Yellowstone National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 27 number 1 • 2010 Origins Founded in 1980, the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natural parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to he the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors ROLF DIA.MANT, President • Woodstock, Vermont STEPHANIE T(K)"1'1IMAN, Vice President • Seattle, Washington DAVID GKXW.R, Secretary * Three Rivers, California JOHN WAITHAKA, Treasurer * Ottawa, Ontario BRAD BARR • Woods Hole, Massachusetts MELIA LANE-KAMAHELE • Honolulu, Hawaii SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming BRENT A. MITCHELL • Ipswich, Massachusetts FRANK J. PRIZNAR • Gaithershnrg, Maryland JAN W. VAN WAGTENDONK • El Portal, California ROBERT A. WINFREE • Anchorage, Alaska Graduate Student Representative to the Board REBECCA E. STANFIELD MCCOWN • Burlington, Vermont Executive Office DAVID HARMON,Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • infoldgeorgewright.org • www.georgewright.org Tfie George Wright Forum REBECCA CONARD & DAVID HARMON, Editors © 2010 The George Wright Society, Inc. -

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

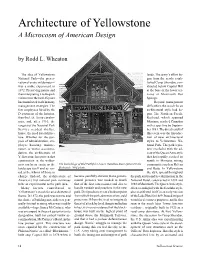

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge. -

HPC-Schedule-Print-Small.Pdf

Tuesday, September 30th, 2014 Travel to Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park 4:00 pm Hotel Check-In 5:00 pm Registration & Welcome Reception Old Faithful Lodge Recreation Hall Join old and new friends for a hearty round of hors d’ouevres and a warm welcome from conference partners. Wednesday, October 1st, 2014 7:30 am Registration/coffee at Old Faithful Lodge Recreation Hall 8:00 am Conference Orientation, Goals & Logistics Tom McGrath FAPT, Facilitator Chere Jiusto, Montana Preservation Alliance, Conference Coordinator 8:30 am National Park Service Rustic Architecture Laura Gates, NPS Superintendent Cane River Creole NHP, LA. Ms. Gates will present an overview of park rustic architecture including early hospitality structures and architect Robert Reamer’s structures, such as the Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone. The landscapes of our national parks contain iconic natural features that are indelibly imprinted in our minds: Old Faithful at Yellowstone; El Capitan and Half Dome at Yosemite; the General Sherman Tree at Sequoia National Park. These natural features frame our perception of the west and our treasured national parks. Synonymous with those iconic landscapes are the masterful buildings that grew out of those special places. Developed by the railroads, concessionaires, private interests, and the National Park Service, a type of architecture evolved during the late 19th and early 20th centuries that possessed strong harmony with the surrounding landscape and connections to cultural traditions. This architecture, most often categorized as “Rustic” served to enhance the visitor experience in these wild places. The architecture, too, frequently became as significant a part of the visitor experience as the national park itself. -

SHPO Preservation Plan 2016-2026 Size

HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Front cover images (left to right, top to bottom): Doll House, F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Downtown Buffalo. Photograph by Richard Collier Moulton barn on Mormon Row, Grand Teton National Park. Photograph by Richard Collier. Aladdin General Store. Photograph by Richard Collier. Wyoming State Capitol Building. Photograph by Richard Collier. Crooked Creek Stone Circle Site. Photograph by Danny Walker. Ezra Meeker marker on the Oregon Trail. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Green River Drift. Photograph by Jonita Sommers. Legend Rock Petroglyph Site. Photograph by Richard Collier. Ames Monument. Photograph by Richard Collier. Back cover images (left to right): Saint Stephen’s Mission Church. Photograph by Richard Collier. South Pass City. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Wyoming Theatre, Torrington. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Plan produced in house by sta at low cost. HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Matthew H. Mead, Governor Director, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Milward Simpson Administrator, Division of Cultural Resources Sara E. Needles State Historic Preservation Ocer Mary M. Hopkins Compiled and Edited by: Judy K. Wolf Chief, Planning and Historic Context Development Program Published by: e Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Wyoming State Historic Preservation Oce Barrett Building 2301 Central Avenue Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 City County Building (Casper - Natrona County), a Public Works Administration project. Photograph by Richard Collier. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................5 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................6 Letter from Governor Matthew H. -

408 1941 Boathouse (Lake)

