Jersey 1940-45 a Brief History of the Occupation Doug Ford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulatory Update Jersey - Summer 2018

Regulatory Update Jersey - Summer 2018 In a bid to persuade you that there is news out there that doesn't involve Brexit, Trump or football, here is our latest round up of regulatory developments in Jersey! As you will see from the short summaries in this edition of our update, the last quarter has seen a real mix of legislative change, court judgments and new guidance and consultation from the JFSC, all of which should be of interest to the regulated community in Jersey. In the rush for the publishing deadline, however, there are inevitably a few developments that arise at the last minute but are still worthy of a passing mention here. The JFSC has published a guidance note on the application process for issuers of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), which is intended to 'illustrate [the JFSC's] commitment to fintech developments' in a manner that is 'permissive and promotes innovation and new enterprise', whilst also maintaining safeguards to protect investors. The JFSC has also now published a further update in relation to Phase II of the Risk Data Collection Exercise, setting out a new timetable for data collection. Most regulated businesses can relax for the rest of the summer, until the end of August, by which time they will receive further details on data collection over the following months, but those who are supervised for AML purposes only, as well as FSB managed entities and certain specific standalone activities, will receive notice by end of July for reporting by end of September. Finally, the JFSC has also published feedback on its themed visits in relation to revised Registry requirements on beneficial owners and controllers and, following the Francis case that we mention below, a new guidance note on integrity and competence. -

GIN Members' Newsletter

JUNE 2020 GIN Members' Newsletter ISSUE NO. 3 An update on key issues for in-house Counsel in Guernsey as at 8 June 2020 1 New Bailiff and Deputy Bailiff We couldn't really start off this newsletter in any other way than to celebrate the changing of Guernsey's judicial guard on 12 and 14 May 2020. With the retirement of Sir Richard Collas as Bailiff, Richard McMahon became the Bailiff at a ceremony beamed to the community from a sparsely occupied Royal Court using Microsoft Teams. However we are sure that the new Bailiff will forgive us if we trumpet the appointment of our own Jessica Roland as the island's first female Deputy Bailiff two days later on 14 May 2020. Jessica joined Ozannes (as it then was) in 1998, becoming a partner in 2005 and Managing Partner from 2013 until taking on her new role. She is well known for her expertise in employment law but, as was highlighted in her admission ceremony, she is a rarity at the Guernsey Bar in having such a wide spread of work experience - ideal for a judge. We wish her all the best in her new job but will of course miss her singing in the corridors….. 2 Business as Usual at the Royal Court With the arrival of Phase 4 of release from lockdown, the Royal Court is now operating close to normality:- • The Greffe and Court building are open from 9am – 4pm. • The HM Sergeant and HM Sheriff team are back at full service; • The backlog of criminal and civil litigation has started to be cleared - a Judge and three Jurats can sit and still observe social distancing – and parties who need hearings are getting them relatively quickly; • General Petty Debts will recommence on 11 June 2020 and Petty Debt Hearings started on 1 June 2020. -

Specific Flag Days

Specific flag days Country/Territory/Continent Date Details Afghanistan August 19 Independence day, 1919. Albania November 28 Independence day, 1912. Anniversary of the death of Manuel Belgrano, who created the Argentina June 20 current flag. Aruba March 18 Flag day. Adoption of the national flag on March 18, 1976. Australian National Flag Day commemorates the first flying of Australia September 3 the Australian National Flag in 1901. State Flag Day, was officially established in 2009, for the Azerbaijan November 9 commemoration of the adoption of the Flag of Azerbaijan on November 9, 1918. Åland Last Sunday of April Commemorates adoption of the Åland flag Flag Day in Bolivia. Commemorates of the creation of the first August 17 Bolivia national flag. Brazil November 19 Flag Day in Brazil; adopted in 1889 Canada National Flag of Canada Day commemorates adoption of the February 15 Canadian flag, Feb. 15, 1965. January 21[4][5] Québec Flag Day (French: Jour du Drapeau) commemorates Quebec the first flying of the flag of Quebec, January 21, 1948. July 20 Declaration of Independence (1810) (Celebrated as National Colombia August 7 Day); Battle of Boyaca (1819) Dia di Bandera ("Day of the Flag"). Adoption of the national July 2 Curaçao flag on 2 July 1984. Anniversary of the Battle of Valdemar in 1219 in Lyndanisse, Estonia, where according to legend, the ("Dannebrog") fell Denmark June 15 from the sky. It is also the anniversary of the return of North Slesvig in 1920 to Denmark following the post-World War I plebiscite. "Day of the National Flag" ("Dia de la Bandera Nacional"). -

