CHAPTER 3 the IMPERIAL SCOURGES Cholera, Malaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answered On:31.07.2000 Buildings for Post Offices Baliram

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA COMMUNICATIONS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1258 ANSWERED ON:31.07.2000 BUILDINGS FOR POST OFFICES BALIRAM Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: (a) the details of post offices functioning in rented buildings particularly in Azamgarh and Mau districts of U.P. and Mumbai in Maharashtra, district-wise; (b) the amount paid by the Government as rent for these buildings during 1999-2000; (c) whether the Government propose to construct departmental buildings for the post offices at those places; (d) if so, the details thereof, district-wise; and (e) if not, the reasons therefor? Answer MINISTER OF STATE FOR COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI TAPAN SIKDAR): (a) There are a total of 2599 post offices functioning in rented buildings in U.P. and 228 post offices functioning in rented buildings in Mumbai city. Details of the post offices functioning in rented buildings particularly in Azamgarh and Mau district of U.P. and Mumbai in Maharashtra is given district wise at Annexure `A`. (b) The amount paid by the Government as rent for these rented buildings is given at Annexure `B`. (c) There is no immediate proposal for construction of departmental buildings at place mentioned in (a) above. (d)&(e) No reply called for in view of (c) above. STATEMENT IN RESPECT OF PART (a) & (b) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1258 FOR 31ST JULY, 2000 REGARDING BUILDINGS FOR POST OFFICES. ANNEXURE `A` (a) The details of post offices functioning in Azamgarh districts, district wise is as follows: Ahraula, Ambari, Atraulia, Azamgarh -

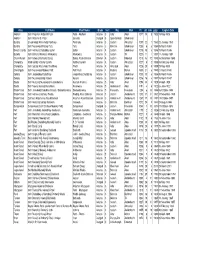

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Beyond Empire and Nation (CS6)-2012.Indd 1 11-09-12 16:57 BEYOND EMPIRE and N ATION This Monograph Is a Publication of the Research Programme ‘Indonesia Across Orders

ISBN 978-90-6718-289-8 ISBN 978-90-6718-289-8 9 789067 182898 9 789067 182898 Beyond empire and nation (CS6)-2012.indd 1 11-09-12 16:57 BEYOND EMPIRE AND N ATION This monograph is a publication of the research programme ‘Indonesia across Orders. The reorganization of Indonesian society.’ The programme was realized by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) and was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Published in this series by Boom, Amsterdam: - Hans Meijer, with the assistance of Margaret Leidelmeijer, Indische rekening; Indië, Nederland en de backpay-kwestie 1945-2005 (2005) - Peter Keppy, Sporen van vernieling; Oorlogsschade, roof en rechtsherstel in Indonesië 1940-1957 (2006) - Els Bogaerts en Remco Raben (eds), Van Indië tot Indonesië (2007) - Marije Plomp, De gentleman bandiet; Verhalen uit het leven en de literatuur, Nederlands-Indië/ Indonesië 1930-1960 (2008) - Remco Raben, De lange dekolonisatie van Indonesië (forthcoming) Published in this series by KITLV Press, Leiden: - J. Thomas Lindblad, Bridges to new business; The economic decolonization of Indonesia (2008) - Freek Colombijn, with the assistance of Martine Barwegen, Under construction; The politics of urban space and housing during the decolonization of Indonesia, 1930-1960 (2010) - Peter Keppy, The politics of redress; war damage compensation and restitution in Indonesia and the Philippines, 1940-1957 (2010) - J. Thomas Lindblad and Peter Post (eds), Indonesian economic decolonization in regional and international perspective (2009) In the same series will be published: - Robert Bridson Cribb, The origins of massacre in modern Indonesia; Legal orders, states of mind and reservoirs of violence, 1900-1965 - Ratna Saptari en Erwiza Erman (ed.), Menggapai keadilan; Politik dan pengalaman buruh dalam proses dekolonisasi, 1930-1965 - Bambang Purwanto et al. -

