An Autocratic Approach to Music Copyright?: the Means Through Which Frank Zappa Translated and Adapted Both His Own and Other Composers’ Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here I Played with Various Rhythm Sections in Festivals, Concerts, Clubs, Film Scores, on Record Dates and So on - the List Is Too Long

MICHAEL MANTLER RECORDINGS COMMUNICATION FONTANA 881 011 THE JAZZ COMPOSER'S ORCHESTRA Steve Lacy (soprano saxophone) Jimmy Lyons (alto saxophone) Robin Kenyatta (alto saxophone) Ken Mcintyre (alto saxophone) Bob Carducci (tenor saxophone) Fred Pirtle (baritone saxophone) Mike Mantler (trumpet) Ray Codrington (trumpet) Roswell Rudd (trombone) Paul Bley (piano) Steve Swallow (bass) Kent Carter (bass) Barry Altschul (drums) recorded live, April 10, 1965, New York TITLES Day (Communications No.4) / Communications No.5 (album also includes Roast by Carla Bley) FROM THE ALBUM LINER NOTES The Jazz Composer's Orchestra was formed in the fall of 1964 in New York City as one of the eight groups of the Jazz Composer's Guild. Mike Mantler and Carla Bley, being the only two non-leader members of the Guild, had decided to organize an orchestra made up of musicians both inside and outside the Guild. This group, then known as the Jazz Composer's Guild Orchestra and consisting of eleven musicians, began rehearsals in the downtown loft of painter Mike Snow for its premiere performance at the Guild's Judson Hall series of concerts in December 1964. The orchestra, set up in a large circle in the center of the hall, played "Communications no.3" by Mike Mantler and "Roast" by Carla Bley. The concert was so successful musically that the leaders decided to continue to write for the group and to give performances at the Guild's new headquarters, a triangular studio on top of the Village Vanguard, called the Contemporary Center. In early March 1965 at the first of these concerts, which were presented in a workshop style, the group had been enlarged to fifteen musicians and the pieces played were "Radio" by Carla Bley and "Communications no.4" (subtitled "Day") by Mike Mantler. -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

Actes Intermédiaires De La Conférence ICE-Z 69

"Actes intermédiaires" de la 3ème Conférence Internationale de Zappologie (ICE-Z 69) Nous sommes en attente de la retranscription des interventions de Jean-Christophe Rabut, Philippe Mérigot, Jonathan Pontier et Serge Maestracci. Tous les textes présentés ici sont susceptibles d'être corrigés par leurs auteurs avant publication définitive en édition bilingue anglais-français. 14 juillet 2008 p.3 — Marco Belluzi (I) Une présentation de "New Mother, Old Dust", une re-création de "200 Motels" p.10 — Andy Hollinden (USA) "Everything Is Now: How Frank Zappa Illustrates The Universe" p.17 — suivi de la traduction en français par Michel Sage p.23 — Simon Prentis (UK) "As Above, So Below : One Size Fits All" p.29 — Dr Richard Hemmings (UK) "Conceptual Wazoos : Kazoo Concepts : Whizzle-whizzle" p.34 — Paul Sutton (UK) “God bless America!”: Frank Sinatra and the Mothers of Invention p.43 — Pacôme Thiellement (F) "De la guerre : Continuité Conceptuelle, Freaks, Polices du cerveau et Mutations Unies" p.49 — suivi de la traduction en anglais par Michel Sage p.54 — Ben Watson (UK) "Anti-Zappa, Or, not getting the point : the "French problem" Marco Belluzi (I) Une présentation de "New Mother, Old Dust", une re-création de "200 Motels" NEW MOTHER, OLD DUST Musical Phantazie on Frank V. Zappa's '200 MOTELS’ Original Soundtrack (United Artists, 1971) A shameless description for the 3rd International Conference of Esemplastic Zappology (ICE_Z) Paris, 5th ‐ 6th July 2008 by Alessandro Tozzi & Marco Belluzzi ‐ ‐ ‐ INTRODUCTION In primis et ante omnia [first of all and before everything], let's give ourselves up to the ineffable pleasure to thank you all for having given two wandering musicians as we are, such a high‐level opportunity to introduce this specimen of our work. -

