Whitefella Jump Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles and Books About Western and Some of Central Nsw

Rusheen’s Website: www.rusheensweb.com ARTICLES AND BOOKS ABOUT WESTERN AND SOME OF CENTRAL NSW. RUSHEEN CRAIG October 2012. Last updated: 20 March 2013 Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig Using the information from this document: Please note that the research on this web site is freely provided for personal use only. Site users have the author's permission to utilise this information in personal research, but any use of information and/or data in part or in full for republication in any printed or electronic format (regardless of commercial, non-commercial and/or academic purpose) must be attributed in full to Rusheen Craig. All rights reserved by Rusheen Craig. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Wentworth Combined Land Sales Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig 1 Contents THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE WESTERN PLAINS. ...................................................... 6 Exploration of the Bogan. ................................................................................................................................... 6 Roderick Mitchell on the Darling. ...................................................................................................................... 7 Exploration of the Country between the Lachlan and the Darling ...................................................................... 7 Occupation of the Country. ................................................................................................................................ 8 Occupation -

SOLONEC Shared Lives on Nigena Country

Shared lives on Nigena country: A joint Biography of Katie and Frank Rodriguez, 1944-1994. Jacinta Solonec 20131828 M.A. Edith Cowan University, 2003., B.A. Edith Cowan University, 1994 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (Discipline – History) 2015 Abstract On the 8th of December 1946 Katie Fraser and Frank Rodriguez married in the Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Derby, Western Australia. They spent the next forty-eight years together, living in the West Kimberley and making a home for themselves on Nigena country. These are Katie’s ancestral homelands, far from Frank’s birthplace in Galicia, Spain. This thesis offers an investigation into the social history of a West Kimberley couple and their family, a couple the likes of whom are rarely represented in the history books, who arguably typify the historic multiculturalism of the Kimberley community. Katie and Frank were seemingly ordinary people, who like many others at the time were socially and politically marginalised due to Katie being Aboriginal and Frank being a migrant from a non-English speaking background. Moreover in many respects their shared life experiences encapsulate the history of the Kimberley, and the experiences of many of its people who have been marginalised from history. Their lives were shaped by their shared faith and Katie’s family connections to the Catholic mission at Beagle Bay, the different governmental policies which sought to assimilate them into an Australian way of life, as well as their experiences working in the pastoral industry. -

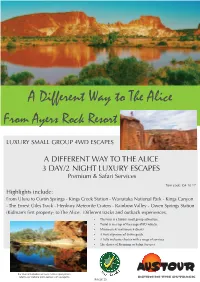

A Different Way to the Alice from Ayers Rock Resort

A Different Way to The Alice From Ayers Rock Resort LUXURY SMALL GROUP 4WD ESCAPES A DIFFERENT WAY TO THE ALICE 3 DAY/2 NIGHT LUXURY ESCAPES Premium & Safari Services Tour code: G4 10 17 Highlights include: From Uluru to Curtin Springs - Kings Creek Station - Warrataka National Park - Kings Canyon - The Ernest Giles Track - Henbury Meteorite Craters - Rainbow Valley - Owen Springs Station (Kidman’s first property) to The Alice. Different tracks and outback experiences. • This tour is a luxury small group adventure. • Travel is in a top of the range 4WD vehicle. • Minimum 4/ maximum 4 clients • A very experienced driver guide • A fully inclusive charter with a range of services • The choice of Premium or Safari Services AUSTOUR For more information on tours in this region please refer to our website www.austour.com.au/agents BORN IN THE OUTBACK PAGE 23 3 DAY/2 NIGHT EXPERIENCE A TRIP INTO NATURE Luxury Small Group 4WD Private Tour Charter Tour code: G4 10 17 Day 1 Ayers Rock to Kings Canyon via Cattle Stations, Salt Lakes & Desert Oak Forest Farewell Uluru – we trust you have enjoyed your stopover and have many wonderful memories of your visit to this wondrous site, the world’s largest monolith. Your first stop is at Curtin Springs Cattle Station for a cuppa and a quick look around the Station Homestead. Other stops along the way will include a photo stop at Attila (Mt Connor), an unusual mountain formation and Lake Amadeus, a huge salt pan. Also you will travel through a unique desert oak forest and perhaps see a dingo or two or wild camels as you journey towards Watarrka National Park and the mighty Kings Canyon. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Ockham's Razor

