Higher Education Management and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Education Finance and Cost Sharing in Nigeria: Considerations for Policy Direction

0 University Education Finance and Cost Sharing in Nigeria: Considerations for Policy Direction 1Maruff A. Oladejo, 2Gbolagade M. Olowo, & 3Tajudeen A. Azees 1Department of Educational Management, University of Lagos, Akoka, 2Department of Educational Foundations, Federal College of Education (Sp), Oyo 3Department of Curriculum & Instructions, Emmanuel Alayande College of Education, Oyo 0 1 Abstract Higher education in general and university education in particular is an educational investment which brings with it, economic returns both for individuals and society. Hence, its proper funding towards the attainment of its lofty goals should be the collective responsibility of every stakeholders. This paper therefore discussed university education finance and cost sharing in Nigeria. The concepts of higher education and higher education finance were examined, followed by the philosophical and the perspectives of university education in Nigeria. The initiative of private funding of education vis-à-vis Tertiary Education Trust Fund (Tetfund) was brought to the fore. The paper further examined cost structure and sharing in Nigerian university system. It specifically described cost sharing as a shift in the burden of higher education costs from being borne exclusively or predominately by government, or taxpayers, to being shared with parents and students. Findings showed that Tetfund does not really provide for students directly. As regards students in private universities in Nigeria, and that private sector has never been involved in funding private universities. It was recommended among others that there is the need to re-engineer policies that will ensure effective financial accountability to prevent fiscal failure in Nigerian higher educational institutions, as well as policies which will ensure more effective community and individual participation such that government will be able to relinquish responsibility for maintaining large parts of the education system. -

Nigerian University System Statistical Digest 2017

Nigerian University System Statistical Digest 2017 Executive Secretary: Professor Abubakar Adamu Rasheed, mni, MFR, FNAL Nigerian University System Statistical Digest, 2017 i Published in April 2018 by the National Universities Commission 26, Aguiyi Ironsi street PMB 237 Garki GPO, Maitama, Abuja. Telephone: +2348027455412, +234054407741 Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-965-138-2 Nigerian University System Statistical Digest by the National Universities Commission is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.nuc.edu.ng. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at www.nuc.edu.ng. Printed by Sterling Publishers, Slough UK and Delhi, India Lead Consultant: Peter A. Okebukola Coordinating NUC Staff: Dr. Remi Biodun Saliu and Dr. Joshua Atah Important Notes: 1. Data as supplied and verified by the universities. 2. Information in this Statistical Digest is an update of the Statistical Annex in The State of University Education in Nigeria, 2017. 3. N/A=Not Applicable. Blanks are indicated where the university did not provide data. 4. Universities not listed failed to submit data on due date. Nigerian University System Statistical Digest, 2017 ii Board of the National Universities Commission Emeritus Professor Ayo Banjo (Chairman) Professor Abubakar A. Rasheed (Executive Secretary) Chief Johnson Osinugo Hon. Ubong Donald Etiebet Dr. Dogara Bashir Dr. Babatunde M Olokun Alh. Abdulsalam Moyosore Mr. Yakubu Aliyu Professor Rahila Plangnan Gowon Professor Sunday A. Bwala Professor Mala Mohammed Daura Professor Joseph Atubokiki Ajienka Professor Anthony N Okere Professor Hussaini M. Tukur Professor Afis Ayinde Oladosu Professor I.O. -

Usage of Web 2.0 Tools by Academic Librarians

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2017 Usage of Web 2.0 Tools by Academic Librarians: A case study of University Libraries in South-South Nigeria Gloria Ogheneghatowho Oyovwe-Tinuoye University Library, Federal University of Petroleum Resources, Effurun, Nigeria, [email protected] Dorcas Ejemeh Krubu Dr Department of Library and Information Science, Ambrose Alli University Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria, [email protected] Osaze Patrick Ijiekhuamhen University Library, Federal University of Petroleum Resources, Effurun, Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Oyovwe-Tinuoye, Gloria Ogheneghatowho; Krubu, Dorcas Ejemeh Dr; and Ijiekhuamhen, Osaze Patrick, "Usage of Web 2.0 Tools by Academic Librarians: A case study of University Libraries in South-South Nigeria" (2017). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1643. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1643 Usage of Web 2.0 Tools by Academic Librarians: A case study of University Libraries in South-South Nigeria By Oyovwe-Tinuoye, Gloria Ogheneghatowho Circulation Department, Federal University of Petroleum Resources, Effurun [email protected] Krubu Dorcas Krubu, PhD Department of Library and Information Science, Ambrose Alli University Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria [email protected] Ijiekhuamhen Osaze Patrick Circulation Department, Federal University of Petroleum Resources, Effurun [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate awareness and use of Web 2.0 tools by librarians in university libraries in South- South Nigeria. This study adopted a descriptive survey research design. Purposive sampling technique was used based on the researcher’s discretion, there are 21 university libraries in South-south, Nigeria but the researchers used 16 universities out of the total numbers because of the large scope and financial implication to cover the total population. -

