Lemmon's Holly Fern (Polystichum Lemmonii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WO 2016/061206 Al 21 April 2016 (21.04.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/061206 Al 21 April 2016 (21.04.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: BAUER, Christopher; PIONEER HI-BRED IN C12N 15/82 (2006.01) A01N 65/00 (2009.01) TERNATIONAL, INC., 7100 N.W. 62nd Avenue, John C07K 14/415 (2006.01) ston, Iowa 5013 1-1014 (US). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/US2015/055502 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (22) Date: International Filing BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, 14 October 2015 (14.10.201 5) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (25) Filing Language: English HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, (26) Publication Language: English MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (30) Priority Data: PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 62/064,810 16 October 20 14 ( 16.10.20 14) US SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (71) Applicants: PIONEER HI-BRED INTERNATIONAL, INC. [US/US]; 7100 N.W. -

Typifications and Synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae) from Chile and Argentina

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeys 65: 91–105 (2016)Typifications and synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae)... 91 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.65.8620 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://phytokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Typifications and synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae) from Chile and Argentina Rita E. Morero1,2, David S. Barrington3, Monique A. McHenry3, João P. S. Condack4, Gloria E. Barboza1,2 1 Departamento de Farmacia, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, (UNC), Av. Medina Allende y Haya de la Torre. Ciudad Universitaria, Córdoba. Argentina 2 Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal (IMBIV-CONICET), Casilla de Correo 495, 5000 Córdoba 3 University of Vermont, Pringle Herbarium, Torrey Hall, 27 Colchester Ave, Burlington, VT 05405 4 Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista s.n., São Cristóvão, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 20940-040 Corresponding authors: Rita E. Morero ([email protected]); Gloria E. Barboza ([email protected]) Academic editor: Blanca Leon | Received 24 March 2016 | Accepted 6 June 2016 | Published 30 June 2016 Citation: Morero RE, Barrington DS, McHenry MA, Condack JPS, Barboza GE (2016) Typifications and synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae) from Chile and Argentina. PhytoKeys 65: 91–105. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.65.8620 Abstract Polystichum Roth is one of the largest and most taxonomically challenging fern genera. South American species have a rich and complex nomenclatural history; many of the early names are inadequately typified. Based on extensive examination of original type material, we designate eleven lectotypes (including As- pidium mohrioides, A. montevidense f. imbricata, A. montevidense f. squamulosa, A. -

An Illustrated Key to the Ferns of Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Helen Patricia O'Donahue Pembrook for the Master of Arts (Name) (Degree) Systematic Botany (Major) Date thesis is presented March 8, 1963 Title AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE FERNS OF OREGON Abstract approved IIIII (Major professor) The purpose of the work is to enable students of botany to identify accurately Oregon ferns, both as living plants and as dried speci- mens. Therefore, it provides vegetative keys to the families, genera and species of the ferns (Class FILICINAE) found in Oregon. Correct names have been determined using the latest available information and in accordance with 1961 edition of the International Code of Botan- ical Nomenclature. The synonomy, a description, and original draw- ings of each species and subspecific taxon are included. An illustrated glossary and a technical glossary have been prepared to explain and clarify the descriptive terms used. There is also a bibliography of the literature used in the preparation of the paper. The class FILICINAE is represented in Oregon by 4 families, 20 genera, 45 or 46 species, 4 of which are represented by more than one subspecies or variety. One species, Botrychium pumicola Coville, is endemic. The taxa are distributed as follows: OPHIO- GLOSSACEAE, 2 genera: Botrychium, 7 species, 1 represented by 2 subspecies, 1 by 2 varieties; Ophioglossum, 1 species. POLYPODI- ACEAE, 15 genera: Woodsia., 2 species; Cystopteris, 1 species; Dryopteris, 6 species; Polystichum, 5 species, 1 represented by 2 distinct varieties; Athyrium, 2 species; Asplenium, 2 species; Stru- thiopteris, 1 species; Woodwardia, 1 species; Pitrogramma, 1 spe- cies; Pellaea, 4 species; Cheilanthes, 3 or 4 species; Cryptogramma, 1 species; Adiantum, 2 species; Pteridium, 1 species; Polypodium, 2 species, 1 represented by 2 varieties. -

