103-115 Lani MN.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kitchen Art's Xmas Hi Tea Buffet Menu 2017 Santa's Farm 5 Types Of

Kitchen Art’s xmas Hi Tea Buffet Menu 2017 Santa’s Farm 5 types of Lettuce 6 types of fresh Vegetables Penang Rojak Buah with Condiments German Potato Salad, Peruvian Ceviche, Thai Beef Salad, 3 types of Kerabu 1000 Island Dressing, French Dressing, Sesame Dressing ,Thai Mayo Dressing, Italian Vinaigrette, Balsamic Vinaigrette ,Olive Oil Dressing and Aioli Vinaigrette served with 6 types of condiments Soup Cream of Tomato Basil Soup Bread Counter Assorted Bread Roll & Loaf served with Butter and 2 types of Jam Stall 1: Santa Goes Chinese Roasted Chicken Char Siew served with Chinese style Fragrant Rice, Clear Soup and Condiments Stall 2: Santa Goes Indian Briyani Rice with Briyani Chicken, Onion Raita and Papadom Roti Canai with Chicken Curry and Vegetable Dhall Stall 3: Santa Goes Western Roasted Herb Turkey and Lamb Leg served with Herbed Potato Chuck and Buttered Vegetables accompanied with Rosemary au Jus and Mint sauce. Assorted pizza Stall 4: Santa Goes Malay Gorengan – Cucur Pisang, Keledek Goreng, Jemput-Jemput & Keropok Lekor with condiments Malaysian Satay with condiments Laksa Utara with condiments Stall 5: Santa Goes Middle east Mediterranean Beef Kebab with Cucumber Raita, Tzatziki sauce and Spice sauce Mrs Klause’s Favourites Steam Rice Jollof Rice Puttanesca Pasta Roasted Maple Chicken with Italian BBQ sauce Sesame Beef Ginger Lamb Varuval Sweet and Sour Fish Roasted Herb Potato Mix Vegetable with Herb Butter Kid’s factory Pop Corn Chicken Nugget Fillet Cheesy Sweet Potato Cotton Candy Chocolate Fountain with condiments ABC & Ice Cream with condiments Sweetness Xmas Assorted French Pastries Assorted Fruit Tartlets Assorted Mousse in Glass Xmas Pudding Assorted Nyonya Kuih (2 Type) Gingerbread Man Assorted Cookies (4 types) Bubur Jagung Bread & Butter Pudding with Vanilla sauce Seasonal Fruit Platter (4 types) . -

Kuaghjpteresalacartemenu.Pdf

Thoughtfully Sourced Carefully Served At Hyatt, we want to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising what’s best for future generations. We have a responsibility to ensure that every one of our dishes is thoughtfully sourced and carefully served. Look out for this symbol on responsibly sourced seafood certified by either MSC, ASC, BAP or WWF. “Sustainable” - Pertaining to a system that maintains its own viability by using techniques that allow for continual reuse. This is a lifestyle that will inevitably inspire change in the way we eat and every choice we make. Empower yourself and others to make the right choices. KAYA & BUTTER TOAST appetiser & soup V Tauhu sambal kicap 24 Cucumber, sprout, carrot, sweet turnip, chili soy sauce Rojak buah 25 Vegetable, fruit, shrimp paste, peanut, sesame seeds S Popiah 25 Fresh spring roll, braised turnip, prawn, boiled egg, peanut Herbal double-boiled Chinese soup 32 Chicken, wolfberry, ginseng, dried yam Sup ekor 38 Malay-style oxtail soup, potato, carrot toasties & sandwich S Kaya & butter toast 23 White toast, kaya jam, butter Paneer toastie 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, sour dough bread S Roti John JP teres 36 Milk bread, egg, chicken, chili sauce, shallot, coriander, garlic JPt chicken tikka sandwich 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, egg JPt Black Angus beef burger 68 Coleslaw, tomato, onion, cheese, lettuce S Signature dish V Vegetarian Prices quoted are in MYR and inclusive of 10% service charge and 6% service tax. noodles S Curry laksa 53 Yellow noodle, tofu, shrimp, -

