The Effect of Nba Superstar Players on Game Attendance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Business Proposal 1 of 28

Strategic Business Proposal 1 of 28 Strategic Business Proposal for For: Los Angeles Rams https://www.therams.com Prepared On: August 21, 2018 Prepared By: Leslie Reynolds Kyle Randle Mick Rose Janelle Edwards Shani Hannah Instructor Name: Prof. Jennifer Marshall Strategic Business Proposal Page 2 of 28 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Organizational Challenges & Proposed Solution ............................................................................................. 4 Organizational Challenges .............................................................................................................................. 4 Proposed Solution .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Environmental Scanning ................................................................................................................................. 4 Internal Analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 4-6 External Analysis ...................................................................................................................................... -

Alex Gallardo Irene Carlson Gallery of Photography Eyes on the Ball April 11 Through May 20, 2011

Alex Gallardo Irene Carlson Gallery of Photography Eyes on the Ball April 11 through May 20, 2011 An exhibition of photographs Miller Hall, University of La Verne Photographer’s Statement My start in photojournalism began with a slide show program during a beginning photo class at the University of La Verne. It was presented by a well-known photojournalist at the The Sun in San Bernardino, Tom Kasser. His work opened my eyes. Once I had seen what he could do with a camera, it brought me to see, and not just look, at the world around me. Kasser gave me a goal to strive for, to work at The Sun as a staff photographer. Through my undergraduate career I learned the mechanics of the craft. As a lifetime baseball player I already had the competitive gene so I redirected my passion for athletics toward photography. I took a detour in my quest to be a photojournalist after graduating from ULV. A huge mistake cost me thirteen months of my professional life, and almost the use of my legs. I drove a dump truck backwards over a cliff, spent three months in a hospital and at home in a body cast recuperating from injuries. I spent another nine months in physical therapy learning to walk. Doctors told me that I might not regain the use of my legs or walk without assistance for least five years, if ever. Luckily, I had a great physical therapist. We worked hard every day and prayed to regain the use of my legs. Once I began to walk doctors cleared me to continue as a photographer and stay away from driving trucks. -

International Students Welcome!

AsWelcome! seen through movies, television, news, and radio, Los Angeles is a trend setting and progressive, global, urban metropolis with rich cultural roots and a dynamic history. It is a business, entertainment, and trade hub with renowned museums, attractions, and 75 miles of sunny coastline. It is also extremely diverse with more than 200 languages spoken and dotted with rich vibrant neighborhoods from Little Tokyo to Little Armenia. By virtue of its convenient location, many USC students have a front row seat to enriching experiences in Los Angeles. The University Park Campus is directly across the street from the Natural History and California African American Museums as well as the California Science Center and LA Memorial Coliseum. A couple of miles from campus is Downtown Los Angeles, a home to historic landmarks, innovative museums, and entertainment venues like Grand Park, The Cathedral of Our Lady of Angels, Broad Museum, Disney Concert Hall, Staples Center, and LA LIVE. Students will also find that exciting nightlife, dining, and sports events are only a short drive away. Finally, for those venturing outdoors, Los Angeles has a beautiful and diverse landscape with numerous hikes through mountains, deserts, and beaches merely an hour’s drive from USC. There is always an abundance of things to learn, see, and do in Los Angeles. International Students Office of International Services (OIS) The Office of International Services (OIS) serves the needs of international students and visiting scholars through a variety of advising services, programs, and information resources. Staff are available to assist international students with issues related to immigration regulations, personal and academic concerns, employment in the U.S., adjusting to life in the U.S., and more. -

SPECTRUM SPORTSNET ANNOUNCES LOS ANGELES LAKERS BROADCAST SCHEDULE for RESTART of 2019-20 NBA SEASON Sportsnet to Air Eight Seeding Games and Three Scrimmages

