OCIC/Unda: the First International Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5Th SIGNIS East Asia Conference on 'Family and Stories of Hope'

Volume : 4 January 2018 Issue : 10 Asia World Catholic Association 5tforh Social SI CommunicationGNIS East Asia Conference on 'Family and Stories of Hope’ In response to the deep concern on 'Family' by our Holy Father a 'vicious circle of anxiety'. Wars, terrorism, scandals and all Pope Francis, a Two day conference on the theme 'Family and sorts of human failures. It brings indifference, fear and create Stories of Hope' was held at YMCA Asia Youth Centre, Tokyo, resignation among people. But there is another world. Shouldn't Japan on 11-12 November 2017. we direct our 'lens' to the 'good news' of Hope and Trust we Around 40 scholars and media professionals from East Asian can find around ourselves which the mass media does not countries (Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Macau and Taiwan) bother, and communicate these to our societies?' Mr. Itaru said, participated in the event organized by SIGNIS Japan. 'Let's not treat 'family' in a narrow sense, but search for the challenges, common to East Asia such as children, youth, and Mr. Tsuneaki Mac Machida, the Secretary of Signis Japan was the elderly persons'. the Chief Coordinator of the conference. SIGNIS, a Bridge between Nations! Media Ignore People! Rev. Ryohei MIYASHITA, the Secretary General of Catholic The East Asia conference was officially started with a video Bishops Conference of Japan said, 'Japan and South Korea have recorded address by Most Rev. James Kazuo Koda, Auxiliary conflicts politically but we meet once a year and talk to each Bishop of Tokyo Archdiocese. He said, 'Through TV and other other which stands as testimony for our Relationship. -

Radio Radio As Peacemaker Eyecatcher

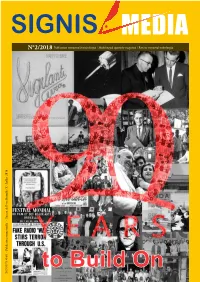

SIGNIS MEDIA N°2/2018 Publication trimestrielle multilingue / Multilingual quarterly magazine / Revista trimestral multilingüe ISSN 0771-0461 - Publication trimestrielle - Bureau de Poste Bruxelles X - Juillet 2018 X - Juillet Bruxelles de Poste trimestrielle - Bureau ISSN 0771-0461 - Publication to Build On Contents 4 Cover Story 90 Years to Build On 18 Journalism Safety of Journalists 12 Cinema Presence in the Festivals 20 Radio Radio as Peacemaker Eyecatcher SIGNIS VJ Stanley Hector at Cannes Stanley Hector, 23, from SIGNIS India had his latest short film screened at the International Cannes Film Festival, among 19 from India. Entitled Midnight at 2, it was shot and produced in Indore in May 2017 and is his sixth short film. The story revolves around two strangers, a girl and a boy, sharing a moment of profound silence on the balconies of their homes at 2 am. Everything started for Stanley during a college event where he made promotional videos for his college’s E-Cell (an initiative by National Entrepreneurship Network) and gained instant appreciation for the medium. His first short film, Pedal which found its place among the top 10 national submissions of IIT Indore’s cultural festival, Fluxus, was selected by Pocket Films, an online YouTube channel for short film promotion, and was also nominated at the Sutradhar Film Festival, Indore, and submitted to the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, for judging. His second short film, The Wall was screened at the SIGNIS Film Festival in Malaysia and Patna. Pocket Films also picked it up. Stanley attended the 2015 Artisans for a Culture of Peace SIGNIS media workshop (now known as CommLab) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. -

