• Articles • Becoming Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

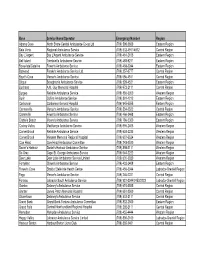

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 91 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2016 No. 43 GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD ACT NOTICE UNDER THE AUTHORITY of subsection 6(1), of the Geographical Names Board Act, RSNL1990 cG-3, the Minister of the Department of Municipal Affairs, hereby approves the names of places or geographical features as recommended by the NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD and as printed in Decision List 2016-01. DATED at St. John's this 19th day of October, 2016. EDDIE JOYCE, MHA Humber – Bay of Islands Minister of Municipal Affairs 337 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE October 28, 2016 Oct 28 338 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE October 28, 2016 MINERAL ACT DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES JUSTIN LAKE NOTICE Manager - Mineral Rights Published in accordance with section 62 of CNLR 1143/96 File #'s 774:3973; under the Mineral Act, RSNL1990 cM-12, as amended. 775:1355, 3325, 3534, 3614, 5056, 5110 Mineral rights to the following mineral licenses have Oct 28 reverted to the Crown: URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING ACT, 2000 Mineral License 011182M Held by Maritime Resources Corp. NOTICE OF REGISTRATION Situate near Indian Pond, Central NL TOWN OF CARBONEAR On map sheet 12H/08 DEVELOPMENT REGULATION AMENDMENT NO. 33, 2016 Mineral License 017948M Held by Kami General Partner Limited TAKE NOTICE that the TOWN OF CARBONEAR Situate near Miles Lake Development Regulations Amendment No. 33, 2016, On map sheet 23B/15 adopted on the 20th day of July, 2016, has been registered by the Minister of Municipal Affairs. -

(PL-557) for NPA 879 to Overlay NPA

Number: PL- 557 Date: 20 January 2021 From: Canadian Numbering Administrator (CNA) Subject: NPA 879 to Overlay NPA 709 (Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada) Related Previous Planning Letters: PL-503, PL-514, PL-521 _____________________________________________________________________ This Planning Letter supersedes all previous Planning Letters related to NPA Relief Planning for NPA 709 (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada). In Telecom Decision CRTC 2021-13, dated 18 January 2021, Indefinite deferral of relief for area code 709 in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) approved an NPA 709 Relief Planning Committee’s report which recommended the indefinite deferral of implementation of overlay area code 879 to provide relief to area code 709 until it re-enters the relief planning window. Accordingly, the relief date of 20 May 2022, which was identified in Planning Letter 521, has been postponed indefinitely. The relief method (Distributed Overlay) and new area code 879 will be implemented when relief is required. Background Information: In Telecom Decision CRTC 2017-35, dated 2 February 2017, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) directed that relief for Newfoundland and Labrador area code 709 be provided through a Distributed Overlay using new area code 879. The new area code 879 has been assigned by the North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) and will be implemented as a Distributed Overlay over the geographic area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador currently served by the 709 area code. The area code 709 consists of 211 Exchange Areas serving the province of Newfoundland and Labrador which includes the major communities of Corner Brook, Gander, Grand Falls, Happy Valley – Goose Bay, Labrador City – Wabush, Marystown and St. -

