Chapter One: the Soybean, It's History, and It's Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

54 Soy-Milk Waste with Soybean Meal Dietary Substitution

Jurnal Peternakan Indonesia, Juni 2017 Vol. 19 (2): 54-59 ISSN 1907-1760 E-ISSN 2460-3716 Soy-Milk Waste with Soybean Meal Dietary Substitution: Effects on Growth Performance and Meat Quality of Broiler Chickens Penggantian Bungkil Kedelai dengan Ampas Susu Kedelai dalam Pakan: Pengaruhnya pada Kinerja Pertumbuhan dan Kualitas Daging Ayam Broiler N. D. Dono*, E. Indarto, and Soeparno1 1Faculty of Animal Science, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 55281 E-mail: [email protected] (Diterima: 23 Februari 2017; Disetujui: 12 April 2017) ABSTRACT Sixty male broiler chickens was used to investigate the effects of dietary soybean meal (SBM) with soy-milk waste (SMW) substitution using growth performance, protein-energy efficiency ratio, and physical meat quality as response criteria. The birds were given control diet (SMW-0), or a control diets with 5% (SMW-1), 10% (SMW-2), and 15% (SMW-3) soy-milk waste substitutions. Each treatment was replicate 3 times, with 5 birds per replication. The obtained data were subjected to Oneway arrangement of A129A, and continued suEsequently with Duncan‘s new 0ultiple Range Test. Results showed that substituting SBM with SMW did not influence protein and energy consumption, as well as feed consumption and energy efficiency ratio. However, dietary substitution with 10% SMW improved (P<0.05) protein efficiency ratio, body weight gain, and slaughter weight, resulting in lower (P<0.05) feed conversion ratio. The meat pH, water holding capacity, cooking loss, and tenderness values did not influence by 5-15% SMW substitution. Keywords: broiler chickens, growth performance, physical meat quality, soybean meal substitution, soy- milk waste ABSTRAK Enam puluh ekor ayam broiler jantan digunakan untuk mengetahui pengaruh penggantian tepung bungkil kedelai (SBM) dengan ampas susu kedelai (SMW) dengan menggunakan kinerja pertumbuhan, rasio efisiensi protein-energi, serta kualitas fisik daging sebagai respon kriteria yang diamati. -

(Okara) As Sustainable Ingredients for Nile Tilapia (O

animals Article Processed By-Products from Soy Beverage (Okara) as Sustainable Ingredients for Nile Tilapia (O. niloticus) Juveniles: Effects on Nutrient Utilization and Muscle Quality Glenise B. Voss 1,2, Vera Sousa 1,3, Paulo Rema 1,4, Manuela. E. Pintado 2 and Luísa M. P. Valente 1,3,* 1 CIIMAR/CIMAR—Centro Interdisciplinar de Investigação Marinha e Ambiental, Universidade do Porto, Terminal de Cruzeiros do Porto de Leixões, Avenida General Nórton de Matos, S/N, 4450-208 Matosinhos, Portugal; [email protected] (G.B.V.); [email protected] (V.S.); [email protected] (P.R.) 2 CBQF—Laboratório Associado, Centro de Biotecnologia e Química Fina, Escola Superior de Biotecnologia, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Rua Diogo Botelho 1327, 4169-005 Porto, Portugal; [email protected] 3 ICBAS—Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas de Abel Salazar, Universidade do Porto, Rua de Jorge Viterbo Ferreira, 228, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 4 UTAD—Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Quinta de Prados, 5001-801 Vila Real, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-223-401-825; Fax: +351-223-390-608 Simple Summary: The consumption of soy products increases worldwide and generates large amounts of by-products, which are often discarded. Okara is a soybean by-product with high nutritional value. This work evidenced the great potential of okara meal, after appropriate technological processing, to be used as feed ingredient in Nile tilapia diets. It was clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of Citation: Voss, G.B.; Sousa, V.; Rema, the autoclave and the use of proteases from C. cardunculus without fermentation to increase okara P.; Pintado, M..E.; Valente, L.M.P. -