Heritage List

LISTING GRADING OF HERITAGE BUILDINGS PRECINCTS IN MUMBAI Task II: Review of Sr. No. 317-632 of Heritage Regulation Sr. No. Name of Monuments, Value State of Buildings, Precincts Classification Preservation Typology Location Ownership Usage Special Features Date Existing Grade Proposed Grade Photograph 317Zaoba House Building Jagananth Private Residential Not applicable as the Not applicable as Not applicable as Not applicable as Deleted Deleted Shankersheth Marg, original building has been the original the original the original Kalbadevi demoilshed and is being building has been building has been building has been rebuilt. demoilshed and is demoilshed and is demoilshed and is being rebuilt. being rebuilt. being rebuilt. 318Zaoba Ram Mandir Building Jagananth Trust Religious Vernacular temple 1910 A(arc), B(des), Good III III Shankersheth Marg, architecture.Part of building A(cul), C(seh) Kalbadevi in stone.Balconies and staircases at the upper level in timber. Decorative features & Stucco carvings 319 Zaoba Wadi Precinct Precinct Along Jagannath Private Mixed Most features already Late 19th century Not applicable as Poor Deleted Deleted Shankershet Marg , (Residential & altered, except buildings and early 20th the precinct has Kalbadevi Commercial) along J. S. Marg century lost its architectural and urban merit 320 Nagindas Mansion Building At the intersection Private (Nagindas Mixed Indo Edwardian hybrid style 19th Century A(arc), B(des), Fair II A III of Dadasaheb Purushottam Patel) (Residential & with vernacular features like B(per), E, G(grp) Bhadkamkar Marg Commercial) balconies combined with & Jagannath Art Deco design elements Shankersheth & Neo Classical stucco Road, Girgaum work 321Jama Masjid Building Janjikar Street, Trust Religious Built on a natural water 1802 A(arc), A(cul), Good II A II A Near Sheikh Menon (Jama Masjid of (Muslim) source, displays Islamic B(per), B(des),E, Street Bombay Trust) architectural style. -

Mumbai's Open Spaces Data

MUMBAI’S OPEN SPACES Maps & A Preliminary Listing Document Prepared by Contents Introduction........................................................2 H(W) ward........................................................54 Mumbai's Open Spaces Data..............................4 K(E) ward.........................................................60 Mumbai's Open Spaces Map...............................5 K(W) ward........................................................66 Mumbai's Wards Map..........................................7 P(N) ward.........................................................72 P(S) ward.........................................................78 City - Maps & Open Spaces List ----------------------------------------------------------------- R(N) ward.........................................................84 A ward................................................................8 R(C) ward.........................................................90 B ward..............................................................12 R(S) ward.........................................................96 C ward..............................................................16 D ward..............................................................20 Central & Eastern - Maps & Open Spaces List ----------------------------------------------------------------- E ward..............................................................24 L ward............................................................100 F(N) ward.........................................................30 -

A Top 895 Defaulters Sept 08

LIST OF TOP 895( DEFAULTERS ) ACCOUNTS BILLED IN BILLING MONTH OF JULY 2008 AND NOT PAID TILL 10-09-2008 BALANCE SR. ACCNO NAME ADDR1 ADDR2 NO. ARREARS AS ON 10-09-2008 507036001 4851866.73 REGISTRAR,CITYCIVILCOURTB,BAYOLD. SECRETARIATANNEX.B,BAY400032 CIVIL SECRETARIAT ANNEXE 1 2 507036003 4268561.20 REGISTRAR,CITYCIVILCOURTB,BAYG TO 3 FL OLD SECRETARIATE BLDGFORT 400001B BAY SEPARATE DEPT 3 200011025 3373778.83 DY ENGR WORLI ELECT SUB DIVNG TO 4 FL TRAFFIC CONTROL BRANCHSIR POCHKHANA WALA RD 400025 4 685670001 3138803.58 M/S ROYAL CO INDIA TURF CLUBDR E MOSES RD OPP J CEMENTARY MAHALAXMI 400034 5 200007497 2969772.26 VINAYAKA SYNTHETIES LTD. 3RD FL SHOP-306 JOCANI IND EST J R BORICHA MG L PAREL 400011 6 703519001 2849339.79 WALMIT WOOD WORKS. GRDFL.SAWMILL.COR OF GHORUPDEO X RD.NO.3,4.B,BAY400010. 7 102586000 2599424.15 FIROZ AND COMPANY, GR. TO 1'ST FLOOR,BPT BLDG.G 169/170 , SASOON DOCK, COLABA 8 200010353 2281246.66 M/S P.PULVERSING MILLS, PLOT NO.4 MESSENT RD SEWREE EAST 400015 9 200024673 2218301.93 ABHAYRAJ SINGH KOHLI GR FLR,R.21,DHARMA PUTRA,DR.AMBEDK AR RD,DADAR MUMBAI 400014 10 200002323 2117818.24 THE SUPDT.ARTHUR RD.JAIL. ARTHUR RD, 400011 11 507134003 2103688.12 UPPER POLICE MAHASANCHALAK OLD CUSTOM HOUSE D D BUILDING 4TH FLOOR MUMBAI 12 738680001 2084242.01 DY.ENGG.HSG.ELECT.SUB.DIVN.V 0 0 + 7 TRANSIT CAMP 0 SION(E) PR- ATEEKSHA NAGAR-022 13 100007671 2070604.29 THE DEAN GRANT MEDICAL COLLEGE GRD & 6 UP & BASEMENT, 300 BOYS STUDENT HOSTEL J J HOSP. -

