Mission Possible by Roland Lazenby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fc Barcellona Lassa

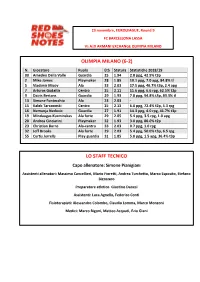

23 novembre, EUROLEAGUE, Round 9 FC BARCELLONA LASSA Vs A|X ARMANI EXCHANGE OLIMPIA MILANO OLIMPIA MILANO (6-2) N. Giocatore Ruolo Età Statura Statistiche 2018/19 00 Amedeo Della Valle Guardia 25 1.94 2.8 ppg, 42.9% t3p 2 Mike James Playmaker 28 1.85 19.1 ppg, 7.0 apg, 84.8% tl 5 Vladimir Micov Ala 33 2.03 17.5 ppg, 46.7% t3p, 2.4 apg 7 Arturas Gudaitis Centro 25 2.11 11.6 ppg, 6.6 rpg, 62.5% t2p 9 Dairis Bertans Guardia 29 1.93 7.8 ppg, 54.8% t3p, 83.3% tl 13 Simone Fontecchio Ala 23 2.03 - 15 Kaleb Tarczweski Centro 25 2.13 6.0 ppg, 72.4% t2p, 5.3 rpg 16 Nemanja Nedovic Guardia 27 1.91 14.3 ppg, 4.0 rpg, 41.7% t3p 19 Mindaugas Kuzminskas Ala forte 29 2.05 5.4 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.0 apg 20 Andrea Cinciarini Playmaker 32 1.93 3.0 ppg, 80.0% t2p 23 Christian Burns Ala-centro 33 2.03 0.7 ppg, 1.0 rpg 32 Jeff Brooks Ala forte 29 2.03 5.4 ppg, 50.0% t3p, 6.5 rpg 55 Curtis Jerrells Play-guardia 31 1.85 5.0 ppg, 1.5 apg, 36.4% t3p LO STAFF TECNICO Capo allenatore: Simone Pianigiani Assistenti allenatori: Massimo Cancellieri, Mario Fioretti, Andrea Turchetto, Marco Esposito, Stefano Bizzozero Preparatore atletico. Giustino Danesi Assistenti: Luca Agnello, Federico Conti Fisioterapisti: Alessandro Colombo, Claudio Lomma, Marco Monzoni Medici: Marco Bigoni, Matteo Acquati, Ezio Giani FC BARCELLONA LASSA (5-3) N. -

Kobe Bryant, Four Others Killed in Helicopter Crash in Calabasas

1/26/2020 Kobe Bryant, four others killed in helicopter crash in Calabasas - Los Angeles Times 1/26/2020 Kobe Bryant, four others killed in helicopter crash in Calabasas - Los Angeles Times Bryant’s death stunned Los Angeles and the sports world, which mourned one of basketball’s LOG IN greatest players. Sources said the helicopter took off from Orange County, where Bryant lived. BREAKING NEWS Kobe Bryant, four others killed in helicopter crash in Calabasas The crash occurred shortly before 10 a.m. near Las Virgenes Road, south of Agoura Road, according to a watch commander for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Four others on board also died. CALIFORNIA Kobe Bryant, four others killed in helicopter crash in Calabasas Bryant excelled at Lower Merion High in Ardmore, Pa., near Philadelphia, winning numerous national awards as a senior before announcing his intention to skip college and enter the NBA draft. He was selected 13th overall by Charlotte in 1996, but the Lakers had already worked out a deal with the Hornets to acquire Bryant before his selection. Bryant impressed Lakers General Manager Jerry West during a pre-draft workout session in Los Angeles. Less than three weeks later, the Lakers traded starting center Vlade Divac to the Hornets in exchange for Bryant’s rights. Bryant, whose favorite team growing up was the Lakers, had to have his parents co-sign his NBA contract because he was 17 years old. The 6-foot-6 guard made his pro debut in the 1996-97 season opener against Minnesota; at the time he was the youngest player ever to appear in an NBA game. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL LAW REVIEW Winter 2012 Vol

NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL LAW REVIEW Winter 2012 Vol. 25, No. 1 Articles Traveling Violation: A Legal Analysis of the Restrictions on the International Mobility of Athletes Mike Salerno ........................................................................................................1 The Nullum Crimen Sine Lege Principle in the Main Legal Traditions: Common Law, Civil Law, and Islamic Law Defining International Crimes Through the Limits Imposed by Article 22 of the Rome Statute Rodrigo Dellutri .................................................................................................37 When Minority Groups Become “People” Under International Law Wojciech Kornacki ..............................................................................................59 Recent Decisions Goodyear Dunlop Tires Operations, S.A. v. Brown .........................................127 The U.S. Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause did not permit North Carolina state courts to exercise in personam jurisdiction over a U.S.-based tire manufacturer’s foreign subsidiaries. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. v. Kirtsaeng ..............................................................131 The Second Circuit extended copyright protection to the plaintiff-appellee’s foreign-manufactured books, which the defendant-appellant imported and resold in the United States, pursuant to a finding that the “first-sale doctrine” does not apply to works manufactured outside of the United States. Sakka (Litigation Guardian of) v. Société Air France -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1640

S1640 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 2, 2006 this special unit of Peace Corp volun- see his wife, the person he loved so ‘‘This was before the 3-point shot, and you teers were also deployed to Sri Lanka much. weren’t allowed to dunk the ball,’’ remem- and Thailand to assist with rebuilding Mr. President, I have only mentioned bered guard Belmont Anderson, now a podia- just a few highlights from the life of trist in Las Vegas. ‘‘He had a Larry Bird tsunami-devastated areas. range with his outside shot. When he’d take Today, I am proud to honor 27 Rhode this great man. I ask unanimous con- it, the coaches would yell, ‘no, no, no . Islanders currently serving in the sent to have printed in the RECORD a good shot, Kresh.’ They frowned on taking Peace Corps. I wish them the very best touching article from the Deseret the long shot because you weren’t rewarded in all their endeavors and I thank them Morning News that summarizes why so for it. Imagine what he’d have done if the 3- for their service to our country in this many of us in Utah are looking forward point shot was in back then or if he was al- important time in history. Their to finally seeing his jersey hang from lowed to dunk.’’ Cosic was famous for leading the fast names are as follows: the Marriott Center’s rafters this break, making a pinpoint pass or doing a Catherine M. Alexander, Courtney E. weekend. jackknife lay-up, tucking in his knees, going Briar, Anthony J. -

Annual Report 2017 Pdf Dokument

www.divac.com [email protected] facebook.com/fondacijadivac twitter.com/fondacijadivac instagram.com/fondacijadivac/ ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ANA AND VLADE DIVAC FOUNDATION CONTENT A WORD FROM THE FOUNDERS 03 2017 IN NUMBERS 04 I SUPPORT IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS AND HUMANITARIAN AID 05 SUPPORT TO REFUGEES AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES 05 AID THAT CHANGES LIFE 09 SUPPORT TO SINGLE - PARENT FAMILIES 12 DECENT LIFE FOR ALL 12 II ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT AND EMPLOYMENT 13 AGRICULTURE - A STAKE FOR THE FUTURE 13 THE FUTURE LIES IN GOOD IDEAS 14 III DEMOCRACY AND SUPPORT TO LOCAL COMMUNITIES 15 YOUNG PEOPLE CHANGE THE WORLD 15 THE CHANCE LIES IN EDUCATION 16 BABIES ARE IN 16 HELP ON THE ROUTE 18 IV DEVELOPMENT OF PHILANTHROPY 19 CELEBRATING SOLIDARITY 19 PHILANTROPIC COMMUNITY IN ACTION 20 FINANCIAL REPORT 22 2017 COOPERATION WITH BOOKING AND AMAZON 23 LET US HELP THE MOST VULNERABLE ONES 24 REPORT ANNUAL 01 A WORD FROM THE FOUNDERS Challenges, regardless of whether they are Summing up the ten-year results of our big or small, are an integral part of each work has not only filled our hearts with joy, and every person’s life. Unfortunately, not but also strongly motivated us to continue everyone has the same starting point, same our work and make our society a better place opportunities and chances, or the power to live in. Such results would certainly not to overcome problems. Sometimes it is – have been achieved without the dedicated enough to help people get started and take work and expertise of all the employees of control of their lives. -

