Merritt Fernald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

WO 2016/061206 Al 21 April 2016 (21.04.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/061206 Al 21 April 2016 (21.04.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: BAUER, Christopher; PIONEER HI-BRED IN C12N 15/82 (2006.01) A01N 65/00 (2009.01) TERNATIONAL, INC., 7100 N.W. 62nd Avenue, John C07K 14/415 (2006.01) ston, Iowa 5013 1-1014 (US). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/US2015/055502 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (22) Date: International Filing BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, 14 October 2015 (14.10.201 5) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (25) Filing Language: English HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, (26) Publication Language: English MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (30) Priority Data: PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 62/064,810 16 October 20 14 ( 16.10.20 14) US SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (71) Applicants: PIONEER HI-BRED INTERNATIONAL, INC. [US/US]; 7100 N.W. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Typifications and Synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae) from Chile and Argentina

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeys 65: 91–105 (2016)Typifications and synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae)... 91 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.65.8620 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://phytokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Typifications and synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae) from Chile and Argentina Rita E. Morero1,2, David S. Barrington3, Monique A. McHenry3, João P. S. Condack4, Gloria E. Barboza1,2 1 Departamento de Farmacia, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, (UNC), Av. Medina Allende y Haya de la Torre. Ciudad Universitaria, Córdoba. Argentina 2 Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal (IMBIV-CONICET), Casilla de Correo 495, 5000 Córdoba 3 University of Vermont, Pringle Herbarium, Torrey Hall, 27 Colchester Ave, Burlington, VT 05405 4 Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista s.n., São Cristóvão, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 20940-040 Corresponding authors: Rita E. Morero ([email protected]); Gloria E. Barboza ([email protected]) Academic editor: Blanca Leon | Received 24 March 2016 | Accepted 6 June 2016 | Published 30 June 2016 Citation: Morero RE, Barrington DS, McHenry MA, Condack JPS, Barboza GE (2016) Typifications and synonymy in Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae) from Chile and Argentina. PhytoKeys 65: 91–105. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.65.8620 Abstract Polystichum Roth is one of the largest and most taxonomically challenging fern genera. South American species have a rich and complex nomenclatural history; many of the early names are inadequately typified. Based on extensive examination of original type material, we designate eleven lectotypes (including As- pidium mohrioides, A. montevidense f. imbricata, A. montevidense f. squamulosa, A. -

1 Sex Ratio and Spatial Distribution of Male and Female Antennaria Dioica

Sex ratio and spatial distribution of male and female Antennaria dioica (Asteraceae) plants Sandra Varga* and Minna-Maarit Kytöviita Department of Biological and Environmental Science, University of Jyväskylä, P.O. Box 35, FIN- 40014 Jyväskylä, Finland E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] (S. Varga), minna- [email protected] (M.-M. Kytöviita) *Author for correspondence: Sandra Varga Department of Biological and Environmental Science University of Jyväskylä FIN-40014 Jyväskylä Finland Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Phone: +358 14 260 2304 Fax: +358 14 260 2321 1 Abstract Sex ratio, sex spatial distribution and sexual dimorphism in reproduction and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation were investigated in the dioecious clonal plant Antennaria dioica (Asteraceae). Plants were monitored for five consecutive years in six study plots in Oulanka, northern Finland. Sex ratio, spatial distribution of sexes, flowering frequency, number of floral shoots and the number and weight of inflorescences were recorded. In addition, intensity of mycorrhizal fungi in the roots was assessed. Both sexes flowered each year with a similar frequency, but the overall genet sex ratio was strongly female-biased. The bivariate Ripley’s analysis of the sex distribution showed that within most plots sexes were randomly distributed except for one plot. Sexual dimorphism was expressed as larger floral and inflorescence production and heavier inflorescences in males. In addition, the roots of both sexes were colonised to a similar extent by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. The female sex-biased flowering ratios reported are not consistent among years and cannot be explained in terms of spatial segregation of the sexes or sex lability. -

Fdn22 Northern Dry-Bedrock Pine (Oak) Woodland *Spinulose Shield Fern Or Glandular Wood Fern ( Dryopteris Carthusiana Or D

FIRE-DEPENDENT FOREST/WOODLAND SYSTEM FDn22 Northern Floristic Region Northern Dry-Bedrock Pine (Oak) Woodland Dry pine or oak woodlands on shallow, excessively drained, loamy soils on bedrock ridges and hillsides or on rock ledges and terraces adjacent to rivers. Crown and surface fires were common historically. Vegetation Structure & Composition Description is based on summary of vegetation data from 47 plots (relevés). Ground-layer cover of forbs and grami- noids typically ranges from 25-75%. The most common vascular plants are Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), large-leaved aster (Aster macrophyllus), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), and bracken (Pteridium aqui- linum). Lichen- and moss-covered bedrock and boulders typically make up at least 25% of the ground layer. Shrub layer is typically dominated by deciduous species, usually with patchy to interrupted cover (25-75%). Lowbush blue- berry (Vaccinium angustifolium), juneberries (Amelanchier spp.), red maple saplings, and bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera) are the most common species in the shrub layer. Subcanopy is usually absent, but when present, red maple and paper birch are frequent components. Canopy is composed of conifers, hardwoods, or conifers mixed with hardwoods, and is usually patchy (25-50% cover), with openings in areas of exposed bedrock or boulders. Red pine and white pine are dominant on many sites. On other sites, jack pine or northern pin oak are dominant. In mixed forests, conifers often form a supercanopy above hardwood species. Paper birch is often present in the hardwood canopy. Landscape Setting & Soils Glacially scoured bedrock—Common. Landscape is hummocky to rugged. Parent material is non-calcareous drift, usually less than 20in (50cm) deep over bedrock. -