Channel Islands Telegraph Company

A History of the Telegraph in Jersey 1858 – 1940 Graeme Marett MIET This edition July 2009 1 The Telegraph System. Jersey, being only a relatively small outpost of the British Empire, was fortunate in having one of the earliest submarine telegraph systems. Indeed the installation of the first UK-Channel Islands link was made concurrently with the first attempted (but abortive) trans-Atlantic cable in 18581. There was some British Government interest in the installation of such a cable, since the uncertain relationship with the French over the past century had led to the fortification of the Channel Islands as a measure to protect Channel shipping lanes. The islands were substantially fortified and garrisons were maintained well into the early part of the twentieth century. Indeed, the Admiralty had installed an Optical Telegraph between the islands during the Napoleonic wars using a bespoke system developed by Mulgrave2. Optical signalling using a two arm semaphore was carried out between Alderney and Sark and Sark to Jersey and Guernsey. The main islands of Jersey and Guernsey had a network of costal stations. This system was abandoned by the military at the end of the conflict in 1814, but the States of Jersey were loaned the stations and continued to use the system for several years thereafter for commercial shipping. The optical semaphore links between La Moye, Noimont and St Helier continued until a telegraph line was installed in April 1887 between La Moye and St Helier. There is still some evidence of this telegraph network at Telegraph Bay in Alderney, where a fine granite tower is preserved, and the Signalling Point at La Moye, Jersey which survives as a private residence. -

Sotira Rousou (From Akanthou)

