David Lewis's Philosophy of Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Semantics in Generative Grammar. by Irene Heim & Angelika Kratzer

Semantics in generative grammar. By Irene Heim & Angelika Kratzer. Malden & Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. Pp. ix, 324. Introduction to natural language semantics. By Henriëtte de Swart. Stanford: CSLI Publications, 1998. Pp. xiv, 257. Although there aren’t that many text books on formal semantics, their average quality is quite good, and these two recent additions don’t lower the standard by any means. ‘Semantics in generative grammar’ (SGG) is the more innovative of the two. As its title indicates, SGG focuses its attention on the syntax/semantics interface, with particular emphasis on quantification and anaphora. These two subjects are discussed in considerable detail, while many others receive only a cursory treatment or are not addressed at all. We learn from the preface that this was a deliberate choice: ‘We want to help students develop the ability for semantic analysis, and, in view of this goal, we think that exploring a few topics in detail is more effective than offering a bird’s-eye view of everything.’ (p. ix) Having enjoyed the results of Heim and Kratzer’s explorations, I can only agree with this judgment. SGG falls into three main parts. The first part introduces the two notions that are at the heart of the formal semantics enterprise, viz. truth conditions and compositionality, and then goes on to develop a compositional truth- conditional semantics for a core fragment of English. The second part discusses variable binding and quantification, and the third part is an in-depth discussion of anaphora. All these developments are kept within an extensional framework. 06-09-1999 1 Intensional phenomena are addressed only briefly, in the last chapter of the book. -

Sentence Types and Functions

San José State University Writing Center www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter Written by Sarah Andersen Sentence Types and Functions Choosing what types of sentences to use in an essay can be challenging for several reasons. The writer must consider the following questions: Are my ideas simple or complex? Do my ideas require shorter statements or longer explanations? How do I express my ideas clearly? This handout discusses the basic components of a sentence, the different types of sentences, and various functions of each type of sentence. What Is a Sentence? A sentence is a complete set of words that conveys meaning. A sentence can communicate o a statement (I am studying.) o a command (Go away.) o an exclamation (I’m so excited!) o a question (What time is it?) A sentence is composed of one or more clauses. A clause contains a subject and verb. Independent and Dependent Clauses There are two types of clauses: independent clauses and dependent clauses. A sentence contains at least one independent clause and may contain one or more dependent clauses. An independent clause (or main clause) o is a complete thought. o can stand by itself. A dependent clause (or subordinate clause) o is an incomplete thought. o cannot stand by itself. You can spot a dependent clause by identifying the subordinating conjunction. A subordinating conjunction creates a dependent clause that relies on the rest of the sentence for meaning. The following list provides some examples of subordinating conjunctions. after although as because before even though if since though when while until unless whereas Independent and Dependent Clauses Independent clause: When I go to the movies, I usually buy popcorn. -

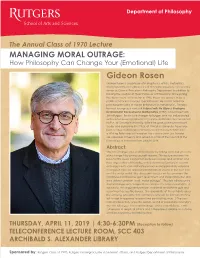

Gideon Rosen Gideon Rosen Is a Professor of Metaphysics, Ethics, Metaethics, and Philosophy of Mathematics at Princeton University

