Cornwall Beach & Dune Management Plans – Harvey's Towans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

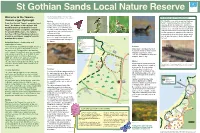

St Gothian Sands Local Nature Reserve

St Gothian Sands Local Nature Reserve As the seasons change, look out for the Welcome to the Towans - following wildlife in this part of the towans: St Gothian Sands’ Industrial past Towans a’gas Dynnergh Spring The Red River enters the sea at the Gwithian From the Cornish ‘Tewyn’, meaning ‘sand From early March, flocks of sand beach. It gets its name from mineral waste dune’, the towans between Hayle and martins, with swallows and house associated with tin mining in the Camborne/ Gwithian make up Cornwall’s second martins can be seen skimming over Redruth area. In the late 19th century, deposits of tin ore were extracted from the beach sand largest sand dune ecosystem, extending the water in the main lagoon. These Cinnabar moth migrants have just returned from over- and processed on site. Horses and carts were for around 400 hectares. The famous Photo Credit: David Chapman wintering in Africa. used to transport the sand as well as buckets beaches of St Ives Bay lying below you Stonechat Skylark suspended on wires attached to pylons which provide a continuous supply of sand to Wheatears have also come back - were bedded in concrete blocks and can still these are easily viewed on the open maintain these dunes. St Gothian Sands Key be seen. dune grasslands around the edge of Path NORTH the lagoon. Track St Gothian Sands – Ownership and Minor road National Trust Fencing P car park Moorhen explanation of name Power lines Electricity station Concrete blocks (tin streaming) (tin streaming) Formerly known as Gwithian Sandpit, this area Sand areas Autumn was a focus for gravel and sand extraction Sand areas with stone Many waders and waterfowl visit Marram grass for many years- for agriculture and building – Chimney St Gothian Sands on their autumn Scale until Cornwall Council took over the ownership 100m migration south for the winter. -

Wave Hub Appendix N to the Environmental Statement

South West of England Regional Development Agency Wave Hub Appendix N to the Environmental Statement June 2006 Report No: 2006R001 South West Wave Hub Hayle, Cornwall Archaeological assessment Historic Environment Service (Projects) Cornwall County Council A Report for Halcrow South West Wave Hub, Hayle, Cornwall Archaeological assessment Kevin Camidge Dip Arch, MIFA Charles Johns BA, MIFA Philip Rees, FGS, C.Geol Bryn Perry Tapper, BA April 2006 Report No: 2006R001 Historic Environment Service, Environment and Heritage, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] www.cornwall.gov.uk 3 Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by Halcrow and carried out by the projects team of the Historic Environment Service (formerly Cornwall Archaeological Unit), Environment and Heritage, Cornwall County Council in partnership with marine consultants Kevin Camidge and Phillip Rees. Help with the historical research was provided by the Cornish Studies Library, Redruth, Jonathan Holmes and Jeremy Rice of Penlee House Museum, Penzance; Angela Broome of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Truro and Guy Hannaford of the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, Taunton. The drawing of the medieval carved slate from Crane Godrevy (Fig 43) is reproduced courtesy of Charles Thomas. Within the Historic Environment Service, the Project Manager was Charles Johns, who also undertook the terrestrial assessment and walkover survey. Bryn Perry Tapper undertook the GIS mapping, computer generated models and illustrations. Marine consultants for the project were Kevin Camidge, who interpreted and reported on the marine geophysical survey results and Phillip Rees who provided valuable advice. -

South West Bees Project Andrena Hattorfiana 2016

Cornwall – June/July/August 2016 September 2016 Will Hawkes – Volunteer Saving the small things that run the planet Contents 1. Summary--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 2. Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 3. Species description-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 4. Field surveys---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 5. Survey Sites ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------7-16 5.1 Overview of Sites---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------7 Map 1 Bee and Scabious records of Cornwall---------------------------------------------------7 5.2 Gwithian Towans-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------8-10 5.2.1 Overview----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------8-9 5.2.2 Areas to improve--------------------------------------------------------------------------------9 5.2.3 Scabious locations and bee sightings table----------------------------------------------10 Map 2 Bee and Scabious records of Gwithian Towans--------------------------------------10 5.3 Kelsey Head and West Pentire----------------------------------------------------------------------11-15 -

Application for Designation As a Bathing Water Annex E Mexico Towan, Hayle, Cornwall

Application for designation as a bathing water Annex E Mexico Towan, Hayle, Cornwall March 2017 1 © Crown copyright 2017 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.3. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/ or email [email protected] This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Bathing Water team Defra Area 3D Nobel House 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 8026 3462 www.gov.uk/defra 2 Location and facilities This Annex summarises the evidence for the designation of Mexico Towan as a bathing water. Mexico Towan is situated on a long stretch of dunes in St Ives Bay known as The Towans, where two of the beaches are already designated as bathing waters: The Towans (Hayle) and The Towans (Godrevy). The facilities available at the Mexico Towan area are indicated on the map: Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) lifeguards from May - September Public toilets Shops or kiosks Nearby parking Beach usage in 2015 The figures provided by Cornwall Council were compiled by the RNLI and cover the 2015 bathing season because the figures for 2016 had not been finalised when the application was submitted. Defra’s requirements for evidence of the number of bathers are explained in the main consultation document, which is available on Citizenspace. The RNLI’s methodology for the counts of beach users is also explained in the consultation document. -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

