Alfred and Margaret Rich of Gundaroo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sumo Has Landed in Regional NSW! May 2021

Sumo has landed in Regional NSW! May 2021 Sumo has expanded into over a thousand new suburbs! Postcode Suburb Distributor 2580 BANNABY Essential 2580 BANNISTER Essential 2580 BAW BAW Essential 2580 BOXERS CREEK Essential 2580 BRISBANE GROVE Essential 2580 BUNGONIA Essential 2580 CARRICK Essential 2580 CHATSBURY Essential 2580 CURRAWANG Essential 2580 CURRAWEELA Essential 2580 GOLSPIE Essential 2580 GOULBURN Essential 2580 GREENWICH PARK Essential 2580 GUNDARY Essential 2580 JERRONG Essential 2580 KINGSDALE Essential 2580 LAKE BATHURST Essential 2580 LOWER BORO Essential 2580 MAYFIELD Essential 2580 MIDDLE ARM Essential 2580 MOUNT FAIRY Essential 2580 MOUNT WERONG Essential 2580 MUMMEL Essential 2580 MYRTLEVILLE Essential 2580 OALLEN Essential 2580 PALING YARDS Essential 2580 PARKESBOURNE Essential 2580 POMEROY Essential ©2021 ACN Inc. All rights reserved ACN Pacific Pty Ltd ABN 85 108 535 708 www.acn.com PF-1271 13.05.2021 Page 1 of 31 Sumo has landed in Regional NSW! May 2021 2580 QUIALIGO Essential 2580 RICHLANDS Essential 2580 ROSLYN Essential 2580 RUN-O-WATERS Essential 2580 STONEQUARRY Essential 2580 TARAGO Essential 2580 TARALGA Essential 2580 TARLO Essential 2580 TIRRANNAVILLE Essential 2580 TOWRANG Essential 2580 WAYO Essential 2580 WIARBOROUGH Essential 2580 WINDELLAMA Essential 2580 WOLLOGORANG Essential 2580 WOMBEYAN CAVES Essential 2580 WOODHOUSELEE Essential 2580 YALBRAITH Essential 2580 YARRA Essential 2581 BELLMOUNT FOREST Essential 2581 BEVENDALE Essential 2581 BIALA Essential 2581 BLAKNEY CREEK Essential 2581 BREADALBANE Essential 2581 BROADWAY Essential 2581 COLLECTOR Essential 2581 CULLERIN Essential 2581 DALTON Essential 2581 GUNNING Essential 2581 GURRUNDAH Essential 2581 LADE VALE Essential 2581 LAKE GEORGE Essential 2581 LERIDA Essential 2581 MERRILL Essential 2581 OOLONG Essential ©2021 ACN Inc. -

Seasonal Buyer's Guide

Seasonal Buyer’s Guide. Appendix New South Wales Suburb table - May 2017 Westpac, National suburb level appendix Copyright Notice Copyright © 2017CoreLogic Ownership of copyright We own the copyright in: (a) this Report; and (b) the material in this Report Copyright licence We grant to you a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, revocable licence to: (a) download this Report from the website on a computer or mobile device via a web browser; (b) copy and store this Report for your own use; and (c) print pages from this Report for your own use. We do not grant you any other rights in relation to this Report or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast, or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without our prior written permission. Permissions You may request permission to use the copyright materials in this Report by writing to the Company Secretary, Level 21, 2 Market Street, Sydney, NSW 2000. Enforcement of copyright We take the protection of our copyright very seriously. If we discover that you have used our copyright materials in contravention of the licence above, we may bring legal proceedings against you, seeking monetary damages and/or an injunction to stop you using those materials. You could also be ordered to pay legal costs. If you become aware of any use of our copyright materials that contravenes or may contravene the licence above, please report this in writing to the Company Secretary, Level 21, 2 Market Street, Sydney NSW 2000. -

