His Domestic Life, However, D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pot Lid Out, Wally Bird in Owners Epiris in 2016

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp 7 1 -2 0 2 1 9 1 ISSUE 2507 | antiquestradegazette.com | 4 September 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 S E E R 50years D koopman rare art V A I R N T antiques trade G T H E KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY 12 Dover Street, W1S 4LL [email protected] | www.koopman.art | +44 (0)20 7242 7624 Robert Brooks: the boss who built the Bonhams brand by Alex Capon in 2010. He always looked up to his father, naming the new lecture theatre at Bonhams Former chairman of New Bond Street in his honour Bonhams Robert Brooks in 2005. has died aged 64 after a He opposed guarantees Among the highlights two-year battle with (although did occasionally use of the Alan Blakeman cancer. them later on) and challenged collection to be sold Having started his own Sotheby’s and Christie’s to by BBR Auctions on classic car saleroom, Brooks follow Bonhams’ example of September 11 is this Auctioneers, at the age of 33, introducing separate client shop display pot lid. he bought Bonhams 11 years accounts for vendors’ funds. Blakeman was pictured with later before merging it with Never lacking a competitive it on the cover of the programme Phillips in 2001. He streak, Brooks had left school produced for the first UK Summer subsequently expanded the as a teenager to briefly become National fair in 1985 (above). -

This Northern England City Called York Or Jorvik, During the Viking Age, Is Quite Medieval in Terms of Cultural History

History of York, England This northern England city called York or Jorvik, during the Viking age, is quite medieval in terms of cultural history. York is a tourist‐oriented city with its Roman and Viking heritage, 13th century walls, Gothic cathedrals, railroad station, museum‐gardens an unusual dinner served in a pub, and shopping areas in the Fossgate, Coppergate and Piccadilly area of the city. Brief History of York According to <historyofyork.org> (an extensive historical source), York's history began with the Romans founding the city in 71AD with the Ninth Legion comprising 5,000 men who marched into the area and set up camp. York, then was called, "Eboracum." After the Romans abandoned Britain in 400AD, York became known as "Sub Roman" between the period of 400 to 600AD. Described as an "elusive epoch," this was due to little known facts about that period. It was also a time when Germanic peoples, Anglo‐Saxons, were settling the area. Some archaeologists believe it had to do with devasting floods or unsettled habitation, due to a loss of being a trading center then. The rivers Ouse and Foss flow through York. <historyofyork.org> Christianity was re‐established during the Anglo‐Saxon period and the settlement of York was called "Eofonwic." It is believed that it was a commercial center tied to Lundenwic (London) and Gipeswic (Ipswich). Manufacturing associated with iron, lead, copper, wool, leather and bone were found. Roman roads made travel to and from York easier. <historyofyork.org> In 866AD, the Vikings attacked. Not all parts of England were captured, but York was. -

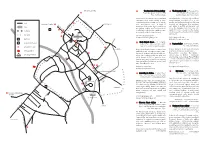

Artmap2mrch Copy

Bils & Rye 25 miles 9 The New School House Gallery - 10 The Fossgate Social - 25 Fossgate,York. 17 Peasholme Green, York. YO1 7PW. YO1 9TA. Mon-Fri 8.30am-12am, Tues - Sat 10am-5pm. Sat 9am-12am, Sun 10am-11pm. Paula Jackson and Robert Teed co-founded An independent coee bar with craft beer, lo The New School House Gallery in 2009. award winning speciality coee, a cute rd m Together they have curated over 30 exhibi- garden and a relaxed atmosphere. Hosting road 45 a te yo Kunsthuis 15 miles 18 a r huntington tions and projects across a range of monthly art exhibitions, from paintings b g s o y w o ll a and prints to grati, photography and th i lk disciplines and media. Since establishing river a g m the gallery, Jackson and Teed have been more; the Fossgate Social runs open mic P 1 3 nights for music, comedy, and the spoken footway developing a collaborative artistic practice 2 to complement their curatorial work. word. All events are free to perform, exhibit s t l and attend. bar walls e a schoolhousegallery.co.uk 4 o york minster n [email protected] thefossgatesocial.com a r P parking d [email protected] e s t p i 6 a l p g Kiosk Project Space - 41 Fossgate, et 11 i visitor information er m g a 12 Rogues Atelier - 28a Fossgate, Y019TA. r York. YO1 9TF. Tues - Sun 8am - 5pm. te 7 a a te d Open by appointment. eg o Open on occasion for evening events. -