Private Universities in Nigeria – the Challenges Ahead

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Afe Babalola University Repository American Journal of Scientific Research ISSN 1450-223X Issue 7 (2010), pp.15-24 © EuroJournals Publishing, Inc. 2010 http://www.eurojournals.com/ajsr.htm Private Universities in Nigeria – the Challenges Ahead Ajadi, Timothy Olugbenga School of Education, National Open University of Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Public universities had a near monopoly in providing university education in Nigeria until 1999. The market-friendly reforms initiated under the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP), the deregulation policies, and the financial crisis of the states created an encouraging environment for the emergence of the private universities in Nigeria. The legislative measures initiated to establish private universities in Nigeria also helped the entry of cross-border education, which is offered mainly through private providers. At present the private sector is a fast expanding segment of university education in Nigeria, although it still constitutes a small share of enrolment in university education. The paper attempts to analyse the growth, expansion, justification and the challenges of private universities in Nigeria. Keywords: Private universities, public universities, access, globalization, social demand, academic staff. Introduction In many African countries, the provision of University education by private institutions is a growing phenomenon when compared to other parts of the world; however, most African countries have been slow to expand the private sector in University education (Altbach, 1999). So also in Nigeria, the emergence of private universities as a business enterprise is an emerging phenomenon, a number of issues plague its development including legal status, quality assurance and the cost of service. -

Reaching Adventist Students in Secular Campuses With

The History of Private Sector Participation in University Education in Nigeria (1989-2012) Omomia O. Austin Omomia T. A. James Adeyemi Oluwatoyin Babalola ABSTRACT—There has been a consistent quest for higher education (especially university) in Nigeria due to the unstable academic system, coupled with the total number of candidates seeking admission into the various higher institutions in Nigeria yearly. On the basis of this, it has become obvious that the existing higher institutions, which were mainly government-owned, cannot cope with the ever increasing demand for higher education in Nigeria. One of the basic solutions to this challenge is the liberalization of participation in the education sector. The study applied both historical and sociological methodology in its investigation. This study examined the history of higher education in Nigeria, from 1989 to 2012. In addition, it also examined the role played by the private sector in the Nigerian educational sector in this present dispensation. The writers recommended that there should be a consistent upsurge of private higher institutions in Nigeria to adequately address the challenge posed by high prospective students’ demand for university education. This is due to the fact that the government alone cannot handle the ever increasing demand for higher education in Nigeria. Manuscript received June 2, 2014; revised August 1, 2014; accepted August 25, 2014. Omomia O. Austin ([email protected]) is with Department of Religious Studies, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria. He is a Nigerian by nationality. Omomia T. A. ([email protected]) is with the Department of Educational Foundations, Sholle of Technical Education, Yaba College of Technology, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. -

Percentage of Special Needs Students

Percentage of special needs students S/N University % with special needs 1. Abia State University, Uturu 4.00 2. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi 0.00 3. Achievers University, Owo 0.00 4. Adamawa State University Mubi 0.50 5. Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba 0.08 6. Adeleke University, Ede 0.03 7. Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti - Ekiti State 8. African University of Science & Technology, Abuja 0.93 9. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 0.10 10. Ajayi Crowther University, Ibadan 11. Akwa Ibom State University, Ikot Akpaden 0.00 12. Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike, Ikwo 0.01 13. Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin 0.00 14. Al-Qalam University, Katsina 0.05 15. Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma 0.03 16. American University of Nigeria, Yola 0.00 17. Anchor University Ayobo Lagos State 0.44 18. Arthur Javis University Akpoyubo Cross River State 0.00 19. Augustine University 0.00 20. Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo 0.12 21. Bayero University, Kano 0.09 22. Baze University 0.48 23. Bells University of Technology, Ota 1.00 24. Benson Idahosa University, Benin City 0.00 25. Benue State University, Makurdi 0.12 26. Bingham University 0.00 27. Bowen University, Iwo 0.12 28. Caleb University, Lagos 0.15 29. Caritas University, Enugu 0.00 30. Chrisland University 0.00 31. Christopher University Mowe 0.00 32. Clifford University Owerrinta Abia State 0.00 33. Coal City University Enugu State 34. Covenant University Ota 0.00 35. Crawford University Igbesa 0.30 36. Crescent University 0.00 37. Cross River State University of Science &Technology, Calabar 0.00 38. -