The Journal of the European Association for Studies of Australia, Vol.4 No.1, 2013. Reading Coolibah’s Story: As told by Coolibah to John Boulton John Boulton Copyright © John Boulton 2013. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract: This paper describes selected key events in the life of Coolibah, a retired Gurindji stockman, through his non-Aboriginal friend John Boulton. Coolibah made John “a close friend of the same age”, referred to specifically as tjimerra in Gooniyandi language (the language that he has become most familiar with since being removed from his family as a small child). This classifactory kin relationship makes it possible for John Boulton to tell Coolibah’s story. This article is situated within the tradition of oral histories of the lives of Aboriginal people at the colonial frontier. It is also within a tradition of friendships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, including European, people, often anthropologists and other professionals with a deep commitment to that world. In this article, Boulton uses the events of Coolibah’s life and that of his family and kin as a departure point to discuss the impact of history on the health of the people. Coolibah’s life is viewed through the lens of structural violence whereby the causal factors for the gap in health outcomes have been laid down. This article provides the theoretical framework to understand the extent of psychic, emotional and physical harm perpetrated on generations of Aboriginal people from the violent collision of the two worlds on the Australian frontier. -

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek Was Declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek was declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985. HISTORY Innamincka and Cooper Creek have a rich history. The area has also been associated with many other facets of the state's history since colonial settlement. Names such as Charles Sturt, Sidney Kidman, Cordillo Downs, the Australian Inland Mission and the Reverend John Flynn are intrinsically woven into the stories of Innamincka and the Cooper Creek. Its significance for Aboriginal people spans thousands of years as a trade route and a source of abundant food and fresh water. The area's Aboriginal history also includes significant contacts with explorers, pastoralists and settlers. Many sources believe that the name 'Innamincka' comes from two Aboriginal words meaning ' your shelter' or 'your home'. European contact with the region came first with the explorers and later with the establishment of the pastoral industry, transport routes and service centres. Cooper Creek was named by Captain Charles Sturt on 13 October 1845, when he crossed the watercourse at a point approximately 24 kilometres west of the current Innamincka township. The water was very low at the time, hence his use of the term 'creek' rather than 'river' to describe what often becomes a deep torrent of water. Charles Cooper, after whom the waterway was named, was a South Australian judge - later Chief Justice Sir Charles Cooper. On the same expedition, Sturt also named the Strzelecki Desert after the eccentric Polish explorer, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, who was the first European to climb and name Mount Kosciusko. -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. 29 ISBN O 86740 357 8 ISSN 0816...,6323 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

2018 September Quarter

Hancock Agriculture September 2018 3, Issue 3 Hancock Kidman Making us the best Cattle Company National Agriculture and Related Industries Day National Agriculture and Related Industries Day will be held again this year on Wednesday 21 November 2018. To all pastoral properties and employees you should start thinking of how we can all start celebrating this important day. Santa Gertrudis and Coolibah Composite bulls in forage oats on Rockybank Staon Inside this issue Naonal Agriculture and Related Industries Day ................1 Wed, 21 November 2018 Message from Your Chairman .....2 Sydney CBD Speech by Mrs Gina Rinehart Reserve your tables or seats AmCham 50th Anniversary Gala now for the annual gala dinner Dinner .........................................4 (Akubras and boots welcome!) [email protected] Message from Your CEO ..............10 Capex / Opex upgrades ...............11 General Manager Updates ..........12 Health and Wellbeing Mental Health Month..................14 Staon News ...............................15 Done Training Courses ................16 Future Important Dates Staff Achievements Hancock Agriculture 2019 recruitment ad ...........................17 Santa Gertrudis cale at S. Kidman & Co Pty Ltd Naryilco Staon, Qld Message from Your Chairman Dear team members I hope you are all doing well and I appreciate the wonderful efforts and commitment that you are making including through the drought – rain is, together with you all, the key to life on staons and farms too. We should see a moratorium on all government fees and charges for at least two years to allow people to recover on the land. Of course this is not the first me I have called for red tape and taxes to be reduced, for instance I refer to this in my speech to AmCham in the newsleer, and why this has been so successful in the USA, as making people more able to get on with business and get out of debt, is much beer than loans which push people further into debt, with interest and me consuming reporng obligaons. -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Helen Ross (Editor) Eileen Bray (translator) East Kimberley Working Paper No. 28 ISSN 0 86740 356 X ISBN 0816-6323 ,.- April 1989 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Helen Ross (Editor) Eileen Bray (translator) East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

