Positive Action Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Base Architecture

filtering SIF Infrastructure Specification 3.3: Base Architecture www.A4L.org Version 3.3, May 2019 SIF Infrastructure Specification 3.3: Base Architecture Version 3.3, May 2019 1. Introduction .........................................................................................................................4 1.1. Preamble ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Guiding Principles ......................................................................................................... 4 1.3. Disclaimer ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4. Certification & Compliance Claims .............................................................................. 6 1.5. Permission and Copyright ............................................................................................ 6 1.6. Infrastructure Artifacts Overview ................................................................................ 7 1.7. Organization of Document ........................................................................................... 8 1.8. Document Conventions Definitions ............................................................................ 9 1.8.1. References ..................................................................................................................... 9 1.8.2. Terminology ................................................................................................................. -

Sample Pages to Thor

1 only A Stranger Arrives The air was dry and cold near the small town of Puente Antiguo, New Mexico. Darcy Lewis sat in the driver’s seatReview of an old van full of expensive scientic equipment. She was a college student working with scientist Jane Foster. Another scientist, ForDr. Erik Selvig, sat in the passenger seat. In the back of the van, Jane- opened the roof and climbed onto it. Selvig followed her, and they looked up into the darkness. “So what exactly are we looking for?” Selvig asked. He was a friend of Jane’s father and knew her well. “Why did you ask me to join you here in New Mexico?” “I told youSample. Something strange is happening in the night sky and I need your help,” Jane replied. “It’s a little dierent each time. Once it was a pool of stars in a corner of the sky. But last week it was a rainbow—” A noise from her computer stopped her. “Wait for it!” she said excitedly. Nothing happened. The sky above them stayed calm and black. Darcy put her head out of the window and looked up at Jane. “Can I turn on the radio?” she asked. She sounded bored. “No!” Jane replied angrily. She and Selvig climbed back inside the van. “I don’t understand,” she said. She opened a small book and looked at her notes. She always carried this notebook—inside it was her life’s work. M01_THOR_SB3_GLB_05991.indd 1 3/6/18 1:53 PM 2 “These changes have happened many times, always at night, Erik!” She checked her computer. -

A Traditional Story Many Myths, Legends, and Traditional Stories from Around the World Are About Such Things As Fire, Water, Rain, Wind, Or Thunder and Lightning

✩ A traditional story Many myths, legends, and traditional stories from around the world are about such things as fire, water, rain, wind, or thunder and lightning. Sometimes these things take the form of giants, gods, or spirits that can harm or help humans. Carefully read the following facts about Norse gods. Thor and Sif What Thor was like Thor was an exaggerated, colorful character. He was huge, even for a god, and incredibly strong. He had wild hair and beard and a temper to match. He was never angry for long, though, and easily forgave people. Thor raced across the sky in his chariot drawn by two giant goats, Toothgnasher and Toothgrinder. It was their hooves that people heard when it thundered on Earth. He controlled the thunder and lightning and brewed up storms by blowing through his beard. Sailors prayed to him for protection from bad weather. Thor’s magic weapons Thor had a belt which doubled his strength when he buckled it on and iron gauntlets which allowed him to grasp any weapon. The most famous of Thor’s weapons was his hammer, Mjollnir. It always hit its target and returned to Thor’s hands after use. When a thunderbolt struck Earth, people said that Thor had flung down his hammer. Mjollnir did not only do harm, though. It also had protective powers and people wore small copies of it as jewellery to keep them safe and bring good luck. Sif Thor was married to Sif, who was famous for her pure gold, flowing hair. She was a goddess of fruitfulness and plenty. -

