Art Casualty of Built History – Curator Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRG 18 Preliminary Inventory ______

_____________________________________________________________________ WOODS BAGOT ARCHITECTS PTY. LTD BRG 18 Preliminary Inventory __________________________________________________________________ Edward Woods (1837-1913) arrived in South Australia during 1860 and began working for the architect Edmund Wright. He helped design the GPO and Town Hall before starting out on his own in 1869; his first commission being St. Peter's Cathedral. By 1884, he had been appointed the colony's Architect-in-chief, and was an inaugural member of the S.A. Institute of Architects formed in 1886. Walter Bagot (1880-1963), a grandson of Henry Ayers and a student of St. Peter's College, became articled to Woods in 1899. He later studied architecture in London before entering into partnership with Woods in 1905. The following year, Bagot assisted with the formation of the first school of architecture in Adelaide, under the auspices of the School of Mines. Herbert Jory, James Irwin and Louis Laybourne-Smith joined the practice as partners in ensuing years; Laybourne-Smith (1880-1965) was also Head of the School of Architecture for 40 years and instrumental in its foundation. Woods Bagot have been a very influential in South Australia, with early emphasis on traditional styles and in ecclesiastical architecture. The firm designed Elder House, the Trustee Building, Bonython Hall, Barr Smith Library, the War Memorial, Carrick Hill and a number of churches in Adelaide and the country. Later commissions included John Martins, the Bank of NSW, CML and Da Costa Buildings, ANZ Bank and the Elizabeth City Centre, while more recent examples include Standard Chartered, Commonwealth Bank, Telecom and Mutual Health buildings. -

A Symposium Exploring Digital Architectural and Built Environment Records

Born digital: a symposium exploring digital architectural and built environment records WORKSHOP PRESENTERS AND PRESENTATION SUMMARIES Monday 18 April 2016 Morning Session 9am-12.30pm Venue: Council Room, Hawke Building Level 5 Welcome and Introduction Assoc Prof Christine Garnaut, Director: Architecture Museum, School of Art Architecture and Design, University of South Australia E: [email protected] Archaeology of the Digital and born-digital archives at CCA Tim Walsh, Digital Archivist, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal The last few decades have seen radical changes in the tools, education, and practice of architecture and design. Archaeology of the Digital is part of a multi-year research project launched by the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) to investigate the development and use of computers in architecture, and the first step in the CCA’s strategic objective of creating a collection of digital architecture. The project, spanning a period of three years and including exhibitions, seminars, public programs and publications, has fostered research around two crucial under-addressed topics: how to collect, preserve, and catalogue born-digital architectural archives, and how to make this material accessible to the public and to researchers. Tim Walsh will share details and experiences from the project, and speak to the opportunities and challenges of archiving born-digital files of architecture and design. Tim Walsh is the Digital Archivist at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, an international research centre and museum in Montreal dedicated to the study of architecture as a public concern. He holds an MS in Library and Information Science from Simmons College, where he concluded his studies with a research paper entitled “Preservation and Access of Born-Digital Architectural Design Records in an OAIS-Type Archive,” and a BA in English from the University of Florida. -

Exhibition Report Thank You

19 FEBRUARY – 22 MAY 2016 EXHIBITION REPORT THANK YOU Museum of Brisbane acknowledges the support of Museum of Brisbane Board many organisations and individuals who helped bring to life Living in the city: New architecture in Brisbane Sallyanne Atkinson ao, Chairman & the Asia-Pacific. The exhibition was spawned by the Andrew Harper inaugural Asia Pacific Architecture Forum, a joint initiative Jeff Humphreys ofArchitecture Media and State Library of Queensland. Alison Kubler The Museum is grateful to these organisations and Chris Tyquin particularly wishes to recognise the invaluable guidance David Askern (Company Secretary) of Architecture Media’s Cameron Bruhn. The Museum also acknowledges the support of Audi Centre Brisbane as Museum Partner, Hilton Hotel Brisbane as Accommodation Partner, and Media Partner’s goa, 612 ABC Brisbane and The Weekend Edition. It is only with the support of these organisations that the Museum can deliver award-winning exhibitions free for the community. Museum Partner Accommodation Partner Media Partners Exhibition Supporters Living in the city is co-presented with Architecture Media Life at Home: Richard Kirk Architect, Courtyard Residence 2015, as part of Asia Pacific Architecture Forum. architectural illustration Cover: Making Communities: HASSELL, Shenzhen Affordable Housing Design 2012, architectural rendering FAST FACTS 75,334 people visited Museum of Brisbane during the exhibition Making Communities: The University of Queensland Student Housing 6 public programs Precinct, St Lucia, Wilson Architects -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Deakin Research Online