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans Session 2 Assessment Background Information Tips Goals Vegetables, Fruit, Assessment of Whole Grains, Current Eating Habits and Beans On an average DAY, how many servings of these Could be Needs to foods do you eat or drink? Desirable improved be improved 1. Greens and non-starchy vegetables like collard, 4+ 2-3 0-1 mustard, or turnip greens, salads made with dark- green leafy lettuces, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, carrots, okra, zucchini, squash, turnips, onions, cabbage, spinach, mushrooms, bell peppers, or tomatoes (including tomato sauce) 2. Fresh, canned (in own juice or light syrup), or 3+ 1-2 0 frozen fruit or 100% fruit juice (½ cup of juice equals a serving) 3a. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Never Some Most of with white flour of the time the time 3b. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Most Some Never with whole wheat flour of the time of the time In an average WEEK, how many servings of these foods do you eat? 4. Starchy vegetables like acorn squash, butternut 4-7 2-3 0-1 squash, beets, green peas, sweet potatoes, or yams (do not include white potatoes) 5. White potatoes, including French fries and 1 or less 2-3 4+ potato chips 6. Beans or peas like pinto beans, kidney beans, 3+ 1-2 0 black beans, lentils, butter or lima beans, or black-eyed peas Continued on next page Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, and Beans 19 Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, Assessment of and Beans Current Eating Habits In an average WEEK, how often or how many servings of these foods do you eat? 7a. -

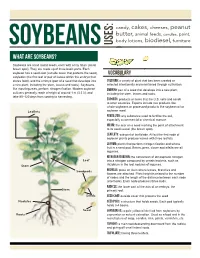

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Distribution of Isoflavones and Coumestrol in Fermented Miso and Edible Soybean Sprouts Gwendolyn Kay Buseman Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-1996 Distribution of isoflavones and coumestrol in fermented miso and edible soybean sprouts Gwendolyn Kay Buseman Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Buseman, Gwendolyn Kay, "Distribution of isoflavones and coumestrol in fermented miso and edible soybean sprouts" (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18032. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18032 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Distribution of isoflavones and coumestrol in fermented miso and edible soybean sprouts by Gwendolyn Kay Buseman A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department Food Science and Human Nutrition Major: Food Science and Technology Major Professor: Patricia A. Murphy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Gwendolyn Kay Buseman has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES -

Bean and Tomato Soup

Bean and Tomato Soup Schoharie County Apple Filled Squash Schoharie173 County South Grand StApple Filled Squash 173 SouthCobleskill, Grand St NY 12043 Cobleskill, NY 12043518.234.4303 Ingredients:Ingredients Instructions 518.234.4303518.296.8310 Ingredients Instructions 518.296.8310Fax: 518.234.4305 1 Tablespoon2 acorn, buttercup vegetable or oil 1. Preheat oven to 350° F. Fax: [email protected] 2 acorn,1 mediumbutternut buttercup onion, squash or chopped 1. Preheat oven to 350° F. [email protected] butternut squash 2 garlic cloves, minced 2. Cut squash in half and 2 large apples, peeled,2. Cut squashremove in half seeds. and Otsego County 2 (14½-ounce) cans white kidney beans, Otsego County123 Lake St 2 large cored,apples, chopped peeled, remove seeds. Cooperstown,123 Lake St NY 13326 cored, drained chopped and rinsed 3. Place squash halves in Cooperstown, NY 13326607.547.2536 1 (13¾-ounce)2½ Tablespoons can low brown3. sodium Place chicken squashbaking broth halvesdish cut in side down in 607.547.2536Fax: 607.547.5180 2½ Tablespoons1 cupsugar water brown baking dishabout cut 1 inchside ofdown water. in Fax: [email protected] sugar about 1 inch of water. ¼ teaspoon black pepper [email protected] 2½ Tablespoons melted 4. Bake for 20 minutes. Oneonta Outreach 2½ Tablespoons½ teaspoonbutter Italian melted seasoning, 4. Bake crushed for 20 minutes. Oneonta Outreach31 Maple St butter1 (14½-ounce) can diced tomatoes5. While squash is cooking, mix 31 Maple St Oneonta, NY 13820 5. While squash is cooking, mix Oneonta, NY 13820 1 (10-ounce)½ teaspoon package cinnamon* frozen spinach,chopped thawed apple with other 607.433.2521 ½ teaspoon cinnamon* choppedingredients. -