Department of Philosophy The Annual Class of 1970 Lecture MANAGING MORAL OUTRAGE: How Philosophy Can Change Your (Emotional) Life Gideon Rosen Gideon Rosen is a professor of metaphysics, ethics, metaethics, and philosophy of mathematics at Princeton University. He currently serves as Chair of Princeton’s Philosophy Department in addition to holding the position of Stuart Professor of Philosophy. Since joining the department at Princeton in 1993, Rosen has proved to be a prolific scholar in his various specializations. He is most noted for proposing the idea of modal fictionalism in metaphysics. Perhaps his most recognized work is A Subject with No Object: Strategies for Nominalist Reconstrual in Mathematics (1997), coauthored with John Burgess. Rosen is no stranger to Rutgers and has collaborated with various Rutgers professors on papers and books. He completed his B.A. at Columbia University, where he graduated summa cum laude, and completed his Ph.D. at Princeton University. Rosen has held a Hauser Fellowship in Global Law at NYU Law School and a Whiting Fellowship at Princeton. He is also a John Jay Scholar via Columbia University and served as Chair of the Council of the Humanities at Princeton from 2006 to 2014. Abstract: You can change your emotional state by taking a pill, but you can also change it by giving yourself reasons. This lecture explores the basis for this deep connection between reason and emotion and then argues that philosophy, with its distinctive battery of reasons and arguments, can motivate pervasive and potentially valuable changes in how we respond emotionally to events in our own lives and the wider world. -

Mark Schroeder [email protected] 3709 Trousdale Parkway Markschroeder.Net

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ USC School of Philosophy 323.632.8757 (mobile) Mudd Hall of Philosophy Mark Schroeder [email protected] 3709 Trousdale Parkway markschroeder.net Los Angeles, CA 90089-0451 Curriculum Vitae philosophy.academy ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Ph.D., Philosophy, Princeton University, November 2004, supervised by Gideon Rosen M.A., Philosophy, Princeton University, November 2002 B.A., magna cum laude, Philosophy, Mathematics, and Economics, Carleton College, June 2000 EMPLOYMENT University of Southern California, Professor since December 2011 previously Assistant Professor 8/06 – 4/08, Associate Professor with tenure 4/08 – 12/11 University of Maryland at College Park, Instructor 8/04 – 1/05, Assistant Professor 1/05 – 6/06 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ RESEARCH INTERESTS My research has focused primarily on metaethics, practical reason, and related areas, particularly including normative ethics, philosophy of language, epistemology, philosophy of mind, metaphysics, the philosophy of action, agency, and responsibility, and the history of ethics. HONORS AND AWARDS Elected to USC chapter of Phi Kappa Phi, 2020; 2017 Phi Kappa Phi Faculty -

The Meaning of Language

01:615:201 Introduction to Linguistic Theory Adam Szczegielniak The Meaning of Language Copyright in part: Cengage learning The Meaning of Language • When you know a language you know: • When a word is meaningful or meaningless, when a word has two meanings, when two words have the same meaning, and what words refer to (in the real world or imagination) • When a sentence is meaningful or meaningless, when a sentence has two meanings, when two sentences have the same meaning, and whether a sentence is true or false (the truth conditions of the sentence) • Semantics is the study of the meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences – Lexical semantics: the meaning of words and the relationships among words – Phrasal or sentential semantics: the meaning of syntactic units larger than one word Truth • Compositional semantics: formulating semantic rules that build the meaning of a sentence based on the meaning of the words and how they combine – Also known as truth-conditional semantics because the speaker’ s knowledge of truth conditions is central Truth • If you know the meaning of a sentence, you can determine under what conditions it is true or false – You don’ t need to know whether or not a sentence is true or false to understand it, so knowing the meaning of a sentence means knowing under what circumstances it would be true or false • Most sentences are true or false depending on the situation – But some sentences are always true (tautologies) – And some are always false (contradictions) Entailment and Related Notions • Entailment: one sentence entails another if whenever the first sentence is true the second one must be true also Jack swims beautifully. -

