Safeguarding Commons for NEXT GENERATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatio - Temporal Analysis of Population Growth in the District Headquarters of Rajasthan

ISSN: 2319-8753 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (An ISO 3297: 2007 Certified Organization) Vol. 3, Issue 12, December 2014 Spatio - Temporal Analysis of Population Growth in the District Headquarters of Rajasthan Divya Shukla1, Rajesh Kr Dubey2 Assistant Professor, Home Nursing, St. John Ambulance Association, Ayodhya, U.P, India.1 Director, Prakriti Educational & Research Institute, Lucknow, UP, India.2 ABSTRACT: The rapid population growth results to economic difficulties, problems for resource mobilization, economic instability, increased unemployment, mounting external indebtness and finally low rate of progress. People were well aware about the importance of population studies from very ancient period. Explosively growing population has attracted the attention of social scientists and policy makers. For country like India, it is very important to study the decadal variation of population growth it helps in realizing problems. The population growth and socio economic changes are closely related to each other. In present study, Rajasthan has been chosen as study area. This state is the biggest state of our country having challenges of desert and desertification. In this state the distribution of population is irregular due to harsh physical condition. The aim of the present paper is to investigate the change in population growth rate in the District Head Quarters (DHQs) of Rajasthan during the three decades 1981-91, 1991-2001 and 2001-11. The present study is based on city/town level data obtained from the Directorate of Census Operations, Jaipur; Rajasthan. The data are concerned to the census 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011. Due to push- pull factors, the rural urban migration is causing the process of urbanization. -

Economics of Milk Production in Alwar District (Rajasthan): a Comparative Analysis

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 2, Issue 8, August 2012 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Economics of Milk Production in Alwar District (Rajasthan): A Comparative Analysis G. L. Meena* and D. K. Jain** * Department of Agricultural Economics and Management, MPUAT, Udaipur (Rajasthan) ** Division of Dairy Economics, Statistics and Management, NDRI, Karnal (Haryana) Abstract- This study covered 75 cooperative member milk 1. To compare the cost and return of milk production producers and 75 non-member milk producers which were post- among different herd size categories of households stratified into small, medium and large herd size categories. Per across member and non-member in different seasons. day net maintenance cost was found to be higher for member 2. To compare the production, consumption and marketed group than that of non-member group. It was found to be higher surplus of milk among different herd size categories of in case of buffalo than that of cow and also observed more in the households across member and non-member in different summer season. Per litre cost of buffalo and cow milk production seasons. was observed to be higher for the non-member as compared to member group. Per litre cost of buffalo milk production decreased with increase in herd size categories across different II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE seasons while same trend was not observed in case of cow milk Attempts have been made to review briefly the specific and production. Further, it was found higher in summer season. Daily relevant literature, which has direct or indirect bearing on the net return was found relatively higher in member group as objectives of the present study. -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

Sharma, V. & Sankhala, K. 1984. Vanishing Cats of Rajasthan. J in Jackson, P

Sharma, V. & Sankhala, K. 1984. Vanishing Cats of Rajasthan. J In Jackson, P. (Ed). Proceedings from the Cat Specialist Group meeting in Kanha National Park. p. 116-135. Keywords: 4Asia/4IN/Acinonyx jubatus/caracal/Caracal caracal/cats/cheetah/desert cat/ distribution/felidae/felids/Felis chaus/Felis silvestris ornata/fishing cat/habitat/jungle cat/ lesser cats/observation/Prionailurus viverrinus/Rajasthan/reintroduction/status 22 117 VANISHING CATS OF RAJASTHAN Vishnu Sharma Conservator of Forests Wildlife, Rajasthan Kailash Sankhala Ex-Chief Wildlife Warden, Rajasthan Summary The present study of the ecological status of the lesser cats of Rajasthan is a rapid survey. It gives broad indications of the position of fishing cats, caracals, desert cats and jungle cats. Less than ten fishing cats have been reported from Bharatpur. This is the only locality where fishing cats have been seen. Caracals are known to occur locally in Sariska in Alwar, Ranthambore in Sawaimadhopur, Pali and Doongargarh in Bikaner district. Their number is estimated to be less than fifty. Desert cats are thinly distributed over entire desert range receiving less than 60 cm rainfall. Their number may not be more than 500. Jungle cats are still found all over the State except in extremely arid zone receiving less than 20 cms of rainfall. An intelligent estimate places their population around 2000. The study reveals that the Indian hunting cheetah did not exist in Rajasthan even during the last century when ecological conditions were more favourable than they are even today in Africa. The cats are important in the ecological chain specially in controlling the population of rodent pests. -