Directory of Us Bean Suppliers · Quality Grown in the Usa

US DRY DIRECTORY OF US BEAN SUPPLIERS · QUALITY GROWN IN THE USA BEANENGLISH SUPPLIERS DIRECTORY DRY BEANS FROM THE USA edn ll R ryn ma ber avyn eyn S an N idn inkn Cr K P ed R rk a D hernn yen ort cke dneyn zon N Bla Ki ban man at d ar Li e Re G ge r t ar G L h ig L ton Pin Liman ckn y Bla iman n ab y L dzuki B ab A B n e re G U.S. DRY BEANS www.usdrybeans.com International Year of the Pulse 2016 · www.iyop.net 01 n Pink Adzuki Large Lima Pink Garbanzo Dark Red Kidney Great Northern an Lim ge ar L Small Red Navy Black Baby Lima Blackeye Light Red Kidney in dzuk A Green Baby Lima Pinto Cranberry TABLE OF CONTENTS About the US Dry Bean Council 2 US Dry Bean Council Overseas Representatives 3 USDBC Members and Producers Organisations4 Major US Dry Bean Classes 6 Dry Bean Production Across the US 8 Companies by Bean Class 10 Alphabetical Listing Of US Dry Bean Suppliers 14 Nutritional Value 34 About the US Dry Bean Industry 36 USDBC Staff 37 02 ABOUT THE US DRY BEAN COUNCIL (USDBC) The USDBC is a trade association comprised of leaders in the bean industry with the common goal of educating US consumers about the benefits of beans. The USDBC gives a voice to the bean industry and provides information to consumers, health professionals, educators USDBC USA and the media about the good taste, nutritional value and Rebecca Bratter, Executive Director versatility of beans. -

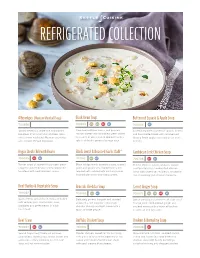

KC Refrigerated Product List 10.1.19.Indd

Created 3.11.09 One Color White REFRIGERATEDWhite: 0C 0M 0Y 0K COLLECTION Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Black Bean Soup Butternut Squash & Apple Soup 700856 700820 VN VG DF GF 700056 GF Savory meatballs, white rice and vibrant Slow-cooked black beans, red peppers, A blend of puréed butternut squash, onions tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken stock roasted sweet corn and diced green chilies and handcrafted stock with caramelized infused with traditional Mexican aromatics in a purée of vine-ripened tomatoes with a Granny Smith apples and a pinch of fresh and a touch of fresh lime juice. splash of fresh-squeezed orange juice. nutmeg. Angus Steak Chili with Beans Black Lentil & Roasted Garlic Dahl* Caribbean Jerk Chicken Soup 700095 DF GF 701762 VG GF 700708 DF GF Tender strips of seared Angus beef, green Black beluga lentils, sautéed onions, roasted Tender chicken, sweet potatoes, carrots peppers and red beans in slow-simmered garlic and ginger slow-simmered in a rich and tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken tomatoes with Southwestern spices. tomato broth, infused with warming spices, stock with white rice, red beans, traditional finished with butter and heavy cream. jerk seasoning and a hint of molasses. Beef Barley & Vegetable Soup Broccoli Cheddar Soup Carrot Ginger Soup 700023 700063 VG GF 700071 VN VG DF GF Seared strips of lean beef and pearl barley Delicately puréed broccoli and sautéed Sweet carrots puréed with fresh-squeezed with red peppers, mushrooms, peas, onions in a rich blend of extra sharp orange juice, hand-peeled ginger and tomatoes and green beans in a rich cheddar cheese and light cream with a sautéed onions with a touch of toasted beef stock. -

Blackeye Bean Production in California

PRODUCTION IN CALIFORNIA UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 21518 For information about ordering this publication, contact Communication Services The technical editors are Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Anthony E. Hall, University of California 6701 San Pablo Avenue Crop Ecologist, UC Riverside, Oakland, California 94608-1239 and Carol A. Frate, UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Tulare County. Telephone (510) 642-2431 within California (800) 994-8849 In addition to the technical editors, other contributing authors are FAX (510) 643-5470 e-mail inquiries to [email protected] David Billings, President, Marketing Cooperative, Ventura; Publication 21518 David W. Cudney Extension Weed Scientist, UC Riverside; Printed in the United States of America. Donald C. Erwin, Plant Pathologist, UC Riverside; ©1996 by the Regents of the University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Peter B. Goodell, Regional IPM Advisor, Kearney Agricultural Center, Parlier; All rights reserved Dard Hunter, No part of this publication may be reproduced, Bean Dealer, San Francisco; stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in Jerry Munson, any form or by any means, electronic, mechan ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, Manager, California Dry Bean Advisory Board; without the written permission of the publish Phillip P. Osterli, er and the authors. UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Stanislaus County; and Philip A. Roberts, The University of California, in accordance Nematologist, UC Riverside. with applicable Federal and State law and University policy, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, The manuscript was reviewed by sex, disability, age, medical condition (cancer- Jim Andreas, related), ancestry, marital status, citizenship, Farmer, Delano; sexual orientation, or status as a Vietnam-era Don Cameron, veteran or special disabled veteran. -