Vascular Plant Inventory of Mount Rainier National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Vascular Plant Inventory of Mount Rainier National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2010/347 ON THE COVER Mount Rainier and meadow courtesy of 2007 Mount Rainier National Park Vegetation Crew Vascular Plant Inventory of Mount Rainier National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2010/347 Regina M. Rochefort North Cascades National Park Service Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, Washington 98284 June 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received informal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

Chapter 5: Vegetation of Sphagnum-Dominated Peatlands

CHAPTER 5: VEGETATION OF SPHAGNUM-DOMINATED PEATLANDS As discussed in the previous chapters, peatland ecosystems have unique chemical, physical, and biological properties that have given rise to equally unique plant communities. As indicated in Chapter 1, extensive literature exists on the classification, description, and ecology of peatland ecosystems in Europe, the northeastern United States, Canada, and the Rocky Mountains. In addition to the references cited in Chapter 1, there is some other relatively recent literature on peatlands (Verhoeven 1992; Heinselman 1963, 1970; Chadde et al., 1998). Except for efforts on the classification and ecology of peatlands in British Columbia by the National Wetlands Working Group (1988), the Burns Bog Ecosystem Review (Hebda et al. 2000), and the preliminary classification of native, low elevation, freshwater vegetation in western Washington (Kunze 1994), scant information exists on peatlands within the more temperate lowland or maritime climates of the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia). 5.1 Introduction There are a number of classification schemes and many different peatland types, but most use vegetation in addition to hydrology, chemistry and topological characteristics to differentiate among peatlands. The subject of this report are acidic peatlands that support acidophilic (acid-loving) and xerophytic vegetation, such as Sphagnum mosses and ericaceous shrubs. Ecosystems in Washington state appear to represent a mosaic of vegetation communities at various stages of succession and are herein referred to collectively as Sphagnum-dominated peatlands. Although there has been some recognition of the unique ecological and societal values of peatlands in Washington, a statewide classification scheme has not been formally adopted or widely recognized in the scientific community. -

Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado

Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado 2005 Prepared by Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University Fort Collins CO 80523 Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado 2005 Prepared by Peggy Lyon and Julia Hanson Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University Fort Collins CO 80523 December 2005 Cover: Imperiled (G1 and G2) plants of the San Juan Public Lands, top left to bottom right: Lesquerella pruinosa, Draba graminea, Cryptantha gypsophila, Machaeranthera coloradoensis, Astragalus naturitensis, Physaria pulvinata, Ipomopsis polyantha, Townsendia glabella, Townsendia rothrockii. Executive Summary This survey was a continuation of several years of rare plant survey on San Juan Public Lands. Funding for the project was provided by San Juan National Forest and the San Juan Resource Area of the Bureau of Land Management. Previous rare plant surveys on San Juan Public Lands by CNHP were conducted in conjunction with county wide surveys of La Plata, Archuleta, San Juan and San Miguel counties, with partial funding from Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO); and in 2004, public lands only in Dolores and Montezuma counties, funded entirely by the San Juan Public Lands. Funding for 2005 was again provided by San Juan Public Lands. The primary emphases for field work in 2005 were: 1. revisit and update information on rare plant occurrences of agency sensitive species in the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) database that were last observed prior to 2000, in order to have the most current information available for informing the revision of the Resource Management Plan for the San Juan Public Lands (BLM and San Juan National Forest); 2. -

Prairie Restoration Technical Guides

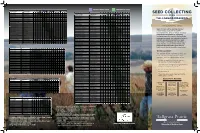

Optimal Collection Period Seed Ripening Period EARLY SEASON NATIVE FORBS May June July August September EARLY SEASON NATIVE FORBS May June July August SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 Caltha palustris Marsh marigold LATE SEASON NATIVE FORBS August September October November SEED COLLECTING Prairie smoke SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 FROM Antennaria neglecta Pussytoes Stachys palustris Woundwort Castilleja coccinea Indian paintbrush Vicia americana Vetch False dandelion Rudbeckia hirta Black-eyed Susan TALLGRASS PRAIRIES Saxifraga pensylvanica Swamp saxifrage Lobelia spicata Spiked lobelia Senecio aureus Golden ragwort Iris shrevei Sisyrinchium campestre Blue-eyed grass Hypoxis hirsuta Yellow star grass Rosa carolina Pasture rose Content by Greg Houseal Pedicularis canadensis Lousewort Oxypolis rigidior Cowbane PRAIRIE RESTORATION SERIES V Prairie violet Vernonia fasciculata Ironweed Cardamine bulbosa Spring cress Veronicastrum virginicum Culver's root Allium canadense Wild garlic Heliopsis helianthoides Seed of many native species are now Lithospermum canescens Hoary puccoon L Narrow-leaved loosestrife commercially1 available for prairie Phlox maculata Marsh phlox Lythrum alatum Winged loosestrife Phlox pilosa Prairie phlox reconstructions, large or small. Yet many Ceanothus americana New Jersey tea Anemone canadensis Canada anemone Eupatorium maculatum Spotted Joe Pye people have an interest in collecting Prunella vulgaris var.