Noma Affected Children from Niger Have Distinct Oral Microbial Communities Based on High-Throughput Sequencing of 16S Rrna Gene Fragments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eelgrass Sediment Microbiome As a Nitrous Oxide Sink in Brackish Lake Akkeshi, Japan

Microbes Environ. Vol. 34, No. 1, 13-22, 2019 https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/jsme2 doi:10.1264/jsme2.ME18103 Eelgrass Sediment Microbiome as a Nitrous Oxide Sink in Brackish Lake Akkeshi, Japan TATSUNORI NAKAGAWA1*, YUKI TSUCHIYA1, SHINGO UEDA1, MANABU FUKUI2, and REIJI TAKAHASHI1 1College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, 1866 Kameino, Fujisawa, 252–0880, Japan; and 2Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University, Kita-19, Nishi-8, Kita-ku, Sapporo, 060–0819, Japan (Received July 16, 2018—Accepted October 22, 2018—Published online December 1, 2018) Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a powerful greenhouse gas; however, limited information is currently available on the microbiomes involved in its sink and source in seagrass meadow sediments. Using laboratory incubations, a quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of N2O reductase (nosZ) and ammonia monooxygenase subunit A (amoA) genes, and a metagenome analysis based on the nosZ gene, we investigated the abundance of N2O-reducing microorganisms and ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes as well as the community compositions of N2O-reducing microorganisms in in situ and cultivated sediments in the non-eelgrass and eelgrass zones of Lake Akkeshi, Japan. Laboratory incubations showed that N2O was reduced by eelgrass sediments and emitted by non-eelgrass sediments. qPCR analyses revealed that the abundance of nosZ gene clade II in both sediments before and after the incubation as higher in the eelgrass zone than in the non-eelgrass zone. In contrast, the abundance of ammonia-oxidizing archaeal amoA genes increased after incubations in the non-eelgrass zone only. Metagenome analyses of nosZ genes revealed that the lineages Dechloromonas-Magnetospirillum-Thiocapsa and Bacteroidetes (Flavobacteriia) within nosZ gene clade II were the main populations in the N2O-reducing microbiome in the in situ sediments of eelgrass zones. -

Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Marine Bacterial and Archaeal Communities in Surface Waters Off the Northern Antarctic Peninsula

Spatiotemporal dynamics of marine bacterial and archaeal communities in surface waters off the northern Antarctic Peninsula Camila N. Signori, Vivian H. Pellizari, Alex Enrich Prast and Stefan M. Sievert The self-archived postprint version of this journal article is available at Linköping University Institutional Repository (DiVA): http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-149885 N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original publication. Signori, C. N., Pellizari, V. H., Enrich Prast, A., Sievert, S. M., (2018), Spatiotemporal dynamics of marine bacterial and archaeal communities in surface waters off the northern Antarctic Peninsula, Deep-sea research. Part II, Topical studies in oceanography, 149, 150-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.12.017 Original publication available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.12.017 Copyright: Elsevier http://www.elsevier.com/ Spatiotemporal dynamics of marine bacterial and archaeal communities in surface waters off the northern Antarctic Peninsula Camila N. Signori1*, Vivian H. Pellizari1, Alex Enrich-Prast2,3, Stefan M. Sievert4* 1 Departamento de Oceanografia Biológica, Instituto Oceanográfico, Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Praça do Oceanográfico, 191. CEP: 05508-900 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 2 Department of Thematic Studies - Environmental Change, Linköping University. 581 83 Linköping, Sweden 3 Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Av. Carlos Chagas Filho, 373. CEP: 21941-902. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 4 Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). 266 Woods Hole Road, Woods Hole, MA 02543, United States. *Corresponding authors: Camila Negrão Signori Address: Departamento de Oceanografia Biológica, Instituto Oceanográfico, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. -

High Quality Permanent Draft Genome Sequence of Chryseobacterium Bovis DSM 19482T, Isolated from Raw Cow Milk

