Martins and Martin Houses 67 Until Several Years Had Elapsed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partnering with Your Transplant Team the Patient’S Guide to Transplantation

Partnering With Your Transplant Team The Patient’s Guide to Transplantation U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Health Resources and Services Administration This booklet was prepared for the Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). PARTNERING WITH YOUR TRANSPLANT TEAM THE PATIENT’S GUIDE TO TRANSPLANTATION U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Public Domain Notice All material appearing in this document, with the exception of AHA’s The Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights and Responsibilities, is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission from HRSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. Recommended Citation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008). Partnering With Your Transplant Team: The Patient’s Guide to Transplantation. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation. DEDICATION This book is dedicated to organ donors and their families. Their decision to donate has given hundreds of thousands of patients a second chance at life. CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1 THE TRANSPLANT EXPERIENCE .........................................................................................3 The Transplant Team .......................................................................................................................4 -

The President Woodrow Wilson House Is a National Historic Landmark and House Museum

Autumn Newsletter 2013 The President Woodrow Wilson House is a national historic landmark and house museum. The museum promotes a greater awareness of President Wilson’s public life and ideals for future generations through guided tours, exhibitions and educational programs. Above photo: Back garden evening party at The President Woodrow Wilson House. The museum also serves as a community CELEBRATING THE PRESIDENT’S Woodrow Wilson’s legacy, preservation model and resource, dedicated to one hundred years later the stewardship and CENTENNIAL presentation of an Why should anyone care about the President Wilson revived the practice, authentic collection and President Woodrow Wilson House? abandoned for more than a century, of the property. That is a fair question to consider in President delivering the State of the Union 2013, the first of eight years marking the message in person before Congress. He centennial of President Wilson’s term in regularly appeared at the Capitol to The President office, 1913–1921. promote his legislative initiatives. In a Woodrow Wilson “President Wilson imagined the world recent interview, WILSON biographer A. House is a property of at peace and proposed a plan to achieve Scott Berg noted, “There's a room in the National Trust that vision,” answers Robert A. Enholm, Congress called the President's Room. No for Historic executive director of the Woodrow Wilson president has used it since Woodrow Preservation, a House in Washington, D.C. “The Wilson. No president used it before privately funded, non- challenge he issued almost a century ago Woodrow Wilson. He used it regularly.” profit corporation, remains largely unanswered today.” Before President Wilson the national helping people protect, During this centennial period, the government played a smaller role in the enhance and enjoy the Woodrow Wilson House will be developing everyday lives of Americans than is true places that matter to exhibitions and programs to explore the today. -

A Feminist Criticism of House

Lutzker 1 House is a medical drama based on the fictitious story of Dr . Gregory House, a cruelly sarcastic, yet brilliant, doctor . Dr . House works as a diagnostician at the Princeton-Plainsboro Hospital where he employs a team of young doctors who aspire to achieve greater success in their careers . Being a member of House’s team is a privilege, yet the team members must be able to tolerate Dr . House’s caustic sense of humor . Because of Dr . House’s brilliance, his coworkers and bosses alike tend to overlook his deviant and childish behaviors . Even though Dr . House’s leg causes him to be in severe pain every day, and has contributed to his negative outlook on life, both his patients and coworkers do not have much sympathy for him . The main goals of House’s outlandish behaviors are to solve the puzzle of his patients’ medical cases . Dr . House handpicks the patients whom he finds have interesting medical quandaries and attempts to diagnose them . By conferring with his team, and “asking” for permission from Dr . Lisa Cuddy, Dr . House is able to treat the patients as he sees fit . He usually does not diagnose the patients correctly the first time . However, with each new symptom, a new piece of the puzzle unfolds, giving a clearer view of the cause of illness . Dr . House typically manages to save the lives of his patients by the end of the episode, usually without having any physical contact with the patient . Dr . House has an arrogant and self-righteous personality . Some of the lines that are written for Dr . -

