3 Korea Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A PARTNER for CHANGE the Asia Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 a PARTNER Characterizing 60 Years of Continuous Operations of Any Organization Is an Ambitious Task

SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION IN KOREA SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION A PARTNER FOR CHANGE A PARTNER The AsiA Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 A PARTNER Characterizing 60 years of continuous operations of any organization is an ambitious task. Attempting to do so in a nation that has witnessed fundamental and dynamic change is even more challenging. The Asia Foundation is unique among FOR foreign private organizations in Korea in that it has maintained a presence here for more than 60 years, and, throughout, has responded to the tumultuous and vibrant times by adapting to Korea’s own transformation. The achievement of this balance, CHANGE adapting to changing needs and assisting in the preservation of Korean identity while simultaneously responding to regional and global trends, has made The Asia Foundation’s work in SIX DECADES of Korea singular. The AsiA Foundation David Steinberg, Korea Representative 1963-68, 1994-98 in Korea www.asiafoundation.org 서적-표지.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:42 서적152X225-2.indd 4 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 A PARTNER FOR CHANGE Six Decades of The Asia Foundation in Korea 1954–2017 Written by Cho Tong-jae Park Tae-jin Edward Reed Edited by Meredith Sumpter John Rieger © 2017 by The Asia Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission by The Asia Foundation. 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. -

U.S.-South Korea Relations

U.S.-South Korea Relations Mark E. Manyin, Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs Emma Chanlett-Avery Specialist in Asian Affairs Mary Beth D. Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation Brock R. Williams Analyst in International Trade and Finance Jonathan R. Corrado Research Associate May 23, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41481 U.S.-South Korea Relations Summary Overview South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea, or ROK) is one of the United States’ most important strategic and economic partners in Asia. Congressional interest in South Korea is driven by both security and trade interests. Since the early 1950s, the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty commits the United States to help South Korea defend itself. Approximately 28,500 U.S. troops are based in the ROK, which is included under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella.” Washington and Seoul cooperate in addressing the challenges posed by North Korea. The two countries’ economies are joined by the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). South Korea is the United States’ seventh-largest trading partner and the United States is South Korea’s second- largest trading partner. Between 2009 and the end of 2016, relations between the two countries arguably reached their most robust state in decades. Political changes in both countries in 2017, however, have generated uncertainty about the state of the relationship. Coordination of North Korea Policy Dealing with North Korea is the dominant strategic concern of the relationship. The Trump Administration appears to have raised North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs to a top U.S. -

U.S.-South Korea Relations

U.S.-South Korea Relations Mark E. Manyin, Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs Emma Chanlett-Avery Specialist in Asian Affairs Mary Beth Nikitin Analyst in Nonproliferation Mi Ae Taylor Research Associate in Asian Affairs December 8, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41481 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-South Korea Relations Summary Since late 2008, relations between the United States and South Korea (known officially as the Republic of Korea, or ROK) have been arguably at their best state in decades. By the middle of 2010, in the view of many in the Obama Administration, South Korea had emerged as the United States’ closest ally in East Asia. Of all the issues on the bilateral agenda, Congress has the most direct role to play in the proposed Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). Congressional approval is necessary for the agreement to go into effect. In early December 2010, the two sides announced they had agreed on modifications to the original agreement, which was signed in 2007. South Korea accepted a range of U.S. demands designed to help the U.S. auto industry and received some concessions in return. In the United States, the supplementary deal appears to have changed the minds of many groups and members of Congress who previously had opposed the FTA, which is now expected to be presented to the 112th Congress in 2011. If Congress approves the agreement, it would be the United States’ second largest FTA, after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). -

Korea-U.S. Relations: Issues for Congress

Order Code RL33567 Korea-U.S. Relations: Issues for Congress Updated July 25, 2008 Larry A. Niksch Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Korea-U.S. Relations: Issues for Congress Summary The United States has had a military alliance with South Korea and important interests in the Korean peninsula since the Korean War of 1950-53. Many U.S. interests relate to communist North Korea. Since the early 1990s, the issue of North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons has been the dominant U.S. policy concern. Experts in and out of the U.S. government believe that North Korea has produced at least six atomic bombs, and North Korea tested a nuclear device in October 2006. In 2007, a six party negotiation (between the United States, North Korea, China, South Korea, Japan, and Russia) produced agreements encompassing two North Korean and two U.S. obligations: disablement of North Korea’s Yongbyon nuclear installations, a North Korean declaration of nuclear programs, U.S. removal of North Korea from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism, and U.S. removal of North Korea from the sanctions provisions of the U.S. Trading with the Enemy Act. In June and July 2008, North Korea and the Bush Administration announced measures to implement fully the agreements by October 31, 2008. The Bush Administration has subordinated to the nuclear other North Korean activities that affect U.S. interests. North Korean exports of counterfeit U.S. currency and U.S. products produce upwards of $1 billion annually for the North Korean regime. -