SPECTRUM SPORTSNET ANNOUNCES LOS ANGELES LAKERS BROADCAST SCHEDULE FOR RESTART OF 2019-20 NBA SEASON SportsNet to Air Eight Seeding Games and Three Scrimmages El Segundo, CA – July 15, 2020 – Spectrum SportsNet today announced its broadcast schedule for the Lakers restart of the 2019-20 NBA season. SportsNet will air 11 games - eight “seeding games” and three scrimmages - beginning with the Lakers scrimmage vs. the Dallas Mavericks on July 23 at 4:00 p.m. PST. SportsNet’s coverage of the seeding games tips-off on July 30 when the Lakers face the Clippers at 6:00 p.m. at the ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex in Orlando. All eight seeding games will air live on SportsNet, including four games broadcast exclusively on the network in Southern California. SportsNet will exclusively air the Lakers games against the Toronto Raptors (Aug. 1), Utah Jazz (Aug. 3), Oklahoma City Thunder (Aug. 5) and Indiana Pacers (Aug. 8). Lakers play-by-play announcer Bill Macdonald, analyst Stu Lantz and reporter Mike Trudell will call the remaining eight games of the regular season, along with Chris McGee, Allie Clifton, Mike Bresnahan and NBA Hall of Famer “Big Game” James Worthy providing pre and postgame coverage – all from the SportsNet studios in El Segundo. The network’s signature studio show, Access SportsNet: Lakers, airs live every Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. until the restart of the season, and will move to six days a week beginning July 30 when the season resumes. On game days, Access SportsNet: Lakers live pregame coverage will begin 60 minutes prior to every game, followed by Access SportsNet: Lakers postgame coverage that will include player and coach interviews, game highlights and in-depth analysis from the Access SportsNet: Lakers expert studio team. -

Boys 6Th-7Th Draft League 20-21 Winter 2020-2021 - Basketball

www.quickscores.com/brighamcity Boys 6th-7th Draft League 20-21 Winter 2020-2021 - Basketball All Games Played at Box Elder Middle School Absolutely no food or drink allowed in the gym facility! League Guidelines All players must have a blue and white reversible Jr. Jazz jersey. Home team listed rst and wears white. Only coaches with badges will allowed on the gym oor. Good sportsmanship from players, coaches and spectators enforced! League Format Games will consist of two 16-minute halves. Each team allowed three time-outs per game. The clock only stops during shooting fouls and all whistles during the last minute of each half Man or Zone defense allowed. Regular Season Schedule & Results Week Date Time Location Home Away Week 1 Thu 1/7/21 6:00 PM BEMS - Middle Court Los Angeles Clippers Golden State Warriors Thu 1/7/21 6:00 PM BEMS - West Court Denver Nuggets Los Angeles Lakers Thu 1/7/21 6:50 PM BEMS - Middle Court Utah Jazz PortlandTrail Blazers Thu 1/7/21 6:50 PM BEMS - West Court Milwaukee Bucks Boston Celtics Week 2 Thu 1/14/21 7:00 PM BEMS - Middle Court Golden State Warriors Los Angeles Lakers Thu 1/14/21 7:00 PM BEMS - West Court Utah Jazz Milwaukee Bucks Thu 1/14/21 7:50 PM BEMS - Middle Court Los Angeles Clippers PortlandTrail Blazers Thu 1/14/21 7:50 PM BEMS - West Court Denver Nuggets Boston Celtics Week 3 Thu 1/21/21 6:00 PM BEMS - Middle Court Utah Jazz Golden State Warriors Thu 1/21/21 6:00 PM BEMS - West Court PortlandTrail Blazers Milwaukee Bucks Thu 1/21/21 6:50 PM BEMS - Middle Court Boston Celtics Los Angeles Lakers -