Collector Wind Farm Environmental Assessment

APP Corporation Collector Wind Farm Environmental Assessment June 2012 STATEMENT OF VALIDITY Submission of Environmental Assessment Prepared under Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 by: Name: APP Corporation Pty Ltd Address: Level 7, 116 Miller Street North Sydney NSW 2060 In respect of: Collector Wind Farm Project Applicant and Land Details Applicant name RATCH Australia Corporation Limited Applicant address Level 13, 111 Pacific Highway North Sydney NSW 2060 Land to be developed Land 6,215ha in area within the Upper Lachlan Shire, located along the Cullerin Range, bound to the north by the Hume Highway and to the south by Collector Road, comprising the lots listed in Table 1 of the Environmental Assessment. Proposed development Construction and operation of up to 68 wind turbines with installed capacity of up to 228MW, and associated electrical and civil infrastructure for the purpose of generating electricity from wind energy. Environmental Assessment An Environmental Assessment (EA) is attached. Certification I certify that I have prepared the contents of this EA and to the best of my knowledge: • it contains all available information that is relevant to the environmental assessment of the development to which the EA relates; • it is true in all material particulars and does not, by its presentation or omission of information, materially mislead; and • it has been prepared in accordance with the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 Signature Name NICK VALENTINE Qualifications BSc (Hons), MAppSc Date 30 June 2012 Collector Wind Farm Environmental Assessment June 2012 APP Corporation Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ I 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 2 1.1. -

Gunning Shire Council

GUNNING SHIRE COUNCIL SECTION 94 (ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND ASSESSMENT ACT 1979) CONTRIBUTIONS PLAN for the Provision of Public Amenities and Services PREPARED JANUARY 1995 SECTION 4.3 – REVISED 2000 AND AUGUST 2006 GUNNING SHIRE COUNCIL SECTION 94 CONTRIBUTIONS PLAN CHRONOLOGY DATE NAME OF PLAN DETAILS OF PLAN OR AMENDMENT January 1995 Gunning Shire Council Section 94 Comprehensive Contributions Plan contributions plan. 18 September Gunning Shire Council Section 94 Section 4.3 – Road and 2000 Contributions Plan Traffic Facilities revised. 8 September Yass Valley Council Section 94 Plan repeals Gunning 2004 Contributions Plan 2004 Shire Council Section 94 Contributions Plan except Section 4.3 – Road and Traffic Facilities which remains in force. 9 August Amendment to Gunning Shire Amendment to the 2006 Council Section 94 Contributions contribution per base unit Plan demand of roads on less than Category 1 standard. 4.3 ROADS & TRAFFIC FACILITIES REVISED ROADWORKS Contributions Plan ADOPTED BY GUNNING SHIRE COUNCIL DATE 18 SEPTEMBER 2000 RES NO 351 4.3.1 INTRODUCTION This Revised Roadworks Contributions Plan revises and replaces Section 4.3 of Gunning Shire Council’s Contributions Plan for the Provision of Public Services and Facilities JANUARY 1995. 4.3.1.1 AIM OF THE REVISED PLAN This Revised s94 Roadworks Contribution Plan provides the framework for the determination of equitable and fair contributions by (a) setting out a pattern for distribution of traffic flows within the Shire. SEE ANNEXURES 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 & 1.4 (b) putting in place a strategy for Council to add or remove roads, and to vary the classification of roads to which this plan applies, to accommodate changing local circumstances. -

State Electoral Roll

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources · books on fully searchable CD-ROM 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide A complete range of Genealogy software · · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries · gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter Specialist Directories, War records, Regional FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK histories etc. www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources · free information and content, newsletters and blogs, speaker www.familyphotobook.com.au biographies, topic details www.findmypast.com.au · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, organisations and commercial partners · Free software download to create 35 million local and family records for throughout Australia and New Zealand · professional looking personal photo books, Australian, New Zealand, Pacific Islands, and calendars and more Papua New Guinea New South Wales Electoral Roll 1913 volume 7 Ref. AU2200-1913-07 ISBN: 978 1 74222 701 6 This book was kindly loaned to Archive Digital Books Australasia by the Society of Australian Genealogists http://www.sag.org.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