Frankly, It's Dweezil

AI Z BON R. M Frankly, It’s Dweezil By mr. Bonzai he year 2006 has shaped up to be a big one for Dweezil Zappa. He’s releasing his first solo album since 2000’s Automatic (Favored Nations), he completely remodeled the control room T of the renowned Zappa studio—the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen—and he launched a full-scale tour of entirely Frank Zappa compositions, called “Zappa Plays Zappa” (aka the Zappa the “Tour de Frank”). Joining the touring band are Frank Zappa alumni Steve Vai, Terry Bozzio, and Napoleon Murphy Brock (see Fig. 1). younger on Dweezil and I met in the studio as he was finishing two months of rehearsals and putting the final touches on the album,Go with What You Know (Zappa Records, 2006; see Fig. 2), which engineering his comprises Dweezil’s compositions as well as Frank Zappa’s “Peaches en Regalia,” a tune origi- nally recorded in 1969 and altered in 2006 with the Dweezil touch. The album will be released new CD, revamp- during the final leg of the tour, which stretches throughout Europe and America. ing his dad’s I was listening to you playing a part that Frank wrote. Is that in preparation for your tour? studio, and the Yes, we are preparing for the “Zappa Plays Zappa” tour. It’s the first official event that we’ve been able to put together where we’re actually going to go out and play Frank’s “Tour de Frank.” music. We’ll have other elements as well. The 25-minute opening of the concert will include excerpts from a documentary film about Frank’s work as a composer as well as some rare FZ concert footage. -

Fr, 15.5. Cadre De La « Semaine De La Créativité Et De L’Innovation »

2 AGENDA woxx | 15 05 2009 | Nr 1006 WAT ASS LASS I 15.05. - 24.05. WAT ASS LASS? Rockapella – der Name ist Programm: Die fünfköpfige Band unterhält ihr Publikum an diesem Freitag, dem 15. Mai im Trifolion in Echternach mit einer explosiven Mischung aus Rock, Pop und Groove, gewürzt mir einem Schuss Virtuosität. (Kirchberg), Luxembourg, 20h. Dans le FR, 15.5. cadre de la « Semaine de la Créativité et de l’innovation ». JUNIOR MUSEK Kidscity - construire la ville de demain, ateliers pour enfants de 6 à Rockapella, Trifolion, Echternach, 12 ans, Luxexpo, stand de la Fondation 20h. Tel. 47 08 95-1. de l’Architecture et de l’Ingénierie, Luxembourg, 14h - 16h. El grito el silencio, rencontre de Tél. 43 62 63-1 ou bien courriel : la musique persane et du cante [email protected] flamenco, Kulturfabrik, Esch, 20h. Tél. 55 44 93-1. Dans le cadre du 4e KONFERENZ Flamenco Festival. Wer hat Angst vor schwulen Ismène, opéra pour voix seule, inspiré Jungs? Homophobie in der par le poème homonyme de Yannis Schule, Podiumsdiskussion mit Ritsos, avec Marianne Pousseur, Grand anschließender Vorführung des Films Théâtre, Luxembourg, 20h. „Get Real“, Broadway-Filmpalast, Trier, Tél. 47 08 95-1. 18h. Im Rahmen des International Day Against Homophobia. Music Maker Blues Foundation Revue, Philharmonie, Salle de WAT ASS LASS LX architecture - au coeur de musique de chambre, Luxembourg, Kalender S. 2 - S. 10 l’Europe, architecture contemporaine 20h. Tél. 26 32 26 32. Zappa plays Zappa S. 4 au Luxembourg, Luxexpo, espace théâtre, Luxembourg, 18h30. Dans le Orchestre Philharmonique du Erausgepickt S. -