Roll Number of Eligible Candidates for the Post of Process Server(S). Examination Will Be Held on 23Rd February, 2014 at 02.00 P.M

Page 1 Roll Number of eligible Candidates for the post of Process Server(s). Examination will be held on 23rd February, 2014 at 02.00 P.M. to 03.30 P.M (MCQ) and thereafter written test will be conducted at 04.00 P.M. to 05.00 PM in the respective examination centre(s). List of examination centre(s) have already been uploaded on the website of HP High Court, separetely. Name of the Roll No. Fathers/Hus. Name & Correspondence Address Applicant 1 2 3 2001 Ravi Kumar S/O Prem Chand, V.P.O. Indpur Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 176401 S/O Bishan Dass, Vill Androoni Damtal P.O.Damtal Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2002 Parveen Kumar 176403 2003 Anish Thakur S/O Churu Ram, V.P.O. Baleer Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 2004 Ajay Kumar S/O Ishwar Dass, V.P.O. Damtal Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 S/O Yash Pal, Vill. Bain- Attarian P.O. Kandrori Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2005 Jatinder Kumar 176402 2006 Ankush Kumar S/O Dinesh Kumar, V.P.O. Bhapoo Tehsil Indora, Distt. Kangra-176401 2007 Ranjan S/O Buta Singh,Vill Bari P.O. Kandrori Tehsil Indora , Distt.Kangra-176402 2008 Sandeep Singh S/O Gandharv Singh, V.P.O. Rajakhasa Tehsil Indora, Distt. Kangra-176402 S/O Balwinder Singh, Vill Nadoun P.O. Chanour Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2009 Sunder Singh 176401 2010 Jasvinder S/O Jaswant Singh,Vill Toki P.O. Chhanni Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 S/O Sh. Jarnail Singh, R/O Village Amran, Po Tipri, Tehsil Jaswan, Distt. -

Rajasthan's Minerals

GOVERNMENT oF RAJASmAN . I ' .RAJASTHAN'S . MINERALS FEBRUARY 1970 GOVERNMEN1'-UF R.J.JASM~ DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND GEOLOGY RAJASTHAN'S MINERALS FEBRUARY 1970 RAJASTHAN'S MINERALS Amongst the natural resources minerals by far enjoy a very important position because they are wasting asset compared to the . agricultural and forest . resources where if any mistakes have been committed at any time they can be rectified and resources position improved through manual effort. In case of minerals man has only his ingenuity to depend on in the search and so that exploitation of rock material which will give him the desired metals and· other chemicals made from minerals. He cannot grow them or ever create them but has· only to fulfil his requirements through the arduous trek from rich conce: ntrations of minerals to leaner ones as they become fewer and exhausted.· His. technical ingenuity is constantly put to a challenge in bringing more' dispsered metals to economic production. He has always to . be ca.refui that the deposit is not spoiled in winning the. mineral by ariy chance. Any damage done to a deposit cannot easily be rectified. · · · The position of minerals in the State of Rajastha~ all tbe more becomes very important for its economy because the agricultural and forest ~:esources are meagre and only a small portion of the States area is under cultivation. Not more than 20 years ago the potentiality of minerals in the· State was not so well known and one co.uld hardly say whether minerals would be able to play any important part in the economic development of the State. -

Census Atlas, Part IX-B, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan

PRG. 173 B (N) (Ordy.) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XIV RAJASTHAN PART IX-B CENSUS ATLAS C. S. GUPTA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Op~rations, RajalJhan 1969 FOREWORD FEW PEOPLE REALIZE, much less appreciate, that apart from the Survey of India and the Geological Survey, the Census of India had' been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian subcontinent. Intimate collaboration between geographer and demographer began quite early in the modern era, almost two centuries before the first experiments in a permanent decennial Census were made in the 1850's. For example, the population estimates of Fort St. George, Madras, made in 1639 and 1648, and of Masulipatnam and Bombay by Dr. John Fryer, around 1672-73 were supported by cartographic documents of no mean order, Tbe first detailed modern maps, the results of Major James Rennell's stupendous Survey of 1767-74, were published in 1778-1780 and Henry Taylor Colebrooke, almost our first systematic demographer, was quick to make good use of them by making estimates of population in the East India Company's Possessions in the 1780's. Upjohn's map of Calcutta City, drawn in 1792.93, reprinted in the Census Report of Calcutta for 195 I, gives an idea of the standards of cartographic excellence reached at that period. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Francis Buchanan Hamilton improved upon Colebrooke's method in which he was undoubtedly helped by the improved maps prepared for the areas he surve ed. It is possible that the Great Revenue Survey, begun in the middle of the last century, offered the best guarantee of the success of decennial population censuses proposed shortly before the Mutiny of 1857. -

TH-- ECONOMIP RF}SCT8 Og TH I P'jn. 3AB CANAL COLON ' "God

07 TH-- ECONOMIPRF}SCT8 Og TH I P'JN.3AB CANAL COLON' "Ye can Know them from their dsel1tnRe, " . eý 4ýu'ý ýý, ýi sa.. ý . _, ,. ý "God has said, from water all thine are made. I son g(,vently ordain that this funkle in which mib- ei tense i'z obtained wire thirst be converted into a place of comfort** AYbarl .:3 KAPAR SINGH BAJWA, 5w>ý,. ý''.: aýý.: +a...... Rý.:..: - ýxý,:. ýrüýii'ýa: ý. yoaýa: s, +. _.: ý. - .; ý; , wir' -ý`°'°--; "v. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Variable print quality CONTAINS PULLOUTS (1) 1 PRR7A0 To readers interested in the material progroas of the Province, no introduction zooms necessary for no fascinating, a subject as the "Enonoiio oftoota of the Punjab Fanal development of the Canal Poloniee. " The origin, .roath and colonies in an interesting and surprising; miracle or the 20th century -a miracle which has given rise to an Important trading city litt© Iyaulpur, the capital of the Lower Chonab Colony. T' e development of the Lower Bari Toab Colo yº has an Importance of its own as it ie the youngest of all its sister colonies and as most or us have soon the change that has come over the now Par* One can see what it wns like loss than ten years ago an one passes in the Karachi Mail through the desert skirting the youngest Canal Colon; yq not. a vestige of cultivation on either aide: only sand hills and a barren plaint dreariness unroolaimod save by the vivid tiiraie of water and trees. How this blight and hideousness of land, wao redeemed by the miracle of the 20th century and what are tho consequences of this change form the scope or shy thesis. -

Historical Background of Ground Water Exploitation / Exploration

GROUNDWATER EXPLORATION AND AUGMENTATION EFFORTS IN RAJASTHAN - A REVIEW - M.S. RATHORE INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES 8–B, Jhalana Institutional Area Jaipur– 302 004 February, 2005 1 Table of Contents SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................. 4 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND......................................................................................................................... 4 CATEGORIZATION OF AREAS FOR GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT ...................................................................... 6 Safe areas with potential for development..................................................................................................... 6 Semi-critical areas for cautious groundwater development.......................................................................... 6 Critical areas................................................................................................................................................. 6 Over-exploited areas ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Stage of groundwater -

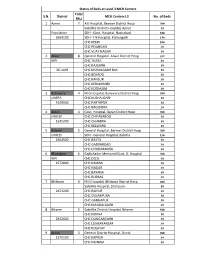

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 1 Ajmer 7 A K Hospital, Beawer District Hosp 300 Satellite District Hospital, Ajmer 30 Population SDH - Govt. Hospital, Nasirabad 100 2664100 SDH- Y N Hospital, Kishangarh 150 CHC KEKRI 100 CHC PISANGAN 30 CHC VIJAY NAGAR 30 2 Alwar 8 General Hospital, Alwar District Hosp 332 NIPI CHC TIJARA 30 CHC RAJGARH 50 36 LAKH CHC KISHANGARH BAS 50 CHC BEHROD 50 CHC BANSUR 30 CHC KERLIMANDI 30 CHC KOTKASIM 30 3 Banswara 4 M G Hospital, Banswara District Hosp 300 UNFPA CHC KUSHALGARH 50 1629900 CHC PARTAPUR 30 CHC BAGIDORA 30 4 Baran 4 Govt. Hospital, Baran District Hosp 300 UNICEF CHC CHIPABAROD 30 1245200 CHC CHHABRA 50 CHC KELWARA 30 5 Barmer 5 General Hospital, Barmer District Hosp 200 UNICEF SDH - General Hospital, Balotra 150 2404500 CHC BAYTU 30 CHC GADRAROAD 30 CHC DHORIMANNA 30 6 Bharatpur 6 RajBahadur Memorial Govt. D. Hospital 300 NIPI CHC DEEG 50 2572800 CHC KAMAN 30 CHC NAGAR 30 CHC BAYANA 50 CHC RUPBAS 30 7 Bhilwara 6 M G Hospital, Bhilwara District Hosp 400 Satellite Hospital, Shahpura 50 2453200 CHC RAIPUR 30 CHC GULABPURA 50 CHC GANGAPUR 50 CHC MANDALGARH 50 8 Bikaner 5 Satellite District Hospital, Bikaner 100 CHC NOKHA 50 2322600 CHC DUNGARGARH 30 CHC LUNKARANSAR 30 CHC KOLAYAT 30 9 Bundi 3 General District Hospital, Bundi 300 1170100 CHC KAPREN 30 CHC NAINWA 50 Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 10 Chittorgarh 5 District Hospital, Chittorgarh 300 1629900 CHC BEGUN 50 CHC KAPASAN 50 CHC BADISADRI 50 CHC NIMBAHERA 100 11 Churu 5 D B Hospital, Churu District Hospital 225 2059300 SDH - S R J Hospital, Ratangarh 100 SDH - S B Hospital, Sujangarh 100 CHC RAJGARH 50 CHC SARDARSHAHAR 75 12 Dausa 3 District Hospital, Dausa 150 NIPI CHC LALSOT 30 1606100 CHC MAHUWA 30 13 Dholpur 4 Sadar District Hospital, Dholpur 300 1196300 CHC RAJAKHERA 30 CHC BARI 50 CHC BASERI 30 14 Dungarpur 4 General District Hospital, Dungarpur 300 UNICEF SDH - Govt. -

Report of the South Asia Regional Session of the Global Biodiversity Forum 2003, Bangladesh

Report of the South Asia Regional Session of the Global Biodiversity Forum 2003, Bangladesh. 16-18 June 2003 Dhaka, Bangladesh IUCN - The World Conservation Union Bangladesh 2003, Forum Global Biodiversity Asia Regional Sessionofthe Report oftheSouth Founded in 1948, The World Conservation Union brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique world partnership: over 980 members in all, spread across some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. The World Conservation Union builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. Regional Biodiversity Programme, Asia (RBP) IUCN’s Regional Biodiversity Programme, Asia (RBP) was established 1996 to assist countries in Asia implement the Convention on Biological Diversity. Working with 12 countries in Asia, RBP is creating an enabling environment in the region through partnership with governments, NGOs, community based organisations, donors and other stakeholders on technical as well as policy issues. IUCN Regional Biodiversity Programme, Asia 53, Horton Place Colombo 7 Emilie Warner Balakrishna Pisupati Sri Lanka. Tel: ++94 11 4710439, ++94 11 2662941 (direct), ++94 11 2694094 (PABX) Fax: ++94 11 -

Final Population Figures, Series-18, Rajasthan

PAPER 1 OF 1982 CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 18 RAJASTHAN fINAL POPULATION FIGU~ES (TOTAL POPULATION, SCHEDULED CASTE POPULATION AND .sCHEDULED TRIBE POPULATION) I. C. SRIVASTAVA ·1)f the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Rajasthan INTRODUCfION The final figures of total population, scheduled caste and scheduled tribe population of Rajasthan Stat~ are now ready for release at State/District/Town and Tehsil levels. This Primary Census Abs tract, as it is called, as against the provisional figures contained in our three publications viz. Paper I, fFacts & Figures' and Supplement to Paper-I has been prepared through manual tabulation by over 1400 census officials including Tabulators, Checkers and Supervisors whose constant and sustained efforts spread over twelve months enabled the Directorate to complete the work as per the schedule prescribed at the national level. As it will take a few months more to publish the final population figures at the viJ1age as well as ward levels in towns in the form of District Census Handbooks, it is hoped, this paper will meet the most essential and immediate demands of various Government departments, autonomous bodies, Cor porations, Universities and rtsearch institutions in relation to salient popUlation statistics of the State. In respect of 11 cities with One lac or more population, it has also been possible to present ~the data by municipal wards as shown in Annexure. With compliments from Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (iii) Total Population, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribt' Population by Districts, 1981 Total Schedu1ed Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population. ( vi) 1. Ganganagar District 1 2.