Assessment of Conflict Dynamics in Mercy Corps' Area of Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Peace Is Not Peaceful : Violence Against Women in the Central African Republic

The programme ‘Empowering Women for Sustainable Development’ of the European Union in the Central African Republic When Peace is not Peaceful : Violence against Women in the Central African Republic Results of a Baseline Study on Perceptions and Rates of Incidence of Violence against Women This project is financed by the The project is implemented by Mercy European Union Corps in partnership with the Central African Women’s Organisation When Peace is not Peaceful: Violence Against Women in the Central African Republic Report of results from a baseline study on perceptions of women’s rights and incidence of violence against women — Executive Summary — Mercy Corps Central African Republic is currently implementing a two-year project funded by the European Commission, in partnership with the Organization of Central African Women, to empower women to become active participants in the country’s development. The program has the following objectives: to build the capacities of local women’s associations to contribute to their own development and to become active members of civil society; and to raise awareness amongst both men and women of laws protecting women’s rights and to change attitudes regarding violence against women. The project is being conducted in the four zones of Bangui, Bouar, Bambari and Bangassou. For many women in the Central African Republic, violence is a reality of daily life. In recent years, much attention has been focused on the humanitarian crisis in the north, where a February 2007 study conducted by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs highlighted the horrific problem of violence against women in conflict-affected areas, finding that 15% of women had been victims of sexual violence. -

Iom Regional Response

IOM REGIONAL RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT │ 9 - 22 June 2015 IOM providing health care assistance to returnees in Gaoui. (Photo: IOM Chad) SITUATION OVERVIEW Central African Republic (CAR): Throughout the country, the general situation has remained calm over the course of the reporting period. On 22 June, the National Elections Authority (ANE) of CAR announced the electoral calendar marking the timeline for return of the country to its pre-conflict constitutional order. As per the ANE calendar, the Constitutional Referendum is CAR: IOM handed over six rehabilitated classrooms at the scheduled to take place on 4 October, and the first round of Lycee Moderne de Bouar in western CAR. Parliamentary and Presidential Elections on 18 October 2015. However, concern remains over the feasibility of the plan due to the limited time left for voter registration, especially considering the large number of IDP and refugees. CHAD: IOM completed the construction of 300 emergency Currently, there are 399,268 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in shelters that will accommodate 413 returnees hosted in CAR, including 33,067 people in Bangui and Bimbo (Source: Kobiteye and Danamadja temporary sites. Commission for Population Movement). CAMEROON: On 18 June, IOM’s team in Garoua Boulai distributed WFP food parcels to 56 households (368 CAMP COORDINATION AND CAMP MANAGEMENT Under the CCCM/NFI/Shelter Cluster and in coordination with individuals). UNHCR, WFP, the Red Cross, World Vision, and PU-AMI, IOM continues the voluntary return of IDPs from the Mpoko displacement site. As of 22 June, 2,872 IDP households have been deregistered from the Mpoko displacement site, of which 2,373 participated in the “My Peace Hat” workshop at Nasradine School, have been registered in their district of return. -

Niger Stages Historic Elections Despite Jihadist Bloody Attacks Poll Could Seal a First Peaceful Handover Between Elected Presidents

Established 1961 7 International Monday, December 28, 2020 Niger stages historic elections despite jihadist bloody attacks Poll could seal a first peaceful handover between elected presidents NIAMEY: Voters went to the polls in Niger yester- mer interior and foreign minister. “It is a great pride day for an election that could seal a first peaceful that this date of December 27 has been respected,” handover between elected presidents, against the Bazoum said after voting. Bazoum’s main rival, former backdrop of a bloody jihadist insurgency. The West prime minister Hama Amadou, was barred from con- African country, unstable since gaining independ- testing the vote on the grounds that in 2017 he was ence from France 60 years ago, is ranked the world’s handed a 12-month jail term for baby trafficking-a poorest country according to the UN’s Human charge he says was bogus. Development Index. Around 7.4 million people are registered to vote for the ballot for presidency, which Overshadowed by insecurity coincides with legislative elections. Polling stations are scheduled to close at 7:00 pm “I expect the Nigerien but are instructed to close president to put security, later in case of delays to health, progress and ensure 11 hours of voting. democracy first,” Campaigning Partial results for the presi- Aboubakar Saleh, a 37- dential election are expect- year-old launderer, told overshadowed ed to be announced today AFP in Niamey without with final counts on revealing who he voted by insecurity Wednesday or Thursday. A for. Issaka Soumana, a 52- second round, if necessary, year-old lorry driver, said will be held on February 20. -