Diagnosis and Treatment of Wilson Disease: an Update

AASLD PRACTICE GUIDELINES Diagnosis and Treatment of Wilson Disease: An Update Eve A. Roberts1 and Michael L. Schilsky2 This guideline has been approved by the American Asso- efit versus risk) and level (assessing strength or certainty) ciation for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and rep- of evidence to be assigned and reported with each recom- resents the position of the association. mendation (Table 1, adapted from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association Prac- Preamble tice Guidelines3,4). These recommendations provide a data-supported ap- proach to the diagnosis and treatment of patients with Introduction Wilson disease. They are based on the following: (1) for- Copper is an essential metal that is an important cofac- mal review and analysis of the recently-published world tor for many proteins. The average diet provides substan- literature on the topic including Medline search; (2) tial amounts of copper, typically 2-5 mg/day; the American College of Physicians Manual for Assessing recommended intake is 0.9 mg/day. Most dietary copper 1 Health Practices and Designing Practice Guidelines ; (3) ends up being excreted. Copper is absorbed by entero- guideline policies, including the AASLD Policy on the cytes mainly in the duodenum and proximal small intes- Development and Use of Practice Guidelines and the tine and transported in the portal circulation in American Gastroenterological Association Policy State- association with albumin and the amino acid histidine to 2 ment on Guidelines ; (4) the experience of the authors in the liver, where it is avidly removed from the circulation. the specified topic. -

Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917-1919

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 8-2013 Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917-1919 Scot D. Bruce University of Nebraska-Nebraska Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Diplomatic History Commons Bruce, Scot D., "Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917-1919" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 63. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/63 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WOODROW WILSON’S COLONIAL EMISSARY: EDWARD M. HOUSE AND THE ORIGINS OF THE MANDATE SYSTEM, 1917-1919 by Scot David Bruce A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Lloyd E. Ambrosius Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 WOODROW WILSON’S COLONIAL EMISSARY: EDWARD M. HOUSE AND THE ORIGINS OF THE MANDATE SYSTEM, 1917-1919 Scot D. Bruce, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: -

Defense Mechanism Reflected in the Character Gregory House in Tv Series House M.D Season 1-3

DEFENSE MECHANISM REFLECTED IN THE CHARACTER GREGORY HOUSE IN TV SERIES HOUSE M.D SEASON 1-3 A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For S-1 Degree in American Studies In English Department, Faculty of Humanities Universitas Diponegoro Submitted by: Nadhifa Azzahra Irawan 13020114140096 Faculty of Humanities Universitas Diponegoro SEMARANG 2017 ii PRONOUNCEMENT The writer sincerely affirms that she compiles this thesis entitled ‘Defense Mechanism Reflected in the Character Gregory House in TV Series House M.D Season 1-3’ by herself without taking any result from other researchers in S-1, S- 2, S-3, and in diploma degree of any university. The writer also emphasizes she does not quote any material from the existed someone’s journal or paper except from the references mentioned later. Semarang, 16 July 2018 Nadhifa Azzahra Irawan iii MOTTO AND DEDICATION And He found you lost and guided [you] ad-Dhuha : 7 We are here and alive in our own little corner of time. John O’Callaghan Use your mind and make it talk Cause in this world it's all you've got We all fall down from the highest clouds to the lowest ground The Answer, Kodaline This final project is dedicated for myself, and my family. iv APPROVAL DEFENSE MECHANISM REFLECTED IN THE CHARACTER GREGORY HOUSE IN TV SERIES HOUSE M.D SEASON 1-3 Written by: Nadhifa Azzahra Irawan NIM: 13020114140096 is approved by Thesis Advisor on July 27th, 2018 Thesis Advisor, Rifka Pratama, S.Hum., M.A. NPPU. H.7.199004282018071001 The Head of English Departement, Dr. -