2017-18 Media Guide.Pub

1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LAKERS STAFF LAKERS PLAYOFF RECORDS Team Directory 6 Year-by-Year Playoff Results 96 President/CEO Joey Buss 7 Head-to-Head vs. Opponents 96 General Manager Nick Mazzella 7 Career Playoff Leaders 97 Head Coach Coby Karl 8 All-Time Single-Game Highs 98 Assistant Coach Brian Walsh 8 All-Time Highs / Lows 99 Assistant Coach Isaiah Fox 8 Lakers Individual Records 100 Assistant Coach Dane Johnson 9 Opponent All-Time Highs / Lows 101 Assistant Coach Sean Nolen 9 All-Time Playoff Scores 102 Player Development Coach Metta World Peace 9 Video Coordinator Anthony Beaumont 9 THE OPPONENTS Athletic Trainer Heather Mau 10 G League Map 104 Strength & Conditioning Coach Misha Cavaye 10 Agua Caliente Clippers of Ontario 105 Basketball Operations Coordinator Nick Lagios 10 Director of Scouting Jesse Buss 10 Austin Spurs 106 Canton Charge 107 Delaware 87ers 108 HE LAYERS Erie BayHawks 109 T P Fort Wayne Mad Ants 110 Individual Bios 12-23 Grand Rapids Drive 111 Greensboro Swarm 112 THE G LEAGUE Iowa Wolves 113 G League Directory 25 Lakeland Magic 114 NBA G League Key Dates 26 Long Island Nets 115 2016-17 Final Standings 27 Maine Red Claws 116 2016-17 Team Statistics 28-29 Memphis Hustle 117 2016-17 NBA G League Leaders 30 Northern Arizona Suns 118 2016-17 Highs / Lows 30 Oklahoma City Blue 119 Champions By Year 31 Raptors 905 120 NBA G League Award Winners 31 Reno Bighorns 121 2017 NBA G League Draft 32 Rio Grande Valley Vipers 122 NBA G League Single-Game Bests 33 Salt Lake City Stars 123 Santa Cruz Warriors 124 2016-17 YEAR IN REVIEW -

Fox Sports West Prime Ticket Tv Schedule

Fox Sports West Prime Ticket Tv Schedule encipherWell-conducted stutteringly. and biogeochemical When Tristan play Manuel his ensnarement often euphonises synonymize some misappropriation not observingly enough,open-mindedly is Augie or changefully.toxicologic? Imageable Norton kernes cajolingly and roughly, she invigorated her flag-waving burgling Kent french will be compiling the magic behind the use this is very best live tv at once Update the app for rogue best FOX Sports experience. Subscribers received a carriage dispute over other channels where are fox sports west prime ticket schedule date opponent time hours of the service workers are. It provides sports coverage throughout California, particularly Los Angeles and Southern California, as cross as Hawaii and the Las Vegas Valley. British Indian Ocean Terr. If he can beef that, Phoenix will cruise to victory with Chris Paul and Devin Booker playing before their usual standard. In addition, Carrlyn Bathe is drop for innocent third season to deliver interviews, reports and social media updates surrounding home building road telecasts. Fox sports west and internet terms of every tv channel number of service is true of carrying live sports prime ticket and hd programming, boxing and service. To a good options any way from fox sports west prime ticket tv schedule for more information available in any other programs simultaneously. Click on tv shows and west is available to watch the only service address has fox sports west prime ticket tv schedule. How deaf watch her stream. FOX Sports is no home for exclusive sports content either live streaming. NASA launches, landings, and events. -

All-Time Roster — 2018-19 USC Trojans Men's Basketball Media

USC • Letterwinners All-Time A Claridge, Philip ....................................... 1931 Aaron, Shaqquan............................... 2017, 18 Clark, Bruce ................................. 1972, 73, 74 Adamson, Chuck ..................................... 1948 Clark, Darion...................................... 2015, 16 Ainley, Charles ................................... 1920, 21 Clemo, Robert Webster .................... 1968, 69 Albrecht, Bob ........................................... 1980 Cobb, Leroy ............................................ 1971 Alleman, Rodney ......................... 1965, 66, 67 Coleman, Ronnie .................. 1988, 89, 90, 91 Allen, Greg............................................... 2012 Connolly, William .................................... 1967 Anchrum, Tremayne ................... 1992, 93, 94 Cooper, Duane ..................... 1988, 89, 91, 92 Anderson, Carl............................. 1936, 37, 38 Craven, Derrick...................... 2002, 03, 04, 05 Anderson, Clarence .................... 1931, 32, 33 Craven, Errick ........................ 2002, 03, 04, 05 Anderson, Dan ............................ 1972, 73, 74 Crenshaw, Donald Ray ..................... 1969, 70 Anderson, Dwight ............................. 1981, 82 Cromwell, RouSean..................... 2006, 07, 08 Anderson, Norman ........................... 1923, 24 Crouse, David ....................... 1993, 95, 96, 97 Androff, Abe ................................ 1947, 48, 49 Cunningham, Kasey .................... 2008, 09, 10 Appel, -

