Cultural Resources Overview Little Colorado Area, Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona & New Mexico

THE MOST DEPEN DABLE way to and from The partnership between Southeastern Freight Lines and Central Arizona Freight offers you the unique combination of the premium LTL service providers in the ARIZONA & Southwest States of Arizona and New Mexico and the Southeast and Southwest. NEW MEXICO Why Central Arizona Freight? “Simply offer the best when it comes to Quality Service” • Privately Owned • Union-Free • Full data connectivity to provide complete shipment visibility • Premiere LTL carrier in Arizona and New Mexico • 60% of shipments deliver before noon t Times Transi Sample 1 hoenix aso to P El P que 3 buquer is to Al Memph 3 gman s to Kin Dalla 4 uerque Albuq iami to 4 M Tucson rlotte to Cha 4 well to Ros Atlanta Customer Testimonial: “Harmar uses Southeastern Freight Lines through your direct service and your partnership service. We ship throughout the United States, and Puerto Rico. A lot of our business moves into the Southwest, which is serviced by your partner Central Ari - zona Freight. Before we gave this business to you guys, we were using another carrier for these moves. We were experiencing service issues. We decided to make a switch to your company and their partner. Since we made the change, the service issues have diminished greatly, if not gone away. Being able to get our customers their shipments on time and damage-free was worth the change. Thank you so much, Southeastern Freight Lines and Central Arizona Freight, for making our shipping operation seamless and non-event.” Kevin Kaminski, Director - Supply Chain & Strategic Sourcing Harmar CONTACT YOUR LOCAL SOUTHEASTERN www.sefl.com FREIGHT LINES OFFICE FOR RATES 1.800.637.7335. -

The Deveiopment and Functions of the Army In

The development and functions of the army in new Spain, 1760-1798 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Peloso, Vincent C. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 10:56:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319751 THE DEVEIOPMENT AND FUNCTIONS OF THE ARMY IN NEW SPAIN, 1760-1798 Vincent Peloso A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 5 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduc tion of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of schol arship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

(NTUA) – Navajo Townsite NPDES Permit No

December 2011 FACT SHEET Authorization to Discharge under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System for the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA) – Navajo Townsite NPDES Permit No. NN0030335 Applicant address: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (“NTUA”) P.O. Box 587 Fort Defiance, Arizona 86504 Applicant Contact: Harry L. Begaye, Technical Assistant (928) 729-6208 Facility Address: 0.5 miles west of Navajo Pine High School West of Black Creek Wash in Navajo, NM Facility Contact: Philemon Allison, District Manager (928) 729-6140 I. Summary The NTUA was issued a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) Permit (No. NN0030335) on December 23, 2006, for its Navajo Townsite wastewater treatment lagoon facility (“WWTF”), pursuant to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“U.S. EPA”) regulations set forth in Title 40, Code of Federal Regulations (“CFR”) Part 122.21. The permit was effective December 23, 2006, through midnight, December 22, 2011. NTUA applied to U.S. EPA Region 9 for reissuance on August 16, 2011. This fact sheet is based on information provided by the applicant through its application and discharge data submittal, along with the appropriate laws and regulations. Pursuant to Section 402 of the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), the U.S. EPA is proposing issuance of the NPDES permit renewal to NTUA Navajo Townsite (“permittee”) for the discharge of treated domestic wastewater to receiving waters named Black Creek, a tributary to Puerco River, an eventual tributary to the Little Colorado River, a water of the United States. II. Description of Facility The NTUA Navajo Townsite wastewater treatment lagoons are located 0.5 miles west of Navajo Pine High School, west of Black Creek Wash in Navajo New Mexico. -

Arroyo 2015 States and Mexico Through a Treaty, Apportioned 1.5 MAF Elevation 1075 Feet

2015 Closing the Water Demand-Supply Gap in Arizona There is an acknowledged gap between future water of water. As a result, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to demand and supply available in Arizona. In some parts of closing the water demand-supply gap. Arizona, the gap exists today, where water users have been living on groundwater for a while, often depleting what Introduction can be thought of as their water savings account. In other places, active water storage programs are adding to water Many information sources were used to develop this savings accounts. The picture is complicated by variability issue of the Arroyo, which summarizes Arizona’s current in the major factors affecting sources and uses of water water situation, future challenges, and options for closing resources. Water supply depends on the volume that nature the looming water demand-supply gap. Three major provides, the location and condition of these sources, and documents, however, provide its foundation. All three the amount of reservoir storage available. Demand for water conclude that there is likely to be a widening gap between reflects population growth, the type of use, efficiency of supply and demand by mid-century unless mitigating use, and the location of that use. In a relatively short time actions are taken. frame, from 1980 to 2009, Arizona’s population grew from The first document is the Colorado River Basin Water 2.7 million people with a $30-billion economy to nearly 6.6 Supply and Demand Study (http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/ million people with a $260-billion economy. -