On the Road with President Woodrow Wilson by Richard F

On the Road with President Woodrow Wilson By Richard F. Weingroff Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 2 Woodrow Wilson – Bicyclist .................................................................................. 1 At Princeton ............................................................................................................ 5 Early Views on the Automobile ............................................................................ 12 Governor Wilson ................................................................................................... 15 The Atlantic City Speech ...................................................................................... 20 Post Roads ......................................................................................................... 20 Good Roads ....................................................................................................... 21 President-Elect Wilson Returns to Bermuda ........................................................ 30 Last Days as Governor .......................................................................................... 37 The Oath of Office ................................................................................................ 46 President Wilson’s Automobile Rides .................................................................. 50 Summer Vacation – 1913 ..................................................................................... -

Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 the 7 Key Principles of Successful Recovery: the Basic Tools for Progress, Growth, and Happiness B., Mel

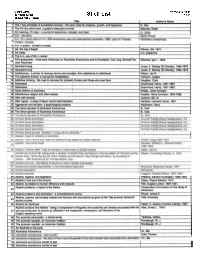

Griffith Library 07/25/0514:13:40 38 Village Street Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 The 7 key principles of successful recovery: the basic tools for progress, growth, and happiness B., Mel. 2 The 24 hour drink b~u!de to executive survival. Maloney, Ralph. --- 61 A.A. in prison: inmate to inmate. 71 AA, the way it began I Pittman, Bill, 1947-_1 way of life; a reader 10I AA's godparents: three early influences on Alcoholics Anonymous and its foundation, Carl Jung, Emmet Fox, Sikorsky, Igor I., 1929- I Jack Alexander 11 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973:l 12 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973. I 13 Addictionary: a primer of recovery terms and concepts, from abstinence to withdrawal Wilson, Jan R. I 14 The addictive drinker; a manual for rehabilitation. Thimann, Joseph. I 15 Addictive drinking: the road to recovery for problem drinkers and those who love them Vaughan, Clark. I 16 Addresses Drummond, Henry, 1851-1897. 171 Addresses I Drum~o_nd._Henry. 1851-~~97. 181 Adult children of alcohoTi-cs ~ Woititz, Janet Geringer. 191 Adventurous religion and other essays Fosdick, Harry Emerson, 1878-1969. 20 Afire with serenity Jackson, Bill, Dr. 21 After repeal: a study of liquor control administration Harrison, Leonard Vance, 1891- 22 Aggression and altruism, a psychological analysis. Kaufmann, Harry. 23 The Akron genesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B., Dick. 24 The Akron qenesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B. Dick. Alcohol, hygiene, and legislation EdwardHu~ington!~~ 411 Alcohol in and out of the church lOates,_~ayne Edward, 1917- ~IXcohof; Its relation to human efficiency and longevity Fisk, Eugene Lyman, 1867-1931.~ Alcohol problems; a report to the Nation. -

Annual Report 2015

Making Transplant Families FEEL AT HOME. 2015 Annual Report A MESSAGE from the President Dear Friends, 580 families. 8,439 nights. 17,734 miles. 31,696 meals. Because of the generosity of 1 incredible community. Tara, transplant recipient I am so proud and in awe of the Gift of Life community and the loving support you continue to extend to transplant patients and their families. Especially to the families who rely on Gift of Life Family House as their “home away from home” for days, weeks, sometimes even months while they or their loved one It’s really nice to know that receives life-saving transplant care here in Philadelphia. 2015 was an amazing year! With your help, we served more families than ever before. Our dedicated shuttle volunteers driving families to and from area hospitals, our fantastic Home Cook Heroes serving up warm and delicious meals, along with our social worker and other caring families here at the House guiding guests through their transplant journey. And thanks to your support of our Adopt-A-Family Program, we have never had to turn a family away due “someone understands what to their inability to pay our nightly fee. Thank you so much for everything you do to make our House a home! This Annual Report demonstrates the impact the Family House has had on the transplant community in 2015 – but more importantly, it demonstrates just you’re going through. This is how much YOU have touched the lives of so many of our families. Thank you for standing beside us in our mission, both now and in the years to come. -

