The Journal of Agriculture of the University of Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

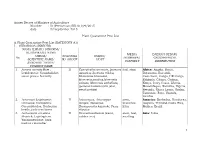

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Antirrhinum Majus

The EMBO Journal Vol.18 No.19 pp.5370–5379, 1999 Ternary complex formation between the MADS-box proteins SQUAMOSA, DEFICIENS and GLOBOSA is involved in the control of floral architecture in Antirrhinum majus Marcos Egea-Cortines1,2, Heinz Saedler and by the shoot apical meristem, which instead of maintaining Hans Sommer a vegetative fate, produces floral organs. This process is controlled by meristem identity genes that comprise in Max-Planck-Institut fu¨rZu¨chtungsforschung, Carl-von-Linne Weg 10, Antirrhinum FLORICAULA (FLO) (Coen et al., 1990), 50829 Ko¨ln, Germany SQUAMOSA (SQUA) (Huijser et al., 1992) and CENTRO- 1Present address: Department of Genetics, Escuela Tecnica Superior de RADIALIS (CEN) (Bradley et al., 1996). Squa plants, for Ingenieros Agro´nomos, Universidad Polite´cnica de Cartagena, instance, flower rarely because most meristems that should Paseo Alfonso XIII 22, 30203 Cartagena, Spain adopt a floral fate remain as inflorescences (Huijser et al., 2Corresponding author 1992). Once the flower meristem is established, several e-mail: [email protected] parallel events occur: first, organ initiation changes from a spiral to a whorled fashion; secondly, the developing In Antirrhinum, floral meristems are established by organs in the whorls adopt a specific identity; and thirdly, meristem identity genes. Floral meristems give rise to the floral meristem terminates. floral organs in whorls, with their identity established Floral organ identity in angiosperms seems to be con- by combinatorial activities of organ identity genes. trolled by three conserved genetic functions that act in a Double mutants of the floral meristem identity gene combinatorial manner (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991). -

Origin of Plant Originated from Some Had Possibly Changed Recognise Original Wild Species. Suggested a Relationship with Pr

The possible origin of Cucumis anguria L. by A.D.J. Meeuse (National Herbarium, Pretoria) (Issued Oct. 2nd, 1958) Cucumis India Gherkin” “Bur anguria L., the “West or Gherkin”, is a cultigen known to have occurred in the West Indies in a cultivated or more or less adventitious state since before 1650 when the first accounts of this plant were published (1, 2). The occurrence of a single species of this old world genus — which is mainly African but extends through South West Asia to India — in America, combined with the fact that it is almost exclusively found in cultivation or as an escape, makes one feel suspicious about its being truly indigenous in the New World. Naudin (4) discussed the history of this plant and suggested that it introduced from West Africa whence slaves were was originally negro brought to the New World. However, he admittedly did not know any wild African species of Cucumis which resembles C. anguria sufficiently to deserve consideration as its probable ancestor. J. D. Hooker (5) also discussed the origin of the West Indian plant and was inclined to agree that it originated from some wild African ancestral form which had possibly changed so much through cultivation that it would be somewhat difficult to recognise the original wild species. He suggested a relationship with Cucumis prophetarum and “C. figarei” but he cautiously stated that these two species are perennial, whereas C. anguria is a typical annual. A. de Candolle (6) pointed out that although C. anguria was generally assumed to be a native of the Antilles, more particularly of Jamaica, two facts plead against this idea. -

Differential Regulation of Symmetry Genes and the Evolution of Floral Morphologies

Differential regulation of symmetry genes and the evolution of floral morphologies Lena C. Hileman†, Elena M. Kramer, and David A. Baum‡ Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 16 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138 Communicated by John F. Doebley, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, September 5, 2003 (received for review July 16, 2003) Shifts in flower symmetry have occurred frequently during the patterns of growth occurring on either side of the midline (Fig. diversification of angiosperms, and it is thought that such shifts 1h). The two species of Mohavea have a floral morphology that play important roles in plant–pollinator interactions. In the model is highly divergent from Antirrhinum (3), resulting in its tradi- developmental system Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon), the tional segregation as a distinct genus. Mohavea corollas, espe- closely related genes CYCLOIDEA (CYC) and DICHOTOMA (DICH) cially those of M. confertiflora, are superficially radially symmet- are needed for the development of zygomorphic flowers and the rical (actinomorphic), mainly due to distal expansion of the determination of adaxial (dorsal) identity of floral organs, includ- corolla lobes (Fig. 1a) and a higher degree of internal petal ing adaxial stamen abortion and asymmetry of adaxial petals. symmetry relative to Antirrhinum (Fig. 1 a and g). During However, it is not known whether these genes played a role in the Mohavea flower development, the lateral stamens, in addition to divergence of species differing in flower morphology and pollina- the adaxial stamen, are aborted, resulting in just two stamens at tion mode. We compared A. majus with a close relative, Mohavea flower maturity (Fig. -