PDF Download Growing up in Trengganu

GROWING UP IN TRENGGANU PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Awang Goneng | 336 pages | 15 Sep 2007 | Monsoon Books | 9789810586928 | English | Singapore, Singapore Growing Up in Trengganu PDF Book But his prose is 'mengkhayalkan' and there are many quotable quotes, among my favourites being "The past may be another country, but there you know many people. Tigers were once common in Malaysian jungle but are now declining in the number, this happen too to the elephants. I was so absorbed when I read this that my mind swirled with imaginations. This was a pretty colossal endeavour — a flotilla of or so international media converging upon the high seas in the hunt for squid and squid related stories. Of course, one cannot write a book about Trengganu [or Terengganu for that matter] without putting in some Trengganuspeak. A must read book for those who grew up in the East Coast of Malaysia. Fishermen home from the sea for a long snooze on the veranda, awaiting the wife's return with tapioca and stuff. Progress here is from inchoate feelings for space and fleeting discernments of it in nature to their public and material reification. Photo courtesy of Malaysian Timber Council. This sleaze cafe came back to me when I was watching an early instalment of Star Wars, when Hans Solo and friends ventured into the cafe at the edge of the universe, filled with shady types and blubbery people. Apa yang diperlihatkan buat kali kedua oleh golongan nelayan bukannya merupakan yang terakhir, namun mendorong suatu perancangan festival tahunan dengan pendekatan baharu termasuk pertandingan perahu tradisional di samping pameran dan jualan yang berkaitan dengan laut. -

DARI DAPUR BONDA Menu Ramadan 2018

DARI DAPUR BONDA Menu Ramadan 2018 MENU 1 Pak Ngah - Ulam-Ulaman Pucuk Paku, Ubi, Ulam Raja, Ceylon, Pegaga, Timun, Tomato, Kubis, Terung, Jantung Pisang, Kacang Panjang and Kacang Botol Sambal-Sambal Melayu Sambal Belacan, Tempoyak, Cili Kicap, Budu, Cencaluk, Air Asam, Tomato Sauce, Chili Sauce, Sambal Cili Hijau, Sambal Cili Merah, Sambal Nenas, Sambal Manga Pak Andak – Pembuka Selera Gado-Gado Dengan Kuah Kacang / Rojak Pasembur Kerabu Pucuk Paku, Kerabu Daging Salai Bakar Kerabu Manga Ikan Bilis Acar Buah Telur Masin, Ikan Masin, Tenggiri, Sepat, Gelama Dan Pari Keropok Keropok Ikan, Keropok Udang, Keropok Sotong, Keropok Malinjo, Keropok Sayur & Papadom Pak Cik- Salad Bar Assorted Garden Green Lettuce with Dressing and Condiments German Potato Salad, Coleslaw & Tuna Pasta Assorted Cheese, Crackers, Dried Fruit and Nuts Pak Usu – Segar dari Lautan Prawn, Bamboo Clam, Green Mussel & Oyster Lemon Wedges, Tabasco, Plum Sauce & Goma Sauce Jajahan Dari Timur - Japanese - Action Stall Assorted Sushi, Maki Roll & Sashimi - Maguro, Salmon Trout & Octopus Pickle Ginger, Shoyu, Wasabi Jajahan Dari Timur -Teppanyaki Prawn & Chicken with Vegetables Pak Ateh -Soup Sup Tulang Rusuk Cream of Pumkin Soup Assorted Bread & Butter Ah Seng - Itik & Ayam - Action Stall Ayam Panggang & Itik Panggang Nasi Ayam & Sup Ayam Chili, Kicap, Halia & Timun Mak Usu - Noodles Counter -Action Stall Mee Rebus, Clear Chicken Soup & Nonya Curry Laksa Dim Sum Assorted Dim Sum with Hoisin Sauce, Sweet Chilli & Thai Chilli Pak Uda - Ikan Bakar- Action Stall Ikan Pari, Ikan -