York Cemetery – Accidental Deaths – Victorian (Jan 2019)

Approx. time Friends of York Cemetery 1½ hours + Accidental Deaths – Victorian Section One of a series of trails to enhance your enjoyment of the Cemetery Registered Charity Best enjoyed: All Year Round No. 701091 INTRODUCTION This Trail will take you around the 8 acres of the Road traffic accidents and industrial accidents have Victorian Section of the Cemetery, visiting 22 graves always been with us and also feature in this Trail. of people who were accidentally killed either at work It is not possible to give an accurate figure of the or pursuing their leisure activities. numbers of people accidentally killed and buried in With its two rivers, the Ouse and the Foss, the term York Cemetery. 'Accidentally Drowned' makes a regular appearance in This Trail is based on those monuments that include the 'Cause of Death' entry in the Cemetery Burial the word 'accident' or 'killed' in their inscription. It Registers. Significantly, most drowning accidents must be remembered that only the better off families resulted from children falling through ice during the could afford the cost of a memorial. Consequently, Winter months or whilst at play in the Summer. It the deaths of many poor people are not memorialised, should be remembered that, in Victorian times, rivers although 'local knowledge' enables some of them to provided free entertainment at a time of true poverty. be included. Railways and railway safety were very much in their The Cemetery Burial Registers provide only limited infancy during the Victorian era and many people lost assistance in determining the number of such deaths. -

Breeding Rams – Twilight Tups 1

BREEDING RAMS – TWILIGHT TUPS 1 - Tuesday 27 September The top price ram at Gisburn auction marts multi breed ram sale on Tuesday 27 September was £900 from eighteen year old Seth Blakey, Bolton by Bowland, Clitheroe, Lancashire. Mr Blakey was delighted with his trade, having just graduated from Bishop Burton College with a National Diploma in Agriculture. His second prize Texel shearling ram was out of a homebred ewe and sired by Dutch Texel, which sold to Simon Duerden, Blacko, Lancashire. Next best was the first prize Texel shearling ram from Sam Mellor, Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire, which sold for £600 to Steven Entwistle, Darwen, Blackburn, Lancashire. Suffolk breeding and dairy farmer Mark Gornall, Clitheroe, Lancashire sold his Suffolk Shearling for £600 to JM Fisher, Belmont, Bolton, Lancashire. Alan Harker, Long Preston, Settle, North Yorkshire was in the money with his pen of Texel shearlings which sold topped at £590 and averaged £535. Frank Cleary, Tockholes, Darwen, Lancashire sold £590 for his Beltex crossed Charollais lamb. Another Lancashire farmer to achieve over the £500 plus mark was Joe Holden, Edgworth, Bolton, Lancashire with his Texel shearling ram which sold for £590 to Simon Foster, Calton, Skipton, North Yorkshire. M Williams & Sons journey from Denbyshire, North Wales was worthwhile when they sold their pen of Beltex shearlings to top at £580 to average £548. The champion ram, was from the Hull House flock, a Castlecairn Red Arrow sired February born Texel lamb, out of a homebred ewe from John Mellin, Hellifield, Skipton, North Yorkshire this lamb sold to the pre-sale judge Richard and Jonathan Frankland on behalf Frankland Farms, Rathmell, Settle, North Yorkshire. -

Alternative York

Within these pages you’ll find the story of the York “they” don’t want to tell you about. Music, poets, : football and beer along with fights RK for women’s rights and Gay YO Liberation – just the story of AWALK another Friday night in York in fact! ONTHEWILDSIDE tales of riot, rebellion and revolution Paul Furness In association with the York Alternative History Group 23 22 24 ate ierg 20 Coll 21 e at 25 rg The Minster te Pe w 19 Lo 13 12 et 18 Stre 14 Blake y 17 one 15 C t ree 16 St St at R io o n ad York: The route oss r F ive lly R 3 t di e a 2 e cc r Pi t 5 S Clifford’s 4 r e w Tower o 1 T 26 Finish Start e t a g e s u O h g i H 11 6 e gat River Ouse lder Ske 7 e t a r g io l en e ill S k oph c h i Bis M 8 10 9 Contents Different Cities, Different Stories 4 Stops on the walk: 1 A bloody, oppressive history… 6 2 Marching against ‘Yorkshire Slavery’ 9 3 Yorkshire’s Guantanamo 10 4 Scotland, the Luddites and Peterloo 12 5 The judicial murder of General Ludd 14 6 “Shoe Jews” and the Mystery Plays 16 7 Whatever happened to Moby Dick? 18 8 Sex and the City 19 9 The Feminist Fashionista! 21 10 The York Virtuosi 23 11 Gay’s the Word! 24 12 Poets Corner 27 13 Votes for Women! 29 14 Where there’s muck… 30 15 Doctor Slop and George Stubbs 32 16 Hey Hey Red Rhino! 33 17 It’s not all Baroque and Early Music! 35 18 A Clash of Arms 36 19 An Irish Poet and the Yorkshire Miners 37 20 Racism treads the boards 38 21 Lesbian wedding bells! 40 22 The World Turned Upside Down 43 23 William Baines and the Silent Screen 45 24 Chartism, football and beer… -