Transformation of South Korean Politics: Implications for U.S.-Korea Relations

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES THE TRANSFORMATION OF SOUTH KOREAN POLITICS: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S.-KOREA RELATIONS Dr. Sook-Jong Lee 2003-2004 Korea Visiting Fellow September 2004 The Brookings Institution 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20036-2188 TEL: 202-797-6000 FAX: 202-797-6004 WWW.BROOKINGS.EDU 1 The speed and scope of South Korea’s political development in recent years have been as impressive as its economic development in previous decades. Since the transition to democracy occurred, with the belated arrival of political liberalization and a return to direct presidential elections in 1987, virtually all realms of Korean society have democratized. • In the political realm, under the Kim Dae-jung government, power shifted from the Kyongsang area in the southeast to Cholla in the southwest. This horizontal power shift is important for ending the political dominance of the Kyongsang area. Regional competition in the public policy-making process has become more democratic. • Both the Roh government and National Assembly have become more accountable for the public’s welfare and are better monitored by the Korean people. The power of public authority was often unchecked and misused in the past. Now Korean voters and civic representatives monitor whether public officials and assemblymen represent the public’s interest and observe their due responsibilities. • In terms of civilian-military relations, the government has become fully civilian, as the Korean military was completely depoliticized in the early 1990s. The history of former generals seizing the presidency was denounced and two former presidents, Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo, were convicted of crimes and sent to prison. -

The US in South Korea

THE U.S. IN SOUTH KOREA: ALLY OR EMPIRE? PERSPECTIVES IN GEOPOLITICS GRADE: 9-12 AUTHOR: Sharlyn Scott TOPIC/THEME: Social Studies TIME REQUIRED: Four to five 55-minute class periods BACKGROUND: This lesson examines different perspectives on the relationship between the U.S. and the Republic of Korea (R.O.K. – South Korea) historically and today. Is the United States military presence a benevolent force protecting both South Korean and American interests in East Asia? Or is the U.S. a domineering empire using the hard power of its military in South Korea solely to achieve its own geopolitical goals in the region and the world? Are there issues between the ROK and the U.S. that can be resolved for mutually beneficial results? An overview of the history of U.S. involvement in Korea since the end of World War II will be studied for context in examining these questions. In addition, current academic and newspaper articles as well as op-ed pieces by controversial yet reliable sources will offer insight into both American and South Korean perspectives. These perspectives will be analyzed as students grapple with important geopolitical questions involving the relationship between the U.S. and the R.O.K. CURRICULUM CONNECTION: This unit could be used with regional Geography class, World History, as well as American History as it relates to the Korean War and/or U.S. military expansion OBJECTIVES AND STANDARDS: The student will be able to: 1. Comprehend the historical relationship of the U.S. and the Korean Peninsula 2. Demonstrate both the U.S. -

Consolidation of Democracy in South Korea?

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Oriental Studies 21 CONSOLIDATION OF DEMOCRACY IN SOUTH KOREA? Gabriel Jonsson STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY 2014 © Gabriel Jonsson and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 2014 The publication is availabe for free on www.sub.su.se ISBN electronic version 978-91-87235-63-4 ISBN printed version 978-91-87235-64-1 ISSN 0585-3559 Department of Oriental Languages Stockholm University Stockholm 2014 Order AUS publications from : http://sub.su.se/online-shop.aspx Acknowledgements Firstly, I wish to extend my gratitude to those who have been kind enough to offer their assis- tance during the preparation of this book. This stimulating project would never have reached completion without two research visits to South Korea in 2010 and 2012. I therefore would like to acknowledge Torsten Söderbergs stiftelse [foundation] for providing research grants in 2010 and Magnus Bergvalls stiftelse [foundation] for providing research grants from 2011- 2012. A grant from Stiftelsen Lars Hiertas minne [The Lars Hierta Foundation] in 2013 is also greatly appreciated. In South Korea I wish to thank two former presidents of the Korea Institute for National Unification, PhD Suh Jae Jean and Kim Tae Woo, for allowing me to study at the institute. As a guest researcher, I benefited greatly from my affiliation with the institute in terms of colla- tion of relevant material and in establishing valuable contacts. The National Archive kindly provided the author photos of the five presidents who were in power from 1988-2013 and whose terms in office are the focus of this study. In addition, I wish to express my gratitude to anonymous readers of the manuscript. -