From Across the Ocean

March 2007 No 1 Above: Bp Peter Ingham, President, Oceania Bishops Conference and Chair, Australian Catholic Film and Broadcast Office. Below: Joe Vidiki, Solomon Islands and Leopold Ariipeu, Tahiti From Across the Ocean They came from small island nations such as Wallis and Futuna, large but poor countries like Papua New Guinea, coral atolls such as Kiribati and politically unstable states like Tonga, Fiji and the Solomon Islands. Twenty two people from fourteen Pacific nations arrived in Melbourne, Australia, for the SIGNIS Pacific Assembly and Training Workshop, February 5-9, 2007. Some came as SIGNIS Pacific delegates and others to participate in the training workshop. For many it was a struggle to come. The cost of travel is high and the planes infrequent and often unreliable. Delegates gave reports on media activity in their country particularly the media apostolate of the church in radio, television, cinema, internet, video and related media. President: Mr Bill Falakaono, Tonga. Vice President: Mdm. Nicole Constans, New Caledonia. Sec/Treasurer: Mr Peter Thomas, Australia. SIGNIS Pacific News is published by SIGNIS Pacific, Box 12, 16 Armstrong Street, Middle Park Vic 3126, Australia. Tel: 61 3 9682 1085. Fax: 61 3 8611 7956 Mbl: 0419 899 199. Email: [email protected] SIGNIS Pacific is part of SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication. SIGNIS Pacific News No 1 – March 2007 – page 1 Left: Recording a drama in preparation for the Editing Workshop. Right: Maurae Arawaia and Eritabeta Buoa from Kiribati editing at the Editing Workshop. With six Apple Macintosh G5 computers loaded with Final Cut Pro editing software, Chris Downey, an associate member of SIGNIS Pacific, and a well- known Australian freelance Editor, taught the participants the joys of modern digital editing techniques. -

Issue 26 (2019)

IDF IDF Faunistic Studies in Southeast Asian and Pacific Island Odonata Journal of the International Dragonfly Fund 146 Milen Marinov, Seth Bybee, Crile Doscher & Donna Kalfatakmolis Faunistic studies on Odonata of the Republic of Vanuatu (Insecta: Odonata) published 10.02.2019 No. 26 ISSN 21954534 The International Dragonfly Fund (IDF) is a scientific society founded in 1996 for the impro vement of odonatological knowledge and the protection of species. Internet: http://www.dragonflyfund.org/ This series intends to contribute to the knowledge of the regional Odonata fauna of the Southeastern Asian and Pacific regions to facilitate costefficient and rapid dissemination of faunistic data. Southeast Asia or Southeastern Asia is a subregion of Asia, consisting of the countries that are geographically south of China, east of India, west of New Guinea and north of Austra lia. Southeast Asia consists of two geographic regions: Mainland Southeast Asia (Indo china) and Maritime Southeast Asia. Pacific Islands comprise of Micronesian, Melanesian and Polynesian Islands. Editorial Work: Martin Schorr, Milen Marinov and Rory Dow Layout: Martin Schorr IDFhome page: Holger Hunger Printing: Colour Connection GmbH, Frankfurt Impressum: Publisher: International Dragonfly Fund e.V., Schulstr. 7B, 54314 Zerf, Germany. Email: [email protected] Responsible editor: Martin Schorr Cover picture: Neurothemis stigmatizans bramina, Ewor River, Efate Island Photographer: Milen Marinov Published 10.02.2019 Faunistic studies on Odonata of the Republic of Vanuatu (Insecta: Odonata) Milen Marinov1, Seth Bybee2, Crile Doscher3, Donna Kalfatakmolis4 1Plant Health & Environment Laboratory, Diagnostic and Surveillance Services, Ministry for Primary Industries, 231 Morrin Rd, 1072 Auckland, New Zealand Email: [email protected] 2Biology Department & Monte L. -

