On the Anatomy of Conus Tulipa, Linn., and Conus Textile, Linn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAST1986050004005.Pdf

BASTERIA, 50: 93-150, 1986 Alphabetical revision of the (sub)species in recent Conidae. 9. ebraeus to extraordinarius with the description of Conus elegans ramalhoi, nov. subspecies H.E. Coomans R.G. Moolenbeek& E. Wils Institute of Taxonomic Zoology (Zoological Museum) University of Amsterdam INTRODUCTION In this ninth part of the revision all names of recent Conus taxa beginning with the letter e are discussed. Amongst these are several nominal species of tent-cones with a C.of close-set lines, the shell a darker pattern consisting very giving appearance (e.g. C. C. The elisae, euetrios, eumitus). phenomenon was also mentioned for C. castaneo- fasciatus, C. cholmondeleyi and C. dactylosus in former issues. This occurs in populations where with normal also that consider them specimens a tent-pattern are found, so we as colour formae. The effect is known shells in which of white opposite too, areas are present, leaving 'islands' with the tent-pattern (e.g. C. bitleri, C. castrensis, C. concatenatus and C. episco- These colour formae. patus). are also art. Because of a change in the rules of the ICZN (3rd edition, 1985: 73-74), there has risen a disagreement about the concept of the "type series". In cases where a museum type-lot consists of more than one specimen, although the original author(s) did not indicate that more than one shell was used for the description, we will designate the single originally mentioned and/or figured specimen as the "lectotype". Never- theless a number of taxonomists will consider that "lectotype" as the holotype, and disregard the remaining shells in the lot as type material. -

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda)1

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 1 ALAN J. KOHN2 IN THECOURSE OF a comparative ecological currents are factors which could plausibly study of gastropod mollus ks of the genus effect the isolation necessary for geographic Conus in Hawaii (Ko hn, 1959), some 2,400 speciation . specimens of 25 species were examined. Un Of the 33 species of Conus considered in certainty ofthe correct names to be applied to this paper to be valid constituents of the some of these species prompted the taxo Hawaiian fauna, about 20 occur in shallow nomic study reported here. Many workers water on marine benches and coral reefs and have contributed to the systematics of the in bays. Of these, only one species, C. ab genus Conus; nevertheless, both nomencla breviatusReeve, is considered to be endemic to torial and biological questions have persisted the Hawaiian archipelago . Less is known of concerning the correct names of a number of the species more characteristic of deeper water species that occur in the Hawaiian archi habitats. Some, known at present only from pelago, here considered to extend from Kure dredging? about the Hawaiian Islands, may (Ocean) Island (28.25° N. , 178.26° W.) to the in the future prove to occur elsewhere as island of Hawaii (20.00° N. , 155.30° W.). well, when adequate sampling methods are extended to other parts of the Indo-West FAUNAL AFFINITY Pacific region. As is characteristic of the marine fauna of ECOLOGY the Hawaiian Islands, the affinities of Conus are with the Indo-Pacific center of distribu Since the ecology of Conus has been dis tion . -

Silent Auction Previe

1 North Carolina Shell Club Silent Auction II 17 September 2021 Western Park Community Center Cedar Point, North Carolina Silent Auction Co-Chairs Bill Bennight & Susan O’Connor Special Silent Auction Catalogs I & II Dora Zimmerman (I) & John Timmerman (II) This is the second of two silent auctions North Carolina Shell Club is holding since the Covid-19 pandemic started. During the pandemic the club continued to receive donations of shells. Shells Featured in the auctions were generously donated to North Carolina Shell Club by Mique Pinkerton, the family of Admiral Jerrold Michael, Vicky Wall, Ed Shuller, Jeanette Tysor, Doug & Nancy Wolfe, and the Bosch family. North Carolina Shell Club members worked countless hours to accurately confirm identities. Collections sometimes arrive with labels and shells mixed. Scientific classifications change. Some classifications are found only in older references. Original labels are included with the shells where possible. Classification herein reflect the latest reference to WoRMS. Some Details There will be two silent auctions on September 17. There are some very cool shells in this and the first auctions. Some are shells not often available in the recent marketplace. There are “classics” and the out of the ordinary. There is something here for everyone. Pg. 4 Pg. 9 Pg. 7 Pg. 8 Pg.11 Pg. 4 Bid well and often North Carolina Shell Club Silent Auction II, 17 September 2021 2 Delphinula Collection Common Delphinula Angaria delphinus (Linnaeus, 1758) (3 shells) formerly incisa (Reeve, 1843) top row Roe’s -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