Crediting Legumes in the NSLP and SBP

Crediting Legumes in the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program This guidance applies to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) meal patterns for grades K-12 and preschoolers (ages 1-4) in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), School Breakfast Program (SBP), Seamless Summer Option (SSO) of the NSLP, and Afterschool Snack Program (ASP) of the NSLP. For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods for grades K-12, visit the Connecticut State Department of Education’s (CSDE) Meal Patterns for Grades K-12 in School Nutrition Programs and Crediting Foods in School Nutrition Programs webpages. For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods for preschoolers, visit the CSDE’s Meal Patterns for Preschoolers in School Nutrition Programs webpage. Legumes include cooked dry beans and peas, such as black beans, black-eyed peas (mature, dry), edamame (soybeans), garbanzo beans (chickpeas), kidney beans, lentils, navy beans, soybeans, split peas, and white beans. Legumes may credit as either the meat/meat alternates component or the vegetables component, but one serving cannot credit as both components in the same meal or snack. Menu planners must determine in advance how to credit legumes in a meal. A ¼-cup serving of legumes credits as 1 ounce of the meat/meat alternates component or ¼ cup of the vegetables component. Legumes may credit as either component in different meals. For example, lentils may credit as the vegetables component at one lunch, and as the meat/meat alternates component at another lunch. If the meal includes two servings of legumes, the menu planner may choose to credit one serving as the vegetables component and one serving as the meat/meat alternates component. -

Okara: a Possible High Protein Feedstuff for Organic Pig Diets

Animal Industry Report Animal Industry Report AS 650 ASL R1965 2004 Okara: A Possible High Protein Feedstuff For Organic Pig Diets J. R. Hermann Iowa State University Mark S. Honeyman Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ans_air Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hermann, J. R. and Honeyman, Mark S. (2004) "Okara: A Possible High Protein Feedstuff For Organic Pig Diets," Animal Industry Report: AS 650, ASL R1965. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31274/ans_air-180814-197 Available at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ans_air/vol650/iss1/124 This Swine is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal Science Research Reports at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Animal Industry Report by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iowa State University Animal Industry Report 2004 Swine Okara: A Possible High Protein Feedstuff For Organic Pig Diets A.S. Leaflet R1965 creating disposal problems (3). Work with okara as an alternative feedstuff is limited (4). We know of no published J.R. Hermann, Research Assistant, studies involving okara as an alternative swine feedstuff. M.S. Honeyman, Professor, Therefore our objective was to determine the effect of Department of Animal Science dietary okara on growth performance of young pigs. Summary and Implications Materials and Methods A potential alternative organic protein source is okara. Animals Okara is the residue left from ground soybeans after Four replicate trials involving a total of 48 pigs extraction of the water portion used to produce soy milk and (average initial body weight of 13.23 kg) were conducted at tofu. -

Report Name:Utilization of Food-Grade Soybeans in Japan

Voluntary Report – Voluntary - Public Distribution Date: March 24, 2021 Report Number: JA2021-0040 Report Name: Utilization of Food-Grade Soybeans in Japan Country: Japan Post: Tokyo Report Category: Oilseeds and Products Prepared By: Daisuke Sasatani Approved By: Mariya Rakhovskaya Report Highlights: This report provides an overview of food-grade soybean use and market trends in Japan. Manufacturing requirements for traditional Japanese foods (e.g. tofu, natto, miso, soy sauce, simmered soybean) largely determine characteristics of domestic and imported food-grade soybean varieties consumed in Japan. Food-Grade Soybeans THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Soybeans (Glycine max) can be classified into two distinct categories based on use: (i) food-grade, primarily used for direct human consumption and (ii) feed-grade, primarily used for crushing and animal feed. In comparison to feed-grade soybeans, food-grade soybeans used in Japan have a higher protein and sugar content, typically lower yield and are not genetically engineered (GE). Japan is a key importer of both feed-grade and food-grade soybeans (2020 Japan Oilseeds Annual). History of food soy in Japan Following introduction of soybeans from China, the legume became a staple of the Japanese diet. By the 12th century, the Japanese widely cultivate soybeans, a key protein source in the traditional largely meat-free Buddhist diet. Soybean products continue to be a fundamental component of the Japanese diet even as Japan’s consumption of animal products has dramatically increased over the past century. During the last 40 years, soy products have steadily represented approximately 10 percent (8.7 grams per day per capita) of the overall daily protein intake in Japan (Figure 1).