Bangalore's Toxic Legacy Intensifies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

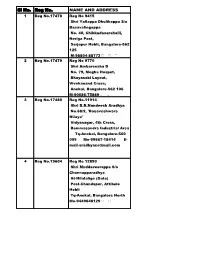

Sl No. Reg No. NAME and ADDRESS 1 Reg No.17478 Reg No 9415 Shri Yallappa Dhulikoppa S/O Basavalingappa No

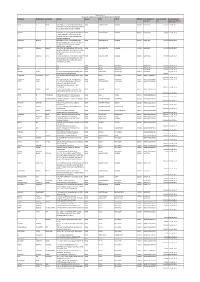

Sl No. Reg No. NAME AND ADDRESS 1 Reg No.17478 Reg No 9415 Shri Yallappa Dhulikoppa S/o Basavalingappa No. 40, Chikkadasarahalli, Neriga Post, Sarjapur Hobli, Bangalore-562 125 M-98804-88772 2 Reg No.17479 Reg No 9770 Shri Ambareesha D No. 79, Megha Hospet, Bhayasabi Layout, Vivekanand Cross, Anekal, Bangalore-562 106 M-90086-75889 3 Reg No.17480 Reg No.11914 Shri B.R.Nandeesh Aradhya No.68/2, 'Basaveshwara Nilaya' Vidyanagar, 4th Cross, Bommasandra Industrial Area Tq-Anekal, Bangalore-560 099 Mo-99867-18414 E- [email protected] 4 Reg No.19604 Reg No 12890 Shri Muddaveerappa S/o Channapparadhya At-Hilalalige (Gate) Post-Chandapur, Attibele Hobli Tq-Anekal, Bangalore North Mo-9449648129 5 Reg No.24386 Reg No 12930 Shri Purushotham Y.R. S/o H.N.Rudramuniyappa Mahadeshwara Stores, H.N.R. Comples, Yadavanahalli Gate Attibele Hobli, Tq-Anekal Bangalore-562107 Mo- 9916970059 6 Reg No.24388 Reg No 12931 Shri Arun Aradhya M S/o Mallikarjuna At & Post-Yadavanahalli-562 107 Attibele Hobli, Tq-Anekal, Bangalore Mo- 9900776813 7 Reg No.27985 Reg No.13438 Shri Sharanabasava Hiremath S/o H.M.Siddaiah S.M.M.Enterprises, Gopalareddy Building Near Canara Computer, Vinayakanagar, Tirupalya Road, Hebbagodi Bangalore-560 099 Mo- 9880545450 8 Reg No.2360 Reg No.13439 Shri Basavaraja Moke S/o Jambanna Moke Sharma Building, Gollahalli Road, Near S.B.I.(ATM) Hebbagodi Bangalore-560 099 Mo-9945975209 9 Reg No.2361 Reg No.13440 Shri Ravi Chandra E S/o Eshwarappa Susheelamma Building, Vinayakanagar Hebbagodi Bangalore-560 099 Mo-9880610078 10 Reg No.11711 Reg No.13441 Shri Veeresh Lalasangi S/o Shivaputrappa NO.52, Balappa Reddy Building Vinayakanagar Hebbagodi Bangalore-560 099 Mo-9739476464 11 Reg No.11712 Reg No.13442 Smt Dhakshayini L.K. -

Geographical Indication Tag

www.gradeup.co Geographical Indication Tag What is Geographical Indication Tag? A geographical indication (GI) is a sign used on products having a particular geographical origin and having qualities or a reputation due to that origin. You might have heard about copyright, patent, trademark, etc. which are rights of intellectual property. Geographical Indication Tag provides holders with similar rights and protection. Darjeeling tea was the first product to be given a GI tag in India. The Geographical Indications of Goods Act was enacted by India in 1999. Why GI tag? India enacted the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Act 1999 as a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), that entered into force with effect from 15 September 2003. It supports local production and helps in mainstreaming and upliftment of the rural and the tribal communities. These GI tags must not be confused with IPR. GI is a collective right, unlike IPRs which grants protection to individual interest. India has registered 236 GI products so far and more than 270 more have applied for the label GI recently got a logo and a tagline given by the Commerce and Industry Minister to increase the awareness about the IPRs in the country. LOGO 1 www.gradeup.co Here we give you an infographic of the most recent addition in the GI list over the past couple of years (2017-2019 Feb) Recently Awarded GI Tag Commodity/handicraft/food Name Place item Konkan (Western Indian states of Maharashtra, Alphonso Food Goa, and the South Indian state of Karnataka) -