Zappa Et Le Cinéma Zappa and Film

Volume ! La revue des musiques populaires 3 : 0 | 2004 Rock et Cinéma Zappa et le cinéma Zappa and Film Sylvain Siclier Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/volume/2181 DOI : 10.4000/volume.2181 ISSN : 1950-568X Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 janvier 2004 Pagination : 123-132 ISBN : 1634-5495 ISSN : 1634-5495 Référence électronique Sylvain Siclier, « Zappa et le cinéma », Volume ! [En ligne], 3 : 0 | 2004, mis en ligne le 30 août 2006, consulté le 10 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/volume/2181 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/volume.2181 L'auteur & les Éd. Mélanie Seteun Sylvain SICLIER, « Zappa et le cinéma », Volume ! La revue des musiques populaires, hors-série n° 1, 2004, p. 123-132. Éditions Mélanie Seteun 123 Zappa et le cinéma par Sylvain SICLIER Journaliste Résumé. La figure de Zappa reste une référence pour de nombreux amateurs et artistes. Sylvain Siclier examine les liens du compositeur/guitariste avec le cinéma, les usages et les détournements qu’il en a fait. La conclusion est évidente : le dialogue n’a jamais cessé. Volume! Hors-Série I Volume! 124 Sylvain Siclier Zappa et le cinéma 125 ositeur, guitariste, parolier, chef d’orchestre et producteur, Frank Zappa, mort le Comp4 décembre 1993, a aussi été réalisateur ou initiateur d’une poignée de courts et moyens métrages – des documents sur son activité de musicien – et de trois longs métrages, dont deux, 200 Motels (1971) et Baby Snakes (1979) ont trouvé une exploitation en salles. Cette relation de Zappa au cinéma ne se contente toutefois pas de cette partie visible. -

The Mothers of Invention Uncle Meat Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Mothers Of Invention Uncle Meat mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Rock Album: Uncle Meat Country: Canada Released: 1969 Style: Musique Concrète, Avantgarde, Fusion, Doo Wop, Experimental, Parody MP3 version RAR size: 1764 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1989 mb WMA version RAR size: 1822 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 329 Other Formats: APE AUD MMF VOC AC3 AHX WMA Tracklist A1 Uncle Meat: Main Title Theme 1:54 A2 The Voice Of Cheese 0:27 A3 400 Days Of The Year 5:56 A4 Zolar Czakl 0:57 A5 Dog Breath, In The Year Of The Plague 5:51 A6 The Legend Of The Golden Arches 1:24 A7 Louie Louie (At The Royal Albert Hall In London) 2:28 A8 The Dog Breath Variations 1:36 B1 Sleeping In A Jar 0:49 B2 Our Bizarre Relationship 1:05 B3 The Uncle Meat Variations 4:40 B4 Electric Aunt Jemima 1:53 B5 Prelude To King Kong 3:24 B6 God Bless America (Live At The Whisky A Go Go) 1:22 B7 A Pound For A Brown On The Bus 1:29 B8 Ian Underwood Whips It Out (Live On Stage In Copenhagen) 5:08 C1 Mr. Green Genes 3:10 C2 We Can Shoot You 1:48 C3 "If We'd All Been Living In California . " 1:29 C4 The Air 2:57 C5 Project X 4:47 C6 Cruising For Burgers 2:19 D1 King Kong Itself (As Played By The Mothers In A Studio) 0:53 D2 King Kong (Its Magnificence As Interpreted By Dom DeWild) 1:15 D3 King Kong (As Motorhead Explains It) 1:44 D4 King Kong (The Gardner Varieties) 6:17 D5 King Kong (As Played By 3 Deranged Good Humor Trucks) 0:29 King Kong (Live On A Flat Bed Diesel In The Middle Of A Race Track At A Miami Pop D6 7:25 Festival . -

Statesman Contacted Mccoy and Letter

AO e- I-) r Sa- "I',) MIONDAY OCTOBER 28 1974 Stony Brook, New York Volume 18 Number 19 Distributedfree of charge throughout campus and community every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday <______________~~~~~.^ He . - r el----------'-, ---- IN 00, Mount Dedication; I Communications Major The Suffolk Museum dedicated its new Fine Arts building yesterday. I Housed in the new building is the I May Begin in September largest collection of William Sidney By MARY PAT SCHROEDER political sdence cou_, ch Mount paintings in existence. The and DAVID GILMAN 'Political PKganda and sow dedication was highlighted by the The Stony Brook Communications socoogy c such as "Ma acceptance by Mrs. Ward Melville of a Department is aiming for State icato could be d Mount portrait donated to the I certification as an interdisciplinary major with "amre" commui -ta couEs museum's collection. Mount was a for next fall, according to Professor of form a *public a Oro- k mid-19th century American-artist who, Sociology and Communications Gladys reaserh" major. lived in Setauket. Iang. The failure to secure such Aodigto Long& aseerh KStorv on Paloa 2 certification, however, would not of thisp does, Mt m a A &W- A I preclude the University from offering "at upon the ei an least a concentration in interdisciplinary major. 'I see w of Getting Sleepy* communications," according to Lang. doing this even while we go lhogh tde The audience at the first Sunday The Communications Department was pocess, of getting certicatko for an Simpatico Series concert of this initiated three years ago in response to interdisciplinay miort" said . -