Deakin Research Online This is the published version: Jones, David 2011, Bagot, Walter, in The encyclopedia of Australian architecture, Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, Vic., pp.60-60. Available from Deakin Research Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30041726 Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright owner. Copyright: 2011, Cambridge University Press in Domestic Architecture in Australia (1919), Some nineteenth BAGOT, WALTER century Adelaide architects (1958), 'Early Adelaide architecture' WALTER Hervey Bagot (1880- 1963) was born in North (1953-8), edited Reveries in retrospect (1946), written by his Adelaide, son of a prominent stockbroker and pastoralist. He wife,]osephine Margaret Barritt, and regularly lectured on was apprenticed in 1899 to Edward Woods, later studying Italian painting at the Art Gallery of SA. He was the recipient architecture at King's College, London (1902- 5). Upon his of a Worshipful Company of Carpenters silver medal (1903), return to Adelaide in 1905, Woods offered him a partnership, RIBA associateship (1904) and FRIBA (1926); served as RAIA establishing the practice Woods Bagot (later known variously (SA) President (1917-19), was elevated to LFRAIA (1960); as Woods Bagot Laybourne-Smith & Irwin). Described as a and created a Cavaliere Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana 'master of architectural detail, both classic and medieval', he (Knight of the Order of Merit of the Republic ofItaly) in 1962 was passionate about classical and traditional designs, especially for services to the Australian- Italian Association. northern Italian architecture. He spending many summers DAV ID JONES there, embracing, in his writings and designs, the climatic relevance and appropriateness of this style for Adelaide and its J. -

4.1 Attachment a Forest Lodge Heritage Survey (2008) Recommendation : State Heritage Place

4.1 Attachment A Forest Lodge Heritage Survey (2008) Recommendation : State Heritage Place NAME: Forest Lodge house, outbuildings, garden and garden components PLACE NO.: 16242 Address: 19 Pine Street, Aldgate SUMMARY OF HERITAGE VALUE: Description: 'Forest Lodge' is an extensive Victorian era property comprising a 'hill-station' residence and intricate parterred garden within a pinetum, located between Stirling and Aldgate in the Adelaide Hills. The pinetum is the largest conifer collection in South Australia, and one of the largest and most mature in Australia. The austere Victorian Baronial-style residence was constructed by Walter C Torode to a design by architect Ernest Henry Bayer creating a grand two-storey freestone structure characterised by a three-storey castellated tower, terra cotta chimney pots, with associated bathhouse and water tower. Later additions maintained this architectural style. Changes to the landscape design between the 1890s to the 1930s ·introduced a northern Italian design style under architect Walter Bagot but did not compromise the original Victorian character and plantings. These components include: Main Residence: a grand Victorian Baronial style two storey residence constructed by prominent builder Walter Torode to a design by Ernest Bayer, largely constructed while the Bagot's were on their 'grand tour', featuring a castellated lookout tower and aspects to the east and south offering views over the newly established and now mature gardens. Woodland I Arboretum: an extensive open woodland arboretum, -

BARR SMITH LIBRARY University of Adelaide

Heritage of the City of Adelaide BARR SMITH LIBRARY University of Adelaide Off North Terrace This classically derived building is in stark contrast to Walter Hervey Bagot's other university building, the Bonython Hall, which was built in the mediaeval Gothic style. The library, of red-brick, stone dressings and freestone portico, is reminiscent of Georgian England, imposing, but elegant. It has also been likened to similar buildings at Harvard University. The original library complex dominates the main university lawns opposite the Victoria Drive Gates, enhanced by mature trees, and blends with the various other buildings also in red-brick and of this century. The Barr Smith Library is a memorial to Robert Barr Smith who from 1892 bequeathed large sums of money to purchase books for the university library. After his death in 1915 the family made the maintenance of the Library its concern. Following his father, Thomas Elder Barr Smith became a member of the council in 1924 and offered £20 000 for a new library to relieve the congested state of the one in the Mitchell Building. He increased his gift to cover the expected building cost of £34 000. Walter Bagot chose a classic style for the proposed library. The pamphlet describing the official opening of the Barr Smith Library stated that: The tradition that the mediaeval styles are appropriate to educational buildings dies hard; but it is dying. Climate is the dominant factor, and a mediterranean climate such as this should predispose us to a mediterranean, that is to say, a classic form of architecture . -