Regional News

REGIONAL FIS E IES NEWS J liaRY 1970 ( 1 • Mdeit,k40 111.111111111...leit 9 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES OF CANADA NEWFOUNDLAND REGION REDUCTION PLANT OFFICIALLY OPENED The ne3 3/4-million NATLAKE herring reduction plant at Burgeo was officially opened January 28th by Premier J. R. Smallwood. Among special guests attending the opening ceremonies were: federal Transport Minister Don Jamieson, provincial Minister of Fisheries A. Maloney and our Regional Director, H. R. Bradley. Privately financed, the new plant is a joint effort of Spencer Lake, the Clyde Lake Group and National Sea Products of Nova Scotia. Ten herring seiners from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and British Columbia are under contract to land catches at the plant. Fifty people will be employed as production workers at the plant which will operate on a 21-hour, three shift basis. - 0 - 0 - 0 - ATTEND CAMFI CONFERENCE Four representatives of Regional Headquarters staff are attending the Conference on Automation and Mechanization in the Fishing Industry being held in Montreal February 3 - 6. The conference is sponsored by the Federal-Provincial Atlantic Fisheries Committee which is comprised of the deputy ministers responsible for fisheries in the Federal Government and the governments of Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The Secretariat for the conference was provided by the Industrial Development Service, Department of Fisheries and Forestry, Ottawa. Attending the conference from the Newfoundland. Region were: J. P. Hennessey, R. n. Prince, m. Barnes and E. B. Dunne. ****** ****** FROZEN TROUT RETURN TO LIFE A true story told by Bob Ebsary, a former technician with our Inspection Laboratory, makes one wonder whether or not trout, like cats, have nine lives. -

Trinity Bay North, Little Catalina and the Cabot Loop Municipal Service Sharing Case Study

Trinity Bay North, Little Catalina and the Cabot Loop Municipal Service Sharing Case Study Prepared by Kelly Vodden on behalf of the Community Cooperation Resource Centre, Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Municipalities With special thanks to all participating communities for sharing their stories July 2005 Table of Contents Municipal Service Sharing Overview ..............................................................................................3 General Characteristics of the Region..............................................................................................4 Shared Services ................................................................................................................................5 1. Amalgamation (joint services/administration).........................................................................5 2. Animal control..........................................................................................................................8 3. Economic development/tourism...............................................................................................8 4. Fire protection ........................................................................................................................10 5. Joint Council ..........................................................................................................................13 6. Recreation...............................................................................................................................14 -

This Guide Was Prepared and Written by Roberta Thomas, Contract Archivist, During the Summer of 2000

1 This guide was prepared and written by Roberta Thomas, contract archivist, during the summer of 2000. Financial assistance was provided by the Canadian Council of Archives, through the Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Archives. This guide was updated by Pamela Hayter, October 6, 2010. This guide was updated by Daphne Clarke, February 8, 2018. Clarence Dewling, Archivist TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 List of Holdings ........................................................ 3 Business Records ...................................................... 7 Church and Parish Records .................................... 22 Education and Schools…………………………..52 Courts and Administration of Justice ..................... 65 Societies and Organizations ................................... 73 Personal Papers ..................................................... 102 Manuscripts .......................................................... 136 Index……………………………………………2 LIST OF THE HOLDINGS OF THE TRINITY 3 HISTORICAL SOCIETY ARCHIVES BUSINESS RECORDS Slade fonds, 1807-1861. - 84 cm textual records. E. Batson fonds, 1914 – 1974 – 156.40 cm textual records Grieve and Bremner fonds, 1863-1902 (predominant), 1832-1902 (inclusive). - 7.5 m textual records Hiscock Family Fonds, 1947 – 1963 – 12 cm textual records Ryan Brothers, Trinity, fonds, 1892 - 1948. – 6.19 m textual records Robinson Brooking & Co. Price Book, 1850-1858. - 0.5 cm textual records CHURCH AND PARISH RECORDS The Anglican Parish of Trinity fonds - 1753 -2017 – 87.75 cm textual records St. Paul=s Anglican Church (Trinity) fonds. - 1756 - 2010 – 136.5 cm textual records St. Paul’s Guild (Trinity) ACW fonds – 1900 – 1984 – 20.5 cm textual records Church of the Holy Nativity (Little Harbour) fonds, 1931-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. Augustine=s Church (British Harbour) fonds, 1854 - 1968. - 9 cm textual records St. Nicholas Church (Ivanhoe) fonds, 1926-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. George=s Church (Ireland=s Eye) fonds, 1888-1965. -