Durham Downs — a Pastorale

This is part ofa set Braided Channels Vol 2 Item 4 and may NOT be borrowed separately. Durham Downs — a Pastorale The story of Australia told through the lives of two families, united in their passion for three million acres of land: Durham Downs. 070.18 FITZ [1-2] Concept document produced with the assistance of the Pacific Film and Television Commission and Film Australia. V-------- J > Up* i nfo@jerryca nfi I ms .corn au 32007004706179 PO Box 397 Nth Tambonne Braided channels : QLO 4272 documentary voice from an Ph *61 7 5545 3319 interdiscplinary, Fax +61 7 5545 3349 cross-media, and practitioners's perspective Synopsis Durham Downs - a Pastorale is a 1 x 52 minute documentary that explores the love of land and sense of place that this ancient landscape in far SW Queensland inspires through the story of two families. The film follows the lives of the Ferguson family, retiring managers of Durham Downs Station, as their home passes on to the next family of employees of S. Kidman and Co., the Station’s pastoral lease-holder. As they end a thirty year association with the property and an at least five generations association with the area, the Fergusons are grieving for the loss of their home and trying to make sense of who they will be without Durham Downs. Running in parallel to the Ferguson’s story is that of the Ebsworth family and the Wangkumarra people. Moved from their traditional home in the 1930s, and having worked for the Station over generations, oil and gas exploration of the land is creating new opportunities for them to relate to their land. -

Desert Sky News July 2014.Pub

“It’s All About The Experience – Yours and Ours ” Volume 16 Issue 2 Telephone : 08 8356 1874 July 2014 wo trips in June to Coongie News from around…… Geoff Morgan Gallery Lakes, with the first closely Mungerannie Hawker SA T following a rain band which delivered some reasonable falls to a Many readers will Last October Miriam and number of outback areas. The Strzelecki remember John and Jeff decided to go ahead Track had been closed for a few days Genevieve with another Panorama prior, and I wondered if we would have a Hammond who ran next to the existing repeat of our 2013 trip, where we the Mungerannie Wilpena Panorama. deviated for a day to Arkaroola, waiting Hotel, half way The new one is to be for the Track to open. Fortunately it along the Birdsville almost twice the size as opened on the day of our departure from Track. the original one built just Adelaide, and we had no problems, We have recollections of many happy over 10 years ago . although the Coongie Lakes track visits, and their welcome and help remained closed and there was no particularly in the early days on our It will be of a scene found in the far definite advice as to when it would open. Birdsville trips was greatly appreciated. northern Flinders Ranges at the amazing Arriving in Innamincka, we changed the Wilderness Sanctuary of Arkaroola. itinerary and visited Camp LXV (The ABC Radio South Dig Tree), and local attractions the next Western Queensland has Unlike most panoramas that are usually day. -

Paintings from Warmun ST PAUL St Gallery One 25 September – 23 October 2015

Paintings from Warmun ST PAUL St Gallery One 25 September – 23 October 2015 These paintings all come from artists working in Warmun, a community of about 400 people located 200 kilometres south of Kununurra in the Kimberley region of far north Western Australia. The Warmun Art Centre there was founded by Queenie McKenzie, Madigan Thomas, Hector Jandany, Lena Nyadbi, Betty Carrington and Patrick Mung Mung, members of the contemporary painting movement that began in the mid-1970s. Warmun Art Centre is owned and governed by the Gija people, its income returned to the community. Today some 50 emerging and established Gija artists work there. The works are by Warmun artists Mabel Juli, David Cox, Lena Nyadbi, Churchill Cann, Gordon Barney, Phyllis Thomas and Shirley Purdie. In these paintings the material is the work; they are earth and mineral as well as images. While they are stylistically very different in approach, all share the ochre, charcoal and natural earth pigments that typify contemporary Aboriginal painting in the Kimberley region. Coloured by iron oxide, ochre ranges from subtle yellow to deep red-brown. Mawandu or white ochre (extensively used in Mabel Juli’s work, alongside black ochre) is distinctive to the Kimberley area. This is a naturally occurring white clay that forms deep in the ground along certain riverbeds. Mixing natural pigments with mawandu provides range of colours including lime greens, greys, and a rare pink, all of which are produced at Warmun and traded with art centres across the region. ‘I don’t paint another country, I paint my own’, says Mabel Juli.