Jounal of APFCSC VOL3 Issue1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madan Bhandari Highway

Report on Environmental, Social and Economic Impacts of Madan Bhandari Highway DECEMBER 17, 2019 NEFEJ Lalitpur Executive Summary The report of the eastern section of Madan Bhandari Highway was prepared on the basis of Hetauda-Sindhuli-Gaighat-Basaha-Chatara 371 km field study, discussion with the locals and the opinion of experts and reports. •During 2050's,Udaypur, Sindhuli and MakwanpurVillage Coordination Committee opened track and constructed 3 meters width road in their respective districts with an aim of linking inner Madhesh with their respective headquarters. In the background of the first Madhesh Movement, the road department started work on the concept of alternative roads. Initially, the double lane road was planned for an alternative highway of about 7 meters width. The construction of the four-lane highway under the plan of national pride began after the formation of a new government of the federal Nepal on the backdrop of the 2072 blockade and the Madhesh movement. The Construction of Highway was enunciated without the preparation of an Environmental Impact Assessment Report despite the fact that it required EIA before the implementation of the big physical plan of long-term importance. Only the paper works were done on the study and design of the alternative highway concept. The required reports and construction laws were abolished from the psychology that strong reporting like EIA could be a hindrance to the roads being constructed through sensitive terrain like Chure (Siwalik). • During the widening of the roads, 8 thousand 2 hundred and 55 different trees of community forest of Makwanpur, Sindhuli and Udaypur districtsare cut. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (Muan) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN)

Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (MuAN) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden European Sverige Union "This document has been financed by the Swedish "This publication was produced with the financial support of International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of does not necessarily share the views expressed in this MuAN, NARMIN, ADCCN and UCLG and do not necessarily material. Responsibility for its content rests entirely with the reflect the views of the European Union'; author." Publication Date June 2020 Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal (MuAN) National Association of Rural Municipality in Nepal (NARMIN) Association of District Coordination Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden Sverige European Union Expert Services Dr. Dileep K. Adhikary Editing service for the publication was contributed by; Mr Kalanidhi Devkota, Executive Director, MuAN Mr Bimal Pokheral, Executive Director, NARMIN Mr Krishna Chandra Neupane, Executive Secretary General, ADCCN Layout Designed and Supported by Edgardo Bilsky, UCLG world Dinesh Shrestha, IT Officer, ADCCN Table of Contents Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... -

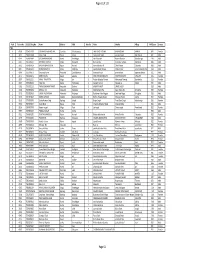

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

![आकाश स िंह राम प्रघट स िंह राकेश स िंह P]G Axfb"/ Af]Xf]/F L;Krg](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4868/p-g-axfb-af-xf-f-l-krg-1494868.webp)

आकाश स िंह राम प्रघट स िंह राकेश स िंह P]G Axfb"/ Af]Xf]/F L;Krg

खुला प्रलतयोलगता配मक परीक्षाको वीकृ त नामावली वबज्ञापन नं. : २०७७/७८/३४ (कर्ाला ी प्रदेश) तह : ३ पदः कलनष्ठ सहायक (गो쥍ड टेटर) सम्륍मललत हुन रोल नं. उ륍मेदवारको नाम उ륍मेदवारको नाम (देवनागरीमा) ललंग थायी म्ि쥍ला थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स बािेको नाम बाबुको नाम चाहेको समूह 1 AAKASH SINGH आकाश स िंह Male ख쥍ु ला Banke Nepalgunj Sub-Metropolitian City राम प्रघट स िंह राके श स िंह 2 AIN BAHADUR BOHARA P]g axfb"/ af]xf]/f Male ख쥍ु ला Jumla Patarasi l;krGb| af]xf]/f ;fk{ nfn af]xf]/f 3 AISHWARYA SHAHI ऐश्वर् य शाही Female ख쥍ु ला Surkhet Gurbhakot असिपाल शाही बृज ब शाही 4 AJAR ALI MIYA अजार अली समर्ााँ Male ख쥍ु ला Dailekh Bhairabi आशादली समर्ााँ मर्ु यदली समर्ााँ 5 ALINA BAIGAR Plngf a}uf/ Female ख쥍ु ला, दललत Surkhet Birendranagar bn axfb"/ a}uf/ /d]z a}uf/ 6 ANIL BISHWOKARMA असिल सिश्वकमाय Male ख쥍ु ला, दललत Salyan Marke VDC ^f]k axfb'/ ;"gf/ शासलकराम सिश्वकमाय 7 ANUP BISHWOKARMA cg"k ljZjsdf{ Male ख쥍ु ला, दललत Dang Deokhuri Gadhawa alx/f sfdL t]h] sfdL 8 ARBINA THARU clj{gf yf? Female ख쥍ु ला Bardiya Geruwa dga'emfjg yf? x]jtnfn yf? 9 BABITA PANGALI alatf k+ufnL Female ख쥍ु ला Surkhet Jarbuta dlg/fd k+ufnL ofd k|;fb k+ufnL 10 BHAKTA RAJ BHATTA eSt /fh e§ Male ख쥍ु ला Doti Ranagaun 6Lsf /fd e§ nId0f k||;fb e§ 11 BHANU BHAKTA ROKAYA भािभु क्त रोकार्ा Male ख쥍ु ला Bajura Himali उसजरे रोकार्ा चन्द्र बहादरु रोकार्ा 12 BHARAT NEPALI भरर् िेपाली Male ख쥍ु ला, दललत Surkhet Gutu राम स िं दमाई गाेेपाल स िं िेपाली 13 BHARAT RAWAL भरर् रािल Male ख쥍ु ला Mugu Khatyad RM जर् रु रािल जर्लाल रािल 14 BHUPENDRA BAHADUR CHAND e"k]Gb| axfb"/ rGb Male ख쥍ु ला Dailekh sinhasain etm -