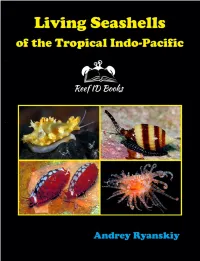

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos. -

Auckland Shell Club Auction Lot List - 24 October 2015 Albany Hall

Auckland Shell Club Auction Lot List - 24 October 2015 Albany Hall. Setup from 9am. Viewing from 10am. Auction starts at noon. Lot Type Reserve 1 WW Many SMALL CYPRAEIDAE including the rare Rosaria caputdraconis from Easter Is. Mauritian scurra from Somalia, Cypraea eburnea white from from, New Caledonia, Cypraea chinensis from Solomon Is Lyncina sulcidentata from Hawaii and heaps more. 2 WW Many CONIDAE including rare Conus queenslandis (not perfect!) Conus teramachii, beautiful Conus trigonis, Conus ammiralis, all from Australia, Conus aulicus, Conus circumcisus, Conus gubernator, Conus generalis, Conus bullatus, Conus distans, and many more. 3 WW BIVALVES: Many specials including Large Pearl Oyster Pinctada margaritifera, Chlamys sowerbyi, Glycymeris gigantea, Macrocallista nimbosa, Pecten glaber, Amusiium pleuronectes, Pecten pullium, Zygochlamys delicatula, and heaps more. 4 WW VOLUTIDAE: Rare Teramachia johnsoni, Rare Cymbiolacca thatcheri, Livonia roadnightae, Zidona dufresnei, Lyria kurodai, Cymbiola rutila, Cymbium olia, Pulchra woolacottae, Cymbiola pulchra peristicta, Athleta studeri, Amoria undulata, Cymbiola nivosa. 5 WW MIXTURE Rare Campanile symbolium, Livonia roadnightae, Chlamys australis, Distorsio anus, Bulluta bullata, Penion maximus, Matra incompta, Conus imperialis, Ancilla glabrata, Strombus aurisdianae, Fusinus brasiliensis, Columbarium harrisae, Mauritia mauritana, and heaps and heaps more! 6 WW CYPRAEIDAE: 12 stunning shells including Trona stercoraria, Cypraea cervus, Makuritia eglantrine f. grisouridens, Cypraea -

Radular Morphology of Conus (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Conidae) from India

Molluscan Research 27(3): 111–122 ISSN 1323-5818 http://www.mapress.com/mr/ Magnolia Press Radular morphology of Conus (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Conidae) from India J. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, 1, 3 S. ANTONY FERNANDO, 1 B. A. CHALKE, 2 K. S. KRISHNAN. 2, 3* 1.Centre of Advanced Study in Marine Biology, Annamalai University, Parangipettai-608 502, Cuddalore, Tamilnadu, India. 2.Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Colaba, Mumbai-400 005, India. 3.National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR, Old Bellary Road, Bangalore-560 065, India.* Corresponding author E-mail: (K. S. Krishnan): [email protected]. Abstract Radular morphologies of 22 species of the genus Conus from Indian coastal waters were analyzed by optical and scanning elec- tron microscopy. Although the majority of species in the present study are vermivorous, all three feeding modes known to occur in the genus are represented. Specific radular-tooth structures consistently define feeding modes. Species showing simi- lar feeding modes also show fine differences in radular structures. We propose that these structures will be of value in species identification in cases of ambiguity in other characteristics. Examination of eight discrete radular-tooth components has allowed us to classify the studied species of Conus into three groups. We see much greater inter-specific differences amongst vermivorous than amongst molluscivorous and piscivorous species. We have used these differences to provide a formula for species identification. The radular teeth of Conus araneosus, C. augur, C. bayani, C. biliosus, C. hyaena, C. lentiginosus, C. loroisii, and C. malacanus are illustrated for the first time. In a few cases our study has also enabled the correction of some erroneous descriptions in the literature. -