Come Enjoy the Music! 6 North Coast Voice Magazine | Northcoastvoice.Com • (440) 415-0999 | November 4 - 18, 2015

Live Music Weekends OPEN Sun-Thurs 12-6 ALL Winery Open daily at Noon YEAR! Year Round Visit us for your next Vacation or Get-Away! Four Rooms Complete with Private Hot Tubs 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfi eld, Ohio Three Rooms at $80 & Outdoor Patios 440.415.0661 One Suite at $120 www.bucciavineyard.com JOIN US FOR LIVE ENTERTAINMENT ALL Live Entertainment Fridays & Saturdays! WEEKEND! Appetizers & Full Entree www.debonne.com Menu See Back Cover See Back Cover For Full Info For Full Info www.grandrivercellars.com 2 North Coast Voice Magazine | northcoastvoice.com • (440) 415-0999 | November 4 - 18, 2015 Ohio Wines Trunk Program Ferrante Winery & Ristorante November 9, 7-8:30pm Join the Ferrante staff and Donniella Winchell of the Ohio Wine Producers for an evening of fun and education. The ‘Ohio Wines Trunk’ program is patterned after a very popular California Women for Winesense project. You will discover a bit about the history of our industry, understand why wine glasses’ shapes make a difference, learn why bottles are shaped and colored differently, realize why some wines have ‘real’ corks and others screwcaps, see an Fall/Winter Tasting Room hours: actual grapevine and understand why great wines are born in the vineyard and much much more. Closed Mondays Connect 534 This 90 minute program will conclude with a tasting of a selection of fi ne Ferrante wines. You’ll Open Tuesday-Sunday 11-6 was designed around take home recipes to match the wines you tasted and lots of other little ‘goodies.’ Please join JOIN US FOR LUNCH! creating and marketing us at 7 pm on November 9 for a fun fi lled and informative evening at their lovely Grand River Tuesday-Saturday 11-4pm Valley winery. -

Zappa-Bootlegs

MAJ du : 17/03/2008 Zappa-Bootlegs Lieux/Titres Concert du Qté Qualité Mount St Mary 19/05/1963 1 B == The Mothers Of Invention, Fall 1965 - Summer 1966 == FZ, Ray Collins, Elliot Ingber, Roy Estrada, Jimmy Carl Black Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, Ca (15 min) 24-25/06/1966 0,25 A- Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, CA (13,35 minutes) 24/06/1966 B+ == The Mothers Of Invention == Dec 1967 - Nov 1968 FZ, Ray Collins (quit somewhere between Apr and Aug 3 1968), Roy Estrada, Jimmy Carl Black, Arthur Dyer Tripp III, Ian Underwood, Don Preston, Bunk Gardner, Motorhead Sherwood. Olympen, Lund, Sweden 02/10/1967 1 B+ Lumpy Gravy Instrumental Acetate xx-xx-67 1 B+/A- We're Only In It For The Money Demo xx-xx-67 1 A- Fifth Dimension, Ann Arbor, Mi 03/12/1967 1 A-/B+ ==>Pigs & Repugnance Rare Meat Divers 1 American Pageant - Nullis Pretii - 67-68 / Studio 67 & 68 1 A (Mothermania) non-censored version The Grande Ballroom, Detroit, Mi (Mr. Green Genes==>Little House) 10/04/1968 1 B 03/05/68 Family Dog (!), Denver/ Concertgebouw, Amsterdam / Grugahalle, Essen 20/10/68 1 ==>Caress Me 28/09/68 Electric Aunt Jemima - Family Dog, Denver xx/01/1968 1 Family Dog, Denver, co xx/02/1968 1 A-/A The Grande Ballroom, Detroit, Mi 10/04/1968 1 B Fillmore East, NYC, NY - Early Show 20/04/1968 1 B- Fillmore East, NYC, NY - Late Show 20/04/1968 2 C+ Family Dog, Denver, co 03/05/1968 1 A- The Ark, Boston, Ma 18/07/1968 1 A- ==> Live In Boston Wollman Rink, Central Park, NYC, NY (source 1) 03/08/1968 1 B+ Wollman Rink, Central Park, NYC, NY (source 2) 03/08/1968 -

