Bauhaus Houses and the Design Canon: 1923-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

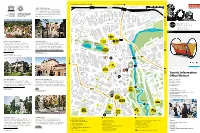

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

Ragioni E Sentimenti

RAGIONI E SENTIMENTI a cura di MARINA D’AMATO 2016 Università degli Studi Roma Tre Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione RAGIONI E SENTIMENTI a cura di MARINA D’AMATO 2016 Desidero ringraziare tutti coloro che hanno contribuito con la loro disponibilità e professionalità a quest’opera, in modi diversi, ma tutti indispensabili: Katiuscia Carnà, Francesca Cubeddu, Milena Gammaitoni, Valentina Punzo e, in particolare, Edmondo Grassi che, quotidianamente, ha tenuto i contatti con gli autori e ha effettuato l’editing complessivo dell’opera. “A Gregorio” Coordinamento editoriale: Gruppo di Lavoro Edizioni: © Roma, dicembre 2016 ISBN: 978-88-97524-90-8 http://romatrepress.uniroma3.it Quest’opera è assoggettata alla disciplina Creative Commons attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) che impone l’attribuzione della paternità dell’opera, proibisce di alterarla, trasformarla o usarla per produrre un’altra opera, e ne esclude l’uso per ricavarne un profitto commerciale. Immagine di copertina: Federico Marcoaldi, Alla ricerca dell’azzurro (2015). Indice MARINA D’AMATO, Introduzione 5 PER UNA TEORIA DEI SENTIMENTI MONIQUE HIRSCHHORN, Quelle place pour l’affectivité en sociologie? 23 MARC-HENRY SOULET, La compassion: un faux ami pour l’analyse sociologique 33 VITTORIO COTESTA, Le Muse di Max Weber 47 ANNA DE STEFANO PERROTTA, Sorokin e i sentimenti dimenticati 65 BERNARDO CATTARINUSSI, Le espressioni dell’eudemonia 75 ADELE BIANCO, Ragioni e regole – sentimenti e capacità. L’attualità di un dualismo costante e problematico nella storia -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

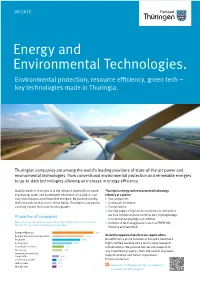

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

Bauhaus Centenary Year May Be Over, but the Influential Art and Design Movement Remains in the International Spotlight

Dear Journalist/Editor The Bauhaus centenary year may be over, but the influential art and design movement remains in the international spotlight. Below is an article that in- cludes comments from eminent publications, pointing out that 2019 was a cat- alyst for a new appreciation of the Bauhaus movement. And that interest con- tinues in 2020. Inspired by exhibitions both in Germany and around the world, more and more visitors are planning vacations in BauhausLand, the German federal states of Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. This editorial contribution is, of course, free for use. Bauhaus: Still in the spotlight! BAUHAUSLAND: ATTRACTING NEW FANS In 2019, the worldwide celebrations for the centenary of the Bauhaus focused on the achievements of this influential art and design movement. The range of exhibitions appealed to aficionados, but they also attracted a brand-new audi- ence. Leila Stone wrote in The Architect’s Newspaper: “Bauhaus is architec- ture. Bauhaus is costume design. Bauhaus is textile design. Bauhaus is furni- ture…it has never been more clear that Bauhaus is everywhere.” With appre- ciation increasing, more and more fans are planning to visit BauhausLand www.gobauhaus.com to spend their 2020 vacations in the German federal states of Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. BAUHAUSLAND: THE HOT DESTINATION FOR 2020 GQ Magazine trumpeted the headline: “Why travel trendsetters are heading for the birthplace of Bauhaus.” The list of ‘must dos’ includes the striking new Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, where the ‘must sees’ range from Josef Albers’ ground-breaking Nesting Tables to Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s Glass Table Lamp, which is still manufactured today! As for Architectural Digest, it names the brand-new Bauhaus Museum Dessau as one of its “Top 20 Places to Travel in 2020,” adding that “If you decide to go on a Bauhaus-themed pilgrimage, be sure to visit the Meisterhäuser, a group of white cubist homes where Gropius, Kandinsky, and other Bauhaus luminaries lived.” TourComm Germany Olbrichtstr. -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

The Analysis of the Influence and Inspiration of the Bauhaus on Contemporary Design and Education

Engineering, 2013, 5, 323-328 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/eng.2013.54044 Published Online April 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/eng) The Analysis of the Influence and Inspiration of the Bauhaus on Contemporary Design and Education Wenwen Chen1*, Zhuozuo He2 1Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, China 2Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China Email: *[email protected] Received October 11, 2012; revised February 24, 2013; accepted March 2, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Wenwen Chen, Zhuozuo He. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The Bauhaus, one of the most prestigious colleges of fine arts, was founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. Although it is closed in the last century, its influence is still manifested in design industries now and will continue to spread its principles to designers and artists. Even, it has a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, fashion design and design education. Up until now, Bauhaus ideal has al- ways been a controversial focus that plays a crucial role in the field of design. Not only emphasizing function but also reflecting the human-oriented idea could be the greatest progress on modern design and manufacturing. Even more, harmonizing the relationship between nature and human is the ultimate goal for all the designers to create their artworks. This essay will analyze Bauhaus’s influence on modern design and manufacturing in terms of technology, architecture and design education. -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

Press Information 100 Years of Bauhaus at ITB Anniversary Events

Press Information 100 years of bauhaus at ITB Anniversary events in Germany NOTE that many of these projects are still in the development stage Bauhaus Association 2019 1 Press Release 100 years of Bauhaus in Berlin Berlin, 6 March 2019 The year 2019 is dedicated to Bauhaus. Throughout Germany, numerous players are inviting visitors to the big anniversary under the auspices of the Bauhaus Association. Berlin is also celebrating the Bauhaus centenary with a large number of events. visitBerlin is taking the Bauhaus anniversary as an opportunity to present the Grand Tour of Berlin Modernism at this year's ITB (international travel trade show) in a special area (hall 12, stand 101). Totalling some 50 sites dotted around the city, visitors are invited to experience the entire panorama of Berlin's architectural modernity across all 12 districts. Fascinating information about the history of Bauhaus and the most important architects of the era have been brought together here. The diversity of the buildings presented ranges from the past to the present: from the six large housing estates from the 1920s to the Jewish Museum of 2001. The Grand Tour of Berlin Modernism can be found on the official website visitBerlin.de. 12 stories about Berlin Modernism can also be experienced on site with the ABOUT BERLIN app. In cooperation with the Bauhaus Archive and the Royal Porcelain Factory, Berlin (KPM), visitBerlin will also present legendary design objects by Bauhaus designers at its exhibition stand. On display, among other things, will be bowls by Marianne Brandt, the famous lamp by Wilhelm Wagenfeld and an exclusive preview of the new b100 Service Edition by KPM.