Index 45th Parallel Pullout 33 Arch Park 29, 270, 326, 331 1926 Boathouse (Lake) 408 Arnica Bypass 1941 Boathouse (Lake) 408 See Natural Bridge Service Rd 1998 Concessions Management Arnica Creek 125, 135, 136, 202 Improvement Act 485 Artemisia Geyser 172, 435, 456 Artemisia Trail 172 A Arthur, Chester A. 401 Artist Paint Pots 209, 215 Abiathar Peak 57 Artist Point 93, 280, 283 Absaroka Mountain Range Ash, Jennie 309, 311, 355 58, 60, 108, 125, 127 Ashton (ID) 300 Administration Building 345 Aspen Dormitory 259, 354 Africa Lake 250 Aspen Turnouts 67 Albright, Horace Asta Spring 174 21, 175, 205, 259 270, 338 Astringent Creek 117 Albright Visitor Center 259, 338, 348 Avalanche Peak Trail 110 Altitude Sickness 7 Avenue A 41 Alum Creek 95, 97, 185 Avenue B American Bison Turnout 98 See Mammoth to Tower Jct American Eden Turnout 63 Avenue C See Officer’s Row Amfac 323, 445 See also Xanterra Avenue of Travel Turnout 204 Amfac Parks and Resorts See Amfac Amphitheater Creek 59 B Amphitheater Springs Thermal Area 238, 239 Bachelor Officer’s Quarters 259 Amphitheater Valley 72, 79 Back Basin 218, 221 Anderson, Ole 309, 311, 364 Bacon Rind Creek 264 Angel Terrace 299 Bacon Rind Creek Trail 264 Antelope Creek 78 Bannock Ford 40, 78 Antelope Creek Picnic Area 78 Bannock Indians 47 Antelope Creek Valley Bannock Indian Trail 39, 45, 47, 48 See Amphitheater Valley 242 Antler Peak 245 Barn’s Hole Road 196, 198, 311 Aphrodite Terrace 299 Baronette Peak 58 Apollinaris Spring 241 Baronette Ski Trail 58 Apollinaris Spring Picnic Area Baronett, John H. -

Montana a Guide to the Museums and National Historic Sites with French Interpretation

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1980 Montana A guide to the museums and national historic sites with French interpretation Mary Elizabeth Maclay The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maclay, Mary Elizabeth, "Montana A guide to the museums and national historic sites with French interpretation" (1980). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5078. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5078 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s . Any further r e p r in tin g of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR. Man sfield Library U n iv e r s it y of Montana Da t e : 1 9 8 0 MONTANA, A GUIDE TO THE MUSEUMS AND NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES, WITH FRENCH INTERPRETATION by Mary Elizabeth Blair Maclay B.A., Montana State University, 1951 Presented in partial fu lfillm e n t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Interdisciplinary Studies UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1980 Approved by: Chairman, Boardof Examiners Deem, Graduate Sctoo I 7 r t f * UMI Number: EP40542 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

National Park System Properties in the National Register of Historic Places

National Park System Properties in the National Register of Historic Places Prepared by Leslie H. Blythe, Historian FTS (202) 343-8150 January, 1994 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Cultural Resources Park Historic Architecture Division United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE P.O. Box 37127 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 H30(422) MAR 3 11994 Memorandum To: Regional Directors and Superintendents r From: Associate Director, Cultural Resources Subject: MPS Properties in the National Register of Historic Places Attached for your information is an updated list of properties within the National Park System listed in the National Register of Historic Places. National Historic Landmark status, documentation status, dates, and the National Register database reference number are included. This list reflects changes within 1993. Information for the sections Properties Determined Eligible by Keeper and Properties Determined Eligible by NPS and SHPO is not totally available in the Washington office. Any additional information for these sections or additions, corrections, and questions concerning this listing should be referred to Leslie Blythe, Park Historic Architecture Division, 202-343-8150. Attachment SYMBOLS KEY: Documentation needed. Documentation may need to be revised or updated. (•) Signifies property not owned by NPS. Signifies property only partially owned by NPS (including easements). ( + ) Signifies National Historic Landmark designation. The date immediately following the symbol is the date that the property was designated an NHL (Potomac Canal Historic District (+ 12/17/82) (79003038). Some properties designated NHLs after being listed will have two records in the NR database: one for the property as an historical unit of the NPS, the other for the property as an NHL. -

Federal Register / Vol. 48, No. 41 / Tuesday, March 1, 1983 / Notices 8621

Federal Register / Vol. 48, No. 41 / Tuesday, March 1, 1983 / Notices 8621 UNITED STATES INFORMATION 2. The authority to redelegate the VETERANS ADMINISTRATION AGENCY authority granted herein together with the power of further redelegation. Voluntary Service National Advisory [Delegation Order No. 83-6] Texts of all such advertisements, Committee; Renewal notices, and proposals shall be This is to give notice in accordance Delegation of Authority; To the submitted to the Office of General Associate Director for Management with the Federal Advisory Committee Counsel for review and approval prior Act (Pub. L. 92-463) of October 6,1972, Pursuant to the authority vested in me to publication. that the Veterans Administration as Director of the United States Notwithstanding any other provision Voluntary Service National Advisory Information Agency by Reorganization of this Order, the Director may at any Committee has been renewed by the Plan No. 2 of 1977, section 303 of Pub. L. time exercise any function or authority Administrator of Veterans Affairs for a 97-241, and section 302 of title 5, United delegated herein. two-year period beginning February 7, States Code, there is hereby delegated This Order is effective as of February 1983 through February 7,1985. 8,1983. to the Associate Director for Dated: February 15,1983. Management the following described Dated: February 16,1983. By direction of the Administrator. authority: Charles Z. Wick, Rosa Maria Fontanez, 1. The authority vested in the Director Director, United States Information Agency. by section 3702 of title 44, United States Committee Management Officer. [FR Doc. 83-5171 Filed 2-28-83; 8:45 am] Code, to authorize the publication of [FR Doc. -

