The Taxing and Spending Powers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

War Powers for the 21St Century: the Constitutional Perspective

WAR POWERS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: THE CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2008 Serial No. 110–164 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–756PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:32 May 14, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\IOHRO\041008\41756.000 Hintrel1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOWARD L. BERMAN, California, Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey Samoa DAN BURTON, Indiana DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. -

An Overview of My Internship with Congressman David Skaggs and How This Set a Course for My Career in Political Campaigning

Erin Ainsworth Fish Summer 2016 Independent Study Course An overview of my internship with Congressman David Skaggs and how this set a course for my career in political campaigning. By my senior year at CU I had changed my major twice and had gone from dreaming of a career as a journalist and traveling the world working for National Geographic, to serving in the Peace Corp and teaching English in West Africa. I was all over the map as far as picking out a career for myself and couldn’t hone in on one area of interest. I excelled in foreign languages and history but there didn’t seem to be a job which I could envision in those areas and my father wasn’t too subtle about what he’d like me to pursue by sending me articles on beginning salaries for lawyers. He was a maritime lawyer and felt that the law was a perfect career. I had settled on a major in Political Science as I had always been interested in government and my mother was particularly active in local politics. She had a heavy influence on my knowledge of current affairs and our dinner conversations were about the war in Iran and the Ayatollah Khomeini, the Civil Rights movement which she was passionate about, or we’d discuss the Kennedy assassinations and what that meant to her generation. Politics and American Government felt familiar to me and it seemed like a natural progression to major in political science. However I knew I didn’t want to pursue a career in the law and yet nothing stood out as an “aha!” job for me and with that came a constant level of anxiety. -

3:18−Cv−02279−RS

Case: 3:18-cv-2279 As of: 11/23/2019 09:39 AM PST 1 of 43 ADRMOP,CLOSED,RELATE U.S. District Court California Northern District (San Francisco) CIVIL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 3:18−cv−02279−RS City Of San Jose et al v. Ross et al Date Filed: 04/17/2018 Assigned to: Judge Richard Seeborg Date Terminated: 03/13/2019 Demand: $0 Jury Demand: None Relate Case Case: 3:18−cv−01865−RS Nature of Suit: 899 Other Statutes: Case in other court: 19−15457 Administrative Procedures Act/Review or Cause: 05:702 Administrative Procedure Act Appeal of Agency Decision Jurisdiction: U.S. Government Defendant Plaintiff City Of San Jose represented by John Frederick Libby Manatt Phelps and Phillips 11355 West Olympic Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90064−1614 (310) 312−4000 Fax: (310) 312−4224 Email: [email protected] LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Andrew Claude Case Manatt, Phelps, and Phillips 7 Times Square New York, NY 10036 212−790−4501 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Dorian Lawrence Spence Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law 1401 New York Avenue NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 662−8324 Fax: (202) 783−0857 Email: [email protected] PRO HAC VICE ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Emil Petrossian Manatt Phelps & Phillips LLP 11355 West Olympic Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90064 (310) 312−4294 Fax: (310) 312−4224 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Ezra D Rosenberg Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law 1500 K Street, NW Suite 900 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 662−8345 Fax: (202) 783−0857 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Case: 3:18-cv-2279 As of: 11/23/2019 09:39 AM PST 2 of 43 John W. -

Grand Ballroom West)

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu GOPAC SEMI-ANNUAL MEETING Wednesday, November 19 2:00 p.m. Sheraton Grand Hotel (Grand Ballroom West) You are scheduled to address the GOPAC meeting at 2:00 p.m. Lynn Byrd of GOPAC will meet you at the Sheraton Grand's front entrance and escort you to the Grand Ballroom West. You will be introduced by Newt Gingrich and your speech, including Q&A, should last no more than 25 minutes. The theme of the meeting is "a time to look back, a time to look forward" and GOPAC asks that you give an analysis of the elections and what the results mean to the Republican party and the country. (Attached is information on the Senate, House, Governor, and State Legislature elections.) There will be about 75-100 people (GOPAC Charter Members and guests) in the audience; no press or media has been invited. Speeches by Alexander Haig, Frank Fahrenkopf, Governor du Pont, Jack Kemp, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and Governor Kean will precede your remarks; Pat Robertson and Donald Rumsfeld are scheduled to speak after you. Expected to be in attendance at your luncheon speech are: Congressmen Dick Cheney, Joe DioGuardi, Robert Lagomarsino, and Tom Loeffler. Author Tom Clancy (Hunt for Red October/Red Storm Rising) is also expected to attend. GOPAC Background GOPAC was formed in 1978 and its purpose is to raise funds to elect state and local Republicans nationwide. This meeting is for Charter Members, who give or raise $10,000 a year for GOPAC. -