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title High quality permanent draft genome sequence of Chryseobacterium bovis DSM 19482T, isolated from raw cow milk. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4b48v7v8 Journal Standards in genomic sciences, 12(1) ISSN 1944-3277 Authors Laviad-Shitrit, Sivan Göker, Markus Huntemann, Marcel et al. Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.1186/s40793-017-0242-6 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Laviad-Shitrit et al. Standards in Genomic Sciences (2017) 12:31 DOI 10.1186/s40793-017-0242-6 SHORT GENOME REPORT Open Access High quality permanent draft genome sequence of Chryseobacterium bovis DSM 19482T, isolated from raw cow milk Sivan Laviad-Shitrit1, Markus Göker2, Marcel Huntemann3, Alicia Clum3, Manoj Pillay3, Krishnaveni Palaniappan3, Neha Varghese3, Natalia Mikhailova3, Dimitrios Stamatis3, T. B. K. Reddy3, Chris Daum3, Nicole Shapiro3, Victor Markowitz3, Natalia Ivanova3, Tanja Woyke3, Hans-Peter Klenk4, Nikos C. Kyrpides3 and Malka Halpern1,5* Abstract Chryseobacterium bovis DSM 19482T (Hantsis-Zacharov et al., Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:1024-1028, 2008) is a Gram-negative, rod shaped, non-motile, facultative anaerobe, chemoorganotroph bacterium. C. bovis is a member of the Flavobacteriaceae, a family within the phylum Bacteroidetes. It was isolated when psychrotolerant bacterial communities in raw milk and their proteolytic and lipolytic traits were studied. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the draft genome sequence and annotation. The DNA G + C content is 38.19%. The chromosome length is 3,346,045 bp. It encodes 3236 proteins and 105 RNA genes. The C. bovis genome is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Type Strains, Phase I: the one thousand microbial genomes study. -

Xiexin Tang Improves the Symptom of Type 2 Diabetic Rats by Modulation of the Gut Microbiota

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Xiexin Tang improves the symptom of type 2 diabetic rats by modulation of the gut microbiota Received: 30 August 2017 Xiaoyan Wei, Jinhua Tao , Suwei Xiao, Shu Jiang, Erxin Shang, Zhenhua Zhu, Dawei Qian Accepted: 13 February 2018 & Jinao Duan Published: xx xx xxxx Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a chronic metabolic disease which severely impairs peoples’ quality of life, currently attracted worldwide concerns. There are growing evidences that gut microbiota can exert a great impact on the development of T2DM. Xiexin Tang (XXT), a traditional Chinese medicine prescription, has been clinically used to treat diabetes for thousands of years. However, few researches are investigated on the modulation of gut microbiota community by XXT which will be very helpful to unravel how it works. In this study, bacterial communities were analyzed based on high-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Results indicated that XXT could notably shape the gut microbiota. T2DM rats treated with XXT exhibited obvious changes in the composition of the gut microbiota, especially for some short chain fatty acids producing and anti-infammatory bacteria such as Adlercreutzia, Alloprevotella, Barnesiella, [Eubacterium] Ventriosum group, Blautia, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, Papillibacter and Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group. Additionally, XXT could also signifcantly ameliorate hyperglycemia, lipid metabolism dysfunction and infammation in T2DM rats. Moreover, the correlation analysis illustrated that the key microbiota had a close relationship with the T2DM related indexes. The results probably provided useful information for further investigation on its active mechanism and clinical application. T2DM, a chronic metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia as a result of insufcient insulin secretion, insulin action or both1, is estimated that its numbers in the adults will increase by 55% by 20352. -

Evaluation of a New High-Throughput Method for Identifying Quorum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography OPEN Evaluation of a new high-throughput SUBJECT AREAS: method for identifying quorum BACTERIA APPLIED MICROBIOLOGY quenching bacteria HIGH-THROUGHPUT SCREENING Kaihao Tang1, Yunhui Zhang1, Min Yu1, Xiaochong Shi1, Tom Coenye2, Peter Bossier3 & Xiao-Hua Zhang1 MICROBIOLOGY TECHNIQUES 1College of Marine Life Sciences, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China, 2Laboratory of Pharmaceutical 3 Received Microbiology, Ghent University, 9000 Gent, Belgium, Laboratory of Aquaculture & Artemia Reference Center, Ghent University, 29 April 2013 9000 Gent, Belgium. Accepted 25 September 2013 Quorum sensing (QS) is a population-dependent mechanism for bacteria to synchronize social behaviors such as secretion of virulence factors. The enzymatic interruption of QS, termed quorum quenching (QQ), Published has been suggested as a promising alternative anti-virulence approach. In order to efficiently identify QQ 14 September 2013 bacteria, we developed a simple, sensitive and high-throughput method based on the biosensor Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136. This method effectively eliminates false positives caused by inhibition of growth of biosensor A136 and alkaline hydrolysis of N-acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs), through normalization of b-galactosidase activities and addition of PIPES buffer, respectively. Our novel approach Correspondence and was successfully applied in identifying QQ bacteria among 366 strains and 25 QQ strains belonging to 14 requests for materials species were obtained. Further experiments revealed that the QQ strains differed widely in terms of the type should be addressed to of QQ enzyme, substrate specificity and heat resistance. The QQ bacteria identified could possibly be used to X.-H.Z. -

