CHAPTER ONE PRECURSORS of the PASI ORGAN It Is Possible To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This

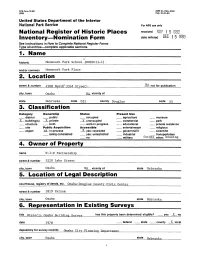

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUM - C 2005 I Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Race additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets {NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name Dundee/Happy Hollow Historic District___________________________________ Other names/site number 2. Location Roughly Hamilton on N, JE George & Happy Hollow on W, Street & number Leavenworth on S, 48th on E Not for publication [ ] City or town Omaha Vicinity [] State Nebraska Code NE County Douglas Code 055 Zip code 68132 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination Q request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [x] meets Q does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Fiscal Year 2017-2018

FISCAL YEAR 2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT mission Essential Pregnancy Services (EPS) is dedicated to helping expectant women and parenting families make life-affirming choices for themselves and their children through medical services, education, professional counseling, mate- rial assistance and resource information. BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Larry Roland services Lisa Wellendorf Past President EPS provides services at no cost, including: pregnancy testing, ultrasounds, Secretary Dan McMahon Treasurer Mike Draper STI screening and treatment, professional counseling, parenting classes Kevin Flint in English and Spanish, material assistance (including access to boutiques Amy Foje carrying maternity and baby essentials at two EPS locations) and resource Bob Goldsmith information on medical care, maternity housing, food, and more. Mike Maskek Missi Schembari, APRN, CPNP Dr. Nick Steinauer, MD Doug Wilwerding Executive Director Brad Burks AUXILIARY LEADERSHIP President Vicki Sempek Secretary Ann McGill Treasurer Diane McGill STAFF EXECUTIVE TEAM Theresa Alarcon Director of Nursing Patrick Flanery Director of Finance & Administration Connie MacBride Director of Client & Volunteer Services EPS CENTER LOCATIONS Benson | Maple Village | Bellevue eps baby layla empowering women educating families saving lives Empowering women is our top Educational programs at EPS are The life-saving care provided by priority. We believe that a woman diverse and designed to engage EPS is possible because of the can make a life-affirming choice women in growth opportunities that support of a community committed when she is provided resources help them develop the skills needed to protecting and nurturing the and opportunities to recognize her to attain individual and family self- lives of both mother and child. strengths, see possibilities and grow sufficiency. -

Yearbook American Churches

1941 EDITION YEARBOOK s of AMERICAN CHURCHES (FIFTEENTH ISSUE) (BIENNIAL) Edited By BENSON Y. LANDIS Under the Auspices of the FEDERAL COUNCIL OF THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN AMERICA Published by YEARBOOK OF AMERICAN CHURCHES PRESS F. C. VIGUERIE, (Publisher) 37-41 85TH ST., JACKSON HEIGHTS, N. Y. PREVIOUS ISSUES Year of Publication Title Editor 1916 Federal Council Yearbook .............. H. K. Carroll 1917 Yearbook of the Churches................H. K. Carroll • . 1918 Yearbook of the Churches................C. F. Armitage 1919 Yearbook of the Churches................C. F. Armitage 1920 Yearbook of the Churches.............. S. R. Warburton 1922 Yearbook of the Churches................E. O. Watson 1923 Yearbook of the Churches............... E. O. Watson 1925 Yearbook of the Churches............... E. O. Watson 1927 The Handbook of the Churches....... B. S. Winchester 1931 The New Handbook of the Churches .. Charles Stelzle 1933 Yearbook of American Churches........ H. C. Weber 1935 Yearbook of American Churches.........H. C. Weber 1937 Yearbook of American Churches.........H. C. Weber 1939 Yearbook of American Churches.........H. C. Weber Printed in the United States of America COPYRIGHT, 1941, BY SAMUELWUEL McCREA CAVERTCAVEf All rights reserved H CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................... iv I. The Calendar for the Christian Years 1941 and 1942 .................... v A Table of Dates A h e a d ....................................................... x II. Directories 1. Religious -