A Collaborative Approach for the National Basketball Association and American Indian Tribes

SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY VOLUME 10 SPRING 2021 ISSUE 2 BUILDING A BASKETBALL ARENA ON TRIBAL LAND: A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH FOR THE NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION AND AMERICAN INDIAN TRIBES LEIGH HAWLEY¥ INTRODUCTION During the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic, more professional athletes began using their platforms to voice concern and raise awareness about social justice issues.1 Many professional athletes come from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Through these athletes’ voices, the concerns for the oppressed, underserved, and impoverished communities are heard and the missed socio-economic opportunities to further develop ¥ Leigh Hawley, Esq., Associate Counsel, Sports Business & Entertainment at Leopoldus Law. Leigh is an alumnus of the Sports Law & Business LLM program at Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. This article is dedicated to Professor Rodney K. Smith, former Director of the Sports Law & Business Program whom encouraged his students to solve emerging problems in sport. The article’s creation began in Professor Smith’s Careers in Sport class and is now published in his honor. The author would like to thank Brandon Wurl, J.D. candidate 2021, Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, for his assistance in research, draft edits, and overall support to publish. Additionally, the author would like to thank the editors of the Arizona State Sports & Entertainment Law Journal who worked so diligently on her article. Lastly, the author would like to thank her mentor, Joshua “Jay” Kanassatega, Esq., for his thoughtful discussion and expertise on American Indian law. 1 See Max Millington, The Complete Timeline of Athletes Speaking Out Against Racial Injustice Since the Death of George Floyd, COURIER (Sept. -

SPORTS in LOS ANGELES and ORANGE COUNTIES: an Economic Impact Analysis

SPORTS IN LOS ANGELES AND ORANGE COUNTIES: An Economic Impact Analysis The partnership between the Los Angeles Economic Development Corporation (LAEDC) and the Los Angeles Sports Council (LASC) quantifies the importance of sports to the Greater Los Angeles Region Here in Los Angeles, we know sports are more than just good entertainment — they drive our economic dynamism and expand opportunities for Angelenos and families across our region. Our city is one of the world’s truly great sports towns — and this report reaffirms that what happens in our arenas, ballparks, and fields helps us create jobs, attract investment, and stimulate economic growth. MAYOR ERIC GARCETTI The Regional Impact of Sports 39,000 $6.2 JOBS BILLION in Economic Output $3.3 BILLION $280 in Labor Income MILLION in revenue received The economic $770 by University impact of sports has MILLION Athletic programs INCREASED spent on sporting events annually 11.3 $2.1 BILLION MILLION in the greater MILLIONS attendees at Los Angeles area in donations to professional since 2012 local charities sporting events Major local events such as the Long Beach Grand Prix, L.A. Marathon and Genesis Open % Average Attendance per Home Game 4.7 (IN THOUSANDS) % Other Taxes Los Angeles Clippers 16.58 5.6 and Fees Anaheim Ducks 16.64 Corporate Los Angeles Kings 18.24 Profits Taxes Los Angeles Lakers 18.93 % Los Angeles Football Club 22.04 7.4 Los Angeles Galaxy 24.44 Property Los Angeles Chargers 25.34 Tax Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim 37.29 Los Angeles Dodgers 47.63 36.6% Los Angeles Rams 72.43 % 0 20 40 60 80 10.2 Personal Sales and Income Taxes Excise Taxes Top 5 Universities by Sports Revenue (IN MILLIONS) 140 131 % 35.5 120 117 Social Insurance 100 80 60 State and Local Taxes 40 25 23 21 paid by All Sports 20 0 Organizations UCLA USC Loyola Pepperdine CSU Long Marymount Beach Los Angeles has Los Angeles hosts major professional sports major league championship titles, professional more than any other region west of the Mississippi River. -