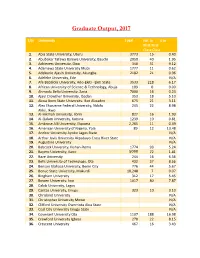

Graduate Output, 2017

Graduate Output, 2017 S/N University Total No. In % in First First Class Class 1. Abia State University, Uturu 3773 15 0.40 2. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi 2050 40 1.95 3. Achievers University, Owo 340 31 9.12 4. Adamawa State University Mubi 1777 11 0.62 5. Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba 2182 21 0.96 6. Adeleke University, Ede N/A 7. Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti - Ekiti State 3533 218 6.17 8. African University of Science & Technology, Abuja 109 0 0.00 9. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 7000 16 0.23 10. Ajayi Crowther University, Ibadan 353 18 5.10 11. Akwa Ibom State University, Ikot Akpaden 675 21 3.11 12. Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu 245 22 8.98 Alike, Ikwo 13. Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin 827 16 1.93 14. Al-Qalam University, Katsina 1239 10 0.81 15. Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma 2,265 11 0.49 16. American University of Nigeria, Yola 89 12 13.48 17. Anchor University Ayobo Lagos State N/A 18. Arthur Javis University Akpabuyo Cross River State N/A 19. Augustine University N/A 20. Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo 1774 93 5.24 21. Bayero University, Kano 5098 72 1.41 22. Baze University 244 16 6.56 23. Bells University of Technology, Ota 432 37 8.56 24. Benson Idahosa University, Benin City 776 44 5.67 25. Benue State University, Makurdi 10,248 7 0.07 26. Bingham University 312 17 5.45 27. Bowen University, Iwo 1017 80 7.87 28. -

By Hadiza Hafiz, Ph.D

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 7 No. 9 September 2019 FACTORS HINDERING ACCESS TO UNIVERSITY EDUCATION: IMPLICATION FOR ADMISSION IN NIGERIAN UNIVERSITIES By Hadiza Hafiz, Ph.D Department of Arts and Social Science Education, Faculty of Education Yusuf Maitama Sule University, Kano-Nigeria [email protected] Abstract University education being the basic instrument of economic growth and technological advancement in any country, demand for it has increased due to the recent policy of universal, free and compulsory education at the basic levels and also as a result of an increase in the college-age population, as well as an awareness of the role of university education in the development of the individual and the nation in general. This paper, therefore, examines issues and challenges of securing admission to Universities in Nigeria. To do this, efforts were made to examine the operation of university education in Nigeria, the concept of access in education, the federal government policies on admission, major factors that influence and impede access to university among others were discussed in the paper. In conclusion the paper revealed that despite the increase in the number of universities, the rate of admission is low compared to the number of applicants. This is as a result of impediments to access and management of admission in the universities. Based on that, the paper recommends for the establishment of more universities to meet the needs of those yearning for University education. More academic staff should be employed, and to make admission twice in a year as it has been done in many countries. -

MB 13Th Jan 2020

RSITIE VE S C NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES COMMISSION NI O U M L M A I S N S O I I O T N A N T E HO IC UG ERV HT AND S MONDAA PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Y www.nuc.edu.ng th 0795-3089 13 January, 2020 Vol. 15 No. 2 We’re Making NUS More Innovative —— Prof. Rasheed lists reforms h e E x e c u t i v e While reviewing the activities repositioning agenda of NUC, Secretary, National of the Commission in the past the university system had in TU n i v e r s i t i e s Commission (NUC), Professor Abubakar Rasheed, mni, MFR, FNAL, has reaffirmed that the Commission was committed to ensuring that Nigerian University System ( N U S ) b e c a m e m o r e innovative and research- oriented. In his new year message, Prof. Rasheed expressed profound appreciation to the President, Federal Republic of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari, GCFR, the National Assembly, Federal Ministry of Education, NUS and other stakeholders in Chairman, NUC Board, Prof. Ayo Banjo and Executive Secretary, NUC, Prof. Abubakar Adamu Rasheed the education sector for the achievements recorded by the year, Professor Rasheed stated the past three years, been Commission in 2019. t h a t f o l l o w i n g t h e undergoing series of reforms in this edition NUC Unbundles NUC Approves Mass Communication FUT Minna Centre for Open Distance and Pg. 8 e-Learning Pg. 9 EDITORIAL BOARD: Ibrahim Usman Yakasai (Chairman), Mal. -