M AA Teamups.Wps

Marvel : Avengers Alliance team-ups by Team-Up name _ Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. (50 points) = Black Widow / Hawkeye / Mockingbird Ambulancechasers (50 points) = Dare Devil / She Hulk Arachnophobia (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Widow / Spiderwoman Asgard (50 points) = Thor / Sif Assemble (50 points) = Thor / Hulk / Hawkeye / Black Widow / Ironman / Captain America Aviary (50 points) = all Heroes with a Flying ability Best Coast (50 points) = Hawkeye / Mockingbird / War Machine Birds of a Feather (50 points)= Hawkeye / Mockingbird Bloodlust (50 points) = Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif Cat Fight (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Black Cat Cosplayers (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Cat Defenders (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Hulk Egghead (50 points) = Hulk / Spiderman / Ironman / Mr.Fantastic Fantastic 4 (50 points) = all Fantastic 4 members Frenemies, Assemble (50 points) = Hawkeye / Black Widow Green Giants (50 points) = She-Hulk / Hulk Heroesforhire (50 points) = Luke Cage / Iron Fist Hard and Soft (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Colossus Hotstuff (50 points) = Phoenix / Human Torch Illuminati (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Mr.Fantastic / Ironman King&Queen (50 points) = Black Panther / Storm Marvelous (50 points) = Phoenix / Ms. Marvel Sibling Rivalry (50 points) = Invisible Woman / Human Torch Tinmen (50 points) = War Machine / Iron Man Tossers (50 points) = Thing / Hulk / She-Hulk / Phoenix X-Force (50 points) = all X-Men members X-lovers (50 points) = Cyclops / Phoenix by Hero name _ Black Cat + Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif = Bloodlust (50 points) Black Cat + Kitty Pryde = Cat Fight (50 points) Black Cat + Spiderman = Cosplayers (50 points) Black Panther + Storm = King&Queen (50 points) Black Widow + Hawkeye / Mockingbird = Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

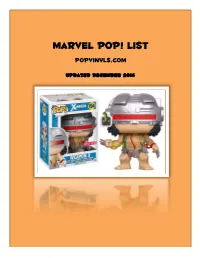

Marvel Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

Marvel Pop! List PopVinyls.com Updated December 2016 01 Thor 23 IM3 Iron Man 02 Loki 24 IM3 War Machine 03 Spider-man 25 IM3 Iron Patriot 03 B&W Spider-man (Fugitive) 25 Metallic IM3 Iron Patriot (HT) 03 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC ’11) 26 IM3 Deep Space Suit 03 Red/Black Spider-man (HT) 27 Phoenix (ECCC 13) 04 Iron Man 28 Logan 04 Blue Stealth Iron Man (R.I.CC 14) 29 Unmasked Deadpool (PX) 05 Wolverine 29 Unmasked XForce Deadpool (PX) 05 B&W Wolverine (Fugitive) 30 White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 Classic Brown Wolverine (Zapp) 30 GITD White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 XForce Wolverine (HT) 31 Red Hulk 06 Captain America 31 Metallic Red Hulk (SDCC 13) 06 B&W Captain America (Gemini) 32 Tony Stark (SDCC 13) 06 Metallic Captain America (SDCC ’11) 33 James Rhodes (SDCC 13) 06 Unmasked Captain America (Comikaze) 34 Peter Parker (Comikaze) 06 Metallic Unmasked Capt. America (PC) 35 Dark World Thor 07 Red Skull 35 B&W Dark World Thor (Gemini) 08 The Hulk 36 Dark World Loki 09 The Thing (Blue Eyes) 36 B&W Dark World Loki (Fugitive) 09 The Thing (Black Eyes) 36 Helmeted Loki 09 B&W Thing (Gemini) 36 B&W Helmeted Loki (HT) 09 Metallic The Thing (SDCC 11) 36 Frost Giant Loki (Fugitive/SDCC 14) 10 Captain America <Avengers> 36 GITD Frost Giant Loki (FT/SDCC 14) 11 Iron Man <Avengers> 37 Dark Elf 12 Thor <Avengers> 38 Helmeted Thor (HT) 13 The Hulk <Avengers> 39 Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 14 Nick Fury <Avengers> 39 Metallic Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 15 Amazing Spider-man 40 Unmasked Wolverine (Toytasktik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Gemini) 40 GITD Unmasked Wolverine (Toytastik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Japan Exc) 41 CA2 Captain America 15 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 B&W Captain America (BN) 16 Gold Helmet Loki (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 GITD Captain America (HT) 17 Dr. -

