Volume 25, Number 07, December 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 4-24-1972 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1972). Winona Daily News. 1152. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/1152 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fair to partly cloudy and warmer Tuesday 117th Year of Publican*© n Fire out of lunar orbit tonight North Viet Astronauts set for return . SPACE CENTER, Houston C AP) — Apollo L6's explorers linkup two hours later with Mattingly in Casper. fire out of lunar orbit tonight to start the Jong journey borne "What a ride! What a ride!" Duke shouted as Orion with a treasure strip of rocks that scientists believe will prove blasted away from the mountainous Descartes plateau at tJlllM C . t VA01I& the moon long ago was wracked by volcanoes. 7:36 p.m . CST ending a 71-hour surface expedition during CllBlW/ . .lIVUp9 'Ihe major finds came Sunday, on the third moon drive which the moonmen set records for the amount of rocks that almost was canceled because Mission Control felt the collected, time on the surface and speed traveled by their astronauts might be tired and pressed for time as a result classy moon buggy. of their late landing Thursday "night. The two ships maneuvered around one another as Mat- tingly took pictures of the effects of the liftoff on Orion's They return -with 245 pounds of materials which repre- gingerly moved together nose-to-nose. -

Volume 3 Issue 8 2010 Your Access to Performance with Passion

volume 3 issue 8 2010 Your Access to Performance with Passion. *Sentient Charter is a program of Sentient Jet, LLC (“Sentient”). Sentient arranges flights on behalf of clients with FAR Part 135 air carriers that exercise full operational control of charter flights at all times. Flights will be operated by flights at all times. Flights will be operated by full operational control of charter that exercise air carriers 135 Part flights on behalf of clients with FAR LLC (“Sentient”). Sentient arranges *Sentient Charter is a program of Sentient Jet, details.) for to www.sentient.com/standards standards safety and additional establishedSentient. (Refer by service been certified to provide Sentient and that meet all FAA for that have air carriers 135 Part FAR At Sentient*, we understand that success isn’t something that comes easily. It takes focus, years of preparation and relentless dedication. With an innovative 9-point safety program and a staff of service professionals available 24/7, it’s no wonder that Sentient is the #1 arranger of charter flights in the country. Sentient Charter can take you anywhere on the world’s stage - on the jet you want - at the competitive price you deserve. Sentient Jet is the Proud Platinum Sponsor of the TourLink 2010 Conference Jet Barbeque TO LEARN MORE, PLEASE CONTACT: David Young, Vice President - Entertainment, at [email protected] or 805.899.4747 More than 560 attorneys and advisors in offices across the southeastern U.S. and Washington, D.C., practicing a broad spectrum of business law including transactions, contracts, litigation, transportation and entertainment. -

My Guitar Is a Camera

My Guitar Is a Camera John and Robin Dickson Series in Texas Music Sponsored by the Center for Texas Music History Texas State University–San Marcos Gary Hartman, General Editor Casey_pages.indd 1 7/10/17 10:23 AM Contents Foreword ix Steve Miller Acknowledgments xi Introduction xiii Tom Reynolds From Hendrix to Now: Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey xv Herman Bennett, with Watt M. Casey Jr. 1. Witnesses: The Music, the Wizard, and Me 1 Mark Seal 2. At Home and on the Road: 1970–1975 11 3. Got Them Texas Blues: Early Days at Antone’s 31 4. Rolling Thunder: Dylan, Guitar Gods, and Joni 54 5. Willie, Sir Douglas, and the Austin Music Creation Myth 60 Joe Nick Patoski 6. Cosmic Cowboys and Heavenly Hippies: The Armadillo and Elsewhere 68 7. The Boss in Texas and the USA 96 8. And What Has Happened Since 104 Photographer and Contributors 123 Index 125 Casey_pages.indd 7 7/10/17 10:23 AM Casey_pages.indd 10 7/10/17 10:23 AM Jimi Hendrix poster. Courtesy Paul Gongaware and Concerts West. Casey_pages.indd 14 7/10/17 10:24 AM From Hendrix to Now Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey HERMAN BENNETT, WITH WATT M. CASEY JR. Watt Casey’s journey as a photographer can be In the summer of 1970, Watt arrived in Aus- traced back to an event on May 10, 1970, at San tin with the intention of getting a degree from Antonio’s Hemisphere Arena: the Cry of Love the University of Texas. Having heard about a Tour. -