Kitchen Art's Brasserie

KITCHEN ART’S BRASSERIE MENU BUFFET HI-TEA MENU A 2020 Garden Salad 4 Type of Lettuce, 4 Type of Kerabu, 2 Type Toast Salad Dressings and Condiments Homemade Pickled Shallot, Sesame Seed and Crusted Nut Thousand Island, Caesar Dressing, Italian Vinaigrette, Roasted Sesame Dressing, Honey Soya Dressing Balsamic Vinegar and Olive Oil Fruit Counter Rojak Buah Serves with Condiment Italian Counter BBQ Pizza Margarita Pizza Soup Cream of Mushroom Soup Serves with Bread Loafs, Bread Rolls & Butter Sauna Box Assorted Mini Pau Noodle Action Live Laksa Penang with Condiment Counter on Fire Satay Chicken & Satay Beef Serves with Peanut Sauce, Cucumber, Onion and Rice Cake Stall 1 Pasembor Serves with Condiments Stall 2 Rotisserie Chicken Serves with Au Jus, Sautéed Mix Vegetable & Potato Stall 3 Nasi Biryani Ayam Biryani Acar Mentah Stall 4 Shawarma Greek Style Chicken Shawarma Serves with Lettuce, Tzatziki Sauce, Tomato & Cucumber Main Fair Kampung Fried Rice Singapore Fried Mee Hoon Sweet & Sour Fish Mutton Curry with Potatoes Stir Fried Mix Vegetables Buffalo Chicken Wing Beef Lasagna Roasted Baked Duo Potatoes Kid’s Station Chocolate Fountain with Condiments Caramelized Popcorn Popia Sambal & Samosa Desserts Assorted Nyonya Kuih Sago Gula Melaka Bread Butter Pudding Assorted Jelly in the Glass & Crème Caramel, 4 type of Ice Cream with Condiments Fresh Cut Tropical Fruits Hot & Cold Sweet Congee Chilled Longan Bubur Kacang HI TEA MENU B 2020 Garden Salad 4 Type of Lettuce, 4 Type of Kerabu, 2 Type Toast Salad Dressings and Condiments Homemade -

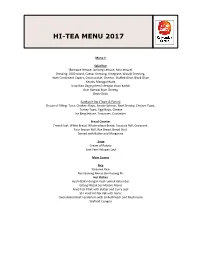

Hi-Tea Menu 2017

HI-TEA MENU 2017 Menu 1 Salad bar (Romaine lettuce, Ice berg Lettuce, Mix Lettuce) Dressing: 1000 Island, Caesar Dressing, Vinegrate, Wasabi Dressing, With Condiment Capers, Onion pickle, Gherkin, Stuffed Olive, Black Olive Kerabu Mangga Muda Urap Ikan Daging Bercili dengan Daun Kadok Acar Rampai Bijan Goreng Gado-Gado Sandwich Bar (Toast & Panini) Choice of Filling: Tuna, Chicken Mayo, Smoke Salmon, Beef Streaky, Chicken Toast, Turkey Toast, Egg Mayo, Cheese Ice Berg lettuce, Tomatoes, Cucumber Bread Counter French loaf, White Bread, Whole wheat Bread, Focaccia Roll, Croissant, Four Season Roll, Rye Bread, Bread Stick Served with Butter and Margarine Soup Cream of Potato Tom Yam Hidupan Laut Main Course Rice Steamed Rice Nasi Goreng Nenas dan Kacang Pis Hot Dishes Ayam Bakar dengan Kuah Lemak Ketumbar Udang Masak Sos Masam Manis Fried Fish Fillet with Butter and Curry Leaf Stir Fried HK Nai Pak with Garlic Oven Baked Beef Tenderloin with Grilled Peach and Mushroom Seafood Lasagna Noodle Stall 3 Type of Soup (Curry Mee, Tom Yam and Chicken Soup) Noodles: Dried Noodles, Yellow Mee, Wanton Mee, Kway Teow and Mee Hoon) 6 Types Of Vege: cabbage, Kangkong, Kai Lan, Choy Sum, Bean Sprouts, Spinach 6 Types of Balls: Fish Ball, Beef Ball, Sotong Ball, Crab Ball, Lobster Ball, Fish Cake Live Char Kway Teow, Yellow Mee Live Cooking Station Stall Pisang Goreng, Keledek Goreng, Cucur Sayur Spring Roll, Samosa, Keropok Lekor, Keladi Goreng Roti Jala Pandan Kuah Durian Chicken Satay & Beef Satay with Condiment Indian Roti Canai, Mini Murtabak Served -