This Day in Hornets History

THIS DAY IN HORNETS HISTORY January 1, 2005 – Emeka Okafor records his 19th straight double-double, the longest double-double streak by a rookie since 12-time NBA All-Star Elvin Hayes registered 60 straight during the 1968-69 season. January 2, 1998 – Glen Rice scores 42 points, including a franchise-record-tying 28 in the second half, in a 99-88 overtime win over Miami. January 3, 1992 – Larry Johnson becomes the first Hornets player to be named NBA Rookie of the Month, winning the award for the month of December. January 3, 2002 – Baron Davis records his third career triple-double in a 114-102 win over Golden State. January 3, 2005 – For the second time in as many months, Emeka Okafor earns the Eastern Conference Rookie of the Month award for the month of December 2004. January 6, 1997 – After being named NBA Player of the Week earlier in the day, Glen Rice scores 39 points to lead the Hornets to a 109-101 win at Golden State. January 7, 1995 – Alonzo Mourning tallies 33 points and 13 rebounds to lead the Hornets to the 200th win in franchise history, a 106-98 triumph over the Boston Celtics at the Hive. January 7, 1998 – David Wesley steals the ball and hits a jumper with 2.2 seconds left to lift the Hornets to a 91-89 win over Portland. January 7, 2002 – P.J. Brown grabs a career-high 22 rebounds in a 94-80 win over Denver. January 8, 1994 – The Hornets beat the Knicks for the second time in six days, erasing a 20-2 first quarter deficit en route to a 102-99 win. -

O Basquetebol Masculino Nos Jogos Olímpicos: História E a Participação Do Brasil

O BASQUETEBOL MASCULINO NOS JOGOS OLÍMPICOS: HISTÓRIA E A PARTICIPAÇÃO DO BRASIL doi 10.11606/9788564842359 DANTE DE ROSE JUNIOR UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Reitor Prof. Dr. Marco Antonio Zago Vice-Reitor Prof. Dr. Vahan Agopyan Pró-Reitora de Graduação Prof. Dr. Antonio Carlos Hernandes Pró-Reitor de Pós-Graduação Prof. Dr. Carlos Gilberto Carlotti Junior Pró-Reitor de Pesquisa Prof. Dr. José Eduardo Krieger Pró-Reitora de Cultura e Extensão Universitária Prof. Dr. Marcelo de Andrade Roméro ESCOLA DE ARTES, CIÊNCIAS E HUMANIDADES Diretor Profa. Dra. Maria Cristina Motta de Toledo Vice-Diretor Profa. Dra. Neli Aparecida de Mello-Théry Escola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades; Dante De Rose Junior Rua Arlindo Bettio, 1000 Vila Guaraciaba, São Paulo (SP), Brasil CEP: 03828-000 Dante de Rose Junior Editoração / Capa Ademilton J. Santana DADOS INTERNACIONAIS DE CATALOGAÇÃO-NA-PUBLICAÇÃO (Universidade de São Paulo. Escola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades. Biblioteca) De Rose Junior, Dante O basquetebol masculino nos Jogos Olímpicos [recurso eletrônico]: história e a participação do Brasil / Dante De Rose Junior. – São Paulo : Escola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades, 2017 1 recurso eletrônico Modo de acesso ao texto em pdf: <http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/9788564842359> ISBN 978-85-64842-35-9 (Documento eletrônico) 1. Basquetebol. 2. Basquetebol – Aspectos históricos. 3. Jogos Olímpicos. 4. Basquetebol – Brasil. 5. História do esporte. I. Título CDD 22. ed. – 796.323 É permitida a reprodução parcial ou total desta obra, desde que citada a fonte e autoria. -