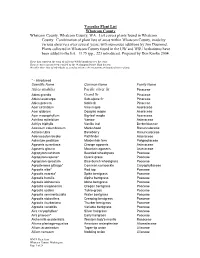

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA. List covers plants found in Whatcom County. Combination of plant lists of areas within Whatcom County, made by various observers over several years, with numerous additions by Jim Duemmel. Plants collected in Whatcom County found in the UW and WSU herbariums have been added to the list. 1175 spp., 223 introduced. Prepared by Don Knoke 2004. These lists represent the work of different WNPS members over the years. Their accuracy has not been verified by the Washington Native Plant Society. We offer these lists to individuals as a tool to enhance the enjoyment and study of native plants. * - Introduced Scientific Name Common Name Family Name Abies amabilis Pacific silver fir Pinaceae Abies grandis Grand fir Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Sub-alpine fir Pinaceae Abies procera Noble fir Pinaceae Acer circinatum Vine maple Aceraceae Acer glabrum Douglas maple Aceraceae Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf maple Aceraceae Achillea millefolium Yarrow Asteraceae Achlys triphylla Vanilla leaf Berberidaceae Aconitum columbianum Monkshood Ranunculaceae Actaea rubra Baneberry Ranunculaceae Adenocaulon bicolor Pathfinder Asteraceae Adiantum pedatum Maidenhair fern Polypodiaceae Agoseris aurantiaca Orange agoseris Asteraceae Agoseris glauca Mountain agoseris Asteraceae Agropyron caninum Bearded wheatgrass Poaceae Agropyron repens* Quack grass Poaceae Agropyron spicatum Blue-bunch wheatgrass Poaceae Agrostemma githago* Common corncockle Caryophyllaceae Agrostis alba* Red top Poaceae Agrostis exarata* -

Washington Flora Checklist a Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium

Washington Flora Checklist A checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium The Washington Flora Checklist aims to be a complete list of the native and naturalized vascular plants of Washington State, with current classifications, nomenclature and synonymy. The checklist currently contains 3,929 terminal taxa (species, subspecies, and varieties). Taxa included in the checklist: * Native taxa whether extant, extirpated, or extinct. * Exotic taxa that are naturalized, escaped from cultivation, or persisting wild. * Waifs (e.g., ballast plants, escaped crop plants) and other scarcely collected exotics. * Interspecific hybrids that are frequent or self-maintaining. * Some unnamed taxa in the process of being described. Family classifications follow APG IV for angiosperms, PPG I (J. Syst. Evol. 54:563?603. 2016.) for pteridophytes, and Christenhusz et al. (Phytotaxa 19:55?70. 2011.) for gymnosperms, with a few exceptions. Nomenclature and synonymy at the rank of genus and below follows the 2nd Edition of the Flora of the Pacific Northwest except where superceded by new information. Accepted names are indicated with blue font; synonyms with black font. Native species and infraspecies are marked with boldface font. Please note: This is a working checklist, continuously updated. Use it at your discretion. Created from the Washington Flora Checklist Database on September 17th, 2018 at 9:47pm PST. Available online at http://biology.burke.washington.edu/waflora/checklist.php Comments and questions should be addressed to the checklist administrators: David Giblin ([email protected]) Peter Zika ([email protected]) Suggested citation: Weinmann, F., P.F. Zika, D.E. Giblin, B. -

PTERIDOLOGIST 2012 Contents: Volume 5 Part 5, 2012 Scale Insect Pests of Ornamental Ferns Grown Indoors in Britain

PTERIDOLOGIST 2012 Contents: Volume 5 Part 5, 2012 Scale insect pests of ornamental ferns grown indoors in Britain. Dr. Chris Malumphy 306 Familiar Ferns in a Far Flung Paradise. Georgina A.Snelling 313 Book Review: A Field Guide to the Flora of South Georgia. Graham Ackers 318 Survivors. Neill Timm 320 The Dead of Winter? Keeping Tree Ferns Alive in the U.K. Mike Fletcher 322 Samuel Salt. Snapshots of a Victorian Fern Enthusiast. Nigel Gilligan 327 New faces at the Spore Exchange. Brian and Sue Dockerill 331 Footnote: Musotima nitidalis - a fern-feeding moth new to Britain. Chris Malumphy 331 Leaf-mining moths in Britain. Roger Golding 332 Book Review: Ferns of Southern Africa. A Comprehensive Guide. Tim Pyner 335 Stem dichotomy in Cyathea australis. Peter Bostock and Laurence Knight 336 Mrs Puffer’s Marsh Fern. Graham Ackers 340 Young Ponga Frond. Guenther K. Machol 343 Polypodium Species and Hybrids in the Yorkshire Dales. Ken Trewren 344 A Challenge to all Fern Lovers! Jennifer M. Ide 348 Lycopodiums: Trials in Pot Cultivation. Jerry Copeland 349 Book Review: Fern Fever. Alec Greening 359 Fern hunting in China, 2010. Yvonne Golding 360 Stamp collecting. Martin Rickard 365 Dreaming of Ferns. Tim Penrose 366 Variation in Asplenium scolopendrium. John Fielding 368 The Case for Filmy Ferns. Kylie Stocks 370 Polystichum setiferum ‘Cristato-gracile’. Julian Reed 372 Why is Chris Page’s “Ferns” So Expensive? Graham Ackers 374 A Magificent Housefern - Goniophlebium Subauriculatum. Bryan Smith 377 A Bolton Collection. Jack Bouckley 378 360 Snails, Slugs, Grasshoppers and Caterpillars. Steve Lamont 379 Sphenomeris chinensis. -