2013 Draft York

YORK BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN (BAP) -- FOR LIFE Introduction What is biodiversity? Biodiversity is the huge variety of life that surrounds us, its plants, animals and insects and the way they all work together. When you are outside, in the garden, field, park, woods, river bank, wherever you are …if you look around and listen, you begin to appreciate how the immense variety of plants and wildlife that surrounds us makes our lives special. It is like a living jigsaw, each piece carefully fitting into the next, if you lose a piece, the picture is incomplete. Why is biodiversity important? – Ecosystem Services All life has an intrinsic value that we have a duty to protect and, like a jigsaw, each piece has its own part to play. The loss of one piece will affect how the next one works. We are all part of the ecosystems that surround us and so any effect on them will ultimately affect us so by protecting and helping biodiversity we are improving life for ourselves. A rich natural environment delivers numerous unseen benefits which we tend to take for granted. These are what we now call ecosystem services – things like water storage and flood control, pollination of food crops by insects even the air we breathe and the water we drink are all part of this service. There are indirect benefits as well such as improved health and wellbeing and higher property values. All of this is down to our natural environment and the biodiversity in it. Ecosystem Services Flood Storage Clean Water Carbon storage – Woods, trees, heaths Soil Food and timber Medicine Reducing heat island effects Air pollution reduction Pollination Why do we need an Action Plan? Sometimes the way we live can make life difficult for some plants and animals to survive. -

Community Sports Directory

CS426 YORK 2nd Year_Layout 1 22/01/2019 11:45 Page 1 COMMUNITY SPORTS DIRECTORY 2019 CS426 YORK 2nd Year_Layout 1 22/01/2019 11:45 Page 2 2 CS426 YORK 2nd Year_Layout 1 22/01/2019 11:45 Page 3 PAGE 3 WELCOME THIS DIRECTORY HAS BEEN PRODUCED BY CITY OF YORK COUNCIL. In the directory you will find a list of sports clubs offering a range of sporting and physical activity opportunities from Angling to Walking. There is something for everyone with activities for all ages and abilities seven days a week. QUALITY ASSURANCE The list of local clubs in this directory is for information purposes only and should not be interpreted as an endorsement of a particular club or organisation by City of York Council. However, as a guide it is recommended that anyone considering joining a particular club or organisation ensure that the club is affiliated to a relevant governing body, has appropriate insurance and where minors are involved has a robust child protection policy in place and all junior coaches are Disclosure and Barring Service checked. Disclaimer: The clubs in this directory are not recommended or endorsed by City of York Council, however we can identify the clubs who have gained Clubmark status or equivalent club accreditation awards to show they are operating to high standards in the opinion of their National Governing Body of Sport. CONTACT If you would like any information or advice on sport and physical activity opportunities, including activities for anyone with a disability or additional needs, please contact the Sport and Active Leisure team. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for the City of York

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for the City of York December 2000 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND The Local Government Commission for England is an independent body set up by Parliament. Our task is to review and make recommendations to the Government on whether there should be changes to local authorities’ electoral arrangements. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) We are statutorily required to review periodically the electoral arrangements – such as the number of councillors representing electors in each area and the number and boundaries of wards and electoral divisions – of every principal local authority in England. In broad terms our objective is to ensure that the number of electors represented by each councillor in an area is as nearly as possible the same, taking into account local circumstances. We can recommend changes to ward boundaries, and the number of councillors and ward names. We can also make recommendations for change to the electoral arrangements of parish and town councils in the district. © Crown Copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. -