Supplementary Information for Microbial Electrochemical Systems Outperform Fixed-Bed Biofilters for Cleaning-Up Urban Wastewater

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2016 Supplementary information for Microbial Electrochemical Systems outperform fixed-bed biofilters for cleaning-up urban wastewater AUTHORS: Arantxa Aguirre-Sierraa, Tristano Bacchetti De Gregorisb, Antonio Berná, Juan José Salasc, Carlos Aragónc, Abraham Esteve-Núñezab* Fig.1S Total nitrogen (A), ammonia (B) and nitrate (C) influent and effluent average values of the coke and the gravel biofilters. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. Fig. 2S Influent and effluent COD (A) and BOD5 (B) average values of the hybrid biofilter and the hybrid polarized biofilter. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. Fig. 3S Redox potential measured in the coke and the gravel biofilters Fig. 4S Rarefaction curves calculated for each sample based on the OTU computations. Fig. 5S Correspondence analysis biplot of classes’ distribution from pyrosequencing analysis. Fig. 6S. Relative abundance of classes of the category ‘other’ at class level. Table 1S Influent pre-treated wastewater and effluents characteristics. Averages ± SD HRT (d) 4.0 3.4 1.7 0.8 0.5 Influent COD (mg L-1) 246 ± 114 330 ± 107 457 ± 92 318 ± 143 393 ± 101 -1 BOD5 (mg L ) 136 ± 86 235 ± 36 268 ± 81 176 ± 127 213 ± 112 TN (mg L-1) 45.0 ± 17.4 60.6 ± 7.5 57.7 ± 3.9 43.7 ± 16.5 54.8 ± 10.1 -1 NH4-N (mg L ) 32.7 ± 18.7 51.6 ± 6.5 49.0 ± 2.3 36.6 ± 15.9 47.0 ± 8.8 -1 NO3-N (mg L ) 2.3 ± 3.6 1.0 ± 1.6 0.8 ± 0.6 1.5 ± 2.0 0.9 ± 0.6 TP (mg -

Gut Microbiome Composition Remains Stable in Individuals with Diabetes-Related Early to Late Stage Chronic Kidney Disease

biomedicines Article Gut Microbiome Composition Remains Stable in Individuals with Diabetes-Related Early to Late Stage Chronic Kidney Disease Ashani Lecamwasam 1,2,3,*, Tiffanie M. Nelson 4, Leni Rivera 3, Elif I. Ekinci 2,5, Richard Saffery 1,6 and Karen M. Dwyer 3 1 Epigenetics Research, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] 2 Department of Endocrinology, Austin Health, VIC 3079, Australia; [email protected] 3 School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, VIC 3220, Australia; [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (K.M.D.) 4 Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, QLD 4222, Australia; [email protected] 5 Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia 6 Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +613-8341-6200; Fax: +613-9348-1391 Abstract: (1) Background: Individuals with diabetes and chronic kidney disease display gut dysbiosis when compared to healthy controls. However, it is unknown whether there is a change in dysbiosis across the stages of diabetic chronic kidney disease. We investigated a cross-sectional study of patients with early and late diabetes associated chronic kidney disease to identify possible microbial differences between these two groups and across each of the stages of diabetic chronic kidney disease. (2) Methods: This cross-sectional study recruited 95 adults. DNA extracted from collected stool samples were used for 16S rRNA sequencing to identify the bacterial community in the Citation: Lecamwasam, A.; Nelson, gut. (3) Results: The phylum Firmicutes was the most abundant and its mean relative abundance T.M.; Rivera, L.; Ekinci, E.I.; Saffery, was similar in the early and late chronic kidney disease group, 45.99 ± 0.58% and 49.39 ± 0.55%, R.; Dwyer, K.M. -

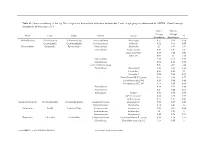

Genus Contributing to the Top 70% of Significant Dissimilarity of Bacteria Between Day 7 and 18 Age Groups As Determined by SIMPER