Volume 43, No. 1 • June 2020

South Asian Journal of Policy and Governance Volume 43, No. 1 • June 2020 South Asian Journal of Policy and Governance i South Asian Journal of Policy and Governance (SJPG) Formerly Nepalese Journal of Public Policy and Governance Published in June 2020 Copyright@2020. All rights reserved Published Biannually jointly by South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance (SIPG), North South University, Bangladesh and Central Department of Public Administration, Tribhuvan University, Nepal Cover, Design and Layout : Mahfuz Printed in Dhaka in June 2020 South Asian Journal of Policy and Governance (SJGP) is jointly published biannually by South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance (SIPG) Room No - NAC 1074, Phone: +88-02-55668200 Ext. 2163/2164 www.sipg.northsouth.edu, [email protected] and Central Department of Public Administration (CDPA) Balkhu, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: +977-1-4671192, Fax: +977-1-4276887 E-mail: [email protected], URL: http://sjpgjournal.org PATRON SJPG Advisory Board Hari Bhakta Shahi Salahuddin M. Aminuzzaman Campus Chief, Public Administration Campus North South University, Bangladesh Tribhuvan University, Nepal Farhad Hossain The University of Manchester, United Kingdom SJPG Editorial Board Steinar Askvik Tek Nath Dhakal University of Bergen, Norway Editor-in-Chief, Tribhuvan University, Nepal Per Lægreid Ishtiaq Jamil University of Bergen, Norway University of Bergen, Norway Dili Raj Sharma Rizwan Khair Dean, Tribhuvan University, Nepal Managing Editor, North South University, Bangladesh Prachanda Pradhan M. Mahfuzul -

Budget Analysis of Ministry of Health and Population FY 2018/19

Budget Analysis of Ministry of Health and Population FY 2018/19 Federal Ministry of Health and Population Policy Planning and Monitoring Division Government of Nepal September 2018 Recommended citation: FMoHP and NHSSP (2018). Budget Analysis of Ministry of Health and Population FY 2018/19. Federal Ministry of Health and Population and Nepal Health Sector Support Programme. Contributors: Dr. Bikash Devkota, Lila Raj Paudel, Muktinath Neupane, Hema Bhatt, Dr. Suresh Tiwari, Dhruba Raj Ghimire, and Dr. Bal Krishna Suvedi Disclaimer: All reasonable precautions have been taken by the Federal Ministry of Health and Population (FMoHP) and Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP) to verify the information contained in this publication. However, this published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of this material lies with the reader. In no event shall the FMoHP and NHSSP be liable for damages arising from its use. For the further information write to Hema Bhatt at [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to all the officials and experts for giving their time to discuss budget allocation and expenditure patterns. We value the inputs from the Federal Ministry of Health and Population (FMoHP), Department of Health Services, Divisions, and Centres. The study team would like to acknowledge Dr Pushpa Chaudhary, Secretary FMoHP, for her overall guidance while finalising this budget analysis. We are thankful to Dr. Guna Raj Lohani, Director General, DoHS for his support. We are thankful to provincial government and sampled Palikas for their support in providing the information. -