Report on the English Bathing Waters in Need Of

Surfers Against Sewage Are Calling For A Review of the UK’s Bathing Water Sample Sites. Surfers Against Sewage (SAS) believe the weekly bathing water samples required by the EU Bathing Water Directive should be taken from the area of the bathing water that presents bathers and water users with the greatest source of pollution, if a significant amount of bathers and recreational water users can be expected to regularly use that are area of beach. Surfers Against Sewage are concerned that a number the UK’s designated bathing water sample spots around the UK do not provide a true guide to the water quality that a bather or water user might experience at our bathing waters. The implications are incredible concerning, as our widely promoted water quality results could be misleading the public about the potential health risk at a number of the UK’s bathing water. The Bathing Water Directive states (Art3.3) the monitoring point should be where most bathers are expected or the greatest risk of pollution is expected, according to the bathing water profile. In the UK Regulations (Schedule 4.1) Defra have transposed the obligation to locate the monitoring point where the most bathers are expected. This was part of the original transposition The European Commission’s Reference Document for the monitoring and assessment requirements of the revised Bathing Water Directive published August 2014 states: • A bathing water is not defined by its physical size. The length of its corresponding beach can vary between bathing waters and the distribution of bathers within a bathing water can be uneven. -

Hayle Historical Assessment by Cornwall Archaeological Unit

Hayle Historical Assessment Cornwall Main Report Cornwall Archaeological Unit A Report for English Heritage Hayle Historical Assessment Cornwall Nick Cahill BA, IHBC (Conservation Consultant) with Cornwall Archaeological Unit July 2000 CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNIT A service of the Environment Section of the Planning Directorate, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements The Hayle Historical Assessment was commissioned by English Heritage (South West Region), with David Stuart (Historic Areas Advisor) providing administrative assistance and advice. The CRO, RIC and Cornwall Local Studies Library provided assistance with the historical research. Comments on the draft report were provided by English Heritage, Georgina Schofield (Hayle Community Archive), Brian Sullivan (Hayle Old Cornwall Society), Stella Thomas (Hayle Town Trust) and Rob Lello (Hayle Town Councillor). Within Cornwall Archaeological Unit, Jeanette Ratcliffe was the Project Manager, Bryn Perry Tapper collated historical data and created the Hayle GIS maps and SMR database, and Andrew Young identified sites visible on air photographs (as part of English Heritage’s National Mapping Programme). Nick Cahill (freelance consultant working for CAU) carried out historical research and fieldwork and prepared the report text. The report maps were produced by Bryn Perry Tapper and the Technical Services Section of CCC Planning Directorate from roughs provided by Nick Cahill. Cover illustration Hayle harbour in 1895, viewed from the Towans, above the later power station. North Quay is in the foreground, East Quay in the centre, and South Quay, Carnsew Dock, the railway viaduct and Harvey’s Foundry are in the background. -

The Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2016 - 2021

The Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2016 - 2021 Safeguarding our landscape’s beauty and benefits for future generations PUBLIC CONSULTATION DRAFT: FEBRUARY 2016 Closing date for comments is Midday on Monday 21st March 2016 via online survey monkey https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/AONBPLAN or by downloading Word version of questionnaire via http://www.cornwallaonb.org.uk/management-plan Q1. Optional: Please give your contact details so we can contact you if necessary to discuss your response: Name Organisation Email/phone Forewords (to be inserted) Rory Stewart, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Joyce Duffin, Cornwall Council Cabinet Member for Environment and Housing Dr Robert Kirby-Harris, Cornwall AONB Partnership Chair 2 Contents Introduction The Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Managing the AONB Strategy for the Cornwall AONB – Place and People Vision Place People Aims Place People Delivery Plan – Key priorities for collaboration Geographical priorities Monitoring Policy Place Policies Cultivating Character Managing Development Investing in Nature Responding to Climate Change Nurturing Heritage Revitalising access 3 People Policies Vibrant Communities Health and Happiness Inspiring Culture Promoting Prosperity Local Sections 01 Hartland 02 Pentire Point to Widemouth 03 The Camel Estuary 04 Carnewas to Stepper Point (formerly Trevose Head to Stepper Point) 05 St Agnes 06 Godrevy to Portreath 07 West Penwith 08 South Coast Western 09 South Coast Central 10 South Coast Eastern 11 Rame Head 12 Bodmin Moor Appendix 1 A summary of landscape change in the AONB since 2008 Appendix 2 The National Planning Policy Framework with respect to AONB Appendix 3 Major Developments in the AONB 4 Introduction What is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty? Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty are particularly special landscapes whose distinctive character and natural beauty are so outstanding that it is in the nation’s interest to safeguard them. -