Table S1: Genus contributing to the top 70% of significant dissimilarity of bacteria between day 7 and 18 age groups as determined by SIMPER. Overall average dissimilarity between ages is 51%. Day 7 Day 18 Average Average Phyla Class Order Family Genus % Abundance Abundance Actinobacteria Actinobacteria Actinomycetales Actinomycetaceae Actinomyces 0.57 0.24 0.74 Coriobacteriia Coriobacteriales Coriobacteriaceae Collinsella 0.51 0.61 0.57 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides 2.1 1.63 1.03 Marinifilaceae Butyricimonas 0.82 0.81 0.9 Sanguibacteroides 0.08 0.42 0.59 CAG-873 0.01 1.1 1.68 Marinifilaceae 0.38 0.78 0.91 Marinifilaceae 0.78 1.04 0.97 p-2534-18B5 gut group 0.06 0.7 1.04 Prevotellaceae Alloprevotella 0.46 0.83 0.89 Prevotella 2 0.95 1.11 1.3 Prevotella 7 0.22 0.42 0.56 Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group 0.62 0.68 0.77 Prevotellaceae UCG-003 0.26 0.64 0.89 Prevotellaceae UCG-004 0.11 0.48 0.68 Prevotellaceae 0.64 0.52 0.89 Prevotellaceae 0.27 0.42 0.55 Rikenellaceae Alistipes 0.39 0.62 0.77 dgA-11 gut group 0.04 0.38 0.56 RC9 gut group 0.79 1.17 0.95 Epsilonbacteraeota Campylobacteria Campylobacterales Campylobacteraceae Campylobacter 0.58 0.83 0.97 Helicobacteraceae Helicobacter 0.12 0.41 0.6 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Enterococcaceae Enterococcus 0.36 0.31 0.64 Lactobacillaceae Lactobacillus 1.4 1.24 1 Streptococcaceae Streptococcus 0.82 0.58 0.53 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Christensenellaceae Christensenellaceae R-7 group 0.38 1.36 1.56 Clostridiaceae Clostridium sensu stricto 1 1.16 0.58 -

Ice-Nucleating Particles Impact the Severity of Precipitations in West Texas

Ice-nucleating particles impact the severity of precipitations in West Texas Hemanth S. K. Vepuri1,*, Cheyanne A. Rodriguez1, Dimitri G. Georgakopoulos4, Dustin Hume2, James Webb2, Greg D. Mayer3, and Naruki Hiranuma1,* 5 1Department of Life, Earth and Environmental Sciences, West Texas A&M University, Canyon, TX, USA 2Office of Information Technology, West Texas A&M University, Canyon, TX, USA 3Department of Environmental Toxicology, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA 4Department of Crop Science, Agricultural University of Athens, Athens, Greece 10 *Corresponding authors: [email protected] and [email protected] Supplemental Information 15 S1. Precipitation and Particulate Matter Properties S1.1 Precipitation Categorization In this study, we have segregated our precipitation samples into four different categories, such as (1) snows, (2) hails/thunderstorms, (3) long-lasted rains, and (4) weak rains. For this categorization, we have considered both our observation-based as well as the disdrometer-assigned National Weather Service (NWS) 20 code. Initially, the precipitation samples had been assigned one of the four categories based on our manual observation. In the next step, we have used each NWS code and its occurrence in each precipitation sample to finalize the precipitation category. During this step, a precipitation sample was categorized into snow, only when we identified a snow type NWS code (Snow: S-, S, S+ and/or Snow Grains: SG). Likewise, a precipitation sample was categorized into hail/thunderstorm, only when the cumulative sum of NWS codes for hail was 25 counted more than five times (i.e., A + SP ≥ 5; where A and SP are the codes for soft hail and hail, respectively). -

Role of Actinobacteria and Coriobacteriia in the Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine in an Inflammation Model of Depression

Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 176 (2019) 93–100 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharmbiochembeh Role of Actinobacteria and Coriobacteriia in the antidepressant effects of ketamine in an inflammation model of depression T Niannian Huanga,1, Dongyu Huaa,1, Gaofeng Zhana, Shan Lia, Bin Zhub, Riyue Jiangb, Ling Yangb, ⁎ ⁎ Jiangjiang Bia, Hui Xua, Kenji Hashimotoc, Ailin Luoa, , Chun Yanga, a Department of Anesthesiology, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, China b Department of Internal Medicine, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Changzhou 213003, China c Division of Clinical Neuroscience, Chiba University Center for Forensic Mental Health, Chiba 260-8670, Japan ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) antagonist, elicits rapid-acting and sustained anti- Ketamine depressant effects in treatment-resistant depressed patients. Accumulating evidence suggests that gut microbiota Depression via the gut-brain axis play a role in the pathogenesis of depression, thereby contributing to the antidepressant Lipopolysaccharide actions of certain compounds. Here we investigated the role of gut microbiota in the antidepressant effects of Gut microbiota ketamine in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation model of depression. Ketamine (10 mg/kg) sig- nificantly attenuated the increased immobility time in forced swimming test (FST), which was associated with the improvements in α-diversity, consisting of Shannon, Simpson and Chao 1 indices. In addition to α-diversity, β-diversity, such as principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) coupled with effect size measurements (LEfSe), showed a differential profile after ketamine treatment. -