Hdpt-Car-Info-Bulletin-Eng-164.Pdf

Bulletin 164 01/03/10 – 15/03/11 | Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team | CAR www.hdptcar.net Newsletter 2011 fairs in Bouar and Bozoum Bouar Fair: Under the theme "the Future of Farmers, 01 – 15 March 2011 the Future of the Central African", the second edition of the agricultural fair organized by Mercy Corps and Caritas took place in Bouar, Nana-Mambere Highlights Prefecture (West) from 19 to 20 February. Some 104 agricultural groups and women’s associations - Inaugural swearing-in ceremony of President participated in this fair and obtained a profit of almost François Bozizé 19 million FCFA. Sales from a similar fair in 2010 - Refugees, Asylum Seekers and IDPs in CAR amounted to 15 million FCFA. Groups and associations managed by Mercy Corps also provided - Internews activities in CAR information on their activities. During this fair, a Food Bank set up by Caritas in partnership with the Background and security Association Zyango Be-Africa, was inaugurated. Various groups exhibited and sold products such as Inaugural swearing-in ceremony of the President millet, maize, sesame seeds, peanuts, coffee and On 15 March Francois Bozizé was sworn-in as rice. A separate section was also reserved for cattle, President of the Central African Republic for a second goat, chicken and guinea fowl breeders. Prizes were mandate of 5 years, by the Constitutional Court. awarded to 28 groups based on three main criteria: Francois Bozizé pledged to respect the Constitution exhibition, economic value and variety of products of CAR and to ensure the well being of Central exhibited. Prizes included two cassava mills donated Africans. -

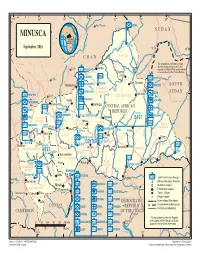

MINUSCA Aoukal S U D a N

14 ° 16 ° 18 ° 20 ° 22 ° 24 ° 26 ° Am Timan ZAMBIA é MINUSCA Aoukal S U D A N t CENTRAL a lou AFRICAN m B u a REPUBLIC a O l h r a r Birao S h e September 2016 a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° ° a a B b C h VAKAGAVAVAKAKAGA a r C H A D i The boundaries and names shown Garba and the designations used on this Sarh HQ Sector Center map do not imply official endorsement ouk ahr A Ouanda or acceptance by the United Nations. B Djallé PAKISTAN UNPOL Doba HQ Sector East Sam Ouandja BANGLADESH Ndélé K S O U T H Maïkouma o MOROCCO t BAMINGUIBAMBAMINAMINAMINGUINGUIGUI t o BANGLADESH BANGORANBABANGBANGORNGORNGORANORAN S U D A N BENIN 8° Sector West Kaouadja 8° HQ Goré HAUTE-KOTTOHAHAUTHAUTE-HAUTE-KOUTE-KOE-KOTTKOTTO i u a g PAKISTAN n Kabo i CAMBODIA n i n i V BANGLADESH i u b b g i Markounda i Bamingui n r UNPOL r UNPOL i CENTRAL AFRICAN G G RWANDA Batangafo m NIGER a REPUBLIC Paoua B Sector CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro SRI LANKA PERU OUHAMOUOUHAHAM Yangalia EAST m NANANA -P-PEN-PENDÉENDÉ a Mbrès OUAKOUOUAKAAKA UNPOL h u GRGRÉBGRÉBIZGRÉBIZIÉBIZI UNPOL HAUT-HAHAUTUT- FPU CAMEROON 1 Bossangoa O ka MBOMOUMBMBOMOMOU a MAURITANIA o Bouca u Dékoa Bria Yalinga k Dékoa n O UNPOL i Bozoum OUHAMOUOUHAHAM h Ippy C Sector UNPOL i Djéma 6 BURUNDI r 6 ° a ° Bambari b Bouar CENTER rra Baoro M Oua UNPOL Baboua Baoro Sector Sibut NANA-MAMBÉRÉNANANANANA-MNA-MNA-MAM-MAMBÉAMBÉAMBÉRÉBÉRÉ Grimari Bakouma MBOMOUMBMBOMOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KÉMKKÉMOÉMO m Bossembélé M b angúi bo er OMOMBEOMBELLOMBELLA-MPOKOBELLA-BELLYalokeYaloYaLLA-MPLLA-lokeA-MPOKA-MPMPOKOOKO ub UNPOL mo e O -