By W. G. D'arcy Issued by the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. 139 THE ISLAND OF ANEGADA AND ITS k'LORA by W. G. D'Arcy Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U. S. A. February 16, 1971 THE ISLAND OF ANEGADA AND ITS nORA The island of Anegada in the British Virgin Islands is of interest because of its isolated location in relation to the Antillean island arc, its unusual topography amongst the Virgin Islands, and also the fact that it has received very little scientific attention. It now seems destined to join the list of islands which have succumbed to modern "development". This checklist combines past published reports with the writer's own collections and attempts to correct the nomenclature formerly applied to this flora. THE ISLAND Anegada is the northeasternmost of the British Virgin Islands and of the entire West Indian arc for that matter, vying with the rocky lighthouse, Sombrero, well to the southeast, as the closest Antillean approach to Europe. Its geographic coordinates are 18'45'N and 64°20'W, and it encompasses 14.987 square miles (Klumb and Robbins 1960) or about 33 square km. In shape it is a rather lumpy crescent with its long axis running approximately west by north and east by south. The nearest land, Virgin Gorda, some thirteen miles (ca 22 km) to the south and slightly west, is a prominent feature on the horizon (Fig. I), as is the mass of the other Virgins--Tortola, Camanoe and Jost Van Dyke-- further to the southwest. To the north and east there is no land for a long way. -

Cucumis Anguria Var. Anguria Click on Images to Enlarge

Species information Abo ut Reso urces Hom e A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Cucumis anguria var. anguria Click on images to enlarge Family Cucurbitaceae Scientific Name Cucumis anguria L. var. anguria Flower and leaves. Copyright CSIRO Meeuse, A.D.J. (1958) Blumea Supplementary Series 4: 200. Common name West Indian Gherkin Weed * Fruit. Copyright K.R. McDonald Stem A slender trailing or climbing annual herb, all parts densely hispid; stems ribbed, to 3 m long x 4 mm diameter. Tendrils simple, clothed in hispid hairs; tendrils leaf-opposed. Leaves Leaf blades broadly ovate, cordate at base, deeply 3-5 lobed; blades about 35-95 x 40-90 mm, petioles about 15-60 mm long; both upper and lower leaf surfaces and the petioles densely clohted in hispid hairs. Flowers Inflorescences unisexual. Male flowers: solitary or borne in fascicles of 2-10 flowers, or in pedunculate Habit, leaves and fruit. Copyright K.R. McDonald groups; flowers about 8 mm diam; calyx tube (hypanthium) about 3-3.5 mm long, lobes linear about 0.5-2 mm long; corolla lobes ovate about 3.8-6 mm long, yellow; stamens 3, two stamens with 2-locular anthers and one stamen with a unilocular anther. Female flowers: solitary; pedicels 10-95 mm; ovary 7-9 mm long, bristly. Fruit Fruit ellipsoidal, 35-60 x 20-28 mm, densely and shortly prickly or warted, green with paler bands, ripening yellow; seeds 4-6 mm long. -