CLAIR a MANUFACTURING, DESIGN, BROTHERS TEXAS T I ENGINEERING O N Dallas, TX

Integration excellence through co n c e p t , d e s i officesand affiliates g n a n d a p p l i CORPORATE OFFICES, c SHOWCO/CLAIR a MANUFACTURING, DESIGN, BROTHERS TEXAS t i ENGINEERING o n Dallas, TX . Lititz, PA 8204 Elmbrook, Suite 142 One Ellen Ave. Dallas, TX 75427 Lititz, PA 17543 Contact: Contact: CLAIR BROTHERS Contact: ML Procise, Rentals John Blasutta, Systems Troy Clair, Touring P: (214) 638-3326 Integration Gene Pelland, Systems F: (214) 638-3245 P: (972) 839-8838 Integration [email protected] F: (972) 808-9124 P: (717) 626-4000 www.showco.com [email protected] sys ems F: (717) 625-3816 t [email protected] www.clair-audio.com CLAIR BROTHERS CLAIR BROTHERS LA / AUDIO RENT/CLAIR NASHVILLE SOUNDWORX BROTHERS EUROPE Nashville, TN Los Angeles, CA Basel, Switzerland 3327 Ambrose Ave. 13926 Equitable Rd. Industriestrasse 111, Nashville, TN 37207 Cerritos, CA 90703 CH-4147 Aesch Contact: Contact: J.D. Brill Contact: Dan Heins, Sales P: (562) 229-1550 Juerg Hugin Ralph Mastrangelo, Rentals F: (562) 229-1530 P: 41-61-756-98-00 P: (615) 227-6657 [email protected] F: 41-61-756-98-01 F: (615) 227-7989 [email protected] [email protected] www.md-clair.com CLAIR BROTHERS JAPAN DISTRIBUTORS Tokyo, Japan WINKY PRODUCTIONS HANSAM TRS 355 Orimoto-Cho Tsuzuki-Ku Unit 9 6/F Tower 1 Harbour 185-4, Hansam B/D Yokohama City Centre.1 Hok Cheung St. BangEe-Dong, SongPa-Gu Shingawa-Ku Hunghom, Hong Kong Seoul, Korea Kanagawa 224 Japan Contact: Contact: Wayne Grosser Jae J. -

Volume 4 Issue 5 2011 Global Service & Live Shows Since 1966

volume 4 issue 5 2011 Global Service & Live Shows Since 1966 We offer a complete array of state-of-the-art sound reinforcement products, technical staff and services to the live production industry. We are only as good as our last show, and excellence is the only option. That’s the Clair way. www.clairglobal.com Bobcon Seger tenvolume 4 issuet 5 2011s 6 10 16 26 Beck A. (c) Michael mobilePRODUCTIONmonthly The Grand Ole Opry House HARMAN Soundcraft Vi6™ 16 4 Sound Post-Diluvium and Post-Bellum, Impresses at the Donaufestival An Improved Opry House Rises Out of the Flood L-ACOUSTICS K1 Sings With Andrea Bocelli 5 17 Schermerhorn Symphony Hall Restoration of a New Building 6 Crowd Barriers Mojo Barriers Innovation On The Agenda 22 Bob Seger Just Like it’s Always Been The Browning Group 10 Tour Management Tour Vendors Tour Management and Beyond 24 26 M.L. Procise & Clair 12 Nashville Under Water RECAP 26 Crew Members Michael Caporale Soundcheck Nashville 28 12 Finishes What He Starts No Matter How Long It Takes Moo TV / Ed Beaver Guitars / Rich Eckhardt 15 ReTune Nashville 32 Advertiser's Index mobile production monthly 1 FROM THE Publisher The cover feature this month features one of the longest running touring artists in our industry, Bob Seger. Appropriately, it also features one of the longest running production relationships, M.L. Procise, of Clair and Seger. Their work together has spanned over 30 years. In HOME OFFICE STAFF this era of shifting loyalties and questionable commitments, a 7 3 2 it is refreshing to see that there are still professionals who ph: 615.256.7006 • f: 615.256.7004 understand how to service and maintain a client. -