Woods Bagot: Creating Immense Projects on a Human Scale

MAY 19 MAY ISSUE 35 HAS GREENWASHING STAGNATED SUSTAINABLE DESIGN? WOODS BAGOT: CREATING IMMENSE PROJECTS ON A HUMAN SCALE CAN DESIGN HELP CHANGE A WORKSPACE'S CULTURE? A LOOK AT DENTSU AEGIS NETWORK'S SCHIAVELLO.COM WELLNESS-FOCUSED WORKSPACE PROJECTS PEOPLE DESIGN KNOWLEDGE NEWS CULTURE SCHIAVELLOFURNITURE.COM/AGILE-TABLE Hello. Welcome to Details 35. Since the beginnings of Schiavello over 50 years ago, we have always pushed boundaries, never satisfied with merely meeting the status quo. In property development, construction and furniture, we are constantly asking how we can do more, do better, and excel further than has previously been achieved. This approach is perfectly encapsulated in our company motto, ‘Anything is possible.’ In this issue of the magazine, we explore this practice in a few different ways. On pg. 16, Sara Kirby takes a critical look at greenwashing, how it has stagnated the design industry, and what the future of sustainable design looks like. She explores how we can look past media spin and push to make our future more environmentally sustainable, something that we as a company are deeply invested in. In our profile section (pg. 12), Sandra Tan talks to Grant Boshard of Woods Bagot, a studio that needs no introduction. Together the pair reveals how Woods Bagot has achieved such an enduring legacy – with an answer that is, at least partially, to do with the practice’s open embracing of change and constant questioning of how it can adapt and be better. For Schiavello, we profile Dentsu Aegis Network (DAN) Perth, a project we took on right from the beginning, all the way through to the moment the ribbon was cut on opening day. -

Hybrid Beauty and Vigour All of Its Own and Which Will Blossom Abundantly in the Waste Places of New Guinea’

an architect,Hybrid a missionary, and their Beauty improbable desires Newell Platten Contents Introduction viii Part one ....................................................................... 1 Marnoo to Modernism 3 2 The grand tour 14 3 Settling down 37 4 Dickson and Platten: the early years 51 5 Greece 62 6 Dickson and Platten: the later years 91 7 Town planning, citizens’ campaign – and Monarto 107 8 The South Australian Housing Trust 117 9 Interlude 129 Part two ....................................................................... 1 Ancestors 135 2 The Jewel of the Pacific 143 3 Land of childhood dreaming 169 4 Southern sojourn 197 5 Volcano bride 204 6 Prelude to war 220 7 Rabaul: a town no more 233 8 Last music 253 Part three ..................................................................... Epilogue 270 Acknowledgments, bibliography and photographs 282 Index 287 Map of Bismarck Archipelago Introduction y father’s final moments in a church before a handful of mourners, none of whom had prepared a eulogy, left me with a profound Msense of anti-climax, almost distress that a life that had been lived in exotic places, had been idealistic, adventurous, selfless and in many ways exemplary should pass so unremarked. On retiring from my own professional career I wanted to make good the omission and give voice to his silence, so I have spent many hours tapping out the story of his life. Perhaps not wanting to suffer a similar if more appropriate exit, I wrote my own memoir. Kind people read them, making various suggestions. One friend told me everyone was writing schoolday stories; no one wanted to read about missionaries nowadays, but perhaps, a document on my years as an architect, and his in the mission field, might work if I identified the necessary unifying themes. -

GARDENS in SOUTH AUSTRALIA 1840 - 1940 Guidelines for Design 2 5 and Conservation