Recent Taxonomic Changes for Oregon Ferns and Fern Allies

Literature Cited Greenland. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. Ayensu E.S. and R.A. DeFilipps. 1978. Endangered and Peck, M.E. 1954. Notes on certain Oregon plants with descrip- Threatened Plants of the United States. Smithsonian Institu- tion of new varieties. Leaflets of Western Botany 7(7): 177-200. tion and World Wildlife Fund, Washington, D.C. 1978. 403 pp. Peck, M.E. 1961. A Manual of the Higher Plants of Oregon. Binford and Mort, Portland, Oregon. 936 pp. Barneby, R.L. 1964. Atlas of the North American Astragalus. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden, Vol. 13, Part I- Schaack, C.O. 1983. A monographic revision of the genera II. The New York Botanical Garden, New York. Synthyris and Besseya (Scrophulariaceae). Ph.D. diss., Univ. Montana, Missoula. Chambers, K.L. 1989. Taxonomic relationships of Allocarya corallicarpa (Boraginaceae). Madrono 36(4): 280-282. Siddall, J.L., K.1. Chambers, and D.H. Wagner. 1979. Rare, threatened and endangered vascular plants in Oregon — an Garcon, J.G. 1986. Report on the status of Arenaria frank/inn interim report. Oregon Natural Area Preserves Advisory Corn- Dougl. ex Hook var. thornpsonii Peck. Unpubl. rept., mittee, Division of State Lands. 109 pp. Washington Natural Heritage Program, Olympia. 24 pp. Strother, J.L. and W.J. Ferlatte. 1988. Review of Erigeron eatonii Kartesz, J.T. and R. Kartesz. 1980. A Synonymized Checklist and allied taxa (Compositae: Astereae). Madrono 35(2): 77-91. of the Vascular Flora of the United States, Canada and Recent Taxonomic Changes for Oregon Ferns and Fern Allies By EDWARD R. -

Falkland Islands Species List

Falkland Islands Species List Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 BIRDS* 2 DUCKS, GEESE, & WATERFOWL Anseriformes - Anatidae 3 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus 4 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba 5 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta 6 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida 7 Ruddy-headed Goose Chloephaga rubidiceps 8 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus 9 Falkland Steamer-Duck Tachyeres brachypterus 10 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides 11 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix 12 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 13 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera 14 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica 15 Silver Teal Anas versicolor 16 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris 17 GREBES Podicipediformes - Podicipedidae 18 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland 19 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis 20 PENGUINS Sphenisciformes - Spheniscidae 21 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus 22 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua Cheesemans' Ecology Safaris Species List Updated: April 2017 Page 1 of 11 Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 23 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus 24 Macaroni Penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus 25 Southern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome 26 ALBATROSSES Procellariiformes - Diomedeidae 27 Gray-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma 28 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris 29 Royal Albatross (Southern) Diomedea epomophora epomophora 30 Royal Albatross (Northern) Diomedea epomophora sanfordi 31 Wandering Albatross (Snowy) Diomedea exulans exulans 32 Wandering -

Two Beringian Origins for the Allotetraploid Fern Polystichum Braunii (Dryopteridaceae)

Systematic Botany (2017), 42(1): pp. 6–16 © Copyright 2017 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists DOI 10.1600/036364417X694557 Date of publication March 1, 2017 Two Beringian Origins for the Allotetraploid Fern Polystichum braunii (Dryopteridaceae) Stacy A. Jorgensen1 and David S. Barrington2 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, PO 210088, Tucson, Arizona 85719, U. S. A. 2Pringle Herbarium, Plant Biology Department, The University of Vermont, 27 Colchester Drive, Burlington, Vermont 05405, U. S. A. Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Communicating Editor: Marcia Waterway Abstract—Although some polyploids in the genus Polystichum are well studied and have well-resolved evolutionary histories, the origin of the circumboreally distributed allotetraploid Polystichum braunii remains obscure. We use the chloroplast markers rbcL, rps4-trnS, and trnL-F as well as the nuclear markers pgiC and gapCp to demonstrate that P. braunii is a single allotetraploid with a minimum of two origins. The two variants isolated from the nucleus resolve with divergent clades, one eastern Asian and one North American. However, they do not have near allies among morphologically appropriate taxa in our sample; the North American progenitor appears to be extinct. A divergence-time analysis based on the cpDNA markers yielded evidence of an older time of origin for P. br au nii than for an array of well-known allotetraploids in the eupolypod ferns. Niche modeling in the light of geological and paleontological evidence leads to the conclusion that the two origins were in Beringia. Since P. braunii is genetically undifferentiated but widely distributed, we argue that it has expanded to its circumboreal range in the recent past, though it has a relatively ancient origin. -

Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Vascular Plants in Oregon

RARE, THREATENED AND ENDANGERED VASCULAR PLANTS IN OREGON --AN INTERIM REPORT i •< . * •• Jean L. Siddall Kenton . Chambers David H. Wagner L Vorobik. 779 OREGON NATURAL AREA PRESERVES ADVISORY COMMITTEE to the State Land Board Salem, October, 1979 Natural Area Preserves Advisory Committee to the State Land Board Victor Atiyeh Norma Paulus Clay Myers Governor Secretary of State State Treasurer Members Robert E. Frenkel (Chairman), Corvallis Bruce Nolf (Vice Chairman), Bend Charles Collins, Roseburg Richard Forbes, Portland Jefferson Gonor, Newport Jean L. Siddall, Lake Oswego David H. Wagner, Eugene Ex-Officio Members Judith Hvam Will iam S. Phelps Department of Fish and Wildlife State Forestry Department Peter Bond J. Morris Johnson State Parks and Recreation Division State System of Higher Education Copies available from: Division of State Lands, 1445 State Street, Salem,Oregon 97310. Cover: Darlingtonia californica. Illustration by Linda Vorobik, Eugene, Oregon. RARE, THREATENED AND ENDANGERED VASCULAR PLANTS IN OREGON - an Interim Report by Jean L. Siddall Chairman Oregon Rare and Endangered Plant Species Taskforce Lake Oswego, Oregon Kenton L. Chambers Professor of Botany and Curator of Herbarium Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon David H. Wagner Director and Curator of Herbarium University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon Oregon Natural Area Preserves Advisory Committee Oregon State Land Board Division of State Lands Salem, Oregon October 1979 F O R E W O R D This report on rare, threatened and endangered vascular plants in Oregon is a basic document in the process of inventorying the state's natural areas * Prerequisite to the orderly establishment of natural preserves for research and conservation in Oregon are (1) a classification of the ecological types, and (2) a listing of the special organisms, which should be represented in a comprehensive system of designated natural areas. -

Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Institute for Natural Resources Publications Institute for Natural Resources - Portland 10-2010 Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon James S. Kagan Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Sue Vrilakas Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, [email protected] Eleanor P. Gaines Portland State University Cliff Alton Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Lindsey Koepke Oregon Biodiversity Information Center See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/naturalresources_pub Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2010. Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon. Institute for Natural Resources, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. 105 pp. This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute for Natural Resources Publications by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors James S. Kagan, Sue Vrilakas, Eleanor P. Gaines, Cliff Alton, Lindsey Koepke, John A. Christy, and Erin Doyle This book is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/naturalresources_pub/24 RARE, THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES OF OREGON OREGON BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION CENTER October 2010 Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Institute for Natural Resources Portland State University PO Box 751, Mail Stop: INR Portland, OR 97207-0751 (503) 725-9950 http://orbic.pdx.edu With assistance from: Native Plant Society of Oregon The Nature Conservancy Oregon Department of Agriculture Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Oregon Department of State Lands Oregon Natural Heritage Advisory Council U.S. -

Rare, Threatened, and Endangered

Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Institute for Natural Resources Portland State University P.O. Box 751, Mail Stop: INR Portland, OR 97207-0751 (503) 725-9950 http://inr.oregonstate.edu/orbic With assistance from: U.S. Forest Service Bureau of Land Management U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service NatureServe OregonFlora at Oregon State University The Nature Conservancy Oregon Parks and Recreation Department Oregon Department of State Lands Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Oregon Department of Agriculture Native Plant Society of Oregon Compiled and published by the following staff at the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center: Jimmy Kagan, Director/Ecologist Sue Vrilakas, Botanist/Data Manager Eleanor Gaines, Zoologist Lindsey Wise, Botanist/Data Manager Michael Russell, Botanist/Ecologist Cayla Sigrah, GIS and Database Support Specialist Cover Photo: Charadrius nivosus (Snowy plover chick and adult). Photo by Cathy Tronquet. ORBIC Street Address: Portland State University, Science and Education Center, 2112 SW Fifth Ave., Suite 140, Portland, Oregon, 97201 ORBIC Mailing Address: Portland State University, Mail Stop: INR, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 Bibliographic reference to this publication should read: Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2019. Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon. Institute for Natural Resources, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. 133 pp. CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................