AES 123Rd Convention Program October 5 – 8, 2007 Jacob Javits Convention Center, New York, NY

AES 123rd Convention Program October 5 – 8, 2007 Jacob Javits Convention Center, New York, NY Special Event Program: LIVE SOUND SYMPOSIUM: SURROUND LIVE V Delivering the Experience 8:15 am – Registration and Continental Breakfast Thursday, October 4, 9:00 am – 4:00 pm 9:00 am – Event Introduction – Frederick Ampel Broad Street Ballroom 9:10 am – Andrew Goldberg – K&H System Overview 41 Broad Street, New York, NY 10004 9:20 am –The Why and How of Surround – Kurt Graffy Arup Preconvention Special Event; additional fee applies 9:50 am – Coffee Break 10:00 am – Neural Audio Overview Chair: Frederick J. Ampel, Technology Visions, 10:10 am – TiMax Overview and Demonstration Overland Park, KS, USA 10:20 am – Fred Aldous – Fox Sports 10:55 am – Jim Hilson – Dolby Labs Panelists: Kurt Graffy 11:40 am – Mike Pappas – KUVO Radio Fred Aldous 12:25 pm – Lunch Randy Conrod Jim Hilson 1:00 pm – Tom Sahara – Turner Networks Michael Nunan 1:40 pm – Sports Video Group Panel – Ken Michael Pappas Kirschenbaumer Tom Sahara 2:45 pm – Afternoon Break beyerdynamic, Neural Audio, and others 3:00 pm – beyerdynamic – Headzone Overview Once again the extremely popular Surround Live event 3:10 pm – Mike Nunan – CTV Specialty Television, returns to AES’s 123rd Convention in New York City. Canada 4:00 pm – Q&A; Closing Remarks Created and Produced by Frederick Ampel of Technology Visions with major support from the Sports PLEASE NOTE: PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE Video Group, this marks the event’s fifth consecutive PRIOR TO THE EVENT. FINAL PROGRAM WILL workshop exclusively provided to the AES. -

The Business the Musk Business: the Texas OBSERVER ° the Texas Observer Publishing Co

Senate and AG endorsements, p. 11 ER, R April 14 1978 500 -,- 1.4ktur-;;;"'"; ",•T--- ,2414 NtaGN ag*** The business The musk business: The Texas OBSERVER ° The Texas Observer Publishing Co.. 1978 who pays Ronnie Dugger, Publisher Vol. 70, No. 7 April 14, 1978 Incorporating the State Observer and the East Texas Demo- the piper? crat, which in turn incorporated the Austin Forum-Advocate. EDITOR Jim Hightower MANAGING EDITOR Lawrence Walsh ASSOCIATE EDITOR Linda Rocawich EDITOR AT LARGE Ronnie Dugger PRODUCTION MANAGERS: Susan Reid, Susan Lee By Mike Tolleson ASSISTANT EDITORS: Colin Hunter, Teresa Acosta, Austin Vicki Vaughan, Eric Hartman Has everybody got Saturday night fever? It would seem so, if STAFF ASSISTANTS: Margaret Watson, Bob Sindermann, Debbie Wormser, Margot Beutler, Leah Miller, Connie Larson, David the phenomenal growth of the record and music industry is any Guarino, Beth Epstein, Beverly Palmer, Harris Worcester, Gerald guide. McLeod, Larry Zinn, Janie Leigh Frank But as music lovers buy more records, tune in to more hours CONTRIBUTORS: Kaye Northcott, Jo Clifton, Dave McNeely, Don of radio, and drop in more frequently at concert halls and Gardner, Warren Burnett, Rod Davis, Paul Sweeney, Marshall Breger, honky-tonks, few realize that their pastime has become very big Jack Hopper, Stanley Walker, Joe Frantz, Ray Reece, Laura Eisenhour, Dan Hubig, Ben Sargent, Berke Breathed, Eje Wray, business, a bonanza firmly under the control of a handful of Luther Sperberg, Roy Hamric, Thomas D. Bleich, Mark Stinson, Ave record companies, radio chains, talent agents, and other Bonar, Jeff Danziger, Lois Rankin, Maury Maverick Jr., Bruce Cory, middlemen. -