PDF Download Warriors 3 Pdf Free Download

WARRIORS 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George R R Martin,Gardner Dozois | 360 pages | 02 Aug 2011 | St Martin's Press | 9780765360281 | English | New York, United States Warriors 3 PDF Book The two player mode new to Dynasty Warriors 3 allows players to either go head-to-head in one-on-one fights or play co-operatively in any of the stages. Science Fiction. He gave high praise to how much the game was based on the original Romance of the Three Kingdoms story and even went as far as saying "All the costuming of the 3D models is ethnically authentic and beautifully lavished" whereas a number of reviews described the graphical quality as being plain and blurry Such as the said IGN review. Diana Gabaldon Goodreads Author Contributor. Archived from the original PDF on April 21, In co-operative play the characters retain their saved statistics, there are no alterations to the stage and the players gain the ability to perform a more powerful version of their Musou attack Special Attack. The Warriors Three were a team of elite Asgardian warriors, comprised of some of the best warriors of Asgard. Other books in the series. Namespaces Article Talk. Smartphone :. Something like that doesn't belong in an anthology like this one, in my opinion. IGN strongly criticized the Xbox version over the sound, both music and the voice acting. Nice diverse collection of stories! Start Your Free Trial. Zhu Rong and Nu Wa are exceptions as Zhu Rong was said to be the only female to have fought in that era and Nu Wa's character is fictional and based on ancient myth. -

Journey Into Mystery Featuring Sif: Seeds of Destruction (Marvel Now) Volume 2 Pdf

FREE JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY FEATURING SIF: SEEDS OF DESTRUCTION (MARVEL NOW) VOLUME 2 PDF Kathryn Immonen,Matteo Scalera,Valerio Schiti | 112 pages | 05 Nov 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9780785184478 | English | New York, United States Jeffrey Becker | Marvel The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Verified purchase: Yes Condition: Pre-owned. Skip to main content. About this product. Make an offer:. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Buy It Now. Add to cart. Make Offer. Horror in the hash house! The Warriors Three! And Journey into Mystery Featuring Sif: Seeds of Destruction (Marvel Now) Volume 2 Heimdall's dog! All these doughty heroes join forces to chain the vicious beast Journey into Mystery Featuring Sif: Seeds of Destruction (Marvel Now) Volume 2 and for all. Then: he's back, baby! See all 2 brand new listings. About this product Product Information Mayhem in the mess hall Horror in the hash house Volstagg's daughter, Hildegund, only wanted a midnight snack To the rescue come Sif Thor The Warriors Three And even Heimdall's dog All these doughty heroes join forces to chain the vicious beast once and for all. But unfortunately, everything they need to do it However, when a certain hammerwielding, space-faring ex shows up Additional Product Features Dewey Edition. -

THOR Written by Ashley Miller, Zack Stentz, & Don Payne

THOR Written by Ashley Miller, Zack Stentz, & Don Payne FADE IN: On the blackness of SPACE, beautiful and mysterious, strewn with a billion stars. Atop a building, a wrought-iron sign -- a HAMMER-WIELDING BLACKSMITH -- spins listlessly in the wind as a swirling breeze kicks up. A hint of what's to come. 1 EXT. PUENTE ANTIGUO, NEW MEXICO - NIGHT 1 1 A main street extends before us in this one-horse town, set amid endless flat, arid scrubland. A large SUV slowly moves down the street and heads out of town. 2 EXT. SUV - NIGHT 2 2 The SUV sits parked in the desert. Suddenly, the roof panels of the SUV FOLD OPEN. The underside of the panels house a variety of hand-built ASTRONOMICAL DEVICES, which now point at the sky. JANE FOSTER (late 20's) pops her head through the roof. She positions a MAGNETOMETER, so its monitor calibrates with the constellations above. It appears to be cobbled together from spare parts of other devices. JANE Hurry! We hear a loud BANG followed by muffled CURSING from below. Jane offers a hand down to ERIK SELVIG (60) who emerges as well, rubbing his head. JANE (CONT'D) Oh-- watch your head. SELVIG Thanks. So what's this "anomaly"¬ù of yours supposed to look like? JANE It's a little different each time. Once it looked like, I don't know, melted stars, pooling in a corner of the sky. But last week it was a rolling rainbow ribbon-- SELVIG (GENTLY TEASING) "Racing "Àúround Orion?"¬ù I've always said you should have been a poet. -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield. -

Will Thor Defeat the Hulk? Punching Friends?