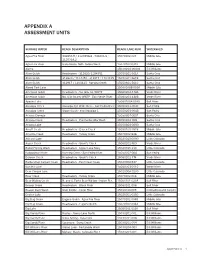

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Permian Stratigraphy of the Defiance Plateau, Arizona H

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/18 Permian stratigraphy of the Defiance Plateau, Arizona H. Wesley Peirce, 1967, pp. 57-62 in: Defiance, Zuni, Mt. Taylor Region (Arizona and New Mexico), Trauger, F. D.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 18th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 228 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1967 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Rainfall-Runoff Model for Black Creek Watershed, Navajo Nation

Rainfall-Runoff Model for Black Creek Watershed, Navajo Nation Item Type text; Proceedings Authors Tecle, Aregai; Heinrich, Paul; Leeper, John; Tallsalt-Robertson, Jolene Publisher Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Journal Hydrology and Water Resources in Arizona and the Southwest Rights Copyright ©, where appropriate, is held by the author. Download date 25/09/2021 20:12:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/301297 37 RAINFALL-RUNOFF MODEL FOR BLACK CREEK WATERSHED, NAVAJO NATION Aregai Tecle1, Paul Heinrich1, John Leeper2, and Jolene Tallsalt-Robertson2 ABSTRACT This paper develops a rainfall-runoff model for estimating surface and peak flow rates from precipitation storm events on the Black Creek watershed in the Navajo Nation. The Black Creek watershed lies in the southern part of the Navajo Nation between the Defiance Plateau on the west and the Chuska Mountains on the east. The area is in the semiarid part of the Colorado Plateau on which there is about 10 inches of precipitation a year. We have two main purposes for embarking on the study. One is to determine the amount of runoff and peak flow rate generated from rainfall storm events falling on the 655 square mile watershed and the second is to provide the Navajo Nation with a method for estimating water yield and peak flow in the absence of adequate data. Two models, Watershed Modeling System (WMS) and the Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC) Hydrological Modeling System (HMS) that have Geographic Information System (GIS) capabilities are used to generate stream hydrographs. Figure 1. Physiographic map of the Navajo Nation with the Chuska The latter show peak flow rates and total amounts of Mountain and Deance Plateau and Stream Gaging Stations. -

List of Surrounding States *For Those Chapters That Are Made up of More Than One State We Will Submit Education to the States and Surround States of the Chapter

List of Surrounding States *For those Chapters that are made up of more than one state we will submit education to the states and surround states of the Chapter. Hawaii accepts credit for education if approved in state in which class is being held Accepts credit for education if approved in state in which class is being held Virginia will accept Continuing Education hours without prior approval. All Qualifying Education must be approved by them. Offering In Will submit to Alaska Alabama Florida Georgia Mississippi South Carolina Texas Arkansas Kansas Louisiana Missouri Mississippi Oklahoma Tennessee Texas Arizona California Colorado New Mexico Nevada Utah California Arizona Nevada Oregon Colorado Arizona Kansas Nebraska New Mexico Oklahoma Texas Utah Wyoming Connecticut Massachusetts New Jersey New York Rhode Island District of Columbia Delaware Maryland Pennsylvania Virginia West Virginia Delaware District of Columbia Maryland New Jersey Pennsylvania Florida Alabama Georgia Georgia Alabama Florida North Carolina South Carolina Tennessee Hawaii Iowa Illinois Missouri Minnesota Nebraska South Dakota Wisconsin Idaho Montana Nevada Oregon Utah Washington Wyoming Illinois Illinois Indiana Kentucky Michigan Missouri Tennessee Wisconsin Indiana Illinois Kentucky Michigan Ohio Wisconsin Kansas Colorado Missouri Nebraska Oklahoma Kentucky Illinois Indiana Missouri Ohio Tennessee Virginia West Virginia Louisiana Arkansas Mississippi Texas Massachusetts Connecticut Maine New Hampshire New York Rhode Island Vermont Maryland Delaware District of Columbia -

