NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL LAW REVIEW Winter 2012 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fc Barcellona Lassa

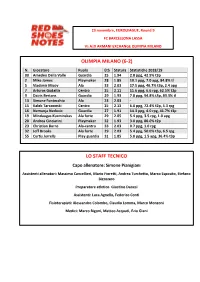

23 novembre, EUROLEAGUE, Round 9 FC BARCELLONA LASSA Vs A|X ARMANI EXCHANGE OLIMPIA MILANO OLIMPIA MILANO (6-2) N. Giocatore Ruolo Età Statura Statistiche 2018/19 00 Amedeo Della Valle Guardia 25 1.94 2.8 ppg, 42.9% t3p 2 Mike James Playmaker 28 1.85 19.1 ppg, 7.0 apg, 84.8% tl 5 Vladimir Micov Ala 33 2.03 17.5 ppg, 46.7% t3p, 2.4 apg 7 Arturas Gudaitis Centro 25 2.11 11.6 ppg, 6.6 rpg, 62.5% t2p 9 Dairis Bertans Guardia 29 1.93 7.8 ppg, 54.8% t3p, 83.3% tl 13 Simone Fontecchio Ala 23 2.03 - 15 Kaleb Tarczweski Centro 25 2.13 6.0 ppg, 72.4% t2p, 5.3 rpg 16 Nemanja Nedovic Guardia 27 1.91 14.3 ppg, 4.0 rpg, 41.7% t3p 19 Mindaugas Kuzminskas Ala forte 29 2.05 5.4 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.0 apg 20 Andrea Cinciarini Playmaker 32 1.93 3.0 ppg, 80.0% t2p 23 Christian Burns Ala-centro 33 2.03 0.7 ppg, 1.0 rpg 32 Jeff Brooks Ala forte 29 2.03 5.4 ppg, 50.0% t3p, 6.5 rpg 55 Curtis Jerrells Play-guardia 31 1.85 5.0 ppg, 1.5 apg, 36.4% t3p LO STAFF TECNICO Capo allenatore: Simone Pianigiani Assistenti allenatori: Massimo Cancellieri, Mario Fioretti, Andrea Turchetto, Marco Esposito, Stefano Bizzozero Preparatore atletico. Giustino Danesi Assistenti: Luca Agnello, Federico Conti Fisioterapisti: Alessandro Colombo, Claudio Lomma, Marco Monzoni Medici: Marco Bigoni, Matteo Acquati, Ezio Giani FC BARCELLONA LASSA (5-3) N. -

Alp(LK)26 3 7 M.Mažvydo Biblioteka • ------SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 the LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL

,-zo-uvos , Alp(LK)26 3 7 M.Mažvydo biblioteka • ----------------------------------- SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 THE LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL. XCV 2010 DECEMBER - GRUODŽIO 7, NR.24. , DEVYNIASDEŠIMT PENKTIEJI METAI _____________________ LIETUVIŲ TAUTINĖS MINTIES LAIKRAŠTIS MĖNAIČIUOSE - LIETUVOS LAISVĖS KOVOS SĄJŪDŽIO MEMORIALAS Lapkričio 22 d. Miknių- vardai. džio Tarybos posėdyje priim Pėtrėčių sodyboje Mėnaičių Į bunkerio vidų patekti ta deklaracija, kurią pasirašė kaime, Radviliškio rajone, nebus galima, jį lankyto aštuoni posėdžio dalyviai. iškilmingai atidaryta Lietuvos jai galės apžiūrėti iš vir Nė vienas iš aštuonių šią laisvės kovos sąjūdžio šaus, įėję į atstatytą klėtį. istorinę deklaraciją pasira Tarybos 1949 m. vasario 16 Bunkerio viršus uždengtas šiusių signatarų neišdavė d. Nepriklausomybės deklara stiklu. Ekspozicijoje - restau juos saugojusių ir globoju cijos paskelbimo memorialas. ruoti partizanų daiktai, eks sių žmonių ir savo idealų. Memorialą, kurį sudaro ponatai iš Šiaulių „Aušros“ Deja, nė vienas legendinės atstatytas Lietuvos partizanų muziejaus ir Genocido aukų partizanų Deklaracijos si vyriausiosios vadavietės bun muziejaus fondų. gnataras laisvės nesulaukė. keris, virš jo esanti klėtis ir Istorija mena, kad Lietuva Nežinoma, kur ilsisi jų palai šalia bunkerio pastatytas pa ginklu priešintis sovietinei kai, todėl tikimasi, kad tin minklas, pašventino Lietuvos okupacijai pradėjo 1944 m. kamai sutvarkyta ši Lietuvai kariuomenės ordinaras vys ir ši kova tęsėsi iki 1953 m., svarbi istorinė vieta taps ne kupas Gintaras Grušas. kai buvo sunaikintos orga tik 1949 m. vasario 16-osios Memorialo atidarymo iš nizuotos Lietuvos partizanų deklaraciją pasirašiusių par kilmėse dalyvavo prezidentė pajėgos. tizanų atminimo ženklu, bet Dalia Grybauskaitė, kraš 1949 m. vasario 2-22 die ir amžinos pagarbos visų to apsaugos ministrė Rasa nomis Mėnaičių kaime buvo Lietuvos partizanų laisvės Juknevičienė, kariuomenės sušauktas visos Lietuvos siekiams simboliu. -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