List of Mumbai Agiaries and Atash Behrams

Area Full Name Short Name GradeSect Roj Mah Yz.ddmmyyyy English Date Andheri Seth Pirojshah Ardeshir Patel Patel - Andheri Adaran S Adar Adar 1277 19 5 190819-May-1908 Andheri Seth Ardeshir B. Patel Salsette Dadgah S Spendarmad Shehrevar Bandra Ervad Adarji Kharshedji Panthaky Panthaky Adaran S Sarosh Amardad 1299 22 1 193022-January-1930 Bandra Seth Naserwanji Ratanji Tata Tata Adaran S Behram Shehrevar 1253 6 3 188406-March-1884 Breach Candy Seth Hormusji Dadabhoy Saher Saher Adaran K Sarosh Shehrevar 1215 15 3 184615-March-1846 Byculla Seth Bomanji Merwanji Mewawala Mewawala Adaran S Sarosh Tir 1220 11 1 185111-January-1851 Charni Road Seth Cowasji Behramji Banaji Banaji Atash Behram Behram K Sarosh Khordad 1215 13 12 184513-December-1845 Chowpatty Modi Sorabji Vatcha Gandhi Vatcha Gandhi Adaran K Sarosh Amardad 1227 8 2 185808-February-1858 Chowpatty Seth Sorabji Kharshedji Thoothina Thuthi Adaran K Amardad Adar 1228 29 5 185929-May-1859 Churchgate Seth Naserwanji Manekji Petit Petit Fasli Adaran F Rashne Meher 1309 21 3 194021-March-1940 Colaba Seth Jeejeebhoy Dadabhoy Jeejeebhoy Dadabhoy Adaran S Sarosh Shehrevar 1205 15 3 183615-March-1836 Colaba Seth Nuserwanji Hirji Karani Karani Adaran S Behram Shehrevar 1216 16 3 184716-March-1847 Dadar Seth Rustamji Nuserwanji Rustomframna Rustam Framna Adaran S Adar Avan 1298 14 4 192914-April-1929 Dadar Seth Navroji Kavasji Narielwala Narielwala Adaran S Ardibehesht Adar 1191 3 6 182203-June-1822 Dhobi Talao Seth Jamshedji Dadabhai Amaria / Sodawaterwala Sodawaterwala Adaran S Fravardin -

Akshay Shetty 022-65619181 T 19&20, 3Rd Floor, Ripplez Mall, Plot

Akshay Shetty 022-65619181 T 19&20, 3rd Floor, Ripplez Mall, Plot No.6A, Sector-7, Airoli, Next to Dominoz Pizza, Navi Mumbai – 400708, Maharashtra [email protected] Jaipal K Narang 0251-2721884 0251-2721884 Gurudev, Plot No. 16, Ground Floor, Near Ambernath Station, District Thane, Ambernath, Dist. Thane, Mumbai, Maharshtra [email protected] Ashish Bafna 022-28389245 022-28389207 1st Floor, Harshad Smruti, Old Nagardas Road Andheri (East), Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Susmitha 022-66949404 022-65212126 022-65216521 Nadco Shopping Complex, Andheri West, Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Odette P D Silva 022-26430756 022-26434493 2nd Floor, Guru Vidya CHS, Hill Road, Near Police Station, Bandra (W), Mumbai – 400050 98-A Hill Road, Bandra (West), Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Charushila Prakash Birje 022-2166222 022-21660223 No. 327/328, 1st Floor, Dreams Mall, Station Road, Near Bhandup Railway Station, Bhandup, Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Pranjali Balkrishna Shetye 022-28901645 022-28904105 2nd Floor, Bhandarkar Bhavan, Near Police Station, Borivali (W), Mumbai – 400025 Opp. Railway Station, Borivli (West), Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Pooja Sawant 022-22042442 022-22042446 022-22042449 3rd floor, Express Bldg, Above Satkar Hotel, Opp. Churchgate Rly. Station, Churchgate, Mumbai – 400020 [email protected] Ashish Bafna N / A 413 Sun Shine Plaza, 4th Floor Naigaum Cross Road, Dadar (East), Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Jaipal K. Narang 022-24376897 022-24221372 201 & 202, Apple Plaza, Next to Dadar Manish Market, Near Railway Station, Dadar West, Mumbai, Maharashtra [email protected] Jaipal K Narang 0251-2861589 0251-2861825 2nd floor, Commerce Centre, Opp. -