Chapter Five

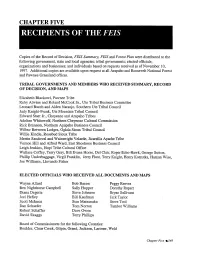

CHAPTER FIVE Copies of the Record of Decision, FEZS Summary, FEIS and Forest PEan were distributed to the following government, state and local agencies; tribal governments; elected officials; organizations and businesses; and individuals based on requests received as of November 10, 1997. Additional copies are available upon request at all Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forest and Pawnee Grassland offices. TRIBAL GOVERNMENTS AND MEMBERS WHO RECEIVED SUMMARY, RECORD OF DECISION, AND MAPS Elizabeth Blackowl, Pawnee Tribe Ruby Atwine and Roland McCook Sr., Ute Tribal Business Committee Leonard Burch and Alden Naranjo, Southern Ute Tribal Council Judy Knight-Frank, Ute Mountain Tribal Council Edward Starr Jr., Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Adeline Whitewolf, Northern Cheyenne Cultural Commission Rick Brannon, Northern Apapaho Business Council Wilbur Between Lodges, Oglala Sioux Tribal Council Willie Kindle, Rosebud Sioux Tribe Mertin Sandoval and Wainwright Velarde, Jicarrilla Apache Tribe Vernon Hill and Alfred Ward, East Shoshone Business Council Leigh Jenkins, Hopi Tribe Cultural Office Wallace Coffey, Terry Gray, Bill Evans Horse, Del Clair, Roger Echo-Hawk, George Sutton, Phillip Underbaggage, Virgil Franklin, Jerry Flute, Terry Knight, Henry Kotzutka, Haman Wise, Joe Williams, Llevando Fisher ELECTED OFFICIALS WHO RECEIVED ALL DOCUMENTS AND MAPS Wayne Allard Bob Bacon Peggy Reeves Ben Nighthorse Campbell Sally Hopper Dorothy Rupert Diana Degette Steve Johnson Bryan Sullivant Joel Hefley Bill Kaufman Jack Taylor Scott McInnis Stan Matsunaka -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2021 No. 163 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was To these iconic images, history has school sweetheart, 4.1 GPA at Oakmont called to order by the Speaker pro tem- now added another: that of a young High School, ‘‘one pretty badass ma- pore (Mrs. DEMINGS). marine sergeant in full combat gear rine,’’ as her sister put it. She could f cradling a helpless infant in her arms have done anything she wanted, and amidst the unfolding chaos and peril in what she wanted most was to serve her DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO the besieged Kabul Airport and pro- country and to serve humanity. TEMPORE claiming: ‘‘I love my job.’’ Who else but a guardian angel amidst The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The entire story of the war in Af- the chaos and violence of those last fore the House the following commu- ghanistan is told in this picture: the days in Kabul could look beyond all nication from the Speaker: sacrifices borne by young Americans that and look into the eyes of an infant WASHINGTON, DC, who volunteered to protect their coun- and proclaim: ‘‘I love my job’’? September 21, 2021. try from international terrorism, the Speaking of the fallen heroes of past I hereby appoint the Honorable VAL BUT- heroism of those who serve their coun- wars, James Michener asked the haunt- LER DEMINGS to act as Speaker pro tempore try even when their country failed ing question: Where do we get such on this day. -