Cursillo Parish Contacts

Anglican Diocese of Central Newfoundland Cursillo Parish Contacts Mailing Name Phone # Email Address Parish Address General Delivery Minnie Janes 536-3247 Badger’s Quay Badger’s Quay, NL A0G 1B0 POBox 942 545-2105 Edith Bagg [email protected] Bonavista Bonavista, NL A0C 1B0 470-0431 General Delivery Wilson & Stella Mills 656-4481 [email protected] Gander Bay Boyd’s Cove, NL A0G 1G0 POBox 59 Geraldine Purchase 672-3503 Buchans Buchans, NL A0H 1G0 POBox 45 June Holloway [email protected] Smith's Sound Port Blandford, NL A0C2G0 POBox 310 Rev. Terry Caines 891-1377 Burin Burin, NL A0G1E0 24 Park Avenue Elsie Sullivan 466-2002 [email protected] Clarenville Clarenville, NL A5A 1V8 POBox 111 Garry & Dallas Mitchell 884-5319 Twillingate Durrell, NL A0G1Y0 POBox 85 Gordon & Thelma Davidge 888-3336 [email protected] Belleoram English Harbour W, NL A0H 1M0 General Delivery Judy Mahoney Fogo Island Fogo, NL A0G 2B0 POBox 398 Jean Rose 832-2297 Fortune/Lamaline Fortune, NL A0E 1P0 POBox 391 Jean Eastman 674-5213 [email protected] Gambo Gambo, NL A0G 1T0 113 Ogilvie Street John & Beryl Barnes 256-8184 Gander Gander, NL A1V 2R2 POBox 24 Herbert & Beulah Ralph 533-2567 Glovertown Glovertown South, NL A0G 2M0 POBox 571 Winston & Shirley Walters 832-1930 [email protected] Grand Bank Grand Bank, NL A0E 1W0 20 Dunn Place Robert & Thelma Stockley 489-6945 [email protected] Grand Falls GrandFalls-Windsor, NL A2A2M3 8 Dorrity Place Ed & Glenda Warford 489-6747 [email protected] Windsor GrandFalls-Windsor, -

Rental Housing Portfolio March 2021.Xlsx

Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Private Sector Non Profit Adams Cove 1 1 Arnold's Cove 29 10 39 Avondale 3 3 Bareneed 1 1 Bay Bulls 1 1 10 12 Bay Roberts 4 15 19 Bay de Verde 1 1 Bell Island 90 10 16 116 Branch 1 1 Brigus 5 5 Brownsdale 1 1 Bryants Cove 1 1 Butlerville 8 8 Carbonear 26 4 31 10 28 99 Chapel Cove 1 1 Clarke's Beach 14 24 38 Colinet 2 2 Colliers 3 3 Come by Chance 3 3 Conception Bay South 36 8 14 3 16 77 Conception Harbour 8 8 Cupids 8 8 Cupids Crossing 1 1 Dildo 1 1 Dunville 11 1 12 Ferryland 6 6 Fox Harbour 1 1 Freshwater, P. Bay 8 8 Gaskiers 2 2 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Goobies 2 2 Goulds 8 4 12 Green's Harbour 2 2 Hant's Harbour 0 Harbour Grace 14 2 6 22 Harbour Main 1 1 Heart's Content 2 2 Heart's Delight 3 12 15 Heart's Desire 2 2 Holyrood 13 38 51 Islingston 2 2 Jerseyside 4 4 Kelligrews 24 24 Kilbride 1 24 25 Lower Island Cove 1 1 Makinsons 2 1 3 Marysvale 4 4 Mount Carmel-Mitchell's Brook 2 2 Mount Pearl 208 52 18 10 24 28 220 560 New Harbour 1 10 11 New Perlican 0 Norman's Cove-Long Cove 5 12 17 North River 4 1 5 O'Donnels 2 2 Ochre Pit Cove 1 1 Old Perlican 1 8 9 Paradise 4 14 4 22 Placentia 28 2 6 40 76 Point Lance 0 Port de Grave 0 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Portugal Cove/ St. -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

