(NR3C1) Locus Was Modified by Standard Gene Targeting Procedures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The G Protein-Coupled Receptor Subset of the Dog Genome Is More Similar

BMC Genomics BioMed Central Research article Open Access The G protein-coupled receptor subset of the dog genome is more similar to that in humans than rodents Tatjana Haitina1, Robert Fredriksson1, Steven M Foord2, Helgi B Schiöth*1 and David E Gloriam*2 Address: 1Department of Neuroscience, Functional Pharmacology, Uppsala University, BMC, Box 593, 751 24, Uppsala, Sweden and 2GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, New Frontiers Science Park, 3rd Avenue, Harlow CM19 5AW, UK Email: Tatjana Haitina - [email protected]; Robert Fredriksson - [email protected]; Steven M Foord - [email protected]; Helgi B Schiöth* - [email protected]; David E Gloriam* - [email protected] * Corresponding authors Published: 15 January 2009 Received: 20 August 2008 Accepted: 15 January 2009 BMC Genomics 2009, 10:24 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-24 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/10/24 © 2009 Haitina et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: The dog is an important model organism and it is considered to be closer to humans than rodents regarding metabolism and responses to drugs. The close relationship between humans and dogs over many centuries has lead to the diversity of the canine species, important genetic discoveries and an appreciation of the effects of old age in another species. The superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is one of the largest gene families in most mammals and the most exploited in terms of drug discovery. -

Genetic Basis of Idiopathic Scoliosis

Research & Review: Management of Cardiovascular and Orthopedic Complications Volume 1 Issue 1 Genetic Basis of Idiopathic Scoliosis S. Sreeremya Assistant Professor, Department of Biotechnology, Sree Narayana Guru College, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Email: [email protected] Abstract Idiopathic scoliosis (IS), the most usual spinal deformity, affects otherwise healthy children and adolescents during growth. The etiology is still not quiet understood, although genetic factors are believed to be important. This review corroborates the understanding of IS as a complex disease with a polygenic background. Presumably IS can be typically due to a spectrum of genetic risk variants, ranging from very rare or even private to very common. The most promising candidate genes are highlighted. Keywords: Idiopathic scoliosis, Genetics, Pathogenesis, Heredity INTRODUCTION marked by phenotypic complexity Idiopathic scoliosis (IS), the most general (variations in curve morphology and form of spinal deformity, affects otherwise magnitude, age of onset, rate of healthy children and adolescents during progression), and a prognosis mainly growth (Fig: 1). It usually presents as a rib ranging from increase in curve magnitude, hump visible at forward bending, together to stabilization, or to resolution with with unlevelled shoulders and an growth [5]. Genetic factors are known to asymmetrical waist [1]. According to play a pivotal role, as observed in twin Cobb, the diagnosis is specifically studies and their observation and singleton confirmed by a standing spinal radiograph multigenerational families [6]. A recent showing a lateral curvature of the spine research of monozygotic and dizygotic exceeding 10° [2]. A main concern in IS is twins from the Swedish twin registry the absence of reliable means by which to estimated that overall genetic effects predict risk of progression, leading to accounted for 39 % of the observed frequent follow-ups, radiographs, and phenotypic variance, leaving the remaining potentially unnecessary brace treatments. -

The Neuroprotective Effects of Melatonin: Possible Role in the Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Disease

brain sciences Perspective The Neuroprotective Effects of Melatonin: Possible Role in the Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Disease Jung Goo Lee 1,2 , Young Sup Woo 3, Sung Woo Park 2,4, Dae-Hyun Seog 5, Mi Kyoung Seo 6 and Won-Myong Bahk 3,* 1 Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Haeundae Paik Hospital, Inje University, Busan 47392, Korea; [email protected] 2 Paik Institute for Clinical Research, Department of Health Science and Technology, Graduate School, Inje University, Busan 47392, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul 07345, Korea; [email protected] 4 Department of Convergence Biomedical Science, College of Medicine, Inje University, Busan 47392, Korea 5 Department of Biochemistry, College of Medicine, Inje University, Busan 47392, Korea; [email protected] 6 Paik Institute for Clinical Research, Inje University, Busan 47392, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 September 2019; Accepted: 19 October 2019; Published: 21 October 2019 Abstract: Melatonin is a hormone that is secreted by the pineal gland. To date, melatonin is known to regulate the sleep cycle by controlling the circadian rhythm. However, recent advances in neuroscience and molecular biology have led to the discovery of new actions and effects of melatonin. In recent studies, melatonin was shown to have antioxidant activity and, possibly, to affect the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In addition, melatonin has neuroprotective effects and affects neuroplasticity, thus indicating potential antidepressant properties. In the present review, the new functions of melatonin are summarized and a therapeutic target for the development of new drugs based on the mechanism of action of melatonin is proposed. -