Backstage Auctions, Inc. the Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog

Backstage Auctions, Inc. The Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog Lot # Lot Title Opening $ Artist 1 Artist 2 Type of Collectible 1001 Aerosmith 1989 'Pump' Album Sleeve Proof Signed to Manager Tim Collins $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1002 Aerosmith MTV Video Music Awards Band Signed Framed Color Photo $175.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1003 Aerosmith Brad Whitford Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1004 Aerosmith Joey Kramer Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1005 Aerosmith 1993 'Living' MTV Video Music Award Moonman Award Presented to Tim Collins $4,500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1006 Aerosmith 1993 'Get A Grip' CRIA Diamond Award Issued to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1007 Aerosmith 1990 'Janie's Got A Gun' Framed Grammy Award Confirmation Presented to Collins Management $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1008 Aerosmith 1993 'Livin' On The Edge' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1009 Aerosmith 1994 'Crazy' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1010 Aerosmith -

Recording-1981-12.Pdf

nc hicrIng - °RC SOUND yotsi r $2.50 DECEMBER 1981 Z.<7 VC LUME 12 - NUMBER 6 ENGINEER PRODUCIR 104c, a:)43'pril"t 4S\\\ ru .4 rr First look: STUDER's Digital Multitrack aid Universal Sampling Convene' - Digital Up iate, page 105 60 MIMM11111111111111M1=11111.1111M 1111111111M11111MIIIIIII 50 IMMI11111111111111=111r new ININI111111111111111111411111IMIM1UMAIIIIIIIIIIIIMIll 111111111111111111111M11111111111RAMIVAIIIMIMMIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII /1111111/41111011111111111 40 NIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIMIAIIIP.11111411/.111111111111111111111111111111 e 1111111111111111111WAIIIIIINIIIMIUMIR1IUPIELIINIIMI111111111 1.1110111MIIMAINCIIIIM. ;1 30 11111111111MMBMIVallPAM'MPAIIMMIIIIINEMMII1111111111B1111111111/1111111111AIIIIMMIAlt.1111, :11 20 t M111111111111%111111/40 aleuwmAiumourdinnullissui z 411111111.1d111111M11111111111111 INNINOEIMIVAMIPINP.111rillrAINIMPP:4111111011MMPIIIIII MUM ,Inmilwall'APAITAMIIIIIKalINIIIIMMIMAIZMI 10 MNIPWIIK/111,741P MP 41111111111LIN /11111111Gal01111"noille"=well 0 or immunimmooulimd.seslemsonstionli 01 02 0.5 1 2 5 10 2C 50 100 200 500 1000 STATI L3AD 144,44s -nch Figure 2: Static deflection of lams is 1-iad- thick fiberglass pad on application of load in pounds per square inch, for ty-Tas of itabody Moist Control Company isolators. SHOWCO doing the 'Stones Tour, page 62 Floating Floors, page 80 RELATING RECORDING ART TO RECORDING SCIENCE TO RECORDING EQUIPMENT www.americanradiohistory.com EXI=DANEI YOUFI M01:11ZONS To reach the stars in this business you need two things, talent and exceptionally good equipment. The AMEK 2500 is State of the Art design and technology respected worldwide. In the past 12 months alone, we've placed consoles in Los Angeles, Dallas, NewYork, Nashville, London, Frank- furt, Munich, Paris, Milan, Tokyo, Sydney, Guatemala City, and johannesberg. When you have a great piece of equipment, word gets around. The "2500" has become an industry standard. It's everything you want in a master recording console, and .. -