U.S.-South Korea Relations

U.S.-South Korea Relations (name redacted), Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs (name redacte d ) Specialist in Asian Affairs (name redacted) Specialist in Nonproliferation (name redacted) Analyst in Asian Affairs (name redacted) Analyst in International Trade and Finance March 28, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R41481 U.S.-South Korea Relations Summary Overview South Korea (known officially as the Republic of Korea, or ROK) is one of the United States’ most important strategic and economic partners in Asia, and since 2009 relations between the two countries arguably have been at their most robust state in decades. Several factors drive congressional interest in South Korea-related issues. First, the United States and South Korea have been military allies since the early 1950s. The United States is committed to helping South Korea defend itself, particularly against any aggression from North Korea. Approximately 28,500 U.S. troops are based in the ROK and South Korea is included under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella.” Second, Washington and Seoul cooperate in addressing the challenges posed by North Korea. Third, the two countries’ economies are closely entwined and are joined by the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). South Korea is the United States’ seventh-largest trading partner and the United States is South Korea’s second-largest trading partner. South Korea has repeatedly expressed interest in and consulted with the United States on possibly joining the U.S.- led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement, which has been signed, though not yet ratified by the current 12 participants. -

Living in Seoul

Living in Seoul 2015 Living in Seoul English Edition Living in Seoul Guide for Living in Seoul English Edition SEOUL GLOBAL CENTER | Tel_ 82-2-2075-4180 Fax_ 82-2-723-3205 http://global.seoul.go.kr English Edition contents Immigration 08 Visa 09 Stay 14 Foreign Registration 16 Overseas Koreans 18 Re-entry Permission 19 Departure 20 Q&A Transportation Accommodation 22 Using Public Transportation 38 Types of Accommodation 22 Subway 40 Types of Lease Contracts 25 Intra-city Buses 43 Real Estate Agents 27 Taxis 45 International Districts 29 Transit Cards 48 Purchase Procedures for Foreigners 30 Express Buses 49 Making the Move 31 Trains & Planes 51 Electricity 34 Q&A 51 Gas 52 Water Service 53 Q&A Garbage Disposal Communication Education Driving 56 Preparations for Garbage Collection & Banking 106 Education System 132 Driving in Seoul 57 General Waste 106 Educational Options 137 Penalty Points for Traffic Violations 57 Food Waste 66 Communication Facilities 107 Preschools 138 Penalty Points from Traffic Accidents 58 Recycling 71 Postal Services 108 Foreign Schools 139 Purchasing a Vehicle 59 Large Waste Matter 75 Telephone Services 114 Korean Language Education 144 Resident Prioritized Parking System 61 Recycling Centers and Flea Markets 78 Banking 116 Libraries & Book Stores 144 Rental Cars 63 Q&A 82 Q&A 119 Q&A 145 Motorcycles 146 Traffic Accidents 147 Q&A Employment Medical Services 86 Scope of Activities and Employment for Foreigners in Korea 122 Korean Medical System 86 Employment Procedures by Visa Status 123 Medical Services for Foreigners -

Informational Materials

Received by NSD/F ARA Registration Unit 02/08/2019 3:26:53 PM Nadine SIQCl!l'.l'.I From: Nadine Slocum Sent: Thursday, February 7, 2019 9:51 AM To: Lou, Theresa Cc: Hendrixson-White, Jennifer, Vinoda Basnayake Subject RE: Following up re: Korean delegation Attachments: 7. CV _Kim Kwari Young.pd!; 1S.CV "Kim Jong Dae.pdf, 14. CV "Park Joo Hyun.pdf, 13. CV_Baek Seung Joo.pd!; 12. CV_Chin Young.pdf; 11. CV_Choung Byoung Gug.pdf; 10. CV_Kim Jae Kyung.pd!; 9. CV_Lee Soo Hyuck.pdf, 8. CV_Kang Seok-ho.pdf; 6. CV_Na Kyung Won.pd!; 5. CV_Hong Young Pyo.pdf; 4. CV_Lee Jeong Mi.pd!; 3. CV_Chung Dong Young.pdf; 2. CV_Lee Hae-Chan.pdf, 1. CV_Korean National Assembly Delegation Feb.pdf, Bio - Moon Hee-Sang.pd! ' Hi Theresa, . Attached are the requested bias. Best, Nadine Slocum 202.689.2875 -----Original Message---- From: Vinoda Basnayake Sent: Wednesday, February 6, 2019 6:15 PM To: Lou, Theresa <[email protected]> Cc:· Hendrixson-White, Jennifer <[email protected]>; Nadine Slocum <[email protected]> Subject: Re: Following up re: Korean delegation Copied Nadine from our offioe who can help with this. Than.ks so much for your patience. Sent from my iPhone ! > On Feb 6, 2019, at 6:02 PM, Lou, Theresa·<[email protected]> wrote: > > Hello Vinoda, > > Thank you for this. Are there short bios for the members of the delegation, particularly the speaker? Those wciuld be much easil;!r for u_s to incorporate. Please let me know if there are questions. -