Structural Basis of Mammalian Mucin Processing by the Human Gut O

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18696-y OPEN Structural basis of mammalian mucin processing by the human gut O-glycopeptidase OgpA from Akkermansia muciniphila ✉ ✉ Beatriz Trastoy 1,4, Andreas Naegeli2,4, Itxaso Anso 1,4, Jonathan Sjögren 2 & Marcelo E. Guerin 1,3 Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium commonly found in the human gut that promotes a beneficial effect on health, likely based on the regulation of mucus thickness 1234567890():,; and gut barrier integrity, but also on the modulation of the immune system. In this work, we focus in OgpA from A. muciniphila,anO-glycopeptidase that exclusively hydrolyzes the peptide bond N-terminal to serine or threonine residues substituted with an O-glycan. We determine the high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of the unliganded form of OgpA, the complex with the glycodrosocin O-glycopeptide substrate and its product, providing a comprehensive set of snapshots of the enzyme along the catalytic cycle. In combination with O-glycopeptide chemistry, enzyme kinetics, and computational methods we unveil the molecular mechanism of O-glycan recognition and specificity for OgpA. The data also con- tribute to understanding how A. muciniphila processes mucins in the gut, as well as analysis of post-translational O-glycosylation events in proteins. 1 Structural Biology Unit, Center for Cooperative Research in Biosciences (CIC bioGUNE), Basque Research and Technology Alliance (BRTA), Bizkaia Technology Park, Building 801A, 48160 Derio, Spain. 2 Genovis AB, Box 790, 22007 Lund, Sweden. 3 IKERBASQUE, Basque Foundation for Science, 48013 ✉ Bilbao, Spain. 4These authors contributed equally: Beatriz Trastoy, Andreas Naegeli, Itxaso Anso. -

Gut Microbiota Differs in Composition and Functionality Between Children

Diabetes Care Volume 41, November 2018 2385 Gut Microbiota Differs in Isabel Leiva-Gea,1 Lidia Sanchez-Alcoholado,´ 2 Composition and Functionality Beatriz Mart´ın-Tejedor,1 Daniel Castellano-Castillo,2,3 Between Children With Type 1 Isabel Moreno-Indias,2,3 Antonio Urda-Cardona,1 Diabetes and MODY2 and Healthy Francisco J. Tinahones,2,3 Jose´ Carlos Fernandez-Garc´ ´ıa,2,3 and Control Subjects: A Case-Control Mar´ıa Isabel Queipo-Ortuno~ 2,3 Study Diabetes Care 2018;41:2385–2395 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0253 OBJECTIVE Type 1 diabetes is associated with compositional differences in gut microbiota. To date, no microbiome studies have been performed in maturity-onset diabetes of the young 2 (MODY2), a monogenic cause of diabetes. Gut microbiota of type 1 diabetes, MODY2, and healthy control subjects was compared. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/COMPLICATIONS RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS This was a case-control study in 15 children with type 1 diabetes, 15 children with MODY2, and 13 healthy children. Metabolic control and potential factors mod- ifying gut microbiota were controlled. Microbiome composition was determined by 16S rRNA pyrosequencing. 1Pediatric Endocrinology, Hospital Materno- Infantil, Malaga,´ Spain RESULTS 2Clinical Management Unit of Endocrinology and Compared with healthy control subjects, type 1 diabetes was associated with a Nutrition, Laboratory of the Biomedical Research significantly lower microbiota diversity, a significantly higher relative abundance of Institute of Malaga,´ Virgen de la Victoria Uni- Bacteroides Ruminococcus Veillonella Blautia Streptococcus versityHospital,Universidad de Malaga,M´ alaga,´ , , , , and genera, and a Spain lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and 3Centro de Investigacion´ BiomedicaenRed(CIBER)´ Lachnospira.