Food KL 1 / 100 Nasi Lemak

Food KL 1 / 100 Nasi Lemak ● Nasi Lemak is the national dish of Malaysia. The name (directly translated to ‘Fatty Rice’) derives from the rich flavours of the rice, which is infused in coconut milk and pandan. ● The rice is served with condiments such as a spicy sambal, deep fried anchovies and peanuts, plus slices of raw cucumbers and boiled eggs. Photo credit: http://seasiaeats.com/ Food KL 2 / 100 Food KL 3 / 100 Roti Canai ● Roti Canai is a local staple in the Mamak (Muslim Indian) cuisine. ● This flat bread is pastry-like and is somehow crispy, fluffy and chewy at the same time. ● It is usually served with dhal and different types of curries. Photo credit: http://kuali.com/ Food KL 4 / 100 Food KL 5 / 100 Teh Tarik ● There is nothing more comforting thnt a hot glass of sweet teh tarik (pulled tea). ● Black tea is mixed with condensed milk and “pulled” multiple times into frothy perfection. ● You can order it plain or ask for teh tarik halia, which has ginger. Photo credit: http://blog4foods.wordpress.com/ Food KL 6 / 100 Food KL 7 / 100 Ikan Bakar ● Directly translated to English, Ikan Bakar means burnt fish. ● Whole fish or sliced fish is slathered with a sambal or tumeric paste and is charcoal-grilled or barbequed (sometimes in a banana leaf wrap). ● It is often served with a soy-based dipping sauce that brings out the flavours even more. Food KL 8 / 100 Food KL 9 / 100 Banana Leaf Rice ● In traditional South Indian Cuisine, a meal is normally served on a banana leaf. -

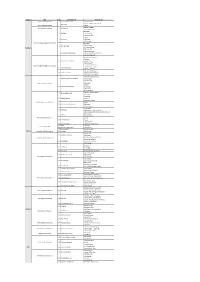

Attachment 1

Region RSA No Stall Operator Type of Food Gurun RSA Northbound 1 Chicken Rice Corner - Set Nasi Ayam - Nasi Lemak Ayam Berempah 2 Wan Laksa Gurun RSA Southbound - Laksa - Set Asam Pedas Juru Layby Southbound 3 Saji Penang - Nasi Ayam Penyet Beverages 4 One Teko - Sirap Selasih - Ice Lemon Tea - Laksa 5 Raja Ulam - Nasi Bajet - Nasi Lemak RSA Gunung Semanggol Northbound Beverages 6 Teh Tarik Cafe - Teh Ais Cincau - Air Mata Kucing Northern - Teh Hijau Ais - Nasi Lemak Ayam 7 Nasi Lemak & Aneka Sup - Nasi Lemak Sambal Sotong - Nasi Goreng Ayam - Burger Ayam/Daging - Samosa 8 Adamira Seven Delights - Roti Hotdog - Keropok Lekor - Sausage Jumbo Cheese RSA Gunung Semanggol Southbound - Set Roti Bakar + Kopi 9 Transit Minuman - Set Pau + Teh Tarik - Set Latte + Chipsmore 10 Two Cups Coffee - Set Mocha + Chipsmore - Set Frappe + Chipsmore - Mi Sizzling Ayam/Daging 11 Sizzling Claypot & Ikan Bakar - Nasi Claypot - Yong Tau Foo RSA Tapah Southbound - Nasi Ayam - Mi Kari 12 Selera Utara Ikan Bakar - Bihun Sup - Mi Goreng - Bihun Goreng - Set Pau + Mineral Water 13 Tanjung Malim Pau - Frozen Pau - Mi Udang 14 Aneka Citarasa - Mi Rebus - Nasi Ayam Penyet RSA Ulu Bernam Southbound - Mi Kari 15 D’Famous Dzul Mee Kari - Nai Ayam - Laksa Penang - Kuih Apam 16 Café Sinar - Set Sandwic + Teh Cincau Ais - Set Puding Custard Cocktail + Teh Hijau Ais - Pau Variety 17 Yik Mun - Hainan Coffee RSA Rawang Northbound - Bread 18 Harolds Bread - Pastry - cakes varieties 19 Speedway Mart Convenient Shop, Snacks 20 A&W Burger Set Sungai Buloh OBR 21 Sate Kajang Hj -

Daftar Sentra Industri Kecil Menengah Hingga Tahun 2016 72,113 167,579 192,257,762 1,648,544,665 919,937,816 Alamat Uu Tk N Investasi Kap