The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection

The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection (Front illustration: the Sun without spots, July 27, 1954) By Willie Wei-Hock Soon and Steven H. Yaskell To Soon Gim-Chuan, Chua Chiew-See, Pham Than (Lien+Van’s mother) and Ulla and Anna In Memory of Miriam Fuchs (baba Gil’s mother)---W.H.S. In Memory of Andrew Hoff---S.H.Y. To interrupt His Yellow Plan The Sun does not allow Caprices of the Atmosphere – And even when the Snow Heaves Balls of Specks, like Vicious Boy Directly in His Eye – Does not so much as turn His Head Busy with Majesty – ‘Tis His to stimulate the Earth And magnetize the Sea - And bind Astronomy, in place, Yet Any passing by Would deem Ourselves – the busier As the Minutest Bee That rides – emits a Thunder – A Bomb – to justify Emily Dickinson (poem 224. c. 1862) Since people are by nature poorly equipped to register any but short-term changes, it is not surprising that we fail to notice slower changes in either climate or the sun. John A. Eddy, The New Solar Physics (1977-78) Foreword By E. N. Parker In this time of global warming we are impelled by both the anticipated dire consequences and by scientific curiosity to investigate the factors that drive the climate. Climate has fluctuated strongly and abruptly in the past, with ice ages and interglacial warming as the long term extremes. Historical research in the last decades has shown short term climatic transients to be a frequent occurrence, often imposing disastrous hardship on the afflicted human populations. -

The Virgin Mother of Good Counsel

More Free Items at www.catholickingdom.com THE VIRGIN MOTHER GOOD COUNSEL. A HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT SANCTUARY OF OUR LADY OF GOOD COUNSEL IN GENAZZANO. AND OF THE WONDERFUL APPARtTION AND MIRACULOUS TRANSLATION OF HER SACRED IMAGE FROM SCUTARI IN ALBANIA TO GENAZZANO IN 1467. WITH AN APPESDIS ON THE XIBACULOUS CRUCIFIX, SAN PIO, ROMAN ECCLESIASTICAL EDUCATIOR ETC. BY THE REVD. GEORGE F. UILLON D. D. A VIB~T?JR FROM SYDIEY TO TlSE RIIRTSE ROME PRIXTED AT THE OFFICES OF THE SACRED COSGREGATIOX OF THE PROI'AGAXDA FIDE 1884. [The uzrthor rcsztT1es 1111 rigbtj of reprirrfing ltnd frartslation.] PRIVATE USE ONLY TO THE MOST EMINENT AND MOST REVEREND THOMAS M. CARDINALMARTINELLI, PBEPECT OF !CHE 8ACRED CONGREGATION OF THE INDEX, ETC. ETC. Most Eminent Prince, The writer, with the deepest sense of gratitude, taking advantage of your kind permission, - a permission all the more valued because never accorded to any author before - most respectfully dedicates this book to Your Eminence. The reason why Your Eminence has been pleased to grant this permission is not, in this particular instance, difficult to understand. The work treats of a venerable Sanctuary of Our Lady confided to Fathers of the great Order of which you are Cardinal Protector. It aims, according to the humble ability of the writer, at extending the deep and tender devotion to the More Free Items at www.catholickingdom.com Immaculate Virgin Mother of God, so characteristic of the land of your birth, and so specially dear to you, to the people to whom the miter belongs, - a people whom you love, and whose widespread migrations have carried the Faith whose purity Your Eminence as Cardinal Prefect of the Index, guards so ably and so vigilantly, to many parts of the world. -

Ecumenical Jury Cannes Festival

CANNES 2013 ECUMENICAL JURY 40th year CANNES FESTIVAL The Ecumenical Jury awards a Prize to a film from the official Competition http://cannes.juryoecumenique.org Press file 15 - 26 May 2013 CONTACT Press officer: Louisiane Arnera - Mobile: +33 (0)6 13 07 20 50 Ecumenical Jury Stand - Level 01 - Row 18/03 - Tel. +33 (0)4 92 99 80 62 E-mail: [email protected] - http://cannes.juryoecumenique.org CANNES 2013 1. THE ECUMENICAL JURY 2013 Denyse MULLER (France), President Pastor Denyse Muller, spent her childhood and adolescence in Cannes. She has a Master’s Degree in Protestant Theology (Montpellier). She undertook further studies in Chicago and Richmond (USA). She then undertook pastoral ministry in Virginia (USA) and in the Reformed Church of France (EPUdF) and the Protestant Church of Geneva (Switzerland). She is currently a member of Pro-Fil and board member of WACC Europe. Since 2000, she has been the co-organizer with SIGNIS of the Ecumenical Jury at Cannes, and since 2003, Vice-President of INTERFILM and President of INTERFILM France. Member of Ecumenical Juries in Berlin, Cannes, Locarno, Montreal, Karlovy Vary, Yerevan, Warsaw etc. Marek LIS (Poland) Father Marek LIS has a doctorate in social communications from the Salesian University in Rome. He was editor-in-chief of the Catholic radio station for the Diocese of Opole (Poland). Since 2000 he has been Professor of theology at the University of Opole, where he teaches theology, film, media and communication. He studies the relationship between religion and cinema, conducts research and has written numerous articles and books on the religious dimension, sometimes hidden, of films. -