FIP, Il Commissario È Dino Meneghin the GOLDEN BOY La Giba Per LE

Periodico bimestrale di notizie, informazioni e news dell‘AssociAzione GiocAtori BAsket e del Fondo di Fine CarrierA NumerO 1 · SettembrE/ottobrE 2008 THE GOLDEN BOY Danilo, nuova stella NBA La GIBa PEr LE GIOcaTrIcI La testimonianza di Chicca Macchi ImparIamo Da lorO Marco Calamai racconta la sua esperienza cestistica con i disabili mentali Cambio FIP, il commissario è Dino Meneghin di rotta L`editoriale Coscienza di classe di Giuseppe Cassì Salutiamo con soddisfazione l’usci- ria portatrice di diritti e doveri quindi imprimere una svolta alla CONTROPIEDI PIÙ VELOCI. CANESTRI PIÙ SPETTACOLARI. ta del GIBA Press, che ha subito particolari. I giocatori mostrano gestione federale, ed introdurre un restyling completo per essere sempre più interesse verso le que- uno stile ed un modus operan- ancora più vicino ai giocatori, stioni “politiche” ed intendono par- di dai quali poi difficilmente si per fornire loro informazioni tecipare ogni qualvolta si assumo- potrà tornare indietro alla vec- utili, per raccontare storie im- no decisioni che li riguardano. Di chia politica dei localismi e delle portanti, per contribuire a mi- tutto ciò si dovrà tenere conto nel contrapposizioni personalistiche. gliorare un movimento che sta panorama politico che si va a deli- Tutte le componenti sono chiama- vivendo momenti difficili. neare. Nel prossimo consesso te ad uno sforzo di comprensione nazionale i rappresentanti de- delle aspettative delle altre, avendo SDurante la gestione Maifredi, di- gli atleti dovranno essere tutti a mente l’interesse del movimento nanzi ad interessi contrapposti tra realmente riferibili al movi- nel suo insieme, ed i giocatori non atleti e club, le scelte federali han- mento dei giocatori, e non scelti si sottrarranno al senso di respon- no in genere premiato le istanze dall’alto, dal “palazzo”, in base ad sabilità richiesto. -

2019-20 Panini Flawless Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals 281 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only **Totals do not include 2018/19 Extra Autographs TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 177 177 177 Aaron Gordon 141 141 141 Aaron Holiday 112 112 112 Admiral Schofield 77 77 77 Adrian Dantley 115 115 59 56 Al Horford 385 386 177 169 39 1 Alex English 177 177 177 Allan Houston 236 236 236 Allen Iverson 332 387 295 1 36 55 Allonzo Trier 286 286 118 168 Alonzo Mourning 60 60 60 Alvan Adams 177 177 177 Andre Drummond 90 90 90 Andrea Bargnani 177 177 177 Andrew Wiggins 484 485 118 225 141 1 Anfernee Hardaway 9 9 9 Anthony Davis 453 610 118 284 51 157 Arvydas Sabonis 59 59 59 Avery Bradley 118 118 118 B.J. Armstrong 177 177 177 Bam Adebayo 92 92 92 Ben Simmons 103 132 103 29 Bill Bradley 9 9 9 Bill Russell 186 213 177 9 27 Bill Walton 59 59 59 Blake Griffin 90 90 90 Bob McAdoo 177 177 177 Bobby Portis 118 118 118 Bogdan Bogdanovic 230 230 118 112 Bojan Bogdanovic 90 90 90 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bradley Beal 93 95 93 2 Brandon Clarke 324 434 59 226 39 110 Brandon Ingram 39 39 39 Brook Lopez 286 286 118 168 Buddy Hield 90 90 90 Calvin Murphy 236 236 236 Cam Reddish 380 537 59 228 93 157 Cameron Johnson 290 291 225 65 1 Carmelo Anthony 39 39 39 Caron Butler 1 2 1 1 Charles Barkley 493 657 236 170 87 164 Charles Oakley 177 177 177 Chauncey Billups 177 177 177 Chris Bosh 1 2 1 1 Chris Kaman -

Basketball WA Amended By: AB 11.12.2020 Responsible Person: AB Scheduled Review Date: Oct 2021 Basketball WA

Document: Rules of Operation Version: 1.0 Managed by: Basketball WA Amended by: AB 11.12.2020 Responsible person: AB Scheduled review date: Oct 2021 Basketball WA NBL1 West – WA State Basketball League RULES OF OPERATION Amended by Adam Bowler, NBL1 West - General Manager on 11.12.2020 WA SBL Rules of Operation 1 Document: Rules of Operation Version: 1.0 Managed by: Basketball WA Amended by: AB 11.12.2020 Responsible person: AB Scheduled review date: Oct 2021 Contents DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION ....................................................................... 7 PART 1 – INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 12 1.1 Management ....................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Aims .................................................................................................................... 12 1.3 Competition Structure ......................................................................................... 12 1.4 Conferences ....................................................................................................... 12 1.5 Entry ................................................................................................................... 12 PART 2 – LEAGUE ADMINISTRATION ...................................................................... 14 2.1 Rules of Operation .............................................................................................. 14 2.1.1 Establishment -

Individual Statistical Leaders

Tournament Individual Leaders (as of Aug 14, 2012) All games FIELD GOAL PCT (min. 10 made) FG ATT Pct FIELD GOAL ATTEMPTS G Att Att/G -------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------- Darius Songaila-LTH........... 24 30 .800 Patrick Mills-AUS............. 6 116 19.3 Tyson Chandler-USA............ 14 20 .700 Luis Scola-ARG................ 8 106 13.3 Andre Iguodala-USA............ 14 20 .700 Manu Ginobili-ARG............. 8 103 12.9 Aaron Baynes-AUS.............. 21 32 .656 Kevin Durant-USA.............. 8 101 12.6 Anthony Davis-USA............. 11 17 .647 Pau Gasol-ESP................. 8 100 12.5 Kevin Love-USA................ 34 54 .630 Dan Clark-GBR................. 15 24 .625 FIELD GOALS MADE G Made Made/G Tomofey Mozgov-RUS............ 33 53 .623 --------------------------------------------- LeBron James-USA.............. 44 73 .603 Pau Gasol-ESP................. 8 57 7.1 Serge Ibaka-ESP............... 26 45 .578 Luis Scola-ARG................ 8 56 7.0 Nene Hilario-BRA.............. 12 21 .571 Manu Ginobili-ARG............. 8 51 6.4 Pau Gasol-ESP................. 57 100 .570 Kevin Durant-USA.............. 8 49 6.1 Patrick Mills-AUS............. 6 49 8.2 3-POINT FG PCT (min. 5 made) 3FG ATT Pct 3-POINT FG ATTEMPTS G Att Att/G -------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------- Shipeng Wang-CHN.............. 13 21 .619 Kevin Durant-USA.............. 8 65 8.1 S. Jasikevicius-LTH........... 7 12 .583 Carlos Delfino-ARG............ 8 54 6.8 Dan Clark-GBR................. 8 14 .571 Patrick Mills-AUS............. 6 48 8.0 Andre Iguodala-USA............ 5 9 .556 Carmelo Anthony-USA........... 8 46 5.8 Amine Rzig-TUN................ 8 15 .533 Manu Ginobili-ARG............. 8 43 5.4 Kevin Durant-USA............. -

Similarities and Differences Among Continental Basketball Championships

RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte doi:10.5232/ricyde Rev. int. cienc. deporte RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte VOLUME XIV - YEAR XIV Pages:42-54 ISSN:1 8 8 5 - 3 1 3 7 https://doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2018.05104 Issue: 51 - January - 2018 Basketball without borders? Similarities and differences among Continental Basketball Championships ¿Baloncesto sin fronteras? Similitudes y diferencias entre los Campeonatos Continentales de baloncesto Sergio José Ibáñez1, Sergio González-Espinosa1, Sebastián Feu2 & Javier García-Rubio3 1.Facultad de Ciencias del Deporte. Universidad de Extremadura. Spain 2.Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Extremadura. Spain 3.Facultad de Educación. Universidad Autónoma de Chile. Chile Abstract The analysis of technical-tactical performance indicators is an excellent tool for coaches, because it provides objective informa- tion on the actions of players and teams. The aim of this investigation was to study the performance indicators for the last con- tinental basketball championships. Five continental championships played in 2015 were analysed for a total of 213 matches. The variables analysed were: ball possessions, point difference, points scored, one, two and three point throws attempted and sco- red, total and defensive and offensive rebounds, assists, steals, turnovers, blocks for and against, fouls committed and received, and evaluation. A descriptive analysis and performance profiles were carried out to characterise the sample. A one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni correction were used to identify the differences among championships. A discriminant analysis was performed to identify the performance indicators best characterising each analysed championship. The results show that there are differences among all the championships and all the performance indicators, except in three point throws scored and blocks. -

Letterhead Final

Black Men, Sports and Social Justice The Blueprint Virtual Town Hall September 29, 2020 Transcript Speaker: Chris Broussard Moderation: Kenneth Braswell Kenneth Braswell (00:15): Hey everybody we back to the Blueprint, Re-Imagining the Narrative of the Modern Black Father. We've had a great day so far. Many speakers and panelists continuing to elevate the conversation of Black men and fatherhood and the families that are impacted by their health and wellbeing. We have an awesome interview and conversation coming up with you now with a good friend of mine, Chris Broussard. He is the founder of the organization K.I.N.G. He is also on Fox Sports. He is the co-host of the Odd Couple with Rob Parker. You can also see him almost every day on Undisputed with Shannon and Skip Bayless. How are you doing Chris? Chris Broussard (01:02): I'm great, man. How are you? Kenneth Braswell (01:04): I can't complain at all. I was talking to somebody and telling them that I did a quick shift on Chris because we were going to talk about K.I.N.G, and brothers, and Black fatherhood, and faith. Then I was just compelled to kind of switch on them. But because of that switch I do want to give you the opportunity, and I want to touch on this just a little bit. Talk to us a little bit about K.I.N.G and why you founded K.I.N.G and the work that you're doing today within K.I.N.G. -

CRS Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

96-790 F Updated June 16, 1998 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Kosovo and U.S. Policy Steven Woehrel Specialist in European Affairs Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division Summary Kosovo, a region in southern Serbia, has been the focal point of bitter struggles between Serbs and Albanians for centuries. Leaders of the ethnic Albanian majority in Kosovo say their people will settle for nothing less than complete independence for their region, while almost all Serb political leaders have been adamantly opposed to Kosovo’s independence or even a substantial grant of autonomy to Kosovo. Conflict between ethnic Albanian rebels and Serb police has resulted in over 300 deaths since late February 1998. The United States has spoken out repeatedly against human rights abuses in Kosovo, but does not support Kosovar demands for independence, only an "enhanced status" within the Serbia-Montenegro (the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) that would include meaningful self-administration. The United States and its allies in the international Contact Group (the United States, Russia, Germany, France, Britain and Italy) have used a "carrot-and-stick" approach of sanctions and inducements to stop Serb attacks against civilians and get the two sides to the negotiating table. NATO is reportedly examining options to use force against Serbia-Montenegro if diplomacy and sanctions fail. This report will be updated as events warrant. Background Kosovo, a region in southern Serbia, has a population of 2 million and is one of the poorest regions of the former Yugoslavia.1 It has been the focal point of bitter struggles between Serbs and Albanians for centuries. -

Fundación Nº Magazine 50

Nº 50 • II-2015 CORAZÓN CLASSIC MATCH 2015 TOGETHER FOR SOLIDARITY 01 PORTADA 50 ING.indd 1 7/8/15 13:57 Use the code: E290501 and get a 10% discount* COMBINE YOUR PASSIONS We have 5,450 oces in 165 countries and the best fleet on the market. Travelling with your equipment is now easier and more comfortable than ever. 902 135 531 avis.es Available at Travel Agencies *Oer valid until end of 2015, for any vehicle group, in mainland Spain or in the Balearic or Canary Islands. Oer subject to vehicle availability. Avis' terms and conditions apply. Avis reserves the right to withdraw the oer at any time. Prices subject to change without prior notification. Contents 4 36 16 44 Report 04 Schools 28 Corazón Classic Match 2015: ‘Your ticket, their future’ Close of the 2014-15 season Campus 10 Luis de Carlos Forum 36 Taking football and basketball to the whole world The 9 Basketball European Cups Basketball 40 Interview 16 - Slaughter visits the Foundation’s Steve McManaman wheelchair basketball school News 18 - Students at adapted schools, in the Final - Real Madrid Foundation holds its Four Charity Golf Tournament Real Madrid heritage 44 - Start of the Amateur Padel Circuit 2015 Real Madrid Basketball: the continent’s most decorated team Training 26 Training course for coaches at the new schools Volunteers 50 in Colombia Join us! Publisher: Real Madrid Communication. Coordinator: Julio Fernández. Director of Communication: Antonio Galeano. Editor-in-chief: Milagros Baztán. Writers: Elena Llamazares, Pablo Publications: David Mendoza. Fernández and Isabel Tutor. Editors: Javier Palomino and Madori Okano. -

Sakharov Prize 1988

Nelson Mandela Sakharov Prize 1988 An icon in the fight against racism, Nelson Mandela led South Africa’s historic transition from apartheid to a racially inclusive democracy and promoted equal opportunities and peace for all. Anatoly Marchenko Sakharov Prize 1988 A former Soviet Union dissident who brought to light the horrific jail conditions of political prisoners, Anatoly Marchenko was nominated by Andrei Sakharov himself. Alexander Dubček Sakharov Prize 1989 A leading figure in the Prague Spring, Alexander Dubček strove for democratic and economic reform. He continued to fight for freedom, sovereignty and social justice throughout his life. Aung San Suu Kyi Sakharov Prize 1990 Former political prisoner Aung San Suu Kyi spearheaded Myanmar’s pro-democratic struggle against the country’s military dictatorship. Adem Demaçi Sakharov Prize 1991 Standing up to the harsh repression of the Serbian regime, the ‘Mandela of the Balkans’ devoted himself to the promotion of tolerance and ethnic reconciliation in Kosovo. Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo Sakharov Prize 1992 The ‘Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo’ led a peaceful resistance movement against the military dictatorship and repression in Argentina in response to the forced disappearance and torture of political opponents. Oslobođenje Sakharov Prize 1993 The journalists of Sarajevo’s Oslobođenje newspaper risked their lives fighting to maintain the unity and ethnic diversity of their country during the war in the former Yugoslavia. Taslima Nasreen Sakharov Prize 1994 Exiled from Bangladesh and Bengal for her secular views, the writer Taslima Nasreen fights against the oppression of women and opposes all forms of religious extremism. Leyla Zana Sakharov Prize 1995 The first Kurdish woman to be elected to the Turkish Parliament, Leyla Zana’s fight for democracy symbolises her people’s struggle for dignity and human rights.