DAFTAR SENTRA INDUSTRI KECIL MENENGAH HINGGA TAHUN 2016 72,113 167,579 192,257,762 1,648,544,665 919,937,816 ALAMAT UU TK N INVESTASI KAP. PRODUKSI N PRODUKSI NILAI BB/BP PIJAR Kode NO. NAMA SENTRA TAHUN DESA/ KELURAHAN KECAMATAN KOTA (UNIT) (ORANG) (RP.000) JUMLAH SATUAN (RP.000) (RP.000) Sektor S J R 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 Abon Tanjung Karang Sekarbela Mataram 1 5 15,000 6,000 Kg 840,000 550,200 1 2,016 s 2 Abon Cakranegara Selatan Cakranegara Mataram 2 5 4,000 12,000 Kg 1,680,000 1,100,400 1 2,016 s 3 Abon Ampenan Tengah Ampenan Mataram 1 2 20,000 720 Kg 100,800 66,024 1 2,016 s 4 Abon Bintaro Ampenan Mataram 1 3 1,000 900 Kg 126,000 82,530 1 2,016 s 5 Abon Lele Tanjung Karang Sekarbela Mataram 5 10 16,000 1,500 Kg 150,000 98,250 1 2,016 6 Aneka Pangan(Bawang Goreng) Selagalas Sandubaya Mataram 3 5 8,500 900 Kg 6,300 4,127 1 2,016 7 Aneka Pangan (Es Krim) Jempong Baru Sekarbela Mataram 2 40 60,000 60,000 Kg 1,200,000 786,000 1 2,016 S 8 Aneka Pangan (Jamur) Mataram Timur Mataram Mataram 1 2 10,000 1,500 Kg 37,500 24,563 1 2,016 9 Aneka Pangan (Es Krim) Pejanggik Mataram Mataram 1 2 3,000 400 Kg 8,000 5,240 1 2,016 S 10 Aneka olahan kacang Pagesangan Timur Mataram Mataram 4 8 12,000 1,200 Kg 90,000 58,950 1 2,016 11 Bakso Pagutan Barat Mataram Mataram 1 2 10,000 1,800 Kg 126,000 82,530 1 2,016 s 12 Bakso Bintaro Ampenan Mataram 2 8 2,000 3,000 Kg 210,000 137,550 1 2,016 s 13 Dodol Monjok Barat Selaparang Mataram 2 6 33,000 54,000 Kg 4,050,000 2,652,750 1 2,016 14 Dodol Sapta Marga Cakranegara Mataram 2 7 27,000 -

Senarai Kilang Dan Pembuat Makanan Yang Telah Mendapat Sijil Halal

SENARAI KILANG DAN PEMBUAT MAKANAN YANG TELAH MENDAPAT SIJIL HALAL DAERAH NO KILANG / PEMBUAT MAKANAN Belait 1. Ferre Cake House Block 4B, 100:5 Kompleks Perindusterian Jalan Setia Diraja, Kuala Belait. Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 ponge Cake 2 ed Bean B skuit 3 ed Bean Mini Bun 4 utter Mini Bun 5 uger Bun 6 ot Dog Bun 7 ta Bread 8 offee Meal Bread 9 andwich Loaf 10 Keropok Lekor 11 urry Puff Pastry 12 Curry Puff Filling 13 onut 14 oty B oy/ R oti Boy 15 Noty Boy/ Roti Boy Topping 16 eropok Lekor kering 17 os K eropok Lekor 18 heese Bun Jumlah Produk : 18 2. Perusahaan Shida Dan Keluarga Block 4, B2 Light Industry, Kuala Belait KA 1931 Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 Mee Kuning 2 Kolo Mee 3 Kuew Tiau 4 Tauhu Jumlah Produk : 4 Hak Milik Bahagian Kawalan Makanan Halal, Jabatan Hal Ehwal Syariah, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama, Negara Brunei Darussalam 26 August, 2014 Page 1 of 47 DAERAH NO KILANG / PEMBUAT MAKANAN 3. Syarikat Hajah Saibah Haji Hassan Dan Anak-Anak Block 4 No B6 Kompleks Perindustrian Pekan Belait,Kuala Belait Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 Mee Kuning 2 Kuew Teow 3 Kolo Mee Jumlah Produk : 3 4. Syarikat Hajah Saibah Haji Hassan Dan Anak-Anak Block 4B No 6 Tingkat Bawah,Kompleks Perindustrian Pekan Belait,Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 Karipap Ayam 2 Karipap Daging 3 Karipap Sayur 4 Popia Ayam 5 Popia Daging 6 Popia Sayur 7 Samosa Ayam 8 Samosa Daging 9 Samosa Sayur 10 Onde Onde 11 Pulut Panggang Udang 12 Pulut Panggang Daging 13 Kelupis Kosong Jumlah Produk : 13 Brunei-Muara Hak Milik Bahagian Kawalan Makanan Halal, Jabatan Hal Ehwal Syariah, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama, Negara Brunei Darussalam 26 August, 2014 Page 2 of 47 DAERAH NO KILANG / PEMBUAT MAKANAN 1. -