Workplan Plan

Town of Port Rexton Initial Community Workplan 2018 4.1. Committee Direction .................................................... 21 Table of Contents 4.2. Design Parameters and Guidelines .............................. 22 1. Land Ownership ..................................................................... 3 4.3. Building Design ............................................................. 24 1.1. Committee Direction ...................................................... 3 5. Visitor Parking ...................................................................... 25 1.2. Macro-Analysis of Land Ownership ............................... 4 5.1. Committee Direction .................................................... 25 1.3. Land Ownership of Selected Area of Interest ................ 5 5.2. Parking Design .............................................................. 25 2. Housing and Attraction of New Residents ............................. 7 6. In-Town Trails ....................................................................... 26 2.1. Committee Direction ...................................................... 7 6.1. Committee Direction .................................................... 26 2.2. Attraction of New Residents .......................................... 8 7. Entrepreneur/Business Attraction ....................................... 27 2.3. Low Cost Housing Development .................................... 8 7.1. Committee Direction .................................................... 27 2.4. The Housing Continuum................................................ -

Private Sector Non Profit Adams Cove 1 1 Arnold's Cove 29 10 39

Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2020 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Private Sector Non Profit Adams Cove 1 1 Arnold's Cove 29 10 39 Avondale 3 4 7 Bareneed 1 1 Bay Bulls 1 1 10 12 Bay Roberts 0 1 15 16 Bay de Verde 1 1 Bell Island 89 10 16 115 Branch 1 1 Brigus 5 5 Brownsdale 1 1 Bryants Cove 1 1 Butlerville 8 8 Carbonear 26 4 31 10 28 99 Chapel Cove 1 1 Clarke's Beach 14 24 38 Colinet 2 2 Colliers 3 3 Come by Chance 3 3 Conception Bay South 36 10 14 3 16 79 Conception Harbour 8 8 Cupids 8 8 Cupids Crossing 1 1 Dildo 1 1 Dunville 11 11 Ferryland 6 6 Fox Harbour 1 1 Freshwater, P. Bay 8 8 Gaskiers 2 2 Goobies 2 2 Goulds 8 4 12 Green's Harbour 2 2 Harbour Grace 14 1 16 31 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2020 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Harbour Main 1 1 Heart's Content 2 2 Heart's Delight 3 14 17 Heart's Desire 2 2 Holyrood 13 38 51 Islingston 0 Jerseyside 4 4 Kelligrews 30 30 Kilbride 1 1 Lower Island Cove 1 1 Makinsons 2 1 3 Marysvale 4 4 Mount Carmel-Mitchell's Brook 2 2 Mount Pearl 208 55 24 10 24 52 220 593 New Harbour 1 7 8 New Perlican 0 Norman's Cove-Long Cove 5 12 17 North River 4 1 5 O'Donnels 2 2 Ochre Pit Cove 1 1 Old Perlican 1 8 9 Paradise 3 44 4 51 Placentia 28 2 6 40 76 Point Lance 0 Port de Grave 0 Portugal Cove/ St. -

Strategic Plan 2018

Town of Port Rexton Strategic Plan 2018 Programs and Services for Residents of All Ages ......................... 21 Table of Contents 13. Recreation Facilities and Programs .............................. 21 Strategic Plan ............................................................................... 1 14. Medical Services ........................................................... 21 Town of Port Rexton ...................................................................... 5 15. Seniors Care Facility ..................................................... 22 Vision .............................................................................................. 7 16. Reduce/Reuse/Recycle ................................................. 22 Mission Statement ......................................................................... 7 Attraction of New Residents ........................................................ 23 Goals and Strategies ...................................................................... 9 17. Marketing Port Rexton ................................................. 23 Community Work Plan ............................................................... 11 18. Sponsorship of Immigrant Families .............................. 24 Strategy A: PlaceBuilding our Town ............................................. 13 19. Affordable Housing Development ................................ 24 Planning ....................................................................................... 14 Strategy B: Strategic Tourism Product Development