Download Them

Credit: The Brown Palace Hotel, Denver Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education Commission Meeting November 7-8, 2019 Denver, Colorado Key Issues in Higher Education: A Look Around the Corner WICHE Commission Meeting – November 7-8, 2019 The Brown Palace Hotel, Denver, Colorado Schedule and Meeting Agenda Wednesday, November 6, 2019 Noon Optional Lunch for New WICHE Commissioners and Staff Gold 1:00 - 4:00 p.m. New Commissioner Orientation Tabor and Stratton 5:00 - 6:15 p.m. WICHE/WCET Reception Palace Arms Restaurant New WICHE commissioners, WICHE officers, and interested WICHE commissioners are invited to join the WCET Executive Council and Steering Committee for a networking reception. 6:30 p.m. Dinner for New WICHE Commissioners Earl’s Kitchen and Bar Please meet in the hotel lobby for a short walk to the restaurant. Thursday, November 7, 2019 7:45 a.m. Full Breakfast Available for Commissioners, Staff, and Guests Brown Palace Club 8:30 - 9:15 a.m. [Tab 1] Executive Committee Meeting (Open and Closed Sessions) 1-1 Tabor and Stratton Agenda (Open) Approval of the September 19, 2019, ACTION ITEM Executive Committee teleconference minutes 1-3 Discussion Items: Overview of the November 2019 Commission meeting schedule Update on State Acknowledgement that WICHE is an agency of the States Priority issues for the FY 2021 Workplan Other business Agenda (Closed) Discussion Item: Informal review of president’s performance and travel schedule 1-10 Denver, Colorado 1 9:30 - 10:15 a.m. [Tab 2] Committee of the Whole—Call to Order 2-1 Grand Ballroom Agenda Call to order: Senator Ray Holmberg, WICHE chair Land Acknowledgement: Ernest House, Jr., senior policy director, Keystone Policy Center and enrolled member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe in Towaoc, Colo. -

Republicans Honor Senator Bob Dole

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Republicans Honor Senator Bob/ Dole October IS, 1993 Hyatt Regency, Denver Tech Center Page 1 of 17 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu DINNER PROGRAM Welcome Master of Ceremonies Don Bain Chairman A Special Introduction Don Bain Colorado Republican Party Republican Party Chairman It is with great pride that I welcome the Honorable Senator Bob Dole to Colorado. As the Senate Republican Leader, Bob Dole is providing the direction Republicans need for a successful future. His leadership serves as an inspiration to all of us and continues to unite and strengthen our Party. Long Term Ideas A Short Term Couple While Senator Dole is providing leadership for the nation, The Colorado· Republican Party is continuing its efforts to build a strong political base of leadership for this state. Our Party is on a solid foundation of principles and ideas and it is through your support that we can continue to achieve our goals. Your hard work and dedication is greatly appreciated. With your continued Invocation Hank Brown support, we will achieve victory in 1994! United States Senator Video Introduction Featuring Bob Dole Introduction of Guest Speaker Philip Anschutz Guest of Honor Bob Dole From the Centennial state to the Greetings! As we begin our Senate Republican Leader Sunflower state - welcome to the efforts for a successful election year, 1993 Republican Fall Dinner! we are privileged to hear one of our Each of you will make a Party's great enunciators of difference in the months ahead. -