David Lewis on Convention

David Lewis on Convention Ernie Lepore and Matthew Stone Center for Cognitive Science Rutgers University David Lewis’s landmark Convention starts its exploration of the notion of a convention with a brilliant insight: we need a distinctive social competence to solve coordination problems. Convention, for Lewis, is the canonical form that this social competence takes when it is grounded in agents’ knowledge and experience of one another’s self-consciously flexible behavior. Lewis meant for his theory to describe a wide range of cultural devices we use to act together effectively; but he was particularly concerned in applying this notion to make sense of our knowledge of meaning. In this chapter, we give an overview of Lewis’s theory of convention, and explore its implications for linguistic theory, and especially for problems at the interface of the semantics and pragmatics of natural language. In §1, we discuss Lewis’s understanding of coordination problems, emphasizing how coordination allows for a uniform characterization of practical activity and of signaling in communication. In §2, we introduce Lewis’s account of convention and show how he uses it to make sense of the idea that a linguistic expression can come to be associated with its meaning by a convention. Lewis’s account has come in for a lot of criticism, and we close in §3 by addressing some of the key difficulties in thinking of meaning as conventional in Lewis’s sense. The critical literature on Lewis’s account of convention is much wider than we can fully survey in this chapter, and so we recommend for a discussion of convention as a more general phenomenon Rescorla (2011). -

Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals As Windows Into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer

University of Massachusetts Amherst From the SelectedWorks of Angelika Kratzer 2009 Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer Available at: https://works.bepress.com/angelika_kratzer/ 6/ Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer This article argues that natural languages have two binding strategies that create two types of bound variable pronouns. Pronouns of the first type, which include local fake indexicals, reflexives, relative pronouns, and PRO, may be born with a ‘‘defective’’ feature set. They can ac- quire the features they are missing (if any) from verbal functional heads carrying standard -operators that bind them. Pronouns of the second type, which include long-distance fake indexicals, are born fully specified and receive their interpretations via context-shifting -operators (Cable 2005). Both binding strategies are freely available and not subject to syntactic constraints. Local anaphora emerges under the assumption that feature transmission and morphophonological spell-out are limited to small windows of operation, possibly the phases of Chomsky 2001. If pronouns can be born underspecified, we need an account of what the possible initial features of a pronoun can be and how it acquires the features it may be missing. The article develops such an account by deriving a space of possible paradigms for referen- tial and bound variable pronouns from the semantics of pronominal features. The result is a theory of pronouns that predicts the typology and individual characteristics of both referential and bound variable pronouns. Keywords: agreement, fake indexicals, local anaphora, long-distance anaphora, meaning of pronominal features, typology of pronouns 1 Fake Indexicals and Minimal Pronouns Referential and bound variable pronouns tend to look the same. -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Scope Or Pseudoscope? Are There Wide-Scope Indefinites?1

1 Scope or Pseudoscope? Are there Wide-Scope Indefinites?1 Angelika Kratzer, University of Massachusetts at Amherst March 1997 1. The starting point: Fodor and Sag My story begins with a famous example by Janet Fodor and Ivan Sag 2: The Fodor and Sag example (1) Each teacher overheard the rumor that a student of mine had been called before the dean. (1) has a reading where the indefinite NP a student of mine has scope within the that - clause. What the teachers overheard might have been: “A student of Angelika’s was called before the dean”. This reading is expected if indefinite NPs are quantifiers, and quantifier scope is confined to some local domain. (1) has another reading where a student of mine seems to have widest scope, scope even wider than each teacher. There might have been a student of mine, say Sanders, and each teacher overheard the rumor that Sanders was called before the dean. Fodor and Sag argue that this is not an instance of scope. If indefinite NPs seem to have anomalous scope properties, they are not true quantifiers. The apparent wide-scope reading of a student of mine in (1) is really a referential reading. Indefinite NPs, then, are ambiguous between quantificational and referential readings. If they are quantificational, their scope cannot exceed some local domain. If they are referential, they do not have scope at all. They may be easily confused with widest scope existentials, however. Sentence (1) is important for Fodor and Sag’s argument since it offers a third scope possibility for the indefinite NP that doesn’t seem to be there. -