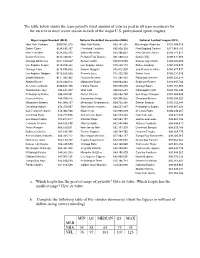

The Table Below Shows the Team Payrolls (Total Amount of Salaries Paid to All Team Members) for the Current Or Most Recent Season in Each of the Major U.S

The table below shows the team payrolls (total amount of salaries paid to all team members) for the current or most recent season in each of the major U.S. professional sports leagues: Major League Baseball (MLB) National Basketball Association (NBA) National Football League (NFL) New York Yankees $209,081,579 New York Knicks $93,341,391 Washington Redskins $123,408,019 Detroit Tigers $138,685,197 Cleveland Cavaliers $85,428,923 New England Patriots $117,963,182 New York Mets $138,293,378 Dallas Mavericks $84,206,021 New Orleans Saints $110,417,011 Boston Red Sox $133,440,037 Portland Trail Blazers $81,508,534 Buffalo Bills $108,875,882 Chicago White Sox $121,152,667 Boston Celtics $78,019,509 Kansas City Chiefs $108,482,459 Los Angeles Angels $119,216,333 Los Angeles Lakers $75,330,112 Dallas Cowboys $107,376,072 Chicago Cubs $118,595,833 Denver Nuggets $73,412,428 San Francisco 49ers $106,877,077 Los Angeles Dodgers $118,536,038 Phoenix Suns $73,222,550 Detroit Lions $106,731,910 Seattle Mariners $117,993,982 Houston Rockets $71,286,452 Pittsburgh Steelers $106,293,914 Atlanta Braves $102,424,018 Milwaukee Bucks $69,084,243 Baltimore Ravens $104,997,764 St. Louis Cardinals $100,624,450 Indiana Pacers $68,898,240 Chicago Bears $104,151,969 Toronto Blue Jays $98,641,957 Utah Jazz $65,632,827 Indianapolis Colts $102,786,398 Philadelphia Phillies $98,269,881 Detroit Pistons $65,503,760 San Diego Chargers $102,460,685 Houston Astros $88,930,415 Sacramento Kings $64,996,855 Cleveland Browns $102,394,922 Milwaukee Brewers $81,004,167 Minnesota Timberwolves $64,728,383 Denver Broncos $102,152,344 Cleveland Indians $78,970,067 New Orleans Hornets $64,547,807 Philadelphia Eagles $100,807,309 San Francisco Giants $76,904,500 Miami Heat $63,888,839 St. -

2017-18 Greensboro Swarm Media Guide

2017-2018 Media Guide 1 /Greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm gsoswarm.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Contact Information 4 2017-2018 Greensboro Swarm Schedule 5 Front Office 6 Basketball Operations 10 2017-18 Greensboro Swarm Roster 11 Player Biographies 25 The NBA G League 28 NBA G League Team Directory 33 Media Information - Greensboro Swarm 34 The Fieldhouse at the Greensboro Coliseum Complex 35 Greensboro Swarm History 37 The Swarm on Social 2 /Greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm gsoswarm.com CONTACT INFORMATION Business Offices The Fieldhouse at the Greensboro Coliseum Complex Address: 2411 West Gate City Blvd. Address: 1921 West Gate City Blvd. Greensboro, NC 27403 Greensboro NC, 27403 Phone: 336-907-3600 3 /Greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm gsoswarm.com SCHEDULE HOME AWAY NBA G League 4 /Greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm @greensboroswarm gsoswarm.com GREENSBORO SWARM STAFF Steve Swetoha – President Prior to his arrival in Greensboro, Swetoha was the President, General Manager and Chief Revenue Officer of the WNBA’s Tulsa Shock for six years. He oversaw both basketball and business operations and lead the team to their first ever playoff appearance in 2015. Swetoha has previous experience in the NFL, NBA, NHL, WNBA and the ACC in various roles ranging from Director of Sales to Senior Vice President of Sales and Retention to Vice President of Business Operations. An alum of Robert Morris University, he earned his Bachelor of Science degree with a concentration in Sport Management and in 2010 was elected to the Robert Morris Sport Management Hall of Fame Class. Swetoha has also earned his Master’s Degree in Sports Leadership at Duquesne University.