S.N Local Government Bodies EN स्थानीय तहको नाम NP District

S.N Local Government Bodies_EN थानीय तहको नाम_NP District LGB_Type Province Website 1 Fungling Municipality फु ङलिङ नगरपालिका Taplejung Municipality 1 phunglingmun.gov.np 2 Aathrai Triveni Rural Municipality आठराई त्रिवेणी गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 aathraitribenimun.gov.np 3 Sidingwa Rural Municipality लिदिङ्वा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sidingbamun.gov.np 4 Faktanglung Rural Municipality फक्ताङिुङ गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 phaktanglungmun.gov.np 5 Mikhwakhola Rural Municipality लि啍वाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 mikwakholamun.gov.np 6 Meringden Rural Municipality िेररङिेन गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 meringdenmun.gov.np 7 Maiwakhola Rural Municipality िैवाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 maiwakholamun.gov.np 8 Yangworak Rural Municipality याङवरक गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 yangwarakmuntaplejung.gov.np 9 Sirijunga Rural Municipality लिरीजङ्घा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sirijanghamun.gov.np 10 Fidhim Municipality दफदिि नगरपालिका Panchthar Municipality 1 phidimmun.gov.np 11 Falelung Rural Municipality फािेिुुंग गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalelungmun.gov.np 12 Falgunanda Rural Municipality फा쥍गुनन्ि गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalgunandamun.gov.np 13 Hilihang Rural Municipality दिलििाङ गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 hilihangmun.gov.np 14 Kumyayek Rural Municipality कु म्िायक गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 kummayakmun.gov.np 15 Miklajung Rural Municipality लि啍िाजुङ गाउँपालिका -

Annual Report 2074-075

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2074/75 | 17/18 Sanothimi, Bhaktapur, Nepal Website: http://www.ugcnepal.edu.np UN IV ERSITY E-mail: [email protected] UNIV ERSITY GRANTS Post Box: 10796, Kathmandu, Nepal GRANTS Phone: (977-1) 6638548, 6638549, 6638550 COMMISSION Fax: 977-1-6638552 COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2074/75 17/18 UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION (UGC) Sanothimi, Bhaktapur, Nepal Website: www.ugcnepal.edu.np ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS BPKISH B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences CEDA Centre for Economic Development and Administration CERID Research Centre for Educational Innovation and Development CNAS Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies DoE Department of Education GoN Government of Nepal HEMIS Higher Education Management Information System EMIS Education Management Information System HSEB Higher Secondary Education Board IAAS Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences IDA International Development Association IoE Institute of Engineering IoF Institute of Forestry IoM Institute of Medicine IoST Institute of Science and Technology J&MC Journalism and Mass Communication KU Kathmandu University LBU Lumbini Buddha University NAMS National Academy of Medical Science NPU Nepal Public University NSU Nepal Sanskrit University PAD Project Appraisal Document PAHS Patan Academy of Health Sciences PokU Pokhara University PRT Peer Review Team PU Purbanchal University QAA Quality Assurance and Accreditation QAAC Quality Assurance and Accreditation Committee RBB Rashtriya Banijya Bank RECAST Research Centre for Applied Science and Technology SFAFD Student Financial Assistance Fund Development SFAFDB Student Financial Assistance Fund Development Board SHEP Second Higher Education Project RMC Research Management Cell SSR Self-Study Report TU Tribhuvan University TUCL TU Central Library UGC University Grants Commission CONTENTS SECTION I: UGC, NEPAL: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION ..................................................... -

Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal

ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Before After 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Authors Binod Sharma, Santosh Nepal, Dipak Gyawali, Govinda Sharma Pokharel, Shahriar Wahid, Aditi Mukherji, Sushma Acharya, and Arun Bhakta Shrestha International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, June 2016 i Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2016 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Nepal EGRP-RFP-FY19-P006

Request for Proposal (RFP) - Nepal EGRP-RFP-FY19-P006 Amendment #1 Commodity/Service Required: Endline Assessment of Early Grade Reading Program (EGRP) Type of Procurement: One Time Purchase Order Type of Contract: Firm Fixed Price Term of Contract: December 01, 2019- April 15, 2020 Contract Funding: AID-367-TO-15-00002 This Procurement supports: USAID’s Early Grade Reading Program (EGRP) Submit Proposal to: The Selection Committee RTI- USAID Early Grade Reading Program House no. 46/64, Uttar Dhoka, Lazimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal Original Date of Issue of RFP: Tuesday, July 23, 2019 Date Questions from Supplier Due: Wednesday, July 31, 2019 11:00 a.m. Nepal Standard Time email [email protected] Note:- Q&A will be posted on RTI website Pre-submission conference on RFP Thursday, August 01, 2019, 10:00 to 11:00 AM at EGRP meeting hall, Lazimpat. Date Proposal Due: Thursday, August 22, 2019, 11:00 a.m. Nepal Standard Time Approximate Purchase Order effective date to December 01, 2019 Successful Bidder(s): Method of Submittal: Hard Copy of proposal along with the soft copy in a CD or pen drive. Proposal documents should be submitted in a closed envelope with wax seal (laah chhap) and clearly marked with the solicitation number to the following address: The Selection Committee RTI-USAID Early Grade Reading Program House no. 46/64, Uttar Dhoka, Lazimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal. Bidder’s quote must be printed on the organization’s letterhead, signed, stamped, dated and must include all items and/or services. In addition, each and every pages of the proposal documents needs to be signed and stamped by the authorized person in order to be considered for evaluation.