8 months until ragnarok april 2017 WILL THOR DEFEAT THE HULK? PUNCHING FRIENDS? DESPITE THE FIRST IMPRESSION, THINGS LOOK GRIM. EITHER THE HULK DOESN’T REMEMBER, OR HE DOESN’T GIVE A DAMN! LOKI FINALLY GOT HIS DRINK! THE HORNY TRICKSTER GOT A SCOTCH, NO KIDDIN’ SPOILER ALERT: THE GRANDMASTER GAVE IT TO HIM, BEFORE LOKI TRICKED HIM. PAGE 3 PAGE 5 Loki’s helmet Shhh… Thor has couldn’t be a second hornier Hammer!! HELA: KISS MJOLNIR AND ASGARD GOODBYE! Seriously? 8 months until Ragnarok: You could pray to Loki asap, but he’ll probably trick you… The end is near! Thor: You could root for Thor, but do it super simple. The guy knows how Midgardians! Your time is running out! You can kiss to punch, but we all know he’s a Mjolnir, Asgard and Thor goodbye! Hela is about to rule little bit slow in understanding stuff. JUST-KEEP-IT-SIMPLE, and the show from November 3. She promised your deaths you might survive. would be quick. Then she’ll have fun with you once Odin: you’re in her domains. One-eye is lost somewhere in Midgard. The best option is asking Doctor Strange for some help. Hela is pissed. We still don’t know Heimdall: for certain, but it seems she has a If you’ve worshipped Loki, don’t tantrum of massive proportions. expect anything from him but a According to our faithful sources murdering look. He knows you (the comics and Norse Mythology) adore Loki, so… she might be one of Loki’s children. -

X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E. Shelton Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shelton, Lyndsey E., "X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 146. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/146 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in International Studies. By Lyndsey Erin Shelton Under the mentorship of Dr. Darin H. Van Tassell ABSTRACT It is a widely accepted notion that a child can only be called stupid for so long before they believe it, can only be treated in a particular way for so long before that is the only way that they know. Why is that notion never applied to how we treat, address, and present religion and the religious to children and young adults? In recent years, questions have been continuously brought up about how we portray violence, sexuality, gender, race, and many other issues in popular media directed towards young people, particularly video games. -

Thor, the Superhero

THOR, THE SUPERHERO Height: 6'6" Weight: 640 lbs Hair: Blond Eyes: Blue ORIGIN Thor is the son of Odin, the ruler of the extra-dimensional realm of Asgard, and the Elder Goddess Gaea, the personification of Mother Nature. Raised in Asgard, the goddess Frigga served as Thor's mother, and Thor grew up with Loki as his step-brother. His father Odin had Mjolnir, a mystical hammer enchanted by magic and made of Uru, forged for Thor but decreed it would be given to him only after he'd proven himself worthy of the right to possess and wield it by becoming a noble and honorable warrior of the highest order. Odin enchanted the, weapon so it could only be lifted by someone, including but not limited to Thor whom proved worthy by meeting these requirements. After years of training and accepting different quests to prove he was worthy of wielding the hammer, Thor still could not lift Mjolnir. However, he was only able to raise it after hearing about the kidnapping of Sif. Thor ignored the direct commands of his father and went into Odin's treasure room to retrieve the hammer. He found himself able to lift it with ease because he desired to save his friend instead of searching for personal glory. Thor spent several centuries adventuring, undertaking many quests, fighting battles, facing many foes and performing countless heroic deeds before eventually becoming Asgard's greatest warrior and protector. Thor's first love was the goddess Sif. Their relationship started when both were kids and it's had several ups and downs; sometimes seeming to end forever only to be renewed time after time.