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEFCAR/2018/Matous February 2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 28 February 2019 1.5 million - On 6 February the Central African Republic (CAR) government and # of children in need of humanitarian assistance 14 of the country’s armed groups signed a new peace agreement in 2.9 million Khartoum (Sudan). The security and humanitarian situation still # of people in need remained volatile, with the Rapid Response Mechanism recording 11 (OCHA, December 2018) new conflict-related alerts; 640,969 # of Internally displaced persons - In February, UNICEF and partners ensured provision of quality (CMP, December 2018) primary education to 52,987 new crisis-affected children (47% girls) Outside CAR admitted into 95 temporary learning spaces across the country; - 576,926 - In a complex emergency context, from 28 January to 16 February, # of registered CAR refugees UNICEF carried out a needs assessment and provided first response (UNHCR, December 2018) in WASH and child protection on the Bangassou-Bakouma and Bangassou-Rafaï axes in the remote Southeast 2018 UNICEF Appeal US$ 59 million - In Kaga-Bandoro, three accidental fires broke out in three IDP sites, Funding status* ($US) leaving 4,620 people homeless and 31 injured. UNICEF responded to the WASH and Education needs UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funds received: Sector/Cluster UNICEF $2,503,596 Key Programme Indicators Cluster Cumulative UNICEF Cumulative Target results (#) Target results (#) Carry-Over: $11,958,985 WASH: Crisis-affected people with access to safe water for drinking, 800,000 188,705 400,000 85,855 cooking and personal hygiene Education: Children (boys and girls 3-17yrs) attending school in a class 600,000 42,360 442,500 42,360 Funding Gap: led by a teacher trained in 44,537,419 psychosocial support $ Health: People and children under 5 in IDP sites and enclaves with access N/A 82,068 7,806 to essential health services and medicines. -

Central-African-Republic-COVID-19

Central African Republic Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation Report n°7 Reporting Period: 1-15 July 2020 © UNICEFCAR/2020/A.JONNAERT HIGHLIGHTS As of 15 July, the Central African Republic (CAR) has registered 4,362 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within its borders - 87% of which are local Situation in Numbers transmissions. 53 deaths have been reported. 4,362 COVID-19 In this reporting period results achieved by UNICEF and partners include: confirmed cases* • Water supplied to 4,000 people in neighbourhoods experiencing acute 53 COVID-19 deaths* shortages in Bangui; *WHO/MoHP, 15 July 2020 • 225 handwashing facilities set up in Kaga Bandoro, Sibut, Bouar and Nana Bakassa for an estimate of 45,000 users per day; 1.37 million • 126 schools in Mambere Kadei, 87 in Nana-Mambere and 7 in Ouaka estimate number of prefectures equipped with handwashing stations to ensure safe back to children affected by school to final year students; school closures • 9,750 children following lessons on the radio; • 3,099 patients, including 2,045 children under 5 received free essential million care; US$ 29.5 funding required • 11,189 children aged 6-59 months admitted for treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) across the country; UNICEF CAR’s • 1,071 children and community members received psychosocial support. COVID-19 Appeal US$ 26 million Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs As of 15 July, the Central African Republic (CAR) has registered 4,362 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within its borders - which 87% of which are local transmissions. 53 deaths have been reported. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a decrease in number of new cases does not mean an improvement in the epidemiological situation. -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Iom Regional Response