¶∞ƒ√π∫π∞∫∏ ¶POO¢EYTIKH EºHMEPI¢A ™THN Y¶HPE™IA TH™ KY¶PIAKH™ ¶APOIKIA™ ¶∂ª¶Δ∏ 31 π√À§π√À 2014 ● XPONO™ 39Ô˜ ● AÚÈıÌfi˜ ʇÏÏÔ˘ 2063 ● PRICE: 75 pence ∞∞ÁÁÔÔÚÚ¿¿˙˙ÔÔ˘˘ÌÌ Î΢˘ÚÚÈÈ··Îο¿ ÚÚÔÔ˚˚fifiÓÓÙÙ·· ΔΔ··ÍÍÈȉ‰Â‡‡ÔÔ˘˘ÌÌ ÛÛÙÙËËÓÓ ∫∫‡‡ÚÚÔÔ ™™ÙÙËËÚÚ››˙˙ÔÔ˘˘ÌÌ ÙÙÔÔÓÓ ÙÙfifiÔÔ ÌÌ··˜˜ ‰È·‚¿ÛÙ ۋÌÂÚ·: «∞Ú·ÎÙÈο» ÛÙÔÓ ¤ÏÂÁ¯Ô ∞ƒ£ƒ∞ Ù˘ ΔÚ¿Â˙·˜ ∫‡ÚÔ˘! §∂À∫ø™π∞ – ∞ÓÙ·fiÎÚÈÛË Î˘ÚÈ·Îfi Ï·fi Ì ÙË Û‡ÌʈÓÔ ÛÎÔÈÎÒÓ ÎÂÊ·Ï·›ˆÓ, Ù· ıÔ˜ ÙˆÓ ˙ËÌÈÒÓ Ô˘ ˘¤ÛÙË- ¢ÚÒ. ∏ ΔÔ˘ÚΛ·, ¶∂Δƒ√™ ¶∞™π∞™ ÁÓÒÌË ÙÔ˘ ¶ÚÔ¤‰ÚÔ˘ Ù˘ ∫˘- ÔÔ›· Ì¿ÏÈÛÙ· ÂÍÂȉÈ·ÔÓÙ·È Û·Ó Ù· ÚˆÛÈο Û˘ÌʤÚÔÓÙ· √ È‰Ú˘Ù‹˜ Î·È Úfi‰ÚÔ˜ Úȷ΋˜ ¢ËÌÔÎÚ·Ù›·˜. ª›· ÛÙË ‰È·¯Â›ÚÈÛË ÂÓ˘fiıËÎˆÓ Î˘Ú›ˆ˜ ·fi ÙÔ ÎÔ‡ÚÂÌ· ÙˆÓ Ù˘ ÂÙ·ÈÚ›·˜, ∞ÌÂÚÈηÓfi˜ ‰È- Ë ÂÚÈÔ¯‹ ËÓ ·ÓËÛ˘¯›· ÙÔ˘ ∞∫∂§ ÔÚ›· Ô˘ ÂÚȤϷ‚ ÙÔ ÎÏ›- ‰·Ó›ˆÓ, ÂÚÈÏ·Ì‚·ÓÔÌ¤ÓˆÓ Î·Ù·ı¤ÛˆÓ, ÔÊ›ÏÔ˘Ó Ó· ÛÂηÙÔÌÌ˘ÚÈÔ‡¯Ô˜ Wilbur Î·È Ë ·ÙÚ›‰· Ì·˜ ÁÈ· ÙË Û˘ÌÌÂÙÔ¯‹ ÛÙËÓ ÛÈÌÔ Ù˘ ‰Â‡ÙÂÚ˘ ÌÂÁ·Ï‡ÙÂ- Î·È ÙˆÓ ÛÙÂÁ·ÛÙÈÎÒÓ», ·Ó¤ÊÂ- ·Ó·˙ËÙ‹ÛÔ˘Ó ÈÛÔÚÚԛ˜ ÔÈ Ross, Ô ÔÔ›Ô˜ ÛÙÔ ·ÚÂÏıfiÓ ·Ó·ÎÂÊ·Ï·ÈÔÔ›ËÛË Ù˘ ● ™ÂÏ. 8 Δ Ú˘ ÙÚ¿Â˙·˜ ÙÔ˘ ÙfiÔ˘, ÚÂ Î·È ÚfiÛıÂÛ fiÙÈ «¢ÂÓ ıÂ- Ôԛ˜ Ó· ‰È·ÛÊ·Ï›˙Ô˘Ó ÙË Â›¯Â ¯·Ú·ÎÙËÚÈÛÙ› ˆ˜ «Î·ÏÔ- ΔÚ¿Â˙·˜ ∫‡ÚÔ˘ «·Ú·ÎÙÈ- ÎÔ‡ÚÂÌ· ηٷı¤ÛÂˆÓ ‰ÈÛÂη- ‰È·¯ÚÔÓÈ΋ ·ÚÔ˘Û›· ÙˆÓ Úˆ- ÓÙ˘Ì¤ÓÔ ·Ú·ÎÙÈÎfi», ʤÚÂÙ·È ¶∞ƒ√π∫π∞ ÎÒÓ» Î·È ¿ÎÚˆ˜ ÎÂÚ‰ÔÛÎÔÈ- ÙÔÌÌ˘Ú›ˆÓ ¢ÚÒ, ·Î‡ÚˆÛË ÛÈÎÒÓ ÎÂÊ·Ï·›ˆÓ ÛÙËÓ ∫‡- Ó· ¤¯ÂÈ ÏÔ‡ÛÈ· ‰Ú¿ÛË ÛÙËÓ ÎÒÓ ÎÂÊ·Ï·›ˆÓ Ô˘ ÂÍÂȉÈ·- ·ÍÈÔÁÚ¿ÊˆÓ Î·È ·Ï·ÈÒÓ ÌÂ- ÚÔ». -