Grand Circle

Salt Lake City Green River - Moab Salt Lake City - Green River 60min (56mile) Grand Junction 180min (183mile) Colorado Crescent Jct. NM Great Basin Green River NP Arches NP Moab - Arches Goblin Valley 10min (5mile) SP Corona Arch Moab Grand Circle Map Capitol Reef - Green River Dead Horse Point 100min (90mile) SP Moab - Grand View Point NP: National Park 80min (45mile) NM: National Monument NHP: National Histrocal Park Bryce Canyon - Capitol Reef Canyonlands SP: State Park Capitol Reef COLORADO 170min (123mile) NP NP Moab - Mesa Verde Monticello Moab - Monument Valley 170min (140mile) NEVADA UTAH 170min (149mile) Bryce Cedar City Canyon NP Natural Bridges Canyon of the Cedar Breaks NM Blanding Ancients NM Mesa Verde - Monument Valley NM Kodacrome Basin SP 200min (150mile) Valley of Hovenweep 40min 70min NM Cortez (24mile) (60mile) Grand Staircase- the Gods 100min Escalante NM Durango Mt. Carmel (92mile) Muley Point Snow Canyon Jct. SP Goosenecks SP Zion NP Kanab Lake Powell Mexican Hat Mesa Verde Rainbow Monument Valley NP Coral Pink Sand Vermillion Page Bridge NM Four Corners Las Vegas - Zion Dunes SP Cliffs NM Navajo Tribal Park Aztec Ruins NM 170min (167mile) Antelope Pipe Spring NM Horseshoe Shiprock Aztec Bend Canyon Mesa Verde - Chinle 200min (166mile) Mt.Carmel Jct. - North Rim Navajo NM 140min (98mile) Kayenta Farmington Monument Valley - Chinle Mesa Verde - Chaco Culture Valley of Fire Page - North Rim Page - Cameron Page - Monument Valley 140min (134mile) 230min (160mile) SP 170min (124mile) 90min (83mile) Grand Canyon- 130min -

THE WATER QUALITY of the LITTLE COLORADO RIVER WATERSHED Fiscal Year 2007

THE WATER QUALITY OF THE LITTLE COLORADO RIVER WATERSHED Fiscal Year 2007 Prepared by the Surface Water Section March 2009 Publication Number OFR 09-11 LCR REPORT FY 2007 THE WATER QUALITY OF THE LITTLE COLORADO RIVER WATERSHED Fiscal Year 2007 By The Monitoring and Assessments Units Edited by Jason Jones and Meghan Smart Arizona Department of Environmental Quality ADEQ Water Quality Division Surface Water Section Monitoring Unit, Standards & Assessment Unit 1110 West Washington St. Phoenix, Arizona 85007-2935 ii LCR REPORT FY 2007 THANKS: Field Assistance: Anel Avila, Justin Bern, Aiko Condon, Kurt Ehrenburg, Karyn Hanson, Lee Johnson, Jason Jones, Lin Lawson, Sam Rector, Patti Spindler, Meghan Smart, and John Woods. Report Review: Kurt Ehrenburg, Lin Lawson, and Patti Spindler. Report Cover: From left to right: EMAP team including ADEQ, AZGF, and USGS; Rainbow over the Round Valley in the White Mountains; Measuring Tape, and Clear Creek located east of Payson. iii LCR REPORT FY 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Abbreviation Name Abbreviation Name ALKCACO3 Total Alkalinity SO4-T Sulfate Total ALKPHEN Phenolphthalein Alkalinity SPCOND Specific Conductivity Arizona Department of Suspended Sediment AQEQ Environmental Quality SSC Concentration AS-D Arsenic Dissolved su Standard pH Units AS-T Arsenic Total TDS Total Dissolved Solids Arizona Game and Fish AZGF Department TEMP-AIR Air Temperature Arizona Pollutant Discharge TEMP- AZPDES Elimination System WATER Water Temperature BA-D Barium Dissolved TKN Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen B-T Boron Total TMDL Total Maximum Daily Load CA-T Calcium Total USGS U.S. Geological Survey CFS Cubic Feet per Second ZN-D Zinc Dissolved CO3 Carbonate ZN-T Zinc Total CU-TRACE Copper Trace Metal CWA Clean Water Act DO-MGL Dissolved Oxygen in mg/l DO- PERCENT Dissolved Oxygen in Percent E. -