Milano-Barcellona Game Notes

EUROLEAGUE-ROUND 4 OCTOBER 24 2017-9.00 pm (ita) A|X ARMANI EXCHANGE F.C. BARCELLONA A|X ARMANI EXCHANGE MILANO (0-3) N. Giocatore Età Altezza Ruolo Statistiche EuroLeague 0 Andrew Goudelock 28 1.91 Guardia 15.3 ppg, 52.2% t2p, 3.0 rpg 5 Vladimir Micov 32 2.01 Ala 15.3 ppg, 4.7 rpg, 58.3% t3p 7 Davide Pascolo 27 2.03 Ala forte - 9 Mantas Kalnietis 31 1.95 Playmaker 4.0 ppg, 2.7 apg, 50.0% t3p 13 Simone Fontecchio 22 2.03 Ala - 15 Kaleb Tarczewski 24 2.13 Centro 4.3 ppg, 4.7 rpg, 83.3% tl 20 Andrea Cinciarini 31 1.90 Playmaker - 22 Marco Cusin 32 2.11 Centro 0.3 ppg, 1.0 stop. 23 Awudu Abass 24 2.00 Ala - 24 Amath M’Baye 28 2.06 Ala forte 9.3 ppg, 57.1% t2p, 60.0% t3p 25 Jordan Theodore 28 1.83 Playmaker 10.7 ppg, 6.0 apg 28 Patric Young (i) 25 2.09 Centro - 34 Cory Jefferson 27 2.06 Ala-centro - 45 Dairis Bertans 28 1.93 Guardia 13.0 ppg, 63.6% t2p, 53.8% t3p 77 Arturas Gudaitis 24 2.11 Centro 14.3 ppg, 73.3% t2p, 4.3 rpg Capo allenatore: SIMONE PIANIGIANI Assistenti Allenatori: Massimo Cancellieri, Mario Fioretti, Marco Esposito, Stefano Bizzozero. Preparatore Atletico: Giustino Danesi, Luca Agnello (assistente) F.C. BARCELLONA (1-2) N. Giocatore Età Altezza Ruolo Statistiche EuroLeague 1 Kevin Seraphin 27 2.08 Centro 17.7 ppg, 78.6% t2p, 4.7 rpg 5 Pau Ribas 30 1.94 Guardia 6.0 ppg, 2.3 rpg, 2.3 apg 6 Marc Garcia 21 1.96 Guardia 5.0 ppg 8 Phil Pressey 26 1.80 Playmaker 4.0 ppg, 2.3 apg, 2.0 rpg 9 Adam Hanga 28 2.01 Ala piccola 11.7 ppg, 61.1% t2p, 4.0 rpg 11 J.Carlos Navarro 37 1.92 Guardia 2.0 ppg, 2.0 apg 13 Thomas Heurtel 28 1.89 -

Episode 6: Drazen Petrovic and Basketball’S Cold War

Death at the Wing Episode 6: Drazen Petrovic and Basketball’s Cold War ⧫ ⧫ ⧫ Back in 1988, the USA Men’s Basketball team did something they almost never did... ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: The United States found themselves in a position in the last seven minutes of this game of having to score on almost every possession and they could not. After winning 9 of the last 10 Olympics they competed in, they lost. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: But there’s no time, really, for even a miracle now. And the Soviets are already celebrating. The USA suddenly found itself wearing bronze. It did not go over well. And so, as the dust settled, they decided to do what America does best: get better through hard work, inch by inch, grinding it out… I’m kidding. No, we did the real American thing. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: What may well be the best basketball team ever assembled… ...which is throwing lots of money at something to make even more money. And so, for the next Olympics, they formed a super squad of sorts. No more amateurs. It was time to bend the rules a little bit and bring in the pros. And, of course, bring in Reebok to sponsor it. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: And now, the United States of America. This was the Dream Team. Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Michael Jordan. This wasn’t about winning gold. This was about buying the whole fucking gold mine. Shock and awe. 1 But in Barcelona in 1992, one player in all of the Olympics didn’t get the memo... or fax. -

MEDIA GUIDE VLADE DIVAC GENERAL MANAGER Vlade Divac Enters His Sixth Season at the Kings, His Fifth As General Manager

2019-20 PRESEASON MEDIA GUIDE VLADE DIVAC GENERAL MANAGER Vlade Divac enters his sixth season at the Kings, his fifth as General Manager. He joined the Kings on March 3, 2015 as the team’s vice president of basketball and franchise operations and was named General Manager on August 31, 2015. One of the most respected and revered individuals in franchise history, Divac returns to Sacramento having spent more than a decade serving the NBA and international sporting communities with the same distinction that solidified his reputation as a consummate teammate, player, humanitarian and overall difference-maker on and off the basketball court. Divac has served in a variety of administrative and leadership roles since retiring from professional basketball in 2007. In addition to his philanthropic efforts focused on helping children in his native country and other reaches of the globe, he was named President of the Serbian Olympic Committee in 2009. Under his guidance, Serbian athletes have enjoyed greater success and the country is experiencing a resurgence on the international stage. In 16 NBA campaigns with Los Angeles, Charlotte and Sacramento, Divac averaged 11.8 points, 8.2 rebounds, 3.1 assists, 1.1 steals, and 1.4 blocks per game over 1,134 contests. He is only one of four players in league annals to accrue at least 13,000 points, 9,000 rebounds, 3,000 assists, 1,200 steals and 1,600 blocked shots, joining Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Hakeem Olajuwon and Kevin Garnett with that distinction. His six seasons in a Kings uniform marked the most successful period in team history, including a league-high 61 wins in 2001-02 and a trip to the Western Conference Finals.