Raskob Foundation for Catholic Activities, Inc. Grants Approved

Raskob Foundation for Catholic Activities, Inc. Grants Approved Report - 2011 International Grants: Angola Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Province of Angola $21,000 Luanda, Angola Toward salaries of coordinator/instructors, materials and equipment to conduct vocational training courses at a center in Santo Andre oblate parish in cooking/baking, interior decorating and hospitality/hotel management for young women unable to attend school during the 27-year civil war because of poverty, being orphans/refugees or lack of functioning schools. Argentina Sain t Juan Diego Parish $16,000 Tigre, State of Buenos Aires, Argentina Toward books, didactic materials, and salaries for Our Lady of Guadalupe nursery school and kindergarten. Austria Jugend Eine Welt Don Bosco Aktion Austria (JEW) $25,000 Vie nna, Austria For salaries, travel and lodging, equipment/furnishings, motorcycle, maintenance/rent/utilities, provisions and health care to create a 24-hour Salesian Center (Safe Haven) in Freetown, Sierra Leone for girls, ages 8 to 17, who are sexually abused and exploited. Belgium SIGNIS (The World Catholic Association for Communication) $10,000 Brussels, Belgium Toward travel expenses, room and board, equipment and local transportation of youth participants, signis trainer and media mentors attending World Youth Day 2011 in Madrid, Spain. Benin The Center for Research Studies and Creativity $20,000 Godomey, Benin Toward program expenses, training materials, curriculum development, lodging, transportation, and meals to provide training to religious in the republic of Benin and communities of Togo to counsel adults and married couples on domestic violence. Raskob Foundation for Catholic Activities, Inc. Grants Approved Report - 2011 Bolivia Daughters of Charity of St. -

SIGNIS Canonical Statutes 1. Name 2. Registered Office 3. Objectives Of

SIGNIS Canonical Statutes 1. Name SIGNIS: the World Catholic Association for Communication is a public international association of the faithful regulated by canons 298-320 and 327-329 of the Code of Canon Law whose statutes have been approved by the Pontifical Council for the Laity. SIGNIS will collaborate regularly with the Secretariat of State in matters concerning its activities in relation to international organizations. 2. Registered office 2.1. The Registered Office of the Association is in Fribourg, Switzerland. (Rue de Lausanne, 86, C.P. 271, 1701 Fribourg). 2.2. The Association has an Administrative Office in Belgium. 2.3. The Registered Office and/or the administrative office may be transferred to any other location or country by a decision of the Assembly of Delegates passed by two thirds of the votes. 3. Objectives of SIGNIS 3.1. SIGNIS is a world Catholic Association of groups and individuals engaged in communication and media who, inspired by the teachings of Jesus Christ, have as their goal the promotion of the personal, social and cultural life of each human being and their the community. 3.2. The objectives of the Association are: 3.2.1. To promote a Christian understanding of the importance of human communication in all cultures. 3.2.2. To engage in activities which motivate and encourage participation in the betterment of the communications environment on the basis of Christian values. 3.2.3. To be open to and promote ecumenical and inter-religious collaboration in communication activities. 3.2.4. To promote communication policies that respect Christian values, justice and human rights. -

Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in the Medieval West

Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in the Medieval West The International Library of Historical Studies Series ISBN 1 86064 079 6 Editorial Board: Professor David N.␣ Cannadine, Director, Institute of Historical Research, University of London; Wm. Roger Louis, Dis- tinguished Teaching Professor and Kerr Chair in English History and Culture, University of Texas, Austin; Gene R. Garthwaite, Jane and Raphael Bernstein Professor of Asian Studies, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire; Andrew N. Porter, Rhodes Professor of Imperial History, King’s College London; Professor James Piscatori, Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies and Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford; Professor Dr Erik J. Zürcher, Chair, Turkish Studies, University of Leiden Series Editors: Andrew Ayton, University of Hull (medieval history); Christopher J. Wrigley, Professor of Modern British History, University of Nottingham The International Library of Historical Studies (ILHS) brings together the work of leading historians from universities in the English-speaking world and beyond. It constitutes a forum for original scholarship from the United Kingdom, continental Europe, the USA, the Common- wealth and the Developing World. The books are the fruit of original research and thinking and they contribute to the most advanced historiographical debate and are exhaustively assessed by the authors’ academic peers. The Library consists of a numbered series, covers a wide subject range and is truly international in its geographical scope. It provides a unique and authoritative resource for libraries -

Eosg / Central Civil Society Report at Midpoint of Culture of Peace Decade

PERMANENT MISSION OBJBA TO THE UNITED N 227 East, 45* Street 14* Floor, New Yorfc, NY 10017 Tel: (212) 867-3434 • Fax: (212) 972-4038 • E-mail: [email protected] web site: www.un.tnt/Bangladesb. Y Ambassador and Permanent Representative NO.UNGA-58/COP/03 29 June 2005 Sub: Civil Society Report at Midpoint of Culture of Peace Decade. Dear Mr. Secretary-General, I wish to draw your Attention to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolutions 53/25 of 10 November 1998, 55/47 of 22 January 2001 as well as 59/143 of 25 February 2005 regarding the International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-violence for the Children of the World, 2001- 2010, tabled by Bangladesh and co-sponsored by many Member States. Resolution 53/25 proclaimed the period 2001-2010 the International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-violence for the Children of the World, resolution 55/47 requested the Secretary-General to submit to the 60th UNGA a report on the observance of the Decade at its mid-point and on the implementation of the Declaration and Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace, and resolution 59/143 invited Member States as well as civil society, including non-governmental organizations, to provide information to the Secretary-General on the observance of the Decade and the activities undertaken to promote a culture of peace and non-violence. The Fundacion Cultura de Paz of Connecticut, USA, has compiled reports on the activities of some 700 civil society organizations from over 100 countries on a Culture of Peace. -

Newsletter 1

SIGNIS Pacific News No. 3 November 2007 CHILDREN OUR FIRST CONCERN AND HOPE FOR THE FUTURE By Agatha Ferei We try to empower people dignity of the human person SIGNIS Fiji to become pro-active me- by empowering the use of the dia users rather than passive media in a way that enhances Parents and leaders need consumers, to equip them rather than diminishes that help to prepare children to with the skills they need to dignity. Some see this endea- live in and cope with the new be critical, selective as appre- vour as a valid form of pre- media culture as there is little ciative readers, listeners and evangelisation. doubt that the mass media is viewers. This has the added the dominant media culture effect of building personal throughout the world. This is autonomy and developing no less the case with the small critical thinking skills in a isolated Pacific island nations, country where the ‘culture including the Fiji Islands. of silence’ still holds sway. It encourages people to partici- At Fiji Media Watch, where I pate in community and public am Media Education Coordi- policy decision-making and so nator, our aims are to foster grow into mature responsible public awareness of the role of citizens. the media, to promote media education and to monitor the media for quality of con- Fiji Media Watch is non-de- tent. Established in 1993, its nominational and embraces members are educational and all of Fiji’s multi-cultural and religious organizations and multi-religious people. It is concerned citizens. committed to promoting In This Issue About Us SIGNIS Pacific News is published by: SIGNIS Pacific, Box 12, 16 Armstrong Street, Middle Park Vic.