Biocon Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014 Tryst and Trust Tryst and Trust Annual Report Biocon Limited 20th KM Hosur Road, Electronic City, Bangalore – 560 100, India T – 91 80 2808 2808 2014 E – corporate.communications@ biocon.com W – www.biocon.com Forward Looking Statement In this Annual Report we have disclosed forward-looking information to enable investors to comprehend our prospects and take informed investment decisions. This report and other statements - written and oral - that we periodically make contain forward-look- ing statements that set out anticipated results based on the management’s plans and assumptions. We have tried wherever possible to identify such statements by using words such as ‘anticipates’, ‘estimates’, ‘expects’, ‘projects’, ‘intends’, ‘plans’, ‘believes’ and words of similar substance in connection with any discussion of future performance. The market data & rankings used in the various chapters are based on several published reports and internal company assessment. We cannot guarantee that these forward looking statements will be realised, although we believe we have been prudent in our assumptions. The achievement of results is subject to risks, uncertainties and even inaccurate assumptions. Should known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialise, or should underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, actual res- ults could vary materially from those anticipated, estimated or projected. Readers should bear this in mind. We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new -

To View BMRCL Annual Report 2019-20

I N D E X 1. Board of Directors ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Notice of AGM ................................................................................................................. 4 3. Chairman’s Speech ........................................................................................................... 6 4. Board’s Report ................................................................................................................. 9 5. Independent Auditor’s Report ....................................................................................... 66 6. Comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India......................................... 82 7. Balance Sheet as at 31st March, 2020............................................................................. 84 8. Statement of Profit and Loss for the year ended 31st March, 2020 ............................... 86 9. Cash Flow Statement for the year ended 31st March, 2020 ........................................... 90 10. Notes to the Financial Statements ................................................................................. 92 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Shri Durga Shanker Mishra Chairman, BMRCL & Secretary - Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India Shri Ajay Seth Managing Director, BMRCL Shri Jaideep Director, BMRCL &OSD (UT) and Ex-Officio Joint Secretary, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India Shri K. K. Saberwal Director, BMRCL -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume: 04, Issue: 04 "April 2019" GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION IN INDIA: CURRENT SCENARIO AND THEIR PRODUCT DISTRIBUTION Swati Sharma Independent Researcher, Gohana, Distt. Sonipat, 131301. ABSTRACT Purpose- The main purpose of this paper is to discuss the concept of geographical indication in India. As geographical indication is an emerging trend and helps us to identify particular goods having special quality, reputation or features originating from a geographical territory. Research methodology- The main objective of the study is to analyze the current scenario and products registered under geographical indication in India during April 2004- March 2019 and discuss state wise, year wise and product wise distribution in India. Secondary data was used for the study and the data was collected from Geographical Indications Registry. Descriptive analysis was used for the purpose of analysis. Findings- The result of present study indicates that Karnataka has highest number of GI tagged products and maximum number of product was registered in the year 2008-09. Most popular product that is registered is handicraft. 202 handicrafts were registered till the date. Implications- The theoretical implications of the study is that it provides State wise distribution, year wise distribution and product wise distribution of GI products in India. This helps the customers as well as producers to make a brand name of that product through origin name. Originality/Value- This paper is one of its kinds which present statistical data of Geographical Indications products in India. Keywords: Geographical Indications, Products, GI tag and Place origin. INTRODUCTION Every geographical region has its own name and goodwill. -