ED269866.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 269 866 EA 018 406 AUTHOR Yeager, Robert J., Comp. TITLE Directory of Development. INSTITUTION National Catholic Educational Association, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 34p. AVAILABLE FROMPublication Sales, National Catholic Educational Association, 1077 30th Street, N.W., Suite 100, Washington, DC 20007-3852 ($10.95 prepaid). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administra"orsi 4.Catholic Schools; Elementary Secondary ,ducatien; *Institutional Advancement; National Surveys; Postsecondary Education IDENTIFIERS Development Officers ABSTRACT This booklet provides a listing of all the Catholic educational institutions that responded to a nationalsurvey of existing insti utional development provams. No attemptwas made to determine the quality of the programs. The information is providedon a regional basis so that development personnel can mo.s readily make contact with their peers. The institutions are listed alphabetically within each state grouping, and each state is listed alphabetically within the six regions of the country. Listingsare also provided for schools in Belgium, Canada, Guam, Italy, and Puerto Rico. (PGD) *********************************.************************************* * Reproductions supplied by =DRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ***********************0*****************************************1***** £11 Produced by The Office of Development National Catholic Education Association Compiled by -

Plans Detailed for April 2 3 Episcopal Ordination Listen to Protest

THE DENVER ARCHDIOCESANA EDITION THURSDAY, APRIL 17, 1949 VOL Plans Detailed for April 2 3 Episcopal Ordination By E. Chris Hernon his duties. After which, the chief conse crator invites all present to pray, while On April 23, 1969, Bishop-Designate George R. Evans will be raised to the the bishop-elect prostrates himself and episcopacy as Auxiliary Bishop of the Denver Archdiocese, by the Apostolic the cantors sing the litany of the Saints. Delegate to the United States, Archbishop Luigi Raimondi, as principal con- The bishop-elect then kneels before the secrator, assisted by Archbishop James V. Casey of Denver, and Bishop Hub principal consecrator, and the consecrat ing bishops in turn lay their hands upon ert M. Newell of Cheyenne, co-consecrators, in the presence of 22 other Arch his head. bishops and Bishops, 19 o f whom will concelebrate with the new Bishop and his consecrators the Episcopal Mass of Ordination. TW O deacons hold the open book of the Gospels on the head of the bishop- The ceremonies will take place in the On Wednesday next, the consecrators. elect, while the prayer of consecration is Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception the bishop-elect and all concelebrants said. where Denver-born Bishop-Designate robed for Mass, will walk in procession The deacons remove the book of the Evans, 46. was ordained to the priesthood from the Cathedral entrance to the altar, Gospels, and the principal consecrator by Archbishop Urban J. Vehr, May 31, where the Roman Pontifical, copies of the puts on the linen gremial, takes the 1947. -

Conversatio06.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURES Many Hats One Mission: Father Matthew Luft ’02 7 Sister Mary Anthony Wagner, OSB, Award 12 ABOUT THE COVER Ezekiel Prophet of Hope Award 13 Youth in Theology and Ministry Program (YTM) counselors Former SOT•Sem student receives $100,000 and youth enjoy the afternoon for award-winning essay 17 sun on the shores of Saint John's Lake Sagatagan. YTM is for high school age Catholic DEPARTMENTS leadership youth who have had positive experiences of Church Dean’s Message 3 and want to gather with other like minded youth and adults Abbot’s Message 4 to explore faith, leadership and vocation. News 5 This program engages the adult Alumni Profile 6 mentors, who work in parish ministry, in a Masters of Arts Graduates 8 in Pastoral Ministry. Board Profile: John Boyle 10 To learn more about YTM, visit www.YTM-SJU.org. Book Review: Benedictine Daily Prayer 11 Faculty Profile: Father Kevin Seasoltz, OSB 16 Staff and Faculty Update 18 Development Message 21 Alumni Update 22 In Hope of Ressurection 23 Conversatio is published twice each year by the Development Office of Saint John’s School of Theology•Seminary. Dean Editor Contributing Writers Dr. William Cahoy Anna May Kampa Christy Arnold Dr. William Cahoy Director of Development Photography Brendon Duffy and External Relations Patricia Weishaar Abbot John Klassen, OSB William K. Marsella Joe Young, St. Cloud Visitor Mary Ewing Stamps For comments, questions or story ideas, contact: Anna May Kampa, Editor, Saint John’s School of Theology•Seminary, Collegeville, MN 56321; 320-363-3570 or email at [email protected]. -