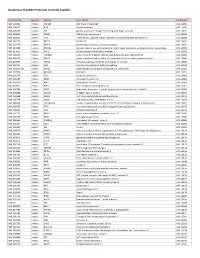

Quantigene Flowrna Probe Sets Currently Available

QuantiGene FlowRNA Probe Sets Currently Available Accession No. Species Symbol Gene Name Catalog No. NM_003452 Human ZNF189 zinc finger protein 189 VA1-10009 NM_000057 Human BLM Bloom syndrome VA1-10010 NM_005269 Human GLI glioma-associated oncogene homolog (zinc finger protein) VA1-10011 NM_002614 Human PDZK1 PDZ domain containing 1 VA1-10015 NM_003225 Human TFF1 Trefoil factor 1 (breast cancer, estrogen-inducible sequence expressed in) VA1-10016 NM_002276 Human KRT19 keratin 19 VA1-10022 NM_002659 Human PLAUR plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor VA1-10025 NM_017669 Human ERCC6L excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 6-like VA1-10029 NM_017699 Human SIDT1 SID1 transmembrane family, member 1 VA1-10032 NM_000077 Human CDKN2A cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (melanoma, p16, inhibits CDK4) VA1-10040 NM_003150 Human STAT3 signal transducer and activator of transcripton 3 (acute-phase response factor) VA1-10046 NM_004707 Human ATG12 ATG12 autophagy related 12 homolog (S. cerevisiae) VA1-10047 NM_000737 Human CGB chorionic gonadotropin, beta polypeptide VA1-10048 NM_001017420 Human ESCO2 establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 2 (S. cerevisiae) VA1-10050 NM_197978 Human HEMGN hemogen VA1-10051 NM_001738 Human CA1 Carbonic anhydrase I VA1-10052 NM_000184 Human HBG2 Hemoglobin, gamma G VA1-10053 NM_005330 Human HBE1 Hemoglobin, epsilon 1 VA1-10054 NR_003367 Human PVT1 Pvt1 oncogene homolog (mouse) VA1-10061 NM_000454 Human SOD1 Superoxide dismutase 1, soluble (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 1 (adult)) -

Genetic Variations of Melatonin Receptor Type 1A Are Associated with the Clinicopathologic Development of Urothelial Cell Carcin

Int. J. Med. Sci. 2017, Vol. 14 1130 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Medical Sciences 2017; 14(11): 1130-1135. doi: 10.7150/ijms.20629 Research Paper Genetic Variations of Melatonin Receptor Type 1A are Associated with the Clinicopathologic Development of Urothelial Cell Carcinoma Yung-Wei Lin1, 2, Shian-Shiang Wang3, 4, 5, Yu-Ching Wen2, 6, Min-Che Tung1, 7, Liang-Ming Lee2, 6, Shun-Fa Yang5, 8, Ming-Hsien Chien1, 9 1. Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan; 2. Department of Urology, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan; 3. Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 4. School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; 5. Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; 6. Department of Urology, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan; 7. Department of Surgery, Tungs' Taichung Metro Harbor Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 8. Department of Medical Research, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 9. Department of Medical Education and Research, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan. Corresponding authors: Ming-Hsien Chien, PhD, Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, Taipei Medical University, 250 Wu-Hsing Street, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; Phone: 886-2-27361661, ext. 3237; Fax: 886-2-27390500; E-mail: [email protected] or Shun-Fