DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE on BELIZE Funded by A.I.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stalking Wild Cats

©2005 Graphic Arts Network, Inc. by Jeff Borg, [email protected] STALKING WILD CATS HEAR JAGUARS ROAR IN COCKSCOMB BASIN Once upon a time in the Cockscomb Basin, poachers hunted the powerful jaguars, loggers cut the mahogany trees, and hurricanes toppled the old-growth canopy. Just 20 years later, the jaguars rule, the trees grow dense, and the only threat that remains is from hurricanes. Today, the five wild cats of Belize — jaguars, jaguarundis, margays, ocelots, and pumas — all thrive under the protection of Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary, established in 1986 as the world’s first jaguar preserve and now home to the world’s largest concentration of wild cats. Nature-lovers also thrive at Cockscomb Basin — a 128,000-acre bowl of pristine rainforest, winding rivers, and scenic waterfalls in Stann Creek District — surrounded by mountain ridges and the looming 3,675-foot Victoria Peak. People flock here to hike, camp, kayak, canoe, tube, and swim. The Belize Audubon Society manages the sanctuary, with a visitor center, Maya craft shop, and accommodations just off Southern Highway at Maya Centre. Well-marked hiking trails lead children, adults, and serious naturalists throughout the terrain. Some paths take visitors on casual strolls along riverbanks. Some pose more muscular challenges. One dry-season route dares hearty hikers to conquer Victoria Peak, a two- day trek finished by climbing up on all fours. Get a permit and take a guide. The trails reward visitors with breathtaking views across the basin, rare bird sightings, and a chance to meet diverse Belizean wildlife. While evidence of jaguars abounds, including their ominous roars, humans rarely get to see these masters of stealth. -

No. 10232 MULTILATERAL Agreement Establishing The

No. 10232 MULTILATERAL Agreement establishing the Caribbean Development Bank (with annexes, Protocol to provide for procedure for amendment of article 36 of the Agreement and Final Act of the Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Caribbean Development Bank). Done at Kingston, Jamaica, on 18 October 1969 Authentic text: English. Registered ex officio on 26 January 1970. MULTILATÉRAL Accord portant création de la Banque de développement des Caraïbes (avec annexes, Protocole établissant la procé dure de modification de l'article 36 de l'Accord et Acte final de la Conférence de plénipotentiaires sur la Ban que de développement des Caraïbes). Fait à Kingston (Jamaïque), le 18 octobre 1969 Texte authentique: anglais. Enregistr d©office le 26 janvier 1970. 218 United Nations Treaty Series 1970 AGREEMENT 1 ESTABLISHING THE CARIBBEAN DEVEL OPMENT BANK The Contracting Parties, CONSCIOUS of the need to accelerate the economic development of States and Territories of the Caribbean and to improve the standards of living of their peoples; RECOGNIZING the resolve of these States and Territories to intensify economic co-operation and promote economic integration in the Caribbean; AWARE of the desire of other countries outside the region to contribute to the economic development of the region; CONSIDERING that such regional economic development urgently requires the mobilization of additional financial and other resources; and CONVINCED that the establishment of a regional financial institution with the broadest possible participation will facilitate -