Oak Creek Canyon

' " United States (. Il). Department of \~~!J'~~':P Agriculture CoconinoNational Forest Service ForestPlan Southwestern Region -""""" IU!S. IIIII.IIIIII... I I i I--- I I II I /"r, Vicinity Map @ , " .. .' , ",', '. ',,' , ". ,.' , ' ' .. .' ':':: ~'::.»>::~: '::. Published August 1987 Coconino N.ational Forest Land and Resource Management Plan This Page Intentionally Left Blank Coconino Foresst Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION Purpose of the Plan. 1 Organization of the Forest Plan Documentation. 2 Planning Area Description. 2 2. ISSUES Overview . 5 Issues . 5 Firewood . 6 Timber Harvest Levels. 7 The Availability of Recreation Options . 8 Off-Road Driving . 9 Wildlife Habitat . 9 Riparian Habitat . 11 Geothermal Development . .. 11 Management of the Transportation System . 12 Use of the Public Lands . 13 Law Enforcement . 13 Landownership Adjustment . 14 Opportunities . 14 Public Affairs . 14 Volunteers . 15 3. SUMMARY OF THE ANALYSIS OF THE MANAGEMENT SITUATION Overview . 17 Prior Allocations . 18 4. MANAGEMENT DIRECTION Overview . 21 Mission . 21 Goals . 21 Objectives . 26 Regional Guide/Forest Plan . 26 Outputs & Range of Implementation . 26 Management Prescriptions . 46 Management Area Description . 46 Management Emphasis . 46 Program Components . 46 Activities . .. 47 Standards and Guidelines . 47 How to Apply Prescriptions . .. 47 Coordinating Requirements . .. 47 Coconino National Forest Plan – Partial Cancellation of Amendment No. 15 -3/05 Replacement Page i Coconino Forest Plan Table of Contents continued Standards and Guidelines . 51 Forest-wide . 51 MA 1 Wildernesses . 98 MA 2 Verde Wild and Scenic River . .. 113 MA 3 Ponderosa Pine and Mixed Conifer, Less Than 40 Percent Slopes. .. 116 MA 4 Ponderosa Pine and Mixed Conifer, Greater Than 40 Percent Slopes. 138 MA 5 Aspen . 141 MA 6 Unproductive Timber Land . -

EMERGING CONTAMINANTS in ARIZONA WATER a Status Report September 2016

EMERGING CONTAMINANTS IN ARIZONA WATER A Status Report September 2016 CONTAMINANT ASSESSMENT • MONITORING • RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES • IMPACTS • RESOURCES • COMMUNICATION & OUTREACH Acknowledgements Misael Cabrera APEC Sponsor, ADEQ Director Henry Darwin APEC Sponsor, ADEQ Director (former) Trevor Baggiore APEC Chair, ADEQ Water Quality Division Director Mike Fulton APEC Chair, ADEQ Water Quality Division Director (former) Randy Gottler APEC Co-Chair, City of Phoenix Committee Chairs/Co-chairs* Dan Quintanar Chair, Outreach and Education Committee Tucson Water John Kmiec Chair, Chemical EC Committee Town of Marana Dr. Jeff Prevatt Chair, Microbial EC Committee Pima County Regional Wastewater Reclamation Dept. Cindy Garcia (M) Co-chair, Outreach and Education Committee City of Peoria Jamie McCullough Co-chair, Outreach and Education Committee City of El Mirage Dr. Channah Rock Co-chair, Outreach and Education Committee University of Arizona, Maricopa Agricultural Center Laura McCasland (O) Co-chair, Chemical EC Committee City of Scottsdale Steve Baker Co-chair, Microbial EC Committee Arizona Dept. of Health Services, Division of Public Health Services Additional APEC Members* Dr. Morteza Abbaszadegan (M) Arizona State University, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Leif Abrell (C,M) University of Arizona, Arizona Laboratory for Emerging Contaminants Jennifer Botsford (C,O) Arizona Dept. of Health Services, Office of Environmental Health Dr. Kelly Bright (M) University of Arizona, Soil, Water & Environmental Science Al Brown (O) Arizona State University, The Polytechnic School Dr. Mark Brusseau (C,O) University of Arizona, School of Earth & Environmental Sciences Alissa Coes (C) U.S. Geological Survey, Arizona Water Science Center Nick Paretti U.S. Geological Survey, Arizona Water Science Center Patrick Cunningham (O) The Law Office of Patrick J.