Women Achievers 2011

Women Achievers i TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction iii Message v Foreword vi NEELAM DHAWAN 1 PRIYA CHETTY RAJAGOPAL 2 SUCHITRA K ELLA 4 SUDHA IYER 5 ANURADHA SRIRAM 6 AKILA KRISHNAKUMAR 8 KIRAN MAZUMDAR SHAW 9 DEEPTI REDDY 10 REKHA M MENON 11 REVATHI KASTURI 13 SANDHYA VASUDEVAN 15 Dr VILLOO MORAWALA PATEL 16 AMUKTA MAHAPATRA 18 Dr REKHA SHETTY 19 YESHASVINI RAMASWAMY 21 BEENA KANNAN 23 BINDU ANANTH 24 PARVEEN HAFEEZ 25 MALLIKA SRINIVASAN 26 SUSHMA SRIKANDTH 27 SHEELA KOCHOUSEPH 29 HASTHA KRISHNAN 30 HEMALATHA RAJAN 31 HEMA RAVICHANDAR 32 KAMI NARAYAN 34 UMA RATNAM KRISHNAN 35 SHALINI KAPOOR 37 PREETHA REDDY 38 ii Women Achievers Dr. THARA SRINIVASAN 40 AKHILA SRINIVASAN 42 RAJANI SESHADRI 43 SHOMA BAKRE 44 SANGITA JOSHI 45 GAYATHRI SRIRAM 46 JAYSHREE VENKATRAMAN 48 GEETANJALI KIRLOSKAR 49 KALPANA MARGABHANDU 50 SHARADA SRIRAM 51 SAMANTHA REDDY 53 SHOBHANA KAMINENI 54 VINITA BALI 56 RAJSHREE PATHY . 58 GEETHA VISWANATHAN 59 VALLI SUBBIAH 60 RANJINI MANIAN 62 VANITA MOHAN 63 TILISA GUPTA KAUL 64 SHARAN APPARAO 65 SUNEETA REDDY 66 VANAJA ARVIND 67 Dr. KAMALA SELVARAJ 69 SAKUNTALA RAO 70 NEETA REVANKER 71 MAURA CHARI 73 HAMSANANDHI SESHAN 75 MAHIMA DATLA 77 Dr. NIRMALA LAKSHMAN 78 NANDINI RANGASWAMY 79 PRITHA RATNAM 81 Dr. THARA THYAGARAJAN 82 REVATHY ASHOK 83 SANGITA REDDY 85 GEEHTA PANDA 87 Women Achievers iii INTRODUCTION In the last two decades Indian women have entered work force in large numbers and many of them hold senior positions now Gone are the days when we hardly saw women in lead- ership positions in organizations Some of India’s -

Agricultural and Food

REGISTERED GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS INDIA- AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD S. Application Geographical Goods (As State No No. Indications per Sec 2 (f) of GIG Act 1999 ) 1 143 Guntur Sannam Chilli Agricultural Andhra Pradesh 2 121 Tirupathi Laddu Food stuff Andhra Pradesh 3 433 Bandar Laddu Food Stuff Andhra Pradesh 4 375 Arunachal Orange Agricultural Arunachal Pradesh 5 115 &118 Assam (Orthodox) Agricultural Assam 6 435 Assam Karbi Anglong Agricultural Assam Ginger 7 438 Tezpur Litchi Agricultural Assam 8 439 Joha Rice of Assam Agricultural Assam 9 558 Boka Chaul Agricultural Assam 10 609 Kaji Nemu Agricultural Assam 11 572 Chokuwa Rice of Assam Agricultural Assam 12 551 Bhagalpuri Zardalu Agricultural Bihar 13 553 Katarni Rice Agricultural Bihar 14 554 Magahi Paan Agricultural Bihar 15 552 Shahi Litchi of Bihar Agricultural Bihar 16 584 Silao Khaja Food Stuff Bihar 17 611 Jeeraphool Agricultural Chhattisgarh 18 618 Khola Chilli Agricultural Goa 19 185 Gir Kesar Mango Agricultural Gujarat 20 192 Bhalia Wheat Agricultural Gujarat 21 25 Kangra Tea Agricultural Himachal Pradesh 22 432 Himachali Kala Zeera Agricultural Himachal Pradesh 23 85 Monsooned Malabar Agricultural India Arabica Coffee (Karnataka & Kerala) 24 49 & 56 Malabar Pepper Agricultural India (Kerala, Karnataka & Tamilnadu) 25 385 Nagpur Orange Agricultural India (Maharashtra & Madhya Pradesh) 26 145 Basmati Agricultural India (Punjab / Haryana / Himachal Pradesh / Delhi / Uttarkhand / Uttar Pradesh / Jammu & Kashmir) 27 241 Banaganapalle Mangoes Agricultural India (Telangana & Andhra -