Species List January 28 – February 6, 2020 | Compiled by Keith Hansen

Guatemala: Nature & Culture With Tikal Extension| Species List January 28 – February 6, 2020 | Compiled by Keith Hansen With Guides Keith Hansen, Patricia Briceño, Roland Rumm and local guide Freddie and participants Julie, Paul, Gwen, Gary, Barbara, Rolande, Brian, Jane, and Debbie. Itinerary Day 1: 1/29/20, Guatemala City. Clarion Hotel to Marroquin University and Textile Museum, to Guatemala Market, to Cocales “Crazy Gas Station” at intersection of CA 12 and 11 to Los Tarrales Natural Reserve. Day 2: 1/30/20, Los Tarrales Nat. Res. into jeeps and up to La Isla vista point. Down for lunch at lodge. Then San Pedro trail and back to La Rinconada lodge, for dinner. Day 3: 1/31/20, Pre-dawn, Volcan Fuego eruption. Los Tarrales, short walk on San Pedro Trail. Breakfast at lodge. Depart and drive to Fuentes Georginia Hot Springs Spa. Lunch with “mega flock”. Depart and drive to Xela (Quetzaltenango). Dinner at Hotel Bonifaz. Day 4: 2/1/20, Split group. One group, (Keith), up at 4:00 AM. Drive to Refugio del Quetzal for Quetzal, then viewing from mirador “overlook”. Then drive to San Rafael for lunch. Then drive back to Xela. Second group, (Patricia) Xela tour. Later some went back to “Owl” at Fuentes Georgino Hot Springs, then back to Xela. Day 5: 2/2/20, Xela breakfast at Hotel, depart for the market at Chichicastenango with stop at Continental Divide at 10,000 feet. To market, then lunch at “Mayan Inn”. Drive to Panajachel at Lago de Atitlan. Boarded a launch to cross the lake to Hotel Bambu, Santiago Atitlan. -

Long-Term Development in Post-Disaster Intentional Communities in Honduras

From Tragedy to Opportunity: Long-term Development in Post-Disaster Intentional Communities in Honduras A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ryan Chelese Alaniz IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ronald Aminzade June 2012 © Ryan Alaniz 2012 Acknowledgements Like all manuscripts of this length it took the patience, love, and encouragement of dozens of people and organizations. I would like to thank my parents for their support, numerous friends who provided feedback in informal conversations, my amazing editor and partner Jenny, my survey team, and the residents of Nueva Esperanza, La Joya, San Miguel Arcangel, Villa El Porvenir, La Roca, and especially Ciudad España and Divina for their openness in sharing their lives and experiences. Finally, I would like to thank Doug Hartmann, Pat McNamara, David Pellow, and Ross MacMillan for their generosity of time and wisdom. Most importantly I would like to express my gratitude to my advisor, Ron, who is an inspiration personally and professionally. I would also like to thank the following organizations and fellowship sponsors for their financial support: the University of Minnesota and the Department of Sociology, the Social Science Research Council, Fulbright, the Bilinski Foundation, the Public Entity Risk Institute, and the Diversity of Views and Experiences (DOVE) Fellowship. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all those who have been displaced by a disaster and have struggled/continue to struggle to rebuild their lives. It is also dedicated to my son, Santiago. May you grow up with a desire to serve the most vulnerable. -

Ethnobotanical and Floristic Research in Belize: Accomplishments, Challenges and Lessons Learned Michael J

Ethnobotanical and Floristic Research in Belize: Accomplishments, Challenges and Lessons Learned Michael J. Balick and Hugh O’Brien Abstract Ethnobotanical and floristic research in Belize was con- Background and Introduction ducted through the Belize Ethnobotany Project which was launched in 1988 as a multi-disciplinary effort of a number Belize is a Central American country located on the Ca- of individuals and institutions in Belize and internationally. ribbean coast, south of Mexico and east of Guatemala. The objectives of the project were the preservation of cul- It has a of population 250,000 inhabitants spread over tural and traditional knowledge, natural products research 8,867 square miles, giving a low population density of 28 (through the National Cancer Institute), technology trans- persons per sq. mile. Over 70% of the country is under fer, institutional strengthening and student training. This natural forest, and protected areas now cover 36 % of the paper discusses the implementation of the project com- land mass. Despite the small size of the country, its eco- ponents, highlighting its accomplishments, challenges systems are varied and its ethnicity diverse, giving rise and lessons learned. A checklist of the flora has been pro- to a rich culture with respect to traditional healing. The duced, and includes 3,408 native and cultivated species ethnic diversity ranges from groups of indigenous Maya found in Belize. The multiple use curve is introduced as a and the Black Caribs (Garinagu), through the Creole de- way of determining the most appropriate sample size for scendants of African slaves, to the more recent Central ethnobotanical interviews/collections. -

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List FCC ITU-T Country Region Dialing FIPS Comments, including other 1 Code Plan Code names commonly used Abu Dhabi 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aden 5 967 YE include with Yemen Admiralty Islands 7 675 PP include with Papua New Guinea (Bismarck Arch'p'go.) Afars and Assas 1 253 DJ Report as 'Djibouti' Afghanistan 2 93 AF Ajman 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area 9 44 AX include with United Kingdom Al Fujayrah 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aland 9 358 FI Report as 'Finland' Albania 4 355 AL Alderney 9 44 GK Guernsey (Channel Islands) Algeria 1 213 AG Almahrah 5 967 YE include with Yemen Andaman Islands 2 91 IN include with India Andorra 9 376 AN Anegada Islands 3 1 VI include with Virgin Islands, British Angola 1 244 AO Anguilla 3 1 AV Dependent territory of United Kingdom Antarctica 10 672 AY Includes Scott & Casey U.S. bases Antigua 3 1 AC Report as 'Antigua and Barbuda' Antigua and Barbuda 3 1 AC Antipodes Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Argentina 8 54 AR Armenia 4 374 AM Aruba 3 297 AA Part of the Netherlands realm Ascension Island 1 247 SH Ashmore and Cartier Islands 7 61 AT include with Australia Atafu Atoll 7 690 TL include with New Zealand (Tokelau) Auckland Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Australia 7 61 AS Australian External Territories 7 672 AS include with Australia Austria 9 43 AU Azerbaijan 4 994 AJ Azores 9 351 PO include with Portugal Bahamas, The 3 1 BF Bahrain 5 973 BA Balearic Islands 9 34 SP include -

Tropical Cyclone Effects on California

/ i' NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS WR-~ 1s-? TROPICAL CYCLONE EFFECTS ON CALIFORNIA Salt Lake City, Utah October 1980 u.s. DEPARTMENT OF I National Oceanic and National Weather COMMERCE Atmospheric Administration I Service NOAA TECHNICAL ME~RANOA National Weather Service, Western R@(Jfon Suhseries The National Weather Service (NWS~ Western Rl!qion (WR) Sub5eries provide! an informal medium for the documentation and nUlck disseminuion of l"'eSUlts not appr-opriate. or nnt yet readY. for formal publication. The series is used to report an work in pronf"'!ss. to rie-tJ:cribe tl!1:hnical procedures and oractice'S, or to relate proqre5 s to a Hmitfd audience. The~J:e Technical ~ranc1i!l will report on investiqations rit'vot~ or'imaroi ly to rl!nionaJ and local orablems of interest mainly to personnel, "'"d • f,. nence wUl not hi! 'l!lidely distributed. Pacer<; I to Z5 are in the fanner series, ESSA Technical Hetooranda, Western Reqion Technical ~-··•nda (WRTMI· naoors 24 tn 59 are i·n the fanner series, ESSA Technical ~-rando, W.othel" Bureou Technical ~-randa (WSTMI. aeqinniM with "n. the oaoers are oa"t of the series. ltOAA Technical >4emoranda NWS. Out·of·print .....,rond1 are not listed. PanfiM ( tn 22, except for 5 {revised erlitinn), ar'l! availabll! froM tt'lt Nationm1 Weattuu• Service Wesurn Ret1inn. )cientific ~•,.,irr• Division, P.O. Box lllAA, Federal RuildiM, 125 South State Street, Salt La~• City, Utah R4147. Pacer 5 (revised •rlitinnl. and all nthei"S beqinninq ~ith 25 are available from the National rechnical Information Sel'"lice. II.S. -