ARCHBISHOP GERALD THOMAS BERGAN CATHOLIC SCHOOL -Est

ARCHBISHOP GERALD THOMAS BERGAN CATHOLIC SCHOOL -est. 1960 • As we recognize the 125th Birthday of Archbishop Gerald T. Bergan himself, we celebrate our Catholic School’s history while optimistically looking forward to our future. We recently have taken a deliberate look at our school logo and have made some subtle changes. OUR MASCOT • Since the creation of Saint Patrick’s High School in 1950, the Knight has been the chosen mascot to represent the Catholic High School in Fremont. As a ministry of St. Patrick’s Parish, the school colors of Kelly Green and Gold link to the Parish’s Irish Heritage. When Archbishop Bergan High School was completed in 1960, the new school adopted the Knight mascot and school colors from the former St. Patrick’s High School. What is a Knight? • We are proud to have the Knight as our school mascot as in the Middle Ages Knights were represented as warriors for God. In the 11th and 12th centuries, under the influence of the Catholic Church, a code of moral behavior called Chivalry developed that Knights were expected to uphold. A Knight took an oath to defend the Catholic Church, protect defenseless people, and treat their opponents with compassion and respect. This code held that Knights should only fight for glory and not material rewards and that all honor was given to God for all victories achieved. Chivalry and Blackletter • Today we honor this Code of Chivalry at Archbishop Bergan with the Knight’s C.O.D.E. Each letter of the word C.O.D.E. -

Czech Churches in Nebraska

CZECH CHURCHES IN NEBRASKA ČESKÉ KOSTELY V NEBRASCE (Picture) The picture on the cover of this book is of the first Czech Catholic church in Nebraska built in Abie 1876 Editor Vladimir Kucera 1974 CZECH CATHOLIC CHURCHES IN NEBRASKA Box Butte Co. Hemingford 18 Dodge Co. Dodge 63 Lawn 19 Douglas Co. St. Adalbert 67 Boyd Co. Lynch 20 Omaha St. Rose 67 Spencer 20 Assumption 68 Brown Co. Midvale 21 St. Wenceslas 71 Buffalo Co. Ravenna 21 Fillmore Co. Milligan 76 Schneider 22 Gage Co. Odell 79 Butler Co. Abie 16 Hayes Co. Tasov 82 Appleton 24 Howard Co. Farwell 84 Brainard 26 St. Paul 85 Bruno 29 Warsaw 86 Dwight 35 Knox Co. Verdigre 89 Linwood 39 Lancaster Co. Agnew 91 Loma 39 Saline Co. Crete 93 Cass Co. Plattsmouth 42 Tobias 98 Cedar Co. Menominee 44 Wilber 102 Cheyenne Co. Lodgepole 45 Saunders Co. Cedar Hill 111 Clay Co. Loucky 46 Colon 113 Fairfield 51 Morse Bluff 115 Colfax Co. Clarkson 53 Plasi 118 Dry Creek 55 Prague 124 Heun 55 Touhy 128 Howells 56 Valparaiso 129 Schuyler 57 Wahoo 131 Tabor 57 Weston 134 Wilson 59 Seward Co. Bee Curry 60 Sheridan Co. Hindera Cuming Co. Olean 61 Valley Co. Netolice 139 West Point 63 Ord 143 Saunders Co. Wahoo 151 Thurston Jan Hus 168 Weston 155 Maple Creek Bethlehem 169 Zion 156 Evangelical Congregation Colfax Co. New Zion 160 near Burwell 172 Douglas Co. Bohemian Fillmore Co. Milligan 173 Brethren 163 Douglas Co. Bethlehem 167 Central West Presbytery 174 (Picture) Ludvik Benedikt Kucera Biskup lincolnsky 1888 – 1957 Published by Nebraska Czechs Inc. -

Nomination Form Date Entered DEC I 5 I983 See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries Complete Applicable Sections______1

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No.1024-OO18 (3-82) Exp.10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received NQV ! 5 I983 Inventory Nomination Form date entered DEC i 5 I983 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections___________________________________ 1. Name V historic Monmouth Park School -(D009;ll-l) and/or common Monmouth Park Place 2. Location street & number 4508 Nor-tH^33rd Streef- not for publication city, town Omaha NA vicinity of state Nebraska code 031 county Douglas code 55 3,. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object NA in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military future othpr- housing 4. Owner of Property name N-J-D Partnership street & number 3120 Lake Street city, town Omaha NA vicinity of state Nebraska 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Qmaha-Douglas County Civic Center street & number 1819 Farnam city, town Omaha state Nebraska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic Omaha Building Survey has this property been determined eligible? __ yes X no date 1978 federal __ state __ county X local depository for survey records Qmaha City Planning Department city, town Omaha state Nebraska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site NA X good ruins X altered moved date . -

FAMILY HISTORIES Buckendahl; Stephanie, Christopher, and Nicholas Bradley; and Quentin, Aaron, Lane, and Cole Meyer