Office of the Additional Director General of Foreign Trade, Bengaluru

OFFICE OF THE ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR GENERAL OF FOREIGN TRADE, BENGALURU EXPORT HOUSE DETAILS FOR THE PERIOD 2015-20 EXPORT HOUSE CERTIFICATES ISSUED IN 2016-17 01 0797003967 HILLTOP STONES PRIVATE LIMITED., 1 Star 2020 A/5911 dtd. NO.1/18,1/19,1/4-1,1/4- 25.04.2016 3,BANNERGHAT TA ROAD,NEAR MICO BACK GATE BANGALORE-560030 02 0788004549 JINDAL ALUMINIUM LTD 2 Star 2020 A/5906 dtd. 16 TH K M TUMKUR ROAD 20.04.2016 BANGALORE -560073 03 0793017289 KARLE INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 2 Star 2020 B/2860 dtd. NO.151, INDL. SUBURB, 19.05.2016 YESHWANTHPUR, BANGALORE- 560022 04 0789009269 ANGLO-FRENCH DRUGS & 1 Star 2020 A/5916 dtd. INDUSTRIES LTD 19.05.2016 41,3RD CRS.BLOCK V, RAJAJINAGAR, BANGALORE-560010 05 0788000250 STERLING FOODS 2 Star 2020 B/2861 dtd. MILAGRES CENTRE,2ND 01.06.2016 FLR.HAMPANKATTA, MANGALORE- 575001 06 0794012094 SREEDEVI CASHEW INDUSTRIES 2 Star 2020 B/2859 dtd. MUDAR, BAJAGOLI, KARKALA TALUK, 19.05.2016 UDUPI, KARNATAKA-574122 07 0388038047 ABB LIMITED 3 Star 2020 C/1622 dtd. BRIGADE GATEWAY CAMPUS, 26/1, 13.05.2016 DR.RAJKUMAR ROAD, MALLESHWARAM, BANGALORE- 560055 08 0788000560 BIOCON LIMITED, 3 Star 2020 JB/0710 dtd. 20TH K M, HOSUR ROAD, 05.04.2016 ELECTRONIC CITY P.O, BANGALORE -560100 09 0700016031 SKF TECHNOLOGIES INDIA PVT LTD 1 Star 2020 A/5907 dtd. PLOT NO.2 BOMMASANDRA INDL 21.04.2016 AREA,BANGALORE -560099 10 0701004461 KENMORE SHOES PVT LTD 2 Star 2020 B/2857 dtd. GOVINDAPURAM MAIN 19.05.2016 ROAD,NAGAWARA BANGALORE-560045 11 0793003580 ARON UNIVERSAL LTD 1 Star 2020 A/5914 dtd. -

Biocon Biologics Joins Hands with IDF in Its Mission to Promote Diabetes Care, Prevention and Effective Management Worldwide”

Biocon Limited 20th KM, Hosur Road Electronic City Bangalore 560 100, India T 91 80 2808 2808 F 91 80 2852 3423 CIN : L24234KA1978PLC003417 www.biocon.com February 16, 2021 To, To, The Manager The Manager BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited Department of Corporate Services Corporate Communication Department Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Exchange Plaza, Bandra Kurla Complex Dalal Street, Mumbai – 400 001 Mumbai – 400 050 Scrip Code – 532523 Scrip Symbol - Biocon Subject: Press Release titled “Biocon Biologics Joins Hands with IDF in its Mission to Promote Diabetes Care, Prevention and effective Management Worldwide”. Dear Sir/Madam, Please find enclosed the press release titled “Biocon Biologics Joins Hands with IDF in its Mission to Promote Diabetes Care, Prevention and effective Management Worldwide”. The above information will also be available on the website of the Company at www.biocon.com. Kindly take the same on record and acknowledge. Thanking You, Yours faithfully, For Biocon Limited _______________ Mayank Verma Company Secretary and Compliance Officer PRESS RELEASE Biocon Biologics Joins Hands with IDF in its Mission to Promote Diabetes Care, Prevention and effective Management Worldwide First Biosimilar Insulin Company to Partner with International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Bengaluru, Karnataka; INDIA: February 16, 2021 Biocon Biologics Ltd., a fully integrated ‘pure play’ biosimilars company and a subsidiary of Biocon Ltd. (BSE code: 532523, NSE: BIOCON), is pleased to partner with The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) as the first biosimilar insulin company to promote and support IDF’s Core Mission initiative and activities. This important partnership with IDF coincides with the start of the centenary celebrations of the discovery of insulin and takes forward Biocon Biologics’ mission of enabling affordable access to insulins to people with diabetes worldwide. -