An Everlasting Pioneer: the Story of Antirrhinum Research

PERSPECTIVES 34. Lexer, C., Welch, M. E., Durphy, J. L. & Rieseberg, L. H. 62. Cooper, T. F., Rozen, D. E. & Lenski, R. E. Parallel und Forschung, the United States National Science Foundation Natural selection for salt tolerance quantitative trait loci changes in gene expression after 20,000 generations of and the Max-Planck Gesellschaft. M.E.F. was supported by (QTLs) in wild sunflower hybrids: implications for the origin evolution in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA National Science Foundation grants, which also supported the of Helianthus paradoxus, a diploid hybrid species. Mol. 100, 1072–1077 (2003). establishment of the evolutionary and ecological functional Ecol. 12, 1225–1235 (2003). 63. Elena, S. F. & Lenski, R. E. Microbial genetics: evolution genomics (EEFG) community. In lieu of a trans-Atlantic coin flip, 35. Peichel, C. et al. The genetic architecture of divergence experiments with microorganisms: the dynamics and the order of authorship was determined by random fluctuation in between threespine stickleback species. Nature 414, genetic bases of adaptation. Nature Rev. Genet. 4, the Euro/Dollar exchange rate. 901–905 (2001). 457–469 (2003). 36. Aparicio, S. et al. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and 64. Ideker, T., Galitski, T. & Hood, L. A new approach to analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science 297, decoding life. Annu. Rev. Genom. Human. Genet. 2, Online Links 1301–1310 (2002). 343–372 (2001). 37. Beldade, P., Brakefield, P. M. & Long, A. D. Contribution of 65. Wittbrodt, J., Shima, A. & Schartl, M. Medaka — a model Distal-less to quantitative variation in butterfly eyespots. organism from the far East. -

Optimization of Conditions for Callus Induction and Indirect Organogenesis of Cucumis Anguria L

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Asian Journal of Plant Science and Research, 2015, 5(11):53-61 ISSN : 2249-7412 CODEN (USA): AJPSKY Optimization of conditions for callus induction and indirect organogenesis of Cucumis anguria L. 1J. Jerome Jeyakumar * and 2L. Vivekanandan 1Department of Biotechnology, Pavendar Bharathidasan College of Arts & Science, Mathur, Pudukottai Road, Tiruchchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India 2Plant Physiology and Biotechnology Division, UPASI TRF, Tea Research Institute, Nirar Dam P.O., Valparai, Tamil Nadu, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT An efficient procedure has been developed for callus induction and indirect organogenesis of Cucumis anguria L. Seedlings were grown under in vitro conditions and selection was carried out between the leaf and nodal segments for the explants in the seedlings. Different parameters like the explant source, hormones and sugars were checked for the optimization of cultures. Leaf explants which showed the maximum response to callus induction (42.0%) was thus, selected for the study. MS medium supplemented with 4.0 mg L -1 2,4-D and 4.0 mg L -1 NAA proved to be the most efficient hormone in promoting callus development from the leaf explants with 42.0% response and was the most favorable medium. Apart from the type of explant and growth regulators, different sugars and their concentrations were also checked for the induction of callus. 3% glucose produced highest rate of callus in the culture. In response to MS medium with 3.0 mg L -1 BAP and 0.5 mg L -1 Kn, best response of shoot induction was evoked with an average number of 5.02±0.76 shoots per callus. -

Cucurbit Seed Production

CUCURBIT SEED PRODUCTION An organic seed production manual for seed growers in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern U.S. Copyright © 2005 by Jeffrey H. McCormack, Ph.D. Some rights reserved. See page 36 for distribution and licensing information. For updates and additional resources, visit www.savingourseeds.org For comments or suggestions contact: [email protected] For distribution information please contact: Cricket Rakita Jeff McCormack Carolina Farm Stewardship Association or Garden Medicinals and Culinaries www.carolinafarmstewards.org www.gardenmedicinals.com www.savingourseed.org www.savingourseeds.org P.O. Box 448, Pittsboro, NC 27312 P.O. Box 320, Earlysville, VA 22936 (919) 542-2402 (434) 964-9113 Funding for this project was provided by USDA-CREES (Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service) through Southern SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education). Copyright © 2005 by Jeff McCormack 1 Version 1.4 November 2, 2005 Cucurbit Seed Production TABLE OF CONTENTS Scope of this manual .............................................................................................. 2 Botanical classification of cucurbits .................................................................... 3 Squash ......................................................................................................................... 4 Cucumber ................................................................................................................... 15 Melon (Muskmelon) ................................................................................................. -