Open Spaces & Water Bodies in Greater Mumbai

Inventorisation of Open spaces & Water Bodies in Greater Mumbai PREFACE Mumbai, the largest metropolis of India and the third largest in the world, is a unique city. It enjoys both, a dense and multi cultural demographic diversity as well as a varied range of environmental features. There are rivers, natural drains, lakes, hills, forests and coastal features like beaches, rocky outcrops, mangroves and creeks. However, growth in population and changes in the State policies, in the past few decades has resulted in phenomenal construction activity adversely affecting all the environmental features. While the natural water bodies are fast disappearing through negligence, and uncontrolled development, the open spaces meant for recreation and sports are grossly inadequate, both in their numbers and in their areas, to address the bare minimum needs of Mumbai’s growing population. The Open Spaces, marked as Reservations on the Development Plan of Greater Mumbai, as Recreational Grounds, Play Grounds, Gardens etc, account for only 6% of the land area. On the other hand the locations of the existing water bodies are not even indicated on the Development Plan. This Development Plan was prepared in the 1980s, for which the survey was undertaken in 1980. Needless to say, that the ground reality of these reservations, after 30 years, is enormously different. The current reality therefore needs to be thoroughly examined on two levels: a) with respect to their deficiency and b) with respect to their current status and conditions. Only after such an assessment that an appropriate strategy can be devised; a strategy which will ensure the provision of Open Spaces that are both, adequate and accessible to all. -

Maharashtra Council of Homoeopathy 235, Peninsula House, Above Sbbj Bank, 3Rd Floor, Dr

MAHARASHTRA COUNCIL OF HOMOEOPATHY 235, PENINSULA HOUSE, ABOVE SBBJ BANK, 3RD FLOOR, DR. D.N. ROAD, FORT, MUMBAI- 400001 MAHARASHTRA STATE HOMOEOPATHY PRACTITIONER LIST Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. EMAIL ID Remarks 1 CHUGHA TEJBHAN B 9/27, KRISHNA NAGAR Male DEFAULTER GOPALDAS P.O.GANDHI NAGAR, DELHI-51 NAME REMOVED DELHI DELHI 2 ATHALYE VASUDEO 179, BHAWANI PETH Male DEFAULTER VISHVANATH SARASWATI SADAN NAME REMOVED SATARA MAHARASHTRA 3 KUNDERT ABRAHAM 2,RAVINDRA BHUVAN DR. Male DEFAULTER CHANDRASHEKARA AMBEDKAR ROAD,KHAR NAME REMOVED 400052 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 4 PINTO LAWRENCE 22/23 IBRAHIM COURT ST.PAUL Male DEFAULTER MARTIN BALTAZAR ST.NAIGAUM DADAR, NAME REMOVED 400014 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 5 CHUGHA CAMP 180, SHREE NAGAR Male DEFAULTER PRAKASHCHANDRA COLONY INDORE I.M.P. PRAKASHCHANDRA COLONY INDORE I.M.P. NAME REMOVED BHANJANRAM MADHYA PRADESH 6 SHAIKH MEHBOOB ABBAS CHAKAN,TALUKA-KHED Male DEFAULTER NAME REMOVED PUNE MAHARASHTRA 7 PARANJPE MORESHWAR 1398,SADASHIV PETH, POONA Male DEFAULTER NARAYAN NAME REMOVED PUNE MAHARASHTRA 8 CAPTAIN COWAS CAPTAIN VILLA,4, BANDRA HILL, Male DEFAULTER CURSETJI MT.MARY RD NAME REMOVED MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 9 GUPTA KANTILAL C/O DR.P.C.CHUGHA RAVAL Male DEFAULTER SOHANLAL BLDG.LAMINGTON RD NAME REMOVED 400007 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 10 MENDONCA BLANCHEDE 19,ST.FRANCIS AVENUE, Female DEFAULTER WELLINGDON SOUTH NAME REMOVED SANTACRUZ, 400054 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 11 HATTERIA HOMEE SIR.SHAPURJI BHARUCHA BAUG Male DEFAULTER ARDESHIR SORABJI PLOT NO.L, FLAT NO.4 NAME REMOVED GHODBUNDER -