Adagio Therapeutics Partners with Biocon Biologics to Bring Potent

Adagio Therapeutics Partners with Biocon Biologics to Bring Potent and Broadly Neutralizing COVID-19 Antibody Treatment to Patients in India and Select Emerging Markets Waltham, MA – July 26, 2021 – Adagio Therapeutics, Inc., a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the discovery, development and commercialization of antibody-based solutions for infectious diseases with pandemic potential, today announced a partnership agreement with Biocon Biologics Ltd., to combat the ongoing COVID-19 crisis in southern Asia. Biocon Biologics Ltd. is a fully integrated biosimilars company and a subsidiary of Biocon Ltd., a global biopharmaceuticals company, (BSE code: 532523, NSE: BIOCON). Under the terms of the agreement, Adagio will provide Biocon with materials and know-how to manufacture and commercialize an antibody treatment based on ADG20 in India and additional select emerging markets. ADG20, Adagio’s lead product candidate, is designed to be a potent, long-acting and broadly neutralizing antibody for both the treatment and prevention of COVID-19 as either a single or combination agent. Unlike other antibody-based therapies specifically targeting SARS-CoV-2, ADG20 has demonstrated an ability to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in non-clinical studies, including variants of concern, as well as a broad range of other SARS-like viruses. ADG20 is currently being evaluated in two separate Phase 2/3 global clinical trials, the STAMP trial to evaluate ADG20 for the treatment of non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients and the EVADE trial to evaluate ADG20 for the prevention of COVID-19. “This partnership underscores the commitment of two companies to come together in order to make a significant impact on global health,” said Tillman Gerngross, Ph.D., co-founder and chief executive officer of Adagio. -

Biocon Moves up to Rank No. 6 on Science Careers' Top 20 Global Pharma & Biotech Employers List 2019"

<$Biocon Biocon Limited 20th KM Hosur Road Electronics City Bangalore 560-100, India T 91 80 2808 2808 F 91 80 2852 3423 CIN : L24234KA 1978PLC003417 www.biocon.com October 28, 2019 To To The Manager The Manager, BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited Department of Corporate Services Corporate Communication Department Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Exchange Plaza, Sandra Kurla Complex Dalal Street, Mumbai -400 001 Mumbai- 400 050 Scrip Code - 532523 Scrip Symbol- Biocon Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Press Release Pursuant to Regulation 30 of the SEBI (Listing Obligation and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015, please find enclosed the press release titled "Biocon Moves Up to Rank No. 6 on Science Careers' Top 20 Global Pharma & Biotech Employers list 2019". The above information will also be available on the website of the Company at www.biocon.com. Kindly take the same on record and acknowledge. Thanking You, Yours faithfully, For Biocon Li mited Mayank Verma Company Secretary & Compliance Officer Enclosed: Pre ss Release Press Release Biocon Moves Up to Rank No. 6 on Science Careers’ Top 20 Global Pharma & Biotech Employers List 2019 Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, October 28, 2019 Biocon Ltd, an innovation-led global biopharmaceuticals company, has moved up in the Top 10 Global Biotech Employers ranking for 2019 and continues to be the only Company from Asia to feature on the prestigious U.S.-based Science magazine’s annual ‘Science Careers Top 20 Employers’ list, since its debut in 2012. Ranked at No. 6 among global pharma and biotech companies in 2019, Biocon has moved up from No. -

Proposed Date of Securities Rs.) Transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid final dividend for FY 2007-08 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Due(in Proposed Date of Securities Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 250.00 22-AUG-2015 CAP MARK SERV PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 250.00 22-AUG-2015 CAPITAL MKT SER C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 250.00 22-AUG-2015 HEAD CAP MARK SERV CPU PL 82/83 RD 7 ST 15 OPP SPECAILITY RANBAXY LAB MIDC ANDHERI EAST MUMBAI URMILA LAXMAN SAWANT C/O KOTAK MAHINDRA BANK LTD VINAYA INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400098 BIO043838 250.00 22-AUG-2015 BHAVYA COMPLEX 5TH FLR 159-A CST ROAD KALINA SANTACRUZ E MUMBAI PHONE- 56768300 NEHA KAMLESH SHAH G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MARKET INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043408 250.00 22-AUG-2015 SERVISES CENTRAL PROCESSING UNIT PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 5 MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054733 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054734 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054748 250.00 22-AUG-2015 MANISH SALNI NO 305 GOLF MANOR WIND TUNNEL ROAD INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560017 BIO038066 22-AUG-2015 MURUGESHPALYA BANGALORE 250.00 Madhubani Investments P Ltd G 16 Marina Arcade Connaught Circus New INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110001 IN30177410005267 Delhi 4250.00 22-AUG-2015 VANDANA GOGIA HOUSE NO.904 SECTOR-28 FARIDABAD INDIA HARYANA FARIDABAD 121002 IN30209210046456 2500.00 22-AUG-2015 GEETA SINGH C/O JITENDRA PRATAP SINGH RESIDENT INDIA UTTAR PRADESH SULTANPUR 228001 IN30055610009786 ENGINEER TEMPORARY DEPART.