Growth and Flowering of Antirrhinum Majus L. Under Varying Temperatures

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY 1560–8530/2004/06–1–173–178 http://www.ijab.org Growth and Flowering of Antirrhinum majus L. under Varying Temperatures MUHAMMAD MUNIR1, MUHAMMAD JAMIL, JALAL-UD-DIN BALOCH AND KHALID REHMAN KHATTAK Faculty of Agriculture, Gomal University, D.I. Khan, Pakistan 1Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Plants of an early flowering cultivar ‘Chimes White’ of Antirrhinum were subjected to three temperature regimes (0, 10 and 20°C) at 6-leaf pair stage to observe their effects on the flowering time and plant quality. Plants at higher temperature (20°C) flowered earlier (86 days) than the lower ones i.e. 109 days (10°C) and 145 days (0°C). However, maximum flower numbers (33) were counted in plants at 10°C followed by 20°C (29). Plants at 0°C produced only seven flower buds. The quality of plants was improved at 10°C temperature; whereas, it was poor at 0°C. Key Words: Antirrhinum majus; Flowering; Temperature INTRODUCTION optimum temperatures were required, as photosynthesis was the dominant process (Miller, 1962). Temperature has a direct influence on the rate of many Flowering time in Antirrhinum was shown to be chemical reactions, including respiration that is the process controlled by adjusting night temperatures in relation to responsible for growth and development of plants and light intensity during the day. Earlier flowering resulted, photosynthesis. For most species, biological activity stops after adjusting night temperatures upward during the below 0°C and above 50°C, and proteins are irreversibly growing period after bright winter days. -

Redalyc.Phenolic Compound Production and Biological Activities from in Vitro Regenerated Plants of Gherkin ( Cucumis Anguria

Electronic Journal of Biotechnology E-ISSN: 0717-3458 [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Chile Thiruvengadam, Muthu; Chung, Ill-Min Phenolic compound production and biological activities from in vitro regenerated plants of gherkin ( Cucumis anguria L.) Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, vol. 18, núm. 4, 2015, pp. 295-301 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Valparaíso, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=173341112006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 18 (2015) 295–301 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Electronic Journal of Biotechnology Phenolic compound production and biological activities from in vitro regenerated plants of gherkin (Cucumis anguria L.) Muthu Thiruvengadam, Ill-Min Chung ⁎ Department of Applied Bioscience, College of Life and Environmental Science, Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea article info abstract Article history: Background: The effect of polyamines (PAs) along with cytokinins (TDZ and BAP) and auxin (IBA) was induced by Received 8 January 2015 the multiple shoot regeneration from leaf explants of gherkin (Cucumis anguria L.). The polyphenolic content, Accepted 2 May 2015 antioxidant and antibacterial potential were studied from in vitro regenerated and in vivo plants. Available online 30 May 2015 Results: Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 3% sucrose containing a combination of 3.0 μM TDZ, 1.0 μMIBAand75μM spermidine induced maximum number of shoots (45 shoots per explant) was Keywords: achieved. -

Snapdragon Rust, RPD No

report on RPD No. 635 PLANT July 1982 DEPARTMENT OF CROP SCIENCES DISEASE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN SNAPDRAGON RUST Rust caused by the fungus Puccinia antirrhini is one of the most widespread and damaging diseases of snap- dragon (Antirrhinum majus). This worldwide disease was first reported in Santa Cruz, California, in 1879. The first known instance of it in Illinois was at Lake Forest in 1912. A few of the related wild native species of Linaria (butter-and-eggs) and Cordylanthus (bird’s beak) are only slightly susceptible. Infection in snapdragons may develop rapidly, stunting the shoots and flower spikes. When severe, rusted plants Figure 1. Snapdragon rust. Note the “halos” around may wilt and die before or during flowering. During dry the rust pustule (courtesy G.W. Simone). weather, severely rusted leaves dry up and die. In warm humid regions the rust pustules are invaded by secondary fungi (principally species of Fusarium) that may kill the leaves and stems. Rust is most serious in cool humid climates and is checked by extended periods of hot, dry weather. Rust affects snapdragons of all ages, from seedlings and cuttings to mature plants, both in the field and in the greenhouse. Leaves become the most heavily infected, but young stems, petioles, flower (calyx) structures, and seed capsules often are also severely attacked. Leaves Figure 2. Close-up of rust on snapdragon leaves. that are heavily rusted wilt as though from lack of water. When flowers are infected, the ovaries are destroyed, reducing seed production. SYMPTOMS The first symptom is the presence of scattered, small yellow flecks, less than 1/16 (2 mm) in diameter, just under the epidermis on the undersides of the leaves.