Estta861990 12/01/2017 in the United States

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA861990 Filing date: 12/01/2017 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91231132 Party Plaintiff Dweezil Zappa Correspondence MARIA CRIMI SPETH Address JABURG & WILK PC 3200 NORTH CENTRAL AVE STE 2000 PHOENIX, AZ 85012 UNITED STATES Email: [email protected] Submission Other Motions/Papers Filer's Name Maria Crimi Speth Filer's email [email protected] Signature /mariacrimispeth/ Date 12/01/2017 Attachments Zappa Amended Notice of Opposition.pdf(42171 bytes ) UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Dweezil Zappa, ) ) Opposition No. 91231132 Opposer, ) ) Mark: ZAPPA v. ) Serial No. 86918908 ) International Class: 041 Trustees of the Zappa Family Trust, ) Filed: February 24, 2016 ) Published: July 12, 2016 Applicant ) ) ) AMENDED NOTICE OF OPPOSITION Pursuant to the Board’s Order mailed November 1, 2017 granting Opposer Dweezil Zappa (“Opposer”) leave to file and serve an amended notice of opposition, Opposer, an individual with an address of 101 West Elm, Suite 500, Conshohocken, PA 19428, submits the following Amended Notice of Opposition. Opposer believes he will be damaged by the registration of the above identified mark filed by The Trustees of the Zappa Family Trust Administrative Trust (“Applicant”), comprised of Ahmet Zappa, an individual, and Diva Zappa and individual (together, “Trustees”), with an address of 3940 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Suite 859, Studio City, CA 91604, and hereby opposes such registration. As grounds for the opposition, it is alleged that: 1. ZAPPA is the legal surname of Opposer and Trustees, all of whom are siblings. -

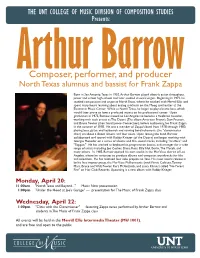

Composer, Performer, and Producer

THE UNT COLLEGE OF MUSIC DIVISION OF COMPOSITION STUDIES Presents: ArthurComposer, performer, Barrow and producer North Texas alumnus and bassist for Frank Zappa Born in San Antonio, Texas in 1952, Arthur Barrow played electric guitar throughout junior and senior high school and later studied classical organ. Beginning in 1971, he studied composition and organ at North Texas, where he worked with Merrill Ellis and spent many hours learning about analog synthesis on the Moog synthesizer at the Electronic Music Center. While at North Texas, he began to play electric bass, which would later prove to have a profound impact on his professional career. Upon graduation in 1975, Barrow moved to Los Angeles to become a freelance musician, working with such artists as The Doors (The album American Prayer), Don Preston, and Bruce Fowler (their band Loose Connection), before auditioning for Frank Zappa in the summer of 1978. He was a member of Zappa's band from 1978 through 1980, playing bass, guitar, and keyboards and running band rehearsals (the "clonemiester chair) on about a dozen albums and four tours. Upon leaving the band, Barrow collaborated and toured with Robby Krieger (of the Doors) and began working with Giorgio Moroder on a series of albums and film sound tracks, including "Scarface" and "Topgun." He has worked as keyboardist, programmer, bassist, and arranger for a wide range of artists including Joe Cocker, Diana Ross, Billy Idol, Berlin, The Motels, and many others. In 1985, Barrow opened his own studio in the Mar Vista district of Los Angeles, where he continues to produce albums and compose soundtracks for film and television.