Palestinians in Syria and the Syrian Uprising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relational Processes in Ayahuasca Groups of Palestinians and Israelis

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 19 May 2021 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.607529 Relational Processes in Ayahuasca Groups of Palestinians and Israelis Leor Roseman 1*, Yiftach Ron 2,3, Antwan Saca, Natalie Ginsberg 4, Lisa Luan 1, Nadeem Karkabi 5, Rick Doblin 4 and Robin Carhart-Harris 1 1Centre for Psychedelic Research, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Faculty of Social Sciences, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, 3School of Creative Arts Therapies, Kibbutzim College, Tel Aviv, Israel, 4Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), Santa Cruz, CA, United States, 5Anthropology Department, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel Psychedelics are used in many group contexts. However, most phenomenological research on psychedelics is focused on personal experiences. This paper presents a phenomenological investigation centered on intersubjective and intercultural relational processes, exploring how an intercultural context affects both the group and individual process. Through 31 in-depth interviews, ceremonies in which Palestinians and Israelis Edited by: Alex K. Gearin, drink ayahuasca together have been investigated. The overarching question guiding this Xiamen University, China inquiry was how psychedelics might contribute to processes of peacebuilding, and in Reviewed by: particular how an intercultural context, embedded in a protracted conflict, would affect the Ismael Apud, group’s psychedelic process in a relational sense. Analysis of the interviews was based on University of the Republic, Uruguay Olivia Marcus, -

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Report Enigma of 'Baqiya Wa Tatamadad'

Report Enigma of ‘Baqiya wa Tatamadad’: The Islamic State Organization’s Military Survival Dr. Omar Ashour* 19 April 2016 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies Tel: +974-40158384 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.n The Islamic State (IS) organization's military survival is an enigma that has yet to be fully explained, but even defeating it militarily will only address what is just one of the symptoms of a much larger regional political crisis [Associated Press] Abstract The Islamic State organization’s motto, ‘baqiya wa tatamadad’, literally translates to ‘remaining and expanding’. Along these lines, this report examines the reality of the Islamic State organization’s continued military survival despite being targeted by much larger domestic, regional and international forces. The report is divided into three sections: the first reviews security and military studies addressing theoretical reasons for the survival of militarily weaker players against stronger parties; the second focuses on the Islamic State (IS) organisation’s military capabilities and how it uses its power tactically and strategically; and the third discusses the Arab political environment’s crisis, contradictions in the coalition’s strategy to combat IS and the implications of this. The report argues that defeating the IS organization militarily may temporarily treat a symptom of the political crisis in the region, but the crisis will remain if its roots remain unaddressed. Background After more than seven months of the US-led air campaign on the Islamic State organization and following multiple ground attacks by various (albeit at times conflicting) parties, the organisation has managed not only to survive but also to expand. -

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

The Palestinian Refugee Issue

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 238 Israeli-Lebanese Negotiations: The Palestinian Refugee Issue Dec 28, 1999 Brief Analysis yrian foreign minister Faruq al-Shara's recent announcement that Damascus and Beirut will sign peace S treaties with Israel together is not surprising, considering Syria's hegemony in Lebanon. But while Israel, Syria, and the United States have expressed guarded optimism about the latest resumption of peace talks, Lebanon has been more reserved in its enthusiasm. This is mainly due to its concern over the final disposition of the Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon. Hostile Minority Under Siege According to United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) figures, there are approximately 350,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon (about 9 percent of the country's total resident population). The refugees have long been viewed with suspicion by their Lebanese hosts, who cite the delicate sectarian balance in the country, heavy Palestinian involvement in the Lebanese civil war, and the military attacks that provoked the Israeli invasions of 1978 and 1982, as justification for their spurning of the refugees. Although no national census has been held in decades, available evidence indicates that the country is 70 percent Muslim and 30 percent Christian. The longstanding conflict between and among the various Muslim and Christian sects led to the explosion of the Lebanese civil war of 1975-89. Their differences--papered over in the 1989 Ta'if agreement which is designed to guarantee representation of each group and subgroup in specific positions in the government–remain pronounced. The Lebanese government rejects the integration of the refugees into the country, largely because it would upset whatever balance exists between religious and ethnic communities. -

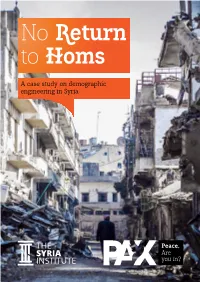

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY the Syrian Conflict: Through the Lens of Realpolitik by Alexander Ortiz a Thesis Submitted in Part

LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY The Syrian Conflict: Through the Lens of Realpolitik By Alexander Ortiz A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in International Affairs School of Arts and Sciences January 2014 To loved ones v Acknowledgments To Professors Salamey, Skulte-Ouasis, and Baroudi. Thank You for everything. Your guidance and help over the length of the program has been much appreciated. To Professor Rowayheb, thank you for being on my thesis board. vi The Syrian Conflict: Through the Lens of Realpolitik Alexander Ortiz Abstract This thesis examines power relations in the security vacuum created by the Syrian conflict. The conflicting nature of Syrian domestic politics has created a political stalemate that needs outside support to be resolved. Inaction on the part of the greater international community has allowed for regional powers to become highly entrenched in the conflict. Regional involvement and the demographics of Syrian parties have been used by popular mediums to describe the conflict as sectarian by nature. The central point of this thesis is to show that the veneer of sectarianism by all parties, both Syrian and regional, is primarily a by-product of competitive self-interest. This is done by showing that the relationships made between Syrian groups and their patrons are based on self-interest and the utility provided in these temporary unions. The seminal political theories of Locke and Hobbes concerning the foundations of political power show the Syrian groups to be acting upon political necessity, not sect. The ambitions of regional powers are analyzed through realist theory to explain power relations in an unregulated political environment both in Syria and in the region. -

General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/58/837–S/2004/465 General Assembly Distr.: General Security Council 8 June 2004 Original: English General Assembly Security Council Fifty-eighth session Fifty-ninth year Agenda items 37 and 156 The situation in the Middle East Measures to eliminate international terrorism Identical letters dated 8 June 2004 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Israel to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council I wish to draw your attention to the latest violations of the Blue Line from Lebanese territory. Yesterday morning, 7 June 2004, six 107-mm missiles were fired from Lebanese territory at an Israeli naval vessel patrolling in Israeli territorial waters. Four of the rockets hit Israeli territory, south of the Israeli-Lebanese border, just meters from the Israeli town of Rosh Hanikra. The rockets also gravely endangered the safety and security of UNIFIL personnel stationed in the area. Israeli security forces identified the source of the rocket fire as Ahmed Jibril’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a Damascus-based Palestinian terrorist organization operating in southern Lebanon. Israeli aircraft responded to these attacks by measured defensive action, in accordance with its right and duty of self-defense, against a PFLP terrorist base located near Beirut, which is used as a platform for terrorist activity in Lebanon. No injuries resulted from this defensive measure. This afternoon, 8 June 2004, Hizbullah terrorists perpetrated a heavy mortar attack from Lebanon across the Blue Line, wounding an Israeli soldier in the Har Dov region. -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return Eliza Wincombe Cornwell Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Cornwell, Eliza Wincombe, "Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 367. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/367 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Eliza Cornwell Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Michelle Murray and Dina Ramadan for unending support and encouragement throughout my time at Bard. I would also like to thank Kevin Duong for helping me formulate my ideas, for inspiring me to write and re-write, and for continuously giving me a sense of purpose and accomplishment in completing this project. -

Campaign to Delegitimize Israel

The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center June 1, 2011 Anti-Israeli organizations examine implementing propaganda displays based on flying large numbers of activists to Ben-Gurion Airport on commercial flights. They seek to express solidarity with the Palestinians, embarrass Israel and impress the "right of return" on international public opinion. Hamas urged "Palestinian refugees" to fly to Israel's airports for Naksa Day. Announcement issued by a group of anti-Israeli organizations and activists from the territories and around the globe calling for people to arrive at Israel's Ben-Gurion International Airport on July 8, 2011, and from there to go to Judea and Samaria for a week of solidarity with the Palestinians. It reads "Welcome to Palestine. Join us or help us? How to contribute?" and an email address (From the bienvenuepalestine.com website). קל 118-11 2 Overview 1. Anti-Israeli Palestinian and Western organizations participating in the campaign to delegitimize Israel are apparently preparing various types of anti-Israeli propaganda displays, using Israel's Ben-Gurion International Airport as their stage. Their objectives are to show solidarity with the Palestinians, embarrass Israel and raise international public consciousness for the so-called "right of return." The various groups and networks regard the displays as an alternative and counterweight to the flotilla currently being organized, whose goal ("lifting the siege of the Gaza Strip") they regard as "too narrow" (their goals is "lifting the siege from all Palestine"). 2. A call was recently posted on Hamas' main website for "Palestinian refugees" to take regular commercial flights to Israel's airports (referred to as the airports of "Palestine occupied since 1948") on June 4 or 5 as part of the events of Naksa Day (the day commemorating the Arab defeat in the Six Day War) (Palestine-info website, May 28, 2011).