Fictionalism Online Companion to Problems of Analytic

FICTIONALISM 2014 EDITION of the ONLINE COMPANION TO PROBLEMS OF ANALYTIC PHILOSOPHY 2012-2015 FCT Project PTDC/FIL-FIL/121209/2010 Edited by João Branquinho and Ricardo Santos ISBN: 978-989-8553-22-5 Online Companion to Problems in Analytic Philosophy Copyright © 2014 by the publisher Centro de Filosofia da Universidade de Lisboa Alameda da Universidade, Campo Grande, 1600-214 Lisboa Fictionalism Copyright © 2014 by the author Fiora Salis All rights reserved Abstract In this entry I will offer a survey of the contemporary debate on fic- tionalism, which is a distinctive anti-realist view about certain regions of discourse that are valued for their usefulness rather than their truth. Keywords Fiction, anti-realism, truth, pretence, figurative language Fictionalism Fictionalism about a region of discourse D is the thesis that utteranc- es of sentences produced within D are, or should be regarded as, akin to utterances of sentences produced within discourse about fiction. Truth is not an essential feature of fictional discourse. Fictions are valued for other reasons. More specifically, the value that they have does not depend on the entities that would have to exist for them to be true. Typically, fictionalism about D is motivated by ontological concerns about such entities. For example, consider the following passage from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five introducing its main character, Billy Pilgrim: Billy was born in 1922 in Ilium, New York, the only child of a bar- ber there. He was a funny-looking child who became a funny-looking youth – tall and weak, and shaped like a bottle of Coca-Cola. -

Quantification, Misc

QUANTIFICATION, MISC. A Dissertation Presented by JAN ANDERSSEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2011 Linguistics c Copyright by Jan Anderssen 2011 All rights reserved QUANTIFICATION, MISC. A Dissertation Presented by JAN ANDERSSEN Approved as to style and content by Angelika Kratzer, Chair Lyn Frazier, Member Christopher Potts, Member Charles Clifton, Jr., Member John J. McCarthy Head of Department Linguistics ACKNOWLEDGMENTS That I have finished this dissertation is in large parts due to the guidance, patience, and encouragement of my committee members. It amazes me how tirelessly they have cleared all the stumbling blocks I sometimes threw in my own way. I am indebted first and foremost to my Doktormutter, Angelika Kratzer. My views on linguistics, and semantics in particular are shaped by Angelika’s writing, teaching, and advising. The introductory classes that I took with Angelika during my visiting year at UMass were the main reason for me to apply there without hesitation. I have never regretted this. What I have learned extends beyond the linguistic horizon. I was fortunate to have an outstanding dissertation committee, and I am very grateful to Lyn Frazier, Chris Potts, and Chuck Clifton for being on my committee, and for being generous with their time and feedback throughout not only the time of my dissertation writing, but the entire time I have known them. That I have enjoyed these years in graduate school no matter how frustrating the work might have seemed at times is entirely due to a great many good friends near and far. -

Lewis on Conventions and Meaning

Lewis on conventions and meaning phil 93914 Jeff Speaks April 3, 2008 Lewis (1975) takes the conventions in terms of which meaning can be analyzed to be conventions of truthfulness and trust in a language. His account may be adapted to state an analysis of a sentence having a given meaning in a population as follows: x means p in a population G≡df (1a) ordinarily, if a member of G utters x, the speaker believes p, (1b) ordinarily, if a member of G hears an utterance of x, he comes to believe p, unless he already believed this, (2) members of G believe that (1a) and (1b) are true, (3) the expectation that (1a) and (1b) will continue to be true gives members of G a good reason to continue to utter x only if they believe p, and to expect the same of other members of G, (4) there is among the members of G a general preference for people to continue to conform to regularities (1a) and (1b) (5) there is an alternative regularity to (1a) and (1b) which is such that its being generally conformed to by some members of G would give other speakers reason to conform to it (6) all of these facts are mutually known by members of G Some objections: • Clause (5) should be dropped, because, as Burge (1975) argued, this clause makes Lewis's conditions on linguistic meaning too strong. Burge pointed out that (5) need not be mutually known by speakers for them to speak a meaningful language. Consider, for example, the case in which speakers believe that there is no possible language other than their own, and hence that there is no alternative regularity to (1a) and (1b).