Nebraska. They had nine grandchildren: Chad and Brice FAMILY HISTORIES Buckendahl; Stephanie, Christopher, and Nicholas Bradley; and Quentin, Aaron, Lane, and Cole Meyer. Marjorie taught in District 38, south of Randolph and in Delbert and Marjorie Ahlman District 41, Wayne County; District 3 and in District 64 in Pierce County; and fifteen years in Pierce Public Schools Delbert Ahlman in grades three and four. After twenty-five years, she was born July 10, retired in August of 1983. Delbert was a retired farmer. 1917, at Pierce, Delbert and Marjorie enjoyed camping, traveling, and Nebraska, to Herman attending country music festivals. Marjorie passed away and Ida (Hitz) in March, 1987. Delbert moved to Randolph for a few Ahlman. He was years, but returned to Pierce before passing away in baptized in St. John's December, 2004. Revised and submitted by Sherry Lutheran church by Bradley Rev. Hilpert. On December 28, 1941, he was united Larry and Linda Alderson in marriage to Larry Alderson Marjorie Hausmann and his twin brother, by Rev. M.F. Scheips, Lyle, were born Pierce. Marjorie was February 2, 1946 in born November 3, Sioux City, Iowa to 1921, near Randolph, Robert and Irene Delbert and Marjorie Ahlman and was the daughter (Jordan) Alderson. of George and Rosa (Stueckrath) Hausmann. Marjorie Lyle passed away Hausmann was baptized by the Rev. William Jassman at three weeks later. Belden, Nebraska. She spent her teenage life in the Larry grew up in the Randolph area. Vernon, her brother, and six other Carroll and horseback riders from east and south of Randolph rode to Randolph area. -

N O R Th 24Th Str Eet W a Lk in G to Ur

presents the NORTH 24TH STREET WALKING TOUR STREET WALKING 24TH NORTH North 24th Street is pretty quiet these days. There is a little noise from the barbershops and retail outlets that dot the streetscape. A couple of restau- rants are making a go of it just off the thoroughfare on Lake Street. And there’s a burgeoning arts scene. But the music that once enlivened the area is mostly silent. For blacks who began to reside in North Omaha during the early 20th century, 24th Street became known as the “Street of Dreams.” The area around 24th and Lake Streets emerged as a lively district of music clubs, theaters, restau- rants and retail shops. It Members of the Marching was a haven for enter- Majorettes during a parade passing tainment from the 1920s the intersection of 24th and Lake through the 1960s. in the 1950s. Photo courtesy Great Plains Black History Museum. The street also was important to Jewish settlers, who began to populate the area in the 1890s. They called the stretch of North 24th Street from Cuming to Lake Streets the “Miracle Mile.” Jewish historian Arthur Grossman described the street as “the arterial lifeline connecting homes, shops, and sundry suppliers of products and services necessary for the maintenance of Jewish life.” Blacks, Jews and other ethnicities coexisted peacefully for decades. In 1914, there were 17 grocery stores, five tailors, seven shoe repair shops and five second-hand stores on that stretch of North 24th Street alone, along with confectioners, barbers and butchers. Within four years, 15 of the businesses in the area were owned by blacks, including five restaurants. -

Mexican Americans of South Omaha (1900-1980)

Religions and Community: Mexican Americans of South Omaha (1900-1980) Maria Arbalaez, Ph.D. Religion and Community: Mexican Americans of South Omaha (1900-1980) Maria Arbelaez, Ph.D. Office of Latino/Latin American Studies (OLLAS) Department of History University of Nebraska at Omaha Report prepared for the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies (OLLAS) University of Nebraska, at Omaha April 18, 2007 Acknowledgements I'd like to thank the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies (OLLAS) for their generous support of this study. Funding for this report and data collection for this project was provided in part by a grant to OLLAS from the U.S. Department of Education. I'd also like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Bruce Garver, Chair of the Department of History at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Cover photo courtesy of Mary Perez 3 OLLAS (the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies of the Great Plains) is a center of excel- lence that focuses on the Latino population of the Americas with particular emphasis on U.S. Latino and Latin American transnational communities. It is an interdisciplinary program that enhances our understanding of economic, political, and cultural issues relevant to these communities. In August 2003, OLLAS received a $1,000,000 award from the Department of Education (Award # P116Z030100). One of the three central objectives funded by this grant is the "Development and implementation of a research agenda designed to address the most urgent and neglected aspects associated with the region's unprecedented Latino population growth and its local, regional and transhemispheric implications.