Woodrow Wilson and “Peace Without Victory”: Interpreting the Reversal of 1917

Woodrow Wilson and “Peace without Victory”: Interpreting the Reversal of 1917 John A. Thompson In a speech to the Senate on January 22, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson called for the European war to be brought to an end through “a peace without victory.” This, he argued, was the only sort of peace that could produce a lasting settlement: Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor’s terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory President Woodrow Wilson upon which the terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand. 1 Wilson went on to outline what he saw as the other “essential” elements of a lasting peace. Such a settlement would need to be based on such principles “as that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed and that no right anywhere exists to hand peoples about from sovereignty to sovereignty as if they were property,” recognition of the rights of small nations, freedom of the seas, and limitation of armaments on both land and sea. Above all, it required that the settlement be underwritten “by the guarantees of a universal covenant,” that it be “a peace made secure by the organized major force of mankind.” 2 John A. Thompson is emeritus reader in American History and an emeritus fellow of St Catharine’s College, University of Cambridge. He thanks Ross A. Kennedy for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article. -

House Md, Season 3, Episode 20 House Training

House md, Season 3, episode 20 House Training This episode concerns issues of how we make decisions in our lives, and how we receive forgiveness for the bad ones. Synopsis A young scam artist is working a ‘find the lady’ routine in the street when she realises she can’t think properly or make decisions: ‘I can’t decide’. She collapses and is admitted to Dr House’s care. Hearing about her, House says ‘Loss of free will. I like it. Maybe we can get Thomas Aquinas in for a consult.’ Dr Foreman talks to her and finds out how she has a job for just long enough to claim benefits and then leaves. He judges her for playing the system which she picks up on. She argues that they are alike except that she made some bad decisions, but Foreman denies this. Foreman is unimpressed that she took some hits off a crack pipe to feel ‘happy’. While the team try to find out what’s wrong with her, various personal issues come into play. Dr Foreman is approached by his father to visit his mother who has Alzheimers as it’s her 60th birthday. Although he hasn’t been home in 8 years, Dr Foreman goes to his parents’ hotel room and is pleased to find that his mother seems happy and lucid. She also asks him if he’s happy and has friends and if he still prays. Meanwhile Dr Chase says he will tell Dr Cameron once a week, on Tuesdays, that he likes her and wants a relationship with her; even though she says she doesn’t want to be with him. -

Adult Heart Transplant Handbook

THE ADULT HEART TRANSPLANT HANDBOOK A REFERENCE GUIDE FOR HEART TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS, THEIR FAMILIES, AND CAREGIVERS. This reference guide belongs to: Patient Name: Transplant Date: HEART TRANSPLANT PROGRAM Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Advanced Health Sciences Pavilion 127 S. San Vicente Blvd., Suite A6100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 USA Tel: (310) 423-5460 Fax: (310) 423-0852 www.cedars-sinai.edu/heart In the event this handbook is lost and found, please be advised: The information contained herein is considered Protected Health Information (PHI) and is protected under applicable law. This personal identifiable health information is private, confidential, and privileged. Any review, dissemination, distribution, or disclosure in any manner whatsoever is strictly prohibited and violations committed thereon are prosecuted. Upon immediate determination that handbook has been lost, please secure its safety and call the Heart Transplant Program at (310) 423-5460 and arrange for its return at the expense of the hospital. Thank you for your cooperation. Foreward 5 PREFACE This handbook is designed to provide a better understanding of the heart transplant program, the associated postoperative recovery, and the lifetime follow-up care required of all heart transplant recipients. Please consult with a transplant nurse coordinator, transplant cardiologist, or other appropriate clinician to assist you in finding answers to the questions you could not find in this handbook. Contents 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .........................................................................................