STFC Delivery Postcodes & Suburbs

STFC Delivery Postcodes ID Name Suburb Postcode 1 SYD METRO ABBOTSBURY 2176 1 SYD METRO ABBOTSFORD 2046 1 SYD METRO ACACIA GARDENS 2763 1 SYD METRO ALEXANDRIA 2015 1 SYD METRO ALEXANDRIA 2020 1 SYD METRO ALFORDS POINT 2234 1 SYD METRO ALLAMBIE HEIGHTS 2100 1 SYD METRO ALLAWAH 2218 1 SYD METRO ANNANDALE 2038 1 SYD METRO ARNCLIFFE 2205 1 SYD METRO ARNDELL PARK 2148 1 SYD METRO ARTARMON 2064 1 SYD METRO ASHBURY 2193 1 SYD METRO ASHCROFT 2168 1 SYD METRO ASHFIELD 2131 1 SYD METRO AUBURN 2144 1 SYD METRO AVALON BEACH 2107 1 SYD METRO BALGOWLAH 2093 1 SYD METRO BALGOWLAH HEIGHTS 2093 1 SYD METRO BALMAIN 2041 1 SYD METRO BALMAIN EAST 2041 1 SYD METRO BANGOR 2234 1 SYD METRO BANKSIA 2216 1 SYD METRO BANKSMEADOW 2019 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN 2200 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN AERODROME 2200 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN NORTH 2200 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN SQUARE 2200 1 SYD METRO BARANGAROO 2000 1 SYD METRO BARDEN RIDGE 2234 1 SYD METRO BARDWELL PARK 2207 1 SYD METRO BARDWELL VALLEY 2207 1 1 SYD METRO BASS HILL 2197 1 SYD METRO BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 1 SYD METRO BAYVIEW 2104 1 SYD METRO BEACON HILL 2100 1 SYD METRO BEACONSFIELD 2015 1 SYD METRO BEAUMONT HILLS 2155 1 SYD METRO BEECROFT 2119 1 SYD METRO BELFIELD 2191 1 SYD METRO BELLA VISTA 2153 1 SYD METRO BELLEVUE HILL 2023 1 SYD METRO BELMORE 2192 1 SYD METRO BELROSE 2085 1 SYD METRO BELROSE WEST 2085 1 SYD METRO BERALA 2141 1 SYD METRO BEVERLEY PARK 2217 1 SYD METRO BEVERLY HILLS 2209 1 SYD METRO BEXLEY 2207 1 SYD METRO BEXLEY NORTH 2207 1 SYD METRO BEXLEY SOUTH 2207 1 SYD METRO BIDWILL 2770 1 SYD METRO BILGOLA BEACH -

Descendants of James Booth

Descendants of James Booth by Monica Jones and Rhonda Brownlow [email protected] Generation No. 1 JAMES 1 BOOTH was born 1797 in Dublin Ireland, and died 05 Dec 1855 in Gundaroo NSW. He married MARGARET ROBINSON 26 Dec 1832 in St. Peter's Church of England, Campbelltown, NSW. She was born 1808 in Paisley Renfrewshire, Scotland, and died 12 Jul 1884 in Gundaroo NSW. James BOOTH, b 1797 Dublin, Ireland and Margaret ROBINSON, b 1808 Scotland married in Campbelltown in 1832, he had applied for permission to marry, at that time he was free, but Margaret was still on a bond, they proceeded to have a large family of 10 children. The family was to reside at ‘Willowgrove Estate’ Gundaroo, where he had made an initial purchase in 1837 of 150 acres from Archibald MacLeod, this was to become the Willowgrove Estate a squattage of some 1000 acres. James Booth was transported in 1822 (age 25) on the Countess of Harcourt , while a Margaret ROBINSON was transported in 1827 on the Princess Charlotte. The ages given for both would have been correct. Additionally, this James Booth was transported from Wicklow in Ireland, having received 7 year sentence, while Charlotte was transported from Glasgow in Scotland after being tried 1826 Assizes, sentence 7 years she was sent straight to the Female Factory at Parramatta in1828. He was assigned to Dr. Douglas at Gerringong on the 1828 Census; he received his ticket of leave 1828/477. Countess of Harcourt 1822 The Countess of Harcourt was built in India in 1811. -