HERITAGE CONSERVATION GARDENS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 1840 - 1940 Guidelines for Design 2 5 and Conservation D NR DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES The financial assistance made by the following to this publication is gratefully acknowledged: Park Lane Garden Furniture South Australian Distributor of Lister Solid Teak English Garden Furniture and Lloyd Loom Woven Fibre Furniture Phone (08) 8295 6766 Garden Feature Plants Low maintenance garden designs and English formal and informal gardens Phone (08) 8271 1185 Published By DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES City of Adelaide May 1998 Heritage South Australia © Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs & the Corporation of the City of Adelaide ISSN 1035-5138 Prepared by Heritage South Australia Text, Figures & Photographs by Dr David Jones & Dr Pauline Payne, The University of Adelaide Contributions by Trevor Nottle, and Original Illustrations by Isobel Paton Design and illustrations by Eija Murch-Lempinen, MODERN PLANET design Acknowledgements: Tony Whitehill, Thekla Reichstein, Christine Garnaut, Alison Radford, Elsie Maine Nicholas, Ray Sweeting, Karen Saxby, Dr Brian Morley, Maggie Ragless, Barry Rowney, Mitcham Heritage Resources Centre, Botanic Gardens of Adelaide, Mortlock Library of the State Library of South Australia, The Waikerie & District Historical Society, Stephen & Necia Gilbert, and the City of West Torrens. Note: Examples of public and private gardens are used in this publication. Please respect the privacy of owners. Cover: Members -

Register of Architects & Non Practising Architects

REGISTER OF ARCHITECTS & NON PRACTISING ARCHITECTS Copyright The Board of Architects of Queensland supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this document. The Board of Architects of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically , provided it is for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation; this material remains unaltered and the Board of Architects of Queensland is recognised as the owner. Enquiries should be addressed to: [email protected] Register As At 29 June 2021 In pursuance of the provision of section 102 of Architects Act 2002 the following copy of the Register of Architects and Non Practicing Architects is published for general information. Reg. No. Name Address Bus. Tel. No. Architects 5513 ABAS, Lawrence James Ahmad Gresley Abas 03 9017 4602 292 Victoria Street BRUNSWICK VIC 3056 Australia 4302 ABBETT, Kate Emmaline Wallacebrice Architecture Studio (07) 3129 5719 Suite 1, Level 5 80 Petrie Terrace Brisbane QLD 4000 Australia 5531 ABBOUD, Rana Rita BVN Architecture Pty Ltd 07 3852 2525 L4/ 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Australia 4524 ABEL, Patricia Grace Elevation Architecture 07 3251 6900 5/3 Montpelier Road NEWSTEAD QLD 4006 Australia 0923 ABERNETHY, Raymond Eric Abernethy & Associates Architects 0409411940 7 Valentine Street TOOWONG QLD 4066 Australia 5224 ABOU MOGHDEB EL DEBES, GHDWoodhead 0403 400 954 Nibraz Jadaan Level 9, 145 Ann Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Australia 4945 ABRAHAM, -

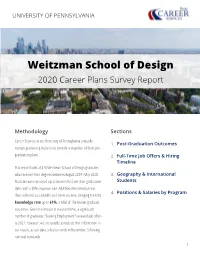

Weitzman School of Design

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Weitzman School of Design 2020 Career Plans Survey Report Methodology Sections Career Services at the University of Pennsylvania annually 1. Post-Graduation Outcomes surveys graduating students to provide a snapshot of their post- graduation plans. 2. Full-Time Job Offers & Hiring Timeline This report looks at 320 Weitzman School of Design graduates who received their degrees between August 2019–May 2020. 3. Geography & International Students were surveyed up to six months from their graduation Students date, with a 39% response rate. Additional information was 4. Positions & Salaries by Program then collected via LinkedIn and other sources, bringing the total knowledge rate up to 61%, a total of 196 known graduate outcomes. Given the impact of the pandemic, a significant number of graduates “Seeking Employment” received job offers in 2021. However, we are unable to include that information in our report, as our data collection ends in November, following national standards. 1 2020 WEITZMAN SCHOOL OF DESIGN CAREER PLAN REPORT Post-Graduation by the Numbers 196 responses Full-Time Employment 74.0% Seeking Employment 20.9% Given the impact of the pandemic, a significant Part-Time Employment 2.0% number of graduates “Seeking Employment” received Continuing Education 2.0% job offers in 2021. However, we are unable to include that information in our report, as our data collection Seeking Continuing Education 0.5% ends in November, following national standards. Not Seeking 0.5% 78.1% of graduates were either employed or enrolled in continuing education within the first 6 months after graduation. Outcomes by Program 196 responses - graduates from multiple programs are counted once in each program.