State Election Results, 1993

STATE OF COLORADO TRACT OF VOTES CAST 1993-1994 EMBER ODD-YEAR ELECTION November 2, 1993 PRIMARY ELECTION August 9, 1994 GENERAL ELECTION November 8, 1994 Published by VICTORIA BUCKLEY Secretary of State To: Citizens of Colorado From: Victoria Buckley, Secretary of State Subject: 1993-1994 Abstract of Votes I am honored to present you with this official publication of the 1993-1994 Abstract of Votes Cast. The information compiled in this summary is from material filed in my office by the county clerk and recorders. This publication will assist in the profiling of voting patterns of Colorado voters during the 1993 odd-year election and the 1994 primary and general elections. Therefore, I commemorate this abstract to those who practice their rights as Colorado citizens pursuant to the Constitution of Colorado. Article IT, Section 5, of the Colorado Constitution states: Elections and Licensing Division "All elections shall be free and open; and no power, Office of the Secretary of State civil or military, shall at any time interfere to 1560 Broadway, Suite 200 prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage. " Denver, Colorado 80202 Phone (303) 894-2680 Victoria Buckley, Secretary of State Willliam A. Hobbs, Elections Officer PRICE $10.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Glossary of Abstract Terms . 1 Research Assistance . 3 Directory of Elected and Appointed Officials Federal and State Officers . 4 State Senate . 5 State House of Representatives . ·. 8 District Attorneys . 12 Supreme Court Justices . 13 Court of Appeals Judges . 13 District Judges . 13 Judicial District Administrators . 17 Moffat Tunnel Commission and RTD Board of Directors ... -

1234 Massachusetts Avenue, NW • Suite 103 • Washington, DC 20005 • 202-347-1234

1234 Massachusetts Avenue, NW • Suite 103 • Washington, DC 20005 • 202-347-1234 #100-33 Information Alert: October 11, 1988 Medicaid Reform House Hearing TO: DD Council Executive Directors FROM: Susan Ames-Zierman On September 30, 1988, Congressman Henry Waxroan held a hearing on his bill, H.R.5233, and that of Congressman Florio, H.R. 3454, which is the House companion bill to Senator Chafee's S. 1673, the Medicaid Home and Community Quality Services Act. Mr. Waxman's opening statement is enclosed. Attached is testimony given by Congressman Steve Bartlett of Texas, Senator Chafee, and the Congressional Budget Office. Also enclosed is a side-by-side comparison of the two bills and current Medicaid law developed by the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress.. Senator Bentsen has agreed to mark up Senator Chafee's bill early in the 101st Congress. Should Senator Bentsen become the Vice-President, Senator Matsunaga of Hawaii would become Senate Finance Committee Chairman and would, in all likelihood, be agreeable to moving forward. Congressman Waxman, while not going as far as to discuss mark-up on either his or Florio's bill, did agree, in both his opening and closing statements, to work with Congressman Florio on a compromise early in the next Congress. A list of current co-sponsors of the Chafee/Florio bills is attached. We need to keep all those returning Senators and Congressman on-board when this process begins anew in January. For those in your Congressional delegations who are not current co-sponsors, plan some visits to programs while they are home campaigning this fall and over the holidays. -

DAVID E. SKAGGS. Born 1943. TRANSCRIPT of OH 1704V This Interview Was Recorded on January 27, 2011, for the Maria Rogers Oral Hi

DAVID E. SKAGGS. Born 1943. TRANSCRIPT of OH 1704V This interview was recorded on January 27, 2011, for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program. The interviewer is Brandon Springer. The interview also is available in video format, filmed by Emily Shuster. The interview was transcribed by Diane Baron. ABSTRACT: David Skaggs describes his own history leading up to becoming a member of the House of Representatives and some of the work he's been involved with since leaving public office. In the heart of the interview, he focuses on his interactions with Bill Cohen and Boulder Action for Soviet Jewry as well as his involvement with the Aleksandr Nikitin case, a Russian trial in which he participated as a member of the House of Representatives. NOTE: The interviewer’s questions and comments appear in parentheses. Added material appears in brackets. [A]. 00:00 (Today is Thursday, January 27th, and my name is Brandon Springer. I'm interviewing David Skaggs, who is a former congressman who helped Boulder Action for Soviet Jewry advocate their cause internationally—as well as many, many other things. This interview is being recorded for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program and is being filmed by Emily Shuster. So, David, my first question is when and where were you born?) February 22nd, 1943, in Cincinnati, Ohio, but we were living in Kentucky across the river at the time. (So, could you briefly tell us how you grew up and when you eventually came to Boulder, Colorado?) My family moved to the New York area when I was a little boy, baby really, and I grew up in and around New York City—briefly in Queens, New York, then for all of my schooling years in Cranford, New Jersey about 20 miles outside the city.