Gang-Gang November 2007.Pub

Gang-gang November 2007 Newsletter of the Canberra Ornithologists Group Inc. Monthly Meeting What to watch out for this month 8 pm November By the end of October most of the spring/summer migrants had arrived, with 14 November 2007 the only regularly visiting migrant species I’ve haven’t seen or heard reported being the Rufous Fantail and the Cicadabird. The continuing drought has Canberra Girls Grammar School also lead to an influx of White-browed and Masked Woodswallows, though corner Gawler Cres and Melbourne unlike last year most seem to be moving through or over quickly, rather than Ave, Deakin. The meetings are held in to attempt to stay and breed. Perhaps this reflects that with the ever deeply the Multi-media Theatre at the School. biting drought breeding conditions in the ACT region this year are not suit- Enter off Gawler Crescent using the able for them. Certainly from observations in my local area, and from feed- school road signposted as Gabriel back from the blitz etc, species numbers seem to be well down this spring. Drive. If that car-park is full, enter The grim conditions are reflected by the observation of species usually found using Chapel Drive. much further to the west, firstly the Black-eared Cuckoo , and then a number Dick Schodde will give a presentation on of Red-backed Kingfishers , over the the Melithreptus honeyeaters , which lo- past month. The Painted Snipe seen at cally include the common White-naped , Kelly’s Swamp may also reflect the the often overlooked Brown-headed , and extremely dry conditions inland, as do the Black-chinned Honeyeaters found to the west of the ACT. -

August 2009 Issue Page 2Southern Tablelands Heritage Automotive the Wheel Restorers Club

Southern Tablelands Heritage Automotive Restorers Club Inc. Page 1 The Pyett Family’s 1960 Sunbeam Rapier August 2009 Issue Page 2Southern Tablelands Heritage Automotive The Wheel Restorers Club PO Box 1420, Queanbeyan NSW 2620 President Ian McLeish 02 6230 3344 Vice President Bob Cannon 02 6299 1901 Secretary Jane Nock 02 6230 3320 Public Officer George Cook 02 4847 5081 Treasurer Gary Hatch 02 6297 4647 Events Director Allan Boyd 02 6297 6014 Events Committee Christine Hillbrick-Boyd 02 6297 6014 Max de Oliver 02 6297 7763 Lawrie Nock 02 6230 3320 John Corbett 02 6297 7285 Registrar John Corbett 02 6297 7285 Vehicle Inspector Albert Neuss 02 6297 6225 Council Delegates Allan Boyd, Laurie Nock Editor Ron Scattergood 02 6236 3219 Publishing Rhonda & John Winnett, Krystyna McLeish, Committee Geoff Rudd, Jane Nock Property Officers John & Ronda Cornwell 02 6297 3174 Webmaster Richard Marson 02 6230 3463 Club Website: www.stharc.org.au Club Email: [email protected] Editor’s Email: [email protected] Club Meetings are held at 8pm on the first Tuesday of each month (except January) at the Girl Guide Hall, Erin Street, Queanbeyan. Contributions should be submitted by the 15th of the month for the following month's issue. Articles covering events, members’ experiences, automotive/mechanical items or photographs welcomed. Photos will be returned. The editor reserves the right to accept, reject or modify any section of any article that has been submitted for publication. The opinions and views expressed in the articles published in The Wheel are wholly those of the respective authors, and not necessarily those of the Editor, or the Committee of the Southern Tablelands Heritage Automotive Restorers Club Inc. -