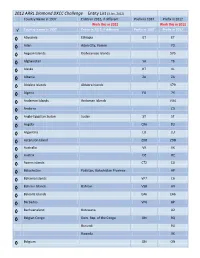

2012 ARRL Diamond DXCC Challenge Entity List

2012 ARRL Diamond DXCC Challenge Entity List (3 Jan, 2012) Country Name in 1937 Entity in 2012, if different Prefix in 1937 Prefix in 2012 Work this in 2012 Work this in 2012 √ Country name in 1937 Entity in 2012, if different Prefix in 1937 Prefix in 2012 ◊ Abyssinia Ethiopia ET ET ◊ Aden Aden City, Yemen 7O ◊ Aegean Islands Dodecanese Islands SV5 ◊ Afghanistan YA T6 ◊ Alaska K7 KL ◊ Albania ZA ZA ◊ Aldabra Islands Aldabra Islands S79 ◊ Algeria FA 7X ◊ Andaman Islands Andaman Islands VU4 ◊ Andorra C3 ◊ Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Sudan ST ST ◊ Angola CR6 D2 ◊ Argentina LU LU ◊ Ascension Island ZD8 ZD8 ◊ Australia VK VK ◊ Austria OE OE ◊ Azores islands CT2 CU ◊ Baluchistan Pakistan, Balochistan Province AP ◊ Bahama Islands VP7 C6 ◊ Bahrein Islands Bahrain VS8 A9 ◊ Balearic islands EA6 EA6 ◊ Barbados VP6 8P ◊ Bechuanaland Botswana A2 ◊ Belgian Congo Dem. Rep. of the Congo ON 9Q Burundi 9U Rwanda 9X ◊ Belgium ON ON ◊ Bermuda Islands VP9 VP9 ◊ Bhutan A5 Bismarck Archipelago Islands off the northeast coast ◊ of Papua New Guinea1 OC-008 Bismarck Archipelago P29 OC-025 Admiralty Islands P29 OC-103 St Matthias Group P29 OC-257 Nuguria Islands P29 OC-258 Coastal Islands North P29 ◊ Bolivia CP CP ◊ Borneo, Netherlands Borneo, Indonesia PK5 YB7 ◊ Brazil PY PY ◊ British Honduras Belize VP1 V3 ◊ British North Borneo Sabah State, Malaysia VS4 9M6 ◊ Brunei V8 ◊ Bulgaria LZ LZ ◊ Burma Myanmar XZ XZ ◊ Cameroons, French Cameroon FE8 TJ ◊ Canada Does not include VO1/VO2 VE VE Canal Zone Any area within 8 km of the NY HP ◊ Panama Canal ◊ Canary Islands EA8 EA8 -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

THE NATIONAL BOTANIC GARDENS, GLASNEVIN and BELIZE BOTANIC GARDENS Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, Vol

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica SAYERS, BRENDAN; DUPLOOY, HEATHER; ADAMS, BRETT WORKING TOGETHER FOR ORCHID CONSERVATION – THE NATIONAL BOTANIC GARDENS, GLASNEVIN AND BELIZE BOTANIC GARDENS Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 153-155 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813030 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 153-155. 2007. WORKING TOGETHER FOR ORCHID CONSERVATION – – THE NATIONAL BOTANIC GARDENS, GLASNEVIN AND BELIZE BOTANIC GARDENS 1,3 2 2 BRENDAN SAYERS , HEATHER DUPLOOY & BRETT ADAMS 1 National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland 2 Belize Botanic Gardens, San Ignacio, Cayo, Belize, Central America 3 Author for correspondence: [email protected] KEY WORDS: Belize, collaboration, capacity building Introduction listed other than the former publication includes Cattleya skinneri Bateman and Oeceoclades macula- The National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin (NBGG) ta (Lindl.) Lindl., excludes Pleurothallis barbulata and the Belize Botanic Gardens (BBG) have been Lindl. and some nomenclature changes. Otherwise by involved in Belizean orchid research since 1997. Staff 2000 the list of species included for Belize totalled from NBGG had travelled to Belize on two prior occa- 279 species. For the purpose of this paper and various sions with the purpose of collecting living specimens statistics within, the authors accept that 279 is the fig- of orchids, bromeliads and cacti, along with seed of ure of the orchid flora in 2000. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas. Alan Knowlton Craig Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Craig, Alan Knowlton, "The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1117. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been „ . „ i i>i j ■ m 66—6437 microfilmed exactly as received CRAIG, Alan Knowlton, 1930— THE GEOGRAPHY OF FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 G eo g rap h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE GEOGRAPHY OP FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State university and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Alan Knowlton Craig B.S., Louisiana State university, 1958 January, 1966 PLEASE NOTE* Map pages and Plate pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best way possible. University Microfilms, Inc. AC KNQWLEDGMENTS The extent to which the objectives of this study have been acomplished is due in large part to the faithful work of Tiburcio Badillo, fisherman and carpenter of Cay Caulker Village, British Honduras.