Visit Wcornwall Guide Final

Issue one Issue one Days out in Days out in West Cornwall by boot, bus and branchline West Cornwall This document is printed on paper from managed renewable sources. by boot, bus and branchline in association with First in Devon & Cornwall The vegetable based inks used are the new environmentally friendly alternative to mineral based inks, they are produced from organic matter and are bio-degradable With thanks to these organisations: P-TAG Penwith Tourism Action Group If you require this ‘Days out in West Cornwall’ guide in a different format, for example large print, please contact us on 01736 336844 or St Ives Hotel and [email protected] Guesthouse Association Please be aware that providing these formats will incur a short delay. Designed and produced in West Cornwall by www.graemeandrust.co.uk 01872 552286 St Ives Hayle Penzance Lands End St Just introduction Surround yourself with the rich contents variety of experiences on offer, 2 map 4 beautiful britain explore our unique environment. 9 7 ways Think Global - Stay Local. 10 explore 12 south coast 16 the prom 18 far west Everything you need for a 22 north coast breathtaking day out is right here in 26 gardens 28 beaches West Cornwall, whether you are a 30 ancient sites 32 resources resident or on holiday. 34 on your doorstep 36 the AONB 38 food 44 festivals 46 art and culture 48 made in Cornwall enjoy 50 town plans 52 days out 56 attractions 64 accommodation outstanding natural beauty unspoilt beaches ancient ruins stunning landscapes enchanting walks world heritage family -

Cornwall Coast Path Free

FREE CORNWALL COAST PATH PDF Henry Stedman,Joel Newton,Daniel McCrohan | 352 pages | 20 Jul 2016 | Trailblazer Publications | 9781905864713 | English | Hindhead, Surrey, United Kingdom The Most Beautiful Coastal Walks in Cornwall Culture Trip stands with Black Lives Matter. Select currency. My Plans. Open menu Menu. St Agnes to Perranporth Hiking Trail. Add to Plan. A short walk of 3. The ascent takes you out of Cornwall Coast Path valley, when Trevaunance Cove bursts into view. With just one steep up-and-down, amble along turquoise coves accessible only to kayaks and surfers. Your final view as you enter Perranporth will be line after line of waves breaking on the beach. Get some well-deserved rest at this gorgeous stone cottagea short stroll from the beach at St Agnes, with its welcoming restaurants and pubs. Built on the ocean-facing land of the West Polberro mine, the one-bedroom cottage can sleep three, and makes the perfect romantic escape. More Info. Open In Google Maps. Visit website. Clinging to the edge of southeast Cornwall and just a seven-minute boat trip from Plymouth, Mount Edgcumbe boasts gardens that are a heady-scented wonderland of flowers. With stunning views of Plymouth Sound and the South Devon coast, follow Cornwall Coast Path pathway until you reach a stretch of grassland known as Minadew Brakes. After a breather, zigzag through woodland and across beaches until you reach the twin villages of Kingsand and Cawsand. The Cross Keys Inn in Cawsand has an excellent range of local ales, with outside seating and live music on Sundays. -

CORNWALL 218 Atmospheric of All, During the Roaring Surf Andbitter Windsofcornwall’Sferalatmospheric Ofall,Duringtheroaringsurf Winter

© Lonely Planet Publications 218 lonelyplanet.com THE NORTH COAST 219 Orientation & Information detail on ways to get to and from the county Cornwall stretches from the River Tamar and p295 for countywide travel. C o r n w a l l and the granite hump of Dartmoor in the Cornwall 24 (www.cornwall24.co.uk) Lively (and usually east all the way to mainland England’s most heated) Cornwall discussion forum. westerly point at Land’s End. The principal Cornwall Beach Guide (www.cornwallbeachguide administrative town, Truro, sits bang in the .co.uk) Online guide to the county’s finest sand. middle of the county; to the north are the Cornwall Online (www.cornwall-online.co.uk) A lofty cliffs and surfing beaches of the north community-based site with guides to accommodation, And gorse turns tawny orange, seen beside coast, while the south coast is a gentler walks, attractions, villages and activities. Pale drifts of primroses cascading wide landscape of fields, river estuaries and quiet To where the slate falls sheer into the tide. beaches. The main A30 road cuts through the middle of the county, running roughly THE NORTH COAST Sir John Betjeman, Cornish Cliffs parallel with the main-line railway between London Paddington and Penzance; a second If it’s the classic Cornish combination of Jutting out into the churning sea and cut off from south Devon by the broad River Tamar, major road (the A38) runs east from Ply- lofty cliffs, sweeping bays and white-horse Cornwall (or Kernow, as its usually known around these shores) has always seen itself as a mouth across the Tamar Bridge and along surf you’re after, then make a beeline for the nation apart from the rest of England – another country, not just another English county.