International Journal on Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS, Vol 16, No 1 March, 2020)||Gubdjournals.Org

International Journal on Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS, Vol 16, No 1 March, 2020)||gubdjournals.org THE HISTORY OF THE EMERGENCE OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES IN NIGERIA Simeon Emenike Weli, Ph.D. Faculty of Technical and Science Education, Rivers State University, Nkpolu Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Rivers State. Abstract The demand for university education became so great in Nigeria during and following the oil-boom era that existing universities in the country could not offer admission to all. This and other factors discussed in this work led to the deregulation of higher education to give room to private sector participation. This paper examined the history of the emergence of private universities in Nigeria. Introduction Private education is a reality and has been growing around the world together with globalization. Private universities are seen as the most vibrant and fastest growing sections of post secondary education in the 21st century (Altbach, 1999). These are some of the reasons why privatization of higher education is quick growing globally, especially in Nigeria. i. There are the deregulation policies of the governments on the provision of education and thus giving adequate opportunities for private participation in education. ii. There is the inability of the public sector to satisfy the growing social demand for higher education, hence the need for the private sector to expand students’ access to higher education. iii. Public education is criticized for inefficiency while the private sector is increasingly promoted for its efficiency in operation. iv. The demand for employment oriented courses and subjects of study had changed and public universities seem unable to respond adequately to this phenomenon, hence it becomes imperative that private sector should increase. -

Ican Accreditated Tertiary Institutions Updated on May 28, 2020

THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF NIGERIA ICAN ACCREDITATED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS UPDATED ON MAY 28, 2020. Note: Students who graduated after the sessions covered in the accreditation from the Institutions highlighted in ‘RED’ will no longer enjoy exemption benefits until the accreditation is revalidated UNIVERSITIES New due Year of first Sessions covered session for re- S/N Name of Institution accreditation in accreditation Remark accreditation 1 Abia State University, Uturu 1987 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 2 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 2016/2017 3 Achievers University , Owo, Ondo State 2010 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 4 Adamawa State University, Mubi Adamawa State 2008 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 5 Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State 2007 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 6 Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State 2017 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 7 Afe Babalola University ,Ado- Ekiti 2013 2016/2017 To 2019/2020 2020/2021 8 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State 1974 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 9 Ajayi Crowther University,Oyo State 2009 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 10 AL-Hikman University , Ilorin, Kwara State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 2016/2017 11 Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State 1994 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 12 American University Of Nigeria, Yola Adamawa State 2008 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 13 Babcock University, Ilishan, Ogun State 2003 2009/2010 T0 2012/2013 Under MCATI 14 Bayero University, Kano State -

ICAN Accredited Tertiary Institutions

THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF NIGERIA ICAN ACCREDITATED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS UPDATED ON JUNE 14, 2021. Note: Students who graduated after the sessions covered in the accreditation from the Institutions highlighted in ‘RED’ will no longer enjoy exemption benefits until the accreditation is revalidated UNIVERSITIES New due Year of first Sessions covered session for re- S/N Name of Institution accreditation in accreditation Remark accreditation 1 Abia State University, Uturu 1987 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 2 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 2016/2017 3 Achievers University , Owo, Ondo State 2010 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 4 Adamawa State University, Mubi Adamawa State 2008 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 5 Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State 2007 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 6 Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State 2017 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 7 Afe Babalola University ,Ado- Ekiti 2013 2016/2017 To 2019/2020 2020/2021 8 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State 1974 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 9 Ajayi Crowther University,Oyo State 2009 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 10 AL-Hikman University , Ilorin, Kwara State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 Under MCATI 2016/2017 11 Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State 1994 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 12 American University Of Nigeria, Yola Adamawa State 2008 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 13 Babcock University, Ilishan, Ogun State 2003 2009/2010 T0 2012/2013 Under MCATI 14 Bayero University,