Texas-Internationa-Pop-Festival-1969

1 THE TEXAS INTERNATIONAL POP FESTIVAL – 1969 I. CONTEXT In 1969, the city of Lewisville, Texas was a small farm town of about 9,000 residents1. Located about twelve miles north of Dallas, the town sat in the midst of plowed fields and grassland bordered by Lewisville Lake on one side and the Interstate 35 pathway to Oklahoma on another. Until then, the biggest entertainment adventure ever held there was a rodeo or a Lewisville Farmers high school football game. On Labor Day weekend of that year, in the last throes of summer, and in the last gasp of the sixties, a decade of change for the nation and the world, twenty-five bands and as many as a 150,000* hippies, bikers and music lovers would converge on the unsuspecting Texas town. The result was a piece of Texas history that has never been matched. *Newspapers reported mostly conservative and conflicting numbers of 20,000,2 40,0003, 65,0004 and even 200,0005 attendees, however the promoters, who lost $100,000 on the event, insist that there were 125,000 to 150,000 based on ticket sales. Many of those who attended the Texas International Pop Festival, in 1969, would have considered themselves hippies. While hippies were known for their nonviolence, they were not always treated accordingly, often harassed wherever they went. Such harassment was especially acute in the state of Texas, where hippies were constantly hassled by others. That a pop festival for hippies could be held in Texas was no less than astounding. That one could be held, not in Dallas or Austin, but in a tiny farm town like Lewisville, was unbelievable. -

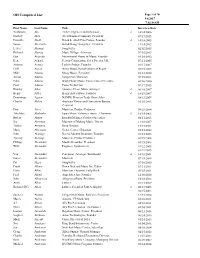

OH Completed List

OH Completed List Page 1 of 70 9/6/2017 7:02:48AM First Name Last Name Title Interview Date Yoshiharu Abe TEAC, Engineer and Innovator d 10/14/2006 Norbert Abel Abel Hammer Company, President 07/17/2015 David L. Abell David L. Abell Fine Pianos, Founder d 10/18/2005 Susan Aberbach Hill & Range Songs Inc., President 11/14/2012 Lester Abrams Songwriter 02/02/2015 Richard Abreau Music Village, Advocate 07/03/2013 Gus Acevedo International House of Music, Founder 01/20/2012 Ken Achard Peavey Corporation, Sales Director UK 07/11/2005 Antonio Acosta Luthier Strings, Founder 01/17/2007 Cliff Acred Amro Music, Band Instrument Repair 07/15/2013 Mike Adams Moog Music, President 01/13/2010 Arthur Adams Songwriter, Musician 09/25/2011 Edna Adams World Wide Music, Former Sales Executive 04/16/2010 Paul Adams Piano Technician 07/17/2015 Hawley Ades Shawnee Press, Music Arranger d 06/10/2007 Henry Adler Henry Adler Music, Founder d 10/19/2007 Dominique Agnew NAMM, Director Trade Show Sales 08/13/2009 Charles Ahlers Anaheim Visitor and Convention Bureau, 01/25/2013 President Don Airey Musician, Product Endorser 09/29/2014 Takehiko Akaboshi Japan Music Volunteer Assoc., Chairman d 10/14/2006 Bulent Akbay Istanbul Mehmet, Product Specialist 04/11/2013 Joy Akerman Museum of Making Music, Docent 11/30/2007 Toshio Akiyama Band Director 12/15/2011 Marty Albertson Guitar Center, Chairman 01/21/2012 John Aldridge Not So Modern Drummer, Founder 01/23/2005 Tommy Aldridge Musician, Product Endorser 01/19/2008 Philipp Alexander Musik Alexander, President 03/15/2008 Will Alexander Engineer, Synthesizers 01/22/2005 01/22/2015 Van Alexander Composer, Arranger, Bandleader d 10/18/2001 James Alexander Musician 07/15/2015 Pat Alger Songwriter 07/10/2015 Frank Alkyer Down Beat and Music Inc, Editor 03/31/2011 Davie Allan Musician, Guitarist, Early Rock 09/25/2011 Fred Allard Amp Sales, Inc, Founder 12/08/2010 John Allegrezza Allegrezza Piano, President 10/10/2012 Andy Allen Luthier 07/11/2017 Richard (RC) Allen Luthier, Friend of Paul A.