Conopeptide Production Through Biosustainable Snail Farming A

Conopeptide Production through Biosustainable Snail Farming A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MOLECULAR BIOSCIENCES AND BIOENGINEERING DECEMBER 2012 By Jeffrey W. Milisen Thesis Committee: Jon-Paul Bingham (Chairperson) Harry Ako Cynthia Hunter Keywords: Conus striatus venom variability Student: Jeffrey W. Milisen Student ID#: 1702-1176 Degree: MS Field: Molecular Biosciences and Bioengineering Graduation Date: December 2012 Title: Conopeptide Production through Biosustainable Snail Farming We certify that we have read this Thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a Thesis for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biosciences and Bioengineering. Thesis Committee: Names Signatures Jon-Paul Bingham (Chair) ___________________________ Harry Ako ___________________________ Cynthia Hunter ___________________________ ii Acknowledgements The author would like to take a moment to appreciate a notable few out of the army of supporters who came out during this arduously long scholastic process without whom this work would never have been. First and foremost, a “thank you” is owed to the USDA TSTAR program whose funds kept the snails alive and solvents flowing through the RP-HPLC. Likewise, the infrastructure, teachings and financial support from the University of Hawai‘i and more specifically the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources provided a fertile environment conducive to cutting edge science. Through the 3 years over which this study took place, I found myself indebted to two distinct groups of students from Dr. Bingham’s lab. Those who worked primarily in the biochemical laboratory saved countless weekend RP-HPLC runs from disaster through due diligence while patiently schooling me on my deficiencies in biochemical processes and techniques. -

Zoologische Mededelingen Uitgegeven Door Het

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 53 no. 13 25 oktober 1978 THE MARINE MOLLUSCAN ASSEMBLAGES OF PORT SUDAN, RED SEA by M. MASTALLER Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Lehrstuhl für Spez. Zoologie Bochum, West-Germany With one text-figure and one table ABSTRACT This study summarizes field observations and collections of the molluscan fauna of the coastal and offshore reefs in the area of Port Sudan, Central Red Sea. In spite of the fact that some families of this group were described from several areas of the Red Sea, there exists only little information on the entire faunal composition of this region. 282 species of Amphineura, Gastropoda, and Bivalvia, collected and studied in nine localities are listed according to their habitats. Moreover, descriptions of the prominent members of typical molluscan assemblages are given for 13 habitats and microhabitats which differ in their morphological structures and in their hydrographic and physiographic conditions. Emphasis is placed on further studies on the trophic interactions within certain habitats. INTRODUCTION Although there is a considerable number of taxonomie literature on some molluscan families in the Indo-West-Padfic (Abbott, i960; Burgess, 1970; Cernohorsky, 1967; Habe, 1964; Kira, 1962; Powell, 1964; Rosewater, 1965), there is comparatively scarce information for the Red Sea. After the exten• sive surveys and descriptions of Issel, 1869, Hall & Standen, 1907, Jickeli, 1874, Shopland, 1902, and Sturany, 1901, 1903, in more recent times only a few studies were published on the entire faunal composition of molluscs in this region. Most of these publications deal with certain families, sometimes they also give information about their zoogeographical distribution in the Red Sea: Thus the cypraeids seem to yield the best information on their occurrence throughout the region (Foin, 1972; Mienis, 1971b; O'Malley, 1971; Schilder, 1965). -

The Cone Collector

THE CONE COLLECTOR #7 - July 2008 THE CONE COLLECTOR Note From Editor the Editor António Monteiro You are now in possession of issue number 7 of Th e Cone Col- lector, which is actually our eighth issue! If you follow this Layout newsletter from the beginning, you will know that this ap- André Poremski parent numerical paradox – which can appear particularly bizarre since your Editor is in fact a Maths’ teacher – result from the fact that we started with an experimental issue, Contributors which was identifi ed as issue #0. John Abba Once again we have tried to put together an interesting col- Luigi Bozzetti lection of articles, with something for everyone – you may Jim Cootes actually fi nd a couple of rather surprising subjects inside…– Bill Fenzan from beginners to the Cone world (if not even to the shell world) to advanced collectors. Mike Filmer Richard Goldberg Th anks are due to all the authors who took the time to write those articles and send them along. Surely nothing could be Brian Hammond done without them! And the sheer variety of subjects cov- Kelly McCarthy ered will hopefully encourage others to contribute too. Don Moody May I say that I am especially satisfi ed with the “Who’s Who Philippe Quiquandon in Cones” column? I have always felt that shell collecting is Jon Singleton not only about shells, it is also about making friends. Being in touch with people from all over the world who share our Manuel Jiménez Tenorio interests is for me a major reward of collecting. -