In the Service of the Sacred Developmentfor Conservation by Kozhikode B/Oy Ramachandran Bachelor in Architecture B.M.S

In the Service of the Sacred Developmentfor Conservation by KoZhikode B/oy Ramachandran Bachelor in Architecture B.M.S. College of Engineering Bangalore, India February, 1995 Submitted to the Department ofArchitecture in partialfufillmentof the requirementsforthe degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June, 1998 @ KorZhikode B/oy Ramachandran 1998. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to M.IT. permission to reproduce and distributepublicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of the Author KoiZhikode B/oy 3ofachandran Department Architecture June, 1998 Certified by - Julian Beinart v \j Professor ofArchitecture Thesis Co-Advisor Certified by Attilio Petruccioli Visiting Associate Professor Aga Khan Professor of Designfor Islamic Culture Thesis Co-Advisor Accepted by\ Roy Strickland Associate Professor ofArchitecture Chairman, Department Committee on GraduateStudents In the Senice of Ihe Saced 1 L!BiM -E - 3 StanfordAnderson Professor ofHistory andArchitecture Head of Department Reader In the Senice of/the Sacred Suni Mummy & Pappa & Prem In the Senice of/the Sacred Contents Acknowledgements 5 Abstract 6 Introduction 9 Part One A ColonialEnterprise From the Portuguese(1509) to The Port Trust (1873) 11 Part Two Banganga: Religious Core Existing Conditions & Challenges 25 Part Three PreservingA Legay The HeritageAdvisory Committee & Drawing Precinct Boundaries 31 Part Four Developmentfor Conservation Opportunities &Design interventions 36 PartFive Conclusions 44 Appendix Maps 46 Bibliography Illustration Credits In the Service of the Sacred A cknowledgements Thanks to Harshad Bhatia, for his wonderful Master's thesis project on Banganga, and his constant support all through, Prof. Julian Beinart, for making me think beyond good drawings and towards application, Prof. -

Zl HI\Lt,F, KM8F,F, XFC

SHRI MAHAVIRA JAINA VIDYALYA – JINALAYA TRUST CANDIDATES zL HI\lT,F, KM8F,F, XFC lX1F6o ALP SMD s;LPV[PVF.PVF.PALPf E}T5}J" lJnFYL" o zL DCFJLZ H{G lJnF,I4 J0MNZF XFBF zL DCFJLZ H{G lJnF,I v lHGF,I 8=:8L zL DCFJLZ H{G lJnF,I4 V\W[ZL XFBFo E}T5}J" DFG¡ D\+LzL CF,DF\ V\W[ZL XFBFGF :YFlGS SlD8LGF ;eIzL zL V\W[ZL U]HZFTL H{G ;\Ws .,F" A|LHfGF 8=:8L cE~R Ò,FGF ,F0 zLDF/L `J[TF\AZ D}lT"5}HS H{G ;\Wcc v 5|D]B ——lR\TG˜˜ ;\:YFGF v SlD8L ;eI Shri Jaysukhlal Mavjibhai Shah (Tanawala) Bhavnagar, Andheri Shree Bhavnagar Jain Shewatambar Murtipujak Tapasangh, Bhavnagar. Vice president (UPPRAMUKH) Shree Krishnnagar Jain Society Bhavnagar President (PRAMUKH) Shree Tana Jain Sangh (Trustee) Sheth Shree Aanadji Kalyanji Pedhi, Ahmadabad Pra. Trustee Shree Jeshalmer Tirth Trustee Shree Swami Narayan Gurukul, Bhavnagar Secretary (Mantri) Shree Bhavnagar Panjarapol, Trustee Shri Pankanj Chimanlal Diora Birth Date: 06/09/1953 Past Student of Bhavnagar Branch Local Committee Member of Sandhurst Road Branch Navraji Lane, Ghatkopar (W), Jinalaya’ s Kothari and Member Trustee of Omkar Tirth Shri Palitana Ghoghari Vishashrimali Jain Samaj (Mumbai)- Hon. Secretary Shri Yashovijayji Jain Gurukul- Palitana Committee Member Having own Gruh Jin Mandir Economic support to Religious projects, Helping in Vaiyayachha. SHRI MAHAVIRA JAINA VIDYALYA – JINAGAM PRAKASHAN TRUST CANDIDATES Kishor Gopalji Sheth Age: 60. Mobile: 9820020137 Email: [email protected] In Business of Corporate Finance Past President Shri Mahavir Jain Vidyalaya Alumni Association, Committee member Shri Mahavir Jain Vidyalaya Andheri Branch., Office Bearer in Palitana Jain Sangh.