Criminals and Executions in York

Criminals and16511650 Executions in York Year Name Prison Date Details Gallows Other 1379 Edward Hewison (20) York Native of Stockton, near York, private soldier in the Tuesday, 31st March After Execution, his body was Castle Earl of Northumberland‟s Light Horse. Tried and 1379. Tyburn, hanged upon a gibbet in the capitally convicted for committing rape upon Louisa without Micklegate field where he had committed Bentley, aged 22, of Sheriff Hutton, servant at that Bar. crime, in Sheriff Huuton Castle, as she was coming to York, in a field where Road. she was walking, about 3 miles from Sheriff Hutton, on Monday, 28th February, at 2.00pm. Next day Hewison taken to his quarters in the Pavement, and committed to the Castle. 1488 John Chambers York Concerned in an insurrection in the North, murdered Monday, 27th During this year a tax of a & several others Castle the Earl of Northumberland and some of his servants, November 1488, at tenth penny was laid on at Maiden Bower, Topcliffe, the seat of the Earl Tyburn, without men‟s goods and lands to aid Micklegate Bar. the Duke of Bretagne against th French King, which caused an insurrection in the North. 1537 Sir Robert Aske (58) York Native of Aughton. Leader of the Pilgrimage of Grace Wednesday 13th Next day hanged in chains Castle August 1537. upon Heworth Moor, near Beheaded in the York. Pavement. Lord Hussey (62) York Native of Duffield. Being concerned in the Pilgrimage Wednesday 27th Duffield Castle was the seat Castle of Grace. August 1537. of Lord Hussey. Hanged and Quartered at Tyburn, without Micklegate Bar. -

A New Era for Chemistry at York

Summer 2014 A new era for Chemistry WORLD TOP 100 at York MESSAGE FROM... The Vice-Chancellor s the Autumn Term approaches, it is a good time ideas and suggestions that were offered – there is a lot to say a heartfelt thank you to everyone in the to think about. Of course, there is disagreement on many University. We have had a very productive and issues (although perhaps less than one might expect), but successful academic year. We have taught more the enthusiasm with which you have engaged with the Astudents, submitted more grant applications, and produced consultation and the nature of your responses show that more top-quality articles and books than ever before. We many of us care passionately about the University and its have completed and submitted our REF return. The campus future. It is also clear that the University community is ready has continued to develop, with many projects still underway. to make the changes that are needed to address some of We have only been able to do this (and a great deal more) the challenges ahead. But most importantly, there is a great thanks to the hard work of everybody in the University. Not sense of optimism about the University and what it can all of that work is particularly glamorous, and much of it achieve in the next few years. I share that optimism. With rarely gets the explicit recognition it deserves. I want to say the Senior Management Group, I will continue to discuss that we do not take your extra efforts for granted, and I thank how your ideas, concerns and views can best be reflected you all for your contribution to the University. -

NYRA BANS BAFFERT THREE-YEAR LICENSE REVOCATION, $50K FINE for RICE's 'IMPROPER and CORRUPT CONDUCT' by T.D

TUESDAY, MAY 18, 2021 NYRA BANS BAFFERT THREE-YEAR LICENSE REVOCATION, $50K FINE FOR RICE'S 'IMPROPER AND CORRUPT CONDUCT' by T.D. Thornton Linda Rice had her training license immediately revoked for a period of "no less than three years" and was fined $50,000 May 17 when New York State Gaming Commission (NYSGC) members voted 5-0 to agree with a hearing officer that Rice's years-long pattern of seeking and obtaining confidential pre-entry information from New York Racing Association (NYRA) racing office workers was "intentional, serious and extensive, and that her actions constituted improper and corrupt conductY inconsistent with and detrimental to the best interests of horse racing." Rice had testified during eight days of NYSGC hearings late in 2020 that she had handed over cash gifts amounting to thousands of dollars at a time to NYRA racing office employees Bob Baffert | Horsephotos between 2011 and 2015. Cont. p3 by Bill Finley There was more bad news for Bob Baffert Monday, as the New York Racing Association announced that it has temporarily IN TDN EUROPE TODAY suspended the trainer, which means he will not be allowed to JOE MERCER DIES AT 86 enter any horses at NYRA tracks or occupy stall space. Former champion jockey Joe Mercer OBE has passed away at AIn order to maintain a successful thoroughbred racing 86. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. industry in New York, NYRA must protect the integrity of the sport for our fans, the betting public and racing participants,@ NYRA President and CEO Dave O=Rourke said in a statement.