Channel Islands from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Channel Islands From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the British Crown dependencies. For the islands off Southern California, see Channel Islands of California. For the Navigation French Channel Islands, see Chausey. Main page The Channel Islands (Norman: Îles d'la Manche, French: Îles Anglo-Normandes or Îles de la Contents Channel Islands Manche) are an archipelago of British Crown Dependencies in the English Channel, off the Featured content French coast of Normandy. They include two separate bailiwicks: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and Current events the Bailiwick of Jersey. They are considered the remnants of the Duchy of Normandy, and are Random article not part of the United Kingdom.[1] They have a total population of about 168,000 and their Donate to Wikipedia respective capitals, Saint Peter Port and Saint Helier, have populations of 16,488 and 28,310. The total area of the islands is 194 km². Interaction The Bailiwicks have been administered separately since the late 13th century; common Help institutions are the exception rather than the rule. The two Bailiwicks have no common laws, no About Wikipedia common elections, and no common representative body (although their politicians consult Community portal regularly). Recent changes Contents Contact page 1 Geography 2 History Toolbox 2.1 Prehistory The Channel Islands, located between the south What links here 2.2 From the Iron Age coast of the United Kingdom and northern France. Related changes 2.3 -

GG Spring 2017.Pdf

Grouville GazetteGazette An independent glimpse of life in our parish Spring 2017 Volume 15 Issue 1 Printed on paper from sustainable resources. Shed damage could threaten Battle entry Grouville’s Battle of Flowers entry is feeling the effects of work finished by then, I am sure that the community in the damage storm Angus did to the parish shed back in Grouville will come together – like it does whenever we November. need something – to make sure that our parish float is compeleted on time.’ A tree from a field opposite the shed, on La Rue de Grouville, crashed into the building, destroying part of The parish Battle team have managed to get another the roof and causing damage to the structure at one end. source of electricity into the building to help them with Initial estimates suggest the cost of the repair could be the work they need to do in the early stages and hairstail- as much as £30,000, although the parish’s insurance will ing is taking place at the Constable’s home at Les Pres be able to cover that. Manor in the meantime. However, due to various reports and structural surveys, Mr Le Maistre added: ‘There’s a great community spirit in theG repair work has been held back for some weeks and, Grouville, so I am confident we will get it sorted one way atG the time of printing, was awaiting building control to or another.’ pass the plans for the repair work due to the change in build- ing methods since its original construction in the 1980s. -

The Battle of the Strong

The Battle Of The Strong Gilbert Parker The Battle Of The Strong Table of Contents The Battle Of The Strong.........................................................................................................................................1 Gilbert Parker.................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................4 PROEM..........................................................................................................................................................4 Volume 1.....................................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER I...................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III..............................................................................................................................................11 CHAPTER IV..............................................................................................................................................13 -

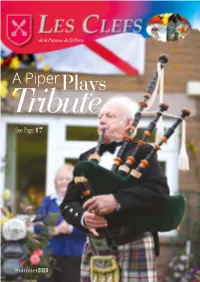

A Piperplays Tribute

de la Paroisse de St Pierre A PiperPlays Tribute See Page 17 Summer2020 With up to 20% discount when taking out both motor and home insurance policies, you can drive away happy www.islands.je 835 200 [email protected] Home / Travel / Motor / Marine / Business Regulated by the Jersey Financial Services Commission under the Financial Services (Jersey) Law. 1998 for General Insurance Mediation Business (Reference: GIMB 0046). Jersey Registered Company Number: 2589. A Member of the NFU Mutual Group of Companies Featured ARTICLES WelcomeAs editor, time seems to go by rather too quickly for me; one minute it’s the middle of winter and the next it’s the middle of spring and the start of a dreadful pandemic! Along the way, as the quarters roll by, 6 Bee friendly I’m always on the lookout for items to include in the next magazine, and sometimes that search can be a struggle, finding things that will interest, and hopefully amuse readers, is not always very easy. 8 Were you a school athlete in the mid ‘50s? These last few months though, have been particularly strange. I thought, with the Liberation, there would be plenty of articles to 9 Fast moving village idiots include in this edition. As it turned out things were a little muted to say the least. A fantastic public celebration had been planned, which would have included a Street Party, an exhibition of Occupation 10 The tale of a talking cars memorabilia, a flower festival at the church and the annual Parish Ambassador competition but sadly all these were cancelled, and a wealth of potential magazine material denied in an instant. -