Selected Shelter List in South Korea

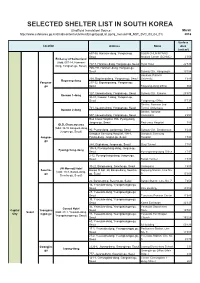

SELECTED SHELTER LIST IN SOUTH KOREA (Unofficial translation/ Source : March http://www.safekorea.go.kr/dmtd/contents/civil/est/EmgnEqupList.jsp?q_menuid=M_NST_SVC_03_04_01) 2016 Surface Location Address Name Area SOON CHUN HYANG Medical Center, (unit:m²) 657-58, Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, SOON CHUN HYANG Seoul Medical Center (SCHMC) 2'056 Embassy of Switzerland (Add: 657-14, Hannam- 747-7, Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Hyatt Hotel 22'539 dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul) 726-494, Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Subway Stn. Hangangjin 10'794 Hankook Politech 238, Bogwang-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul University 1'643 Bogwang-dong Yongsan- 217-32, Bigwang-dong, Yongsan-gu, gu Seoul Bogwang-dong Office 660 127, Itaewon-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Subway Stn. Itaewon 25'572 Itaewon 1-dong 34-87, Itaewon 1-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Yongsan-gu Office 17'737 Shelter, Namsan 2nd 721, Itaewon-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Tunnel Underpass 439 Itaewon 2-dong Shelter, Itaewon 507, Itaewon-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Underpass 2'294 Red Cross Hospital, 956, Pyung-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Red cross Hospital 789 OLD_Chancery area (Add: 32-10 Songwol-dong, 90, Pyung-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Subway Stn. Seodaemun 9'244 Jongno-gu, Seoul) Gangbuk Samsung Hospital, 108-1, Gangbuk Samsung Jongno- Pyung-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Hospital 1'598 gu 244, Gugi-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Gugi Tunnel 1'781 186-9, Pyeongchang-dong, Jongno-gu, Pyeongchang-dong Seoul Pyeongchang-dong Office 1'797 2-12, Pyeongchang-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Bukak Tunnel 1'838 30-22, Banpo-dong, Seocho-gu, Seoul Underpass 1'400 JW Marriott Hotel Seocho- Banpo Xi Apt, 20, Banpo-dong, Seocho- Sapyung Station, Line No. -

Seoul Domestic Policy and the Korean-American Alliance

Seoul Domestic Policy and the Korean-American Alliance B.C. Koh March 1999 1 2 About the Author B.C. Koh is professor of political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago. A native of Seoul, he was educated at Seoul National University (LL.B.) and Cornell University (Ph.D.). He has previously taught at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Seoul National Univer- sity (as a Fulbright lecturer), and Temple University Japan (as a visiting professor). He is author of Japan’s Administrative Elite (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989; paper ed. 1991), The Foreign Policy Systems of North and South Korea (University of California Press, 1984), and other works. 3 4 Seoul Domestic Politics and the Korean-American Alliance B.C. Koh Introduction While domestic politics helps to shape foreign policy, the two do not necessarily covary. That is to say, fundamental change in the former may not always trigger corresponding change in the latter. This is especially true of an alliance relationship, for a shared perception of an external threat that helps to sustain such a relationship is frequently unaffected by domestic political change. The developments on the Korean peninsula during the past decade exemplify these obser- vations. Notwithstanding breathtaking changes in South Korea’s domestic politics, the per- ceived threat emanating from North Korea has not abated, leaving the alliance between the Republic of Korea and the United States intact. The emergence of the nuclear crisis in the early 1990s, coupled with the frequency with which the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) precipitates provocative incidents vis-à-vis the Republic of Korea (ROK), has actually enhanced the importance of the Seoul–Washington alliance.