IOM REGIONAL RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT │ 3 - 16 March 2015 IOM’s infrastructure cleaning activities underway, Bangui. (Photo: IOM CAR) SITUATION OVERVIEW Central African Republic (CAR): In Bangui, the situation continues to be calm albeit unpredictable. Many armed attempts of hold- ups of humanitarian actors’ vehicles and break-ins by anti-Balaka were reported in Bangui and its vicinity. Caution and vigilance CAR: IOM provided ongoing maintenance for five boreholes, have been recommended to UN and other humanitarian staffs 50 latrines and 47 emergency showers at the IDP sites locat- following criminal activities along the main roads between Bangui ed Kabo and Moyenne Sido. and several other towns. UN, NGO and private vehicles are becoming targets of regular attacks by criminal gangs with some of them posing as political or military groups. CHAD: Shelter construction continues in the Kobiteye trans- IOM, through its offices in Bangui, Kabo and Boda, has been it site near Goré with a total of 300 shelters built to date. providing assistance to IDPs, returnees and other conflict-affected populations. IOM also continues working on social cohesion through activities that include all communities, and actively participates in the UN task force in charge of preparing for the CAMEROON: IOM’s medical teams conducted consultations Parliamentary and Presidential elections which are expected to for 63 cases in Kenztou and 45 cases in Garoua Boulai. take place in CAR later in 2015. As of 3 March, there are currently 436,256 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in CAR, including 49,113 people hosted in sites in Bangui and its environs (Source: Commission for Population host families within Kabo and Moyenne Sido. -

Africa's Role in Nation-Building: an Examination of African-Led Peace

AFRICA’S ROLE IN NATION-BUILDING An Examination of African-Led Peace Operations James Dobbins, James Pumzile Machakaire, Andrew Radin, Stephanie Pezard, Jonathan S. Blake, Laura Bosco, Nathan Chandler, Wandile Langa, Charles Nyuykonge, Kitenge Fabrice Tunda C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2978 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0264-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Air Force photo/ Staff Sgt. Ryan Crane; Feisal Omar/REUTERS. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the turn of the century, the African Union (AU) and subregional organizations in Africa have taken on increasing responsibilities for peace operations throughout that continent. -

Security Council Distr.: General 13 April 2015

United Nations S/2015/248 Security Council Distr.: General 13 April 2015 Original: English Letter dated 10 April 2015 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith a note verbale from the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations dated 31 March 2015 and a report on the activities of Operation Sangaris in the Central African Republic, for transmittal to the Security Council in accordance with its resolution 2149 (2014) (see annex). (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 15-05794 (E) 130415 130415 *1505794* S/2015/248 Annex [Original: French] The Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations presents its compliments to the Office of the Secretary-General, United Nations Secretariat, and has the honour to inform it of the following: pursuant to paragraph 47 of Security Council resolution 2149 (2014), the Permanent Mission of France transmits herewith the report on the actions undertaken by French forces from 15 November 2014 to 15 March 2015 in support of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) (see enclosure). The Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations would be grateful if the United Nations Secretariat would bring this report to the attention of the members of the Security Council. 2/5 15-05794 S/2015/248 Enclosure Operation Sangaris Support to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic in the discharge of its mandate Period under review: -

December 2016

December 2016 Summary This submission focuses on abductions, killing, and maiming of children; the protection of education; sexual violence; and the rights of children with disabilities. It relates to Articles 2, 6, 19, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 34, 35, 37, 38, and 39 of the Convention, and proposes issues and questions that Committee members may wish to raise with the government. Human Rights Watch has conducted extensive field research and documented grave child rights violations since 2013.1 Background On December 10, 2012, the Seleka, an alliance of predominantly Muslim rebel groups from the marginalized northeast of the Central African Republic, began a military campaign against the government.2 The Seleka moved southwest into non-Muslim areas, killing thousands of civilians. On March 24, 2013, Seleka rebels took control of Bangui, the capital, and ousted President François Bozizé. Michel Djotodia, one of the Seleka leaders, suspended the constitution, and installed himself as interim president—a role to which he was subsequently appointed by the transitional government.3 In August 2013, animist and Christian militia known as “anti-balaka,” in an attempt to seize power and retaliate against the Seleka, began to target Muslim residents and committed serious human rights violations.4 President Djotodia dissolved the Seleka in September 2013. The Seleka were pushed out of Bangui and the southwest in early 2014 by African Union and French forces and established strongholds in the center and east. However, by October 2014, the Seleka had fractured into smaller groups, each controlling territory. The Central African Republic has experienced ongoing fighting since 2013.