The Battle of the Strong (A Romance of Two Kingdoms), Volume 6

The Battle Of The Strong (A Romance of Two Kingdoms), Volume 6. Gilbert Parker The Project Gutenberg EBook The Battle Of The Strong, by G. Parker, v6 #62 in our series by Gilbert Parker Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **EBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These EBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers***** Title: The Battle Of The Strong [A Romance of Two Kingdoms], Volume 6. Author: Gilbert Parker Release Date: August, 2004 [EBook #6235] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 10, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BATTLE OF THE STRONG, PARKER, V6 *** This eBook was produced by David Widger <[email protected]> Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. -

List of Legislatures by Country 1 List of Legislatures by Country

List of legislatures by country 1 List of legislatures by country Legislature This series is part of the Politics series • Legislature • Legislatures by country • Parliament • Member of Parliament • Parliamentary group • Parliamentary group leader • Congress • Congressperson • Unicameralism • Multicameralism • Bicameralism • Tricameralism (historical) • Tetracameralism (historical) • Chambers of parliament • Upper house (Senate) • Lower house • Parliamentary system • City council • Councillor Politics Portal · [1] This is a list of legislatures by country, whether parliamentary or congressional, that act as a plenary general assembly of representatives with the power to legislate. In the lists below all entities included in the list of countries are included. Names of legislatures The legislatures are listed with their names in English and the name in the (most-used) native language of the country (or the official name in the second-most used native language in cases where English is the majority "native" language). The names of the legislatures differ from country to country. The most used name seems to be National Assembly, but Parliament and Congress are often used too. The name Parliament is in some cases even used when in political science the legislature would be considered a congress. The upper house of the legislature is often named the Senate. In some cases, countries use very traditional names. In Germanic countries variations Thing (e.g. Folketinget) are used. A thing or ting was the governing assembly in Germanic societies, made up of the free men of the community and presided by lawspeakers. A variant is the use of the word Tag or Dag (e.g. Bundestag), used because things were held at daylight and often lasted all day. -

A N N U a L R E P O

2019 Fulfilling the obligations of the Authority under article 44 of the Data Protection Authority (Jersey) Law 2018 and the Information Commissioner ANNUAL REPORT under article 43 of the Freedom of Information (Jersey) Law 2011. R.49/2020 CONTENTS 03 2019 HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS 25 ANNUAL REPORT OF FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACTIVITIES 05 THE JERSEY DATA PROTECTION AUTHORITY’S ROLE, Benefits of Effective Freedom of Information VISION, MISSION, PROMISE AND 2019 STRATEGIC AIMS The Freedom of Information (Jersey) Law 2011 2019 Operational Performance and Appeals Significant 2019 Decision Notices 07 INTRODUCTION View from the Chair View from the Commissioner 29 PUBLIC AWARENESS, ENGAGEMENT AND EDUCATION 11 ORGANISATION The JDPA and the States Assembly The JOIC Events About the Jersey Office of the Information Commissioner Education National/International Liaison 2019 13 GOVERNANCE, ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY The Data Protection Authority 35 COMMUNICATIONS AND OPERATIONS Delegation of Powers Brand Development Authority Structure Relocation Authority Meetings Website and App Authority Members Remuneration Social Media Accountability Arrangements Media and the JOIC The JOIC Team Data Protection Week - January 2019 Awards and Recognition 17 THE NEW REGISTRATION AND FEES MODEL 43 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY 19 SUMMARY OF 2019 DATA PROTECTION ACTIVITIES Corporate Social Responsibility Benefits of Effective Data Protection 2019 Operational Performance Enforcement 45 FINANCIAL INFORMATION Breach Reporting 1 • Jersey Office of the Information Commissioner