Shell's Field Guide C.20.1 150 FB.Pdf

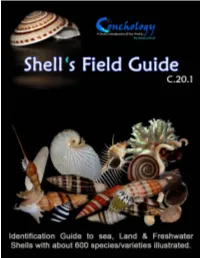

1 C.20.1 Human beings have an innate connection and fascination with the ocean & wildlife, but still we know more about the moon than our Oceans. so it’s a our effort to introduce a small part of second largest phylum “Mollusca”, with illustration of about 600 species / verities Which will quit useful for those, who are passionate and involved with exploring shells. This database made from our personal collection made by us in last 15 years. Also we have introduce website “www.conchology.co.in” where one can find more introduction related to our col- lection, general knowledge of sea life & phylum “Mollusca”. Mehul D. Patel & Hiral M. Patel At.Talodh, Near Water Tank Po.Bilimora - 396321 Dist - Navsari, Gujarat, India [email protected] www.conchology.co.in 2 Table of Contents Hints to Understand illustration 4 Reference Books 5 Mollusca Classification Details 6 Hypothetical view of Gastropoda & Bivalvia 7 Habitat 8 Shell collecting tips 9 Shell Identification Plates 12 Habitat : Sea Class : Bivalvia 12 Class : Cephalopoda 30 Class : Gastropoda 31 Class : Polyplacophora 147 Class : Scaphopoda 147 Habitat : Land Class : Gastropoda 148 Habitat :Freshwater Class : Bivalvia 157 Class : Gastropoda 158 3 Hints to Understand illustration Scientific Name Author Common Name Reference Book Page Serial No. No. 5 as Details shown Average Size Species No. For Internal Ref. Habitat : Sea Image of species From personal Land collection (Not in Scale) Freshwater Page No.8 4 Reference Books Book Name Short Format Used Example Book Front Look p-Plate No.-Species Indian Seashells, by Dr.Apte p-29-16 No. -

The Cone Collector N°24A

THE CONE COLLECTOR #24A April 2014 THE Note from CONE the Editor COLLECTOR Dear friends, Editor In our last issue we included the first part of a larger work by António Monteiro David Touitou and other authors, under the generic title Cone Snails Regional Iconographies. This first part was about the Layout Cones from Mauritius and Mayotte. André Poremski Contributors Unfortunately, after publication, David spotted a number of Eric Le Court de Billot mistakes that needed to be corrected. Matthias Deuss David Touitou It would be rather awkward to make the appropriate changes Norbert Verneau in the text of TCC # 24, since having two different versions of that issue would probably cause some confusion. So, we de- cided prepare a Supplement with the corrected articles, which we have labeled TCC # 24A. I do apologize to the authors for all the confusion involuntarily created. We try our best but sometimes we are so eager to pub- lish a new issue that we just have our guard down for some moments – enough to allow errors to creep in! In the meantime, issue # 25 is already well advanced and will hopefully be published in the near future. I am happy to inform that David’s articles will be continued with new geographical areas being covered. Surely something to look forward to! Until then, very best wishes, António Monteiro On the Cover Conus episcopatus from Maritius. Photo by Eric Le Court de Bilot Page 41 THE CONE COLLECTOR ISSUE #24A Conidae from Mauritius Eric Le Court de Billot & David Touitou Thanks for their help to : Felix Lorenz, Loïc Limpalaer, Mauritius offers, like other Indian Ocean localities, Giancarlo Paganelli, Paul Kersten, Antonio Monteiro, surprising variations of Conus (Cylinder) textile, Manuel Tenorio, Bruno Mathé, John K Tucker. -

The Biodiversity of Marine Gastropods of Thailand in the Late Decade

Malaysian Journal of Science 32 (SCS Sp Issue) : 47-64 (2013) The Biodiversity of Marine Gastropods of Thailand in the Late Decade. Kitithorn Sanpanich1*and Teerapong Duangdee2 1Institute of Marine Science, Burapha University, Tambon Saensook, Amphur Moengchonburi, Chonburi, 20131 Thailand. 2Department of Marine Science, Faculty of Fisheries, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, 10900 Thailand. *[email protected] (Corresponding author) ABSTRACT This study is mainly based on the collection of marine gastropods along the east coast of the Gulf of Thailand which had been carried out along the coastline in 55 sites from the province of Chonburi to Trad during April 2005 – December 2009. As many habitats as possible were examined at each sites from sandy beaches, muddy sand, rocky shore, and coral reefs. A total of 306 species of gastropods were collected and had been classifi ed in53families 116genera.The most widespread species were Planaxis sulcatus (Planaxidae) and Polinices mammilla (Naticidae) found in 37 sites, followed by Echinolittorina malaccana (Littorinidae) in 35 sites. The highest diversity was 187 species in Trat whereas Koh Mark had the most abundance in this area. The lowest diversity was in Chanthaburi, 88 species, whereas Koh Nomsoa was the most abundant site.The diversity of gastropods in Chonburi was 152 species, whereas Koh Samaesarn and Koh Juang were the most abundant site. 137 species had been found in Rayong and Koh Munnai was the most abundant site. The data from this study had been compared with the resent studies in the late decade from the west coast of the Gulf of Thailand and Andaman Sea.The total gastropods in the late decade were 454 species 205 genera 69 families.