 63.27.1 About the Art • Nothing is subtle about this small head of the French author Honoré de Balzac. The profile view shows a protruding brow, nose, and mouth, and the hair falls in heavy masses. • Auguste Rodin made this sculpture as part of a major commission for a monument to Balzac. He began working on the commission in 1891 and spent seven more years on it. Neither the head nor the body of Rodin’s sculpture conformed to critical or public expectations for a commemorative monument, including a realistic portrait likeness. Consequently, another artist ultimately got the commission. About the Artist 1840: Born November 12 in Paris 1854: Began training as an artist 1871-76: Worked in Belgium 1876: Traveled to Italy 1880: Worked for the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory; received the commission for one of his most famous works, monumental bronze doors called The Gates of Hell 1896: His nude sculpture of the French author Victor Hugo created a scandal 1897: Made the Ackland’s Head of Balzac 1898: Exhibited his monument to Balzac and created another scandal 1917: Died November 17 in Meudon 2 Edgar Degas French, 1834 – 1917 Spanish Dance, c. -

Modern Art and Politics in Prewar Germany

Stephanie Barron, “Modern Art and Politics in Prewar Germany,” in Barron (ed.), Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991): 9-23. In 1937 the National Socialists staged the most virulent attack ever mounted against modern art with the opening on July 19 in Munich of the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate art) exhibition, in which were brought together more than 650 important paintings, sculptures, prints, and books that had until a few weeks earlier been in the possession of thirty-two German public museum collections. The works were assembled for the purpose of clarifying for the German public by defamation and derision exactly what type of modern art was unacceptable to the Reich, and thus “un-German.” During the four months Entartete Kunst was on view in Munich it attracted more than two million visitors, over the next three years it traveled throughout Germany and Austria and was seen by nearly one million more On most days twenty thousand visitors passed through the exhibition, which was free of charge; records state that on one SundayAugust 2, 1937-thirty- six thousand people saw it.1 The popularity of Entartete Kunst has never been matched by any other exhibition of modern art. According to newspaper accounts, five times as many people visited Entartete Kunst as saw the Grosse Deutsche Kunstaussiellung (Great German art exhibition), an equally large presentation of Nazi-approved art that had opened on the preceding day to inaugurate Munich's Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German art), the first official building erected by the National Socialists. -

Bauhaus Houses and the Design Canon: 1923-2019

Bauhaus Houses and the Design Canon: 1923-2019 Jeremy Aynsley Introduction The focus of this paper is issues central to the reconstruction and display of iconic Modernist houses and how such issues complexify our understanding of the canonical reputation of the Bauhaus. Like the De Stijl movement, the Bauhaus can expect to receive much renewed media and scholarly attention as its centenary year of 2019 approaches. And like De Stijl, it holds pre-eminence in design history as a point when new theories and roles for design were realised by a remarkable set of actors. For its relatively short life of 14 years as a school in Germany, fol- lowed by the Chicago years, the Bauhaus has sustained what might be considered to be a disproportionate amount of attention. Indeed, arguably, its short life adds neatness to applying a narrative that suits re-telling and mythification. By applying the term ‘canon’ to design, we can assume this involves a select set of figures, objects and movements that claim official status, receiving scholarly atten- tion and entering museums and galleries. To do so, they conform to and meet certain criteria. As we know, critical theory, feminism, race theory and post-Marxism have all offered means of critique of the canon, questioning the basis on which it privileges certain histories – at worst, ‘dead white men’ or in the case of the Bauhaus, a site of high conservative modernism. Accordingly, in recent years, revisions in Bauhaus scholarship have also taken place, whether through questioning gender relations and roles at the school, challenging fundamental principles such as functionalism and universalism, or considering its diaspora of influence in a post-colonial context.1 Before turning to the houses of my focus today, it is perhaps worth teasing out the structures that have been central for the construction of the Bauhaus within the design historical canon: 1 Examples include Philipp Ostwalt (ed.), Bauhaus Conficts, 1919-2009: Controversies and Counterparts, Ostfildern (Hatje Cantz) 2009 and Bauhaus.