PREPARED by ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS DEPARTMENT for Further Enquiries, Please Contact Customs Call Center

PREPARED BY ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS DEPARTMENT For further enquiries, please contact Customs Call Center : 1 300 88 8500 (General Enquiries) Operation Hours Monday - Friday (8.30 a.m – 7.00 p.m) email: [email protected] For classification purposes please refer to Technical Services Department. This Guide merely serves as information. Please refer to Sales Tax (Goods Exempted From Tax) Order 2018 and Sales Tax (Rates of Tax) Order 2018. Page 2 of 130 NAME OF GOODS HEADING CHAPTER EXEMPTED 5% 10% Live Animals (Subject to an import/export license from the relevant authorities) Live Bee (Lebah) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Boar (Babi Hutan) 01.03 01 ✔ Live Buffalo (Kerbau) 01.02 01 ✔ Live Camel (Unta) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Cat (Kucing) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Chicken (Ayam) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Cow (Lembu) 01.02 01 ✔ Live Deer (Rusa) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Dog (Anjing) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Duck (Itik) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Elephant (Gajah) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Frog (Katak) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Geese (Angsa) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Goat (Kambing) 01.04 01 ✔ Live Horse (Kuda) 01.01 01 ✔ Live Oxen 01.02 01 ✔ Live Pig 01.03 01 ✔ Live Quail (Puyuh) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Rabbit (Arnab) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Sheep (Biri-biri) 01.04 01 ✔ Live Turkey (Ayam Belanda) 01.05 01 ✔ Meat & Edible Meat Offal (Subject to an import/export license from the relevant authorities) Beef Bone (Tulang Lembu) (Fresh/ Chilled) 02.01 02 ✔ Beef Bone (Tulang Lembu) (Frozen) 02.02 02 ✔ Belly (Of Pig) (Fresh/ Chilled/ Frozen) 02.03 02 ✔ Boneless Ham (Of Pig) (Fresh/ Chilled/ 02.03 02 ✔ Frozen) This Guide merely serves as information. -

Keropok Lekor’ Process

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.27, 2015 The Authentic of ‘Keropok Lekor’ Process Wan Nur Nai’mah Wan Md. Hatta Bachelor of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai 81310, Johor, Malaysia Abstract This paper attempts to study the authentic of ‘Keropok Lekor’ making process where this is one of the heritage value that should be preserved and documented. The making process of ‘Keropok Lekor’ is documented in five main steps which are preparing fish flesh, preparing dough, kneading and rolling, boiling and cooking. The making process was documented in details the traditional and new way of process. The study of this culture will be one of the factors that will be considered in designing spaces for the ‘Rumah Lekor Setiu’. The material used and the characteristics of ingredients have been generated the culture of making process. Keywords : ‘ Keropok Lekor’; traditional snack of Terengganu; fish fritter or fish sausage which is chewy one. Introduction In Malaysia every state has their own unique and specialty of traditional food. Nur Khaizura (2010) said ‘Keropok Lekor’ is one of traditional snacks and a heritage of Terengganu. It is already famous as snacks since before it is commercialized a few decades ago. Until todays, the culture of ‘ Keropok Lekor’ already spreads around the country. The traditional foods are strongly related with the local ingredients in a local production with using the knowledge of local people. Local gastronomy which is part of cultural heritage becoming one of the most popular forms of tourism and is highly demanded (Lopez and Martin, 2006).