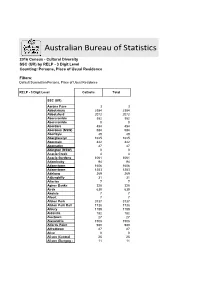

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census - Cultural Diversity SSC (UR) by RELP - 3 Digit Level Counting: Persons, Place of Usual Residence Filters: Default Summation Persons, Place of Usual Residence RELP - 3 Digit Level Catholic Total SSC (UR) Aarons Pass 3 3 Abbotsbury 2384 2384 Abbotsford 2072 2072 Abercrombie 382 382 Abercrombie 0 0 Aberdare 454 454 Aberdeen (NSW) 584 584 Aberfoyle 49 49 Aberglasslyn 1625 1625 Abermain 442 442 Abernethy 47 47 Abington (NSW) 0 0 Acacia Creek 4 4 Acacia Gardens 1061 1061 Adaminaby 94 94 Adamstown 1606 1606 Adamstown 1253 1253 Adelong 269 269 Adjungbilly 31 31 Afterlee 7 7 Agnes Banks 328 328 Airds 630 630 Akolele 7 7 Albert 7 7 Albion Park 3737 3737 Albion Park Rail 1738 1738 Albury 1189 1189 Aldavilla 182 182 Alectown 27 27 Alexandria 1508 1508 Alfords Point 990 990 Alfredtown 27 27 Alice 0 0 Alison (Central 25 25 Alison (Dungog - 11 11 Allambie Heights 1970 1970 Allandale (NSW) 20 20 Allawah 971 971 Alleena 3 3 Allgomera 20 20 Allworth 35 35 Allynbrook 5 5 Alma Park 5 5 Alpine 30 30 Alstonvale 116 116 Alstonville 1177 1177 Alumy Creek 24 24 Amaroo (NSW) 15 15 Ambarvale 2105 2105 Amosfield 7 7 Anabranch North 0 0 Anabranch South 7 7 Anambah 4 4 Ando 17 17 Anembo 18 18 Angledale 30 30 Angledool 20 20 Anglers Reach 17 17 Angourie 42 42 Anna Bay 789 789 Annandale (NSW) 1976 1976 Annangrove 541 541 Appin (NSW) 841 841 Apple Tree Flat 11 11 Appleby 16 16 Appletree Flat 0 0 Apsley (NSW) 14 14 Arable 0 0 Arakoon 87 87 Araluen (NSW) 38 38 Aratula (NSW) 0 0 Arcadia (NSW) 403 403 Arcadia Vale 271 271 Ardglen -

Graeme Barrow This Book Was Published by ANU Press Between 1965–1991

Graeme Barrow This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. Canberra region car tours Graeme Barrow PL£A*£ RETURN TO Australian National University Press Canberra, Australia, London, England and Miami, Fla., USA, 1981 First published in Australia 1981 Australian National University Press, Canberra © Text and photographs, Graeme Barrow 1981 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Barrow, Graeme: Canberra region car tours. ISBN 0 7081 1087 8. 1. Historic buildings — Australian Capital Territory — Guide-books. I. Title. 919.47’0463 Library of Congress No. 80-65767 United Kingdom, Europe, Middle East, and Africa: Books Australia, 3 Henrietta St., London WC2E 8LU, England North America: Books Australia, Miami, Fla., USA Southeast Asia: Angus & Robertson (S.E. Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: United Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Design by ANU Graphic Design Adrian Young Typeset by Australian National University Printed by The Dominion Press, Victoria, Australia To Nora -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE – 16 February 2018

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE – 16 February 2018 Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 18 Friday, 16 February 2018 The New South Wales Government Gazette is the permanent public record of official NSW Government notices. It also contains local council, private and other notices. From 1 January 2018, each notice in the Government Gazette has a unique identifier that appears in square brackets at the end of the notice and that can be used as a reference for that notice (for example, [n2018-14]). The Gazette is compiled by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and published on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) under the authority of the NSW Government. The website contains a permanent archive of past Gazettes. To submit a notice for gazettal – see Gazette Information. By Authority ISSN 2201-7534 Government Printer 606 NSW Government Gazette No 18 of 16 February 2018 Government Notices GOVERNMENT NOTICES Rural Fire Service Notices TOTAL FIRE BAN ORDER Prohibition on the Lighting, Maintenance and Use of Fires in the Open Air Being of the opinion that it is necessary or expedient in the interests of public safety to do so, I direct by this order that the following parts of the State for the periods specified the lighting, maintenance or use of any fire in the open air is prohibited (subject to the exemptions specifically listed hereunder and further set out in the Schedule of standard exemptions to total fire bans published in the NSW Government Gazette No 16 of 9 February 2018): Fire Weather Area Classes of Exemption Greater Hunter 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Central Ranges Northern Slopes North Western This direction shall apply for the periods specified hereunder: 00:01 hours to 23:59 hours on Sunday 11 February 2018.