Preserving Cultural Resources

PRESERVATION Yellowstone’s cultural resources tell the stories of people, shown here around 1910 near the Old Faithful Inn, and their connections to the park. The protection of these resources affects how the park is managed today. Preserving Cultural Resources Yellowstone National Park’s mission includes pre- have been in the area. Archeological evidence indi- serving and interpreting evidence of past human cates that people began traveling through and using activity through archeology and historic preservation; the area that was to become Yellowstone National features that are integral to how a group of people Park more than 11,000 years ago. Because the in- identifies itself (ethnographic resources); and places tensity of use varies through time as environmental associated with a significant event, activity, person conditions shift, archeological resources also provide or group of people that provide a sense of place a means for interdisciplinary investigations of past and identity (historic buildings, roads, and cultural climate and biotic change. landscapes). All of these materials and places tell the Many thermal areas contain evidence that early story of people in Yellowstone. Collectively, they are people camped there. At Obsidian Cliff, a National referred to as cultural resources. Historic Landmark, volcanic glass was quarried for the manufacture of tools and ceremonial artifacts Archeology that entered a trading network extending from Archeological resources are the primary—and often western Canada to the Midwest. These remnants -

Yellowstone Center for Resources

YELLOWSTONE CENTER FOR RESOURCES IAL Ana SPAT lysis s e N c SOURC r RE E A u T o U s e R R A L L R A e R s o U u T r L c e U s C I nformation R ES rt EARCH Suppo ANNUAL2002 REPORT FISCAL YEAR YELLOWSTONE CENTER FOR RESOURCES 2002 ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR (OCTOBER 1, 2001, TO SEPTEMBER 30, 2002) Yellowstone Center for Resources National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR–AR–2002 2003 Suggested citation: Yellowstone Center for Resources. 2003. Yellowstone Center for Resources Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2002. National Park Service, Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming, YCR–AR–2002. Photographs not otherwise marked are courtesy of the National Park Service. Front cover: clockwise from top right, a possible McKean component precontact site; J.E. Stuart’s “Old Faithful” oil painting; elk and a Druid pack wolf by Monty Sloan; Eastern Shoshone dancer by Sandra Nykerk; and center, peregrine falcon fledgling by Wayne Wolfersberger. Title page: wolf #113, alpha male of the Agate Creek pack, attacking a cow elk. Photo by anonymous donor. Back cover: Yellowstone cutthroat trout. ii Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................iv Part I. Resource Highlights ...............................................................................1 Part II. Cultural Resource Programs ................................................................7 Archeology.......................................................................................................8 Ethnography -

Yellowstone National Park Resources & Issues

PRESERVATION Yellowstone’s cultural resources tell the stories of people. Fort Yellowstone was constructed when the US Army administered the park. The protection of resources affects how the park is managed today. Preserving Cultural Resources Yellowstone National Park’s mission includes pre- have been in the area. Archeological evidence indi- serving and interpreting evidence of past human cates that people began traveling through and using activity through archeology and historic preservation; the area that was to become Yellowstone National features that are integral to how a group of people Park more than 11,000 years ago. Because the in- identifies itself (ethnographic resources); and places tensity of use varies through time as environmental associated with a significant event, activity, person conditions shift, archeological resources also provide or group of people that provide a sense of place a means for interdisciplinary investigations of past and identity (historic buildings, roads, and cultural climate and biotic change. landscapes). All of these materials and places tell the Many thermal areas contain evidence that early story of people in Yellowstone. Collectively, they are people camped there. At Obsidian Cliff, a National referred to as cultural resources. Historic Landmark, volcanic glass was quarried for the manufacture of tools and ceremonial artifacts Archeology that entered a trading network extending from Archeological resources are the primary—and often western Canada to the Midwest. These remnants of the only—source -

This Survey Was Financed in Part with Funds Granted to the Teton County Historic Preservation Board from the National Park Service, U.S

This survey was financed in part with funds granted to the Teton County Historic Preservation Board from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office administers these federal funds as part of Wyoming’s Certified Local Government program. This program received Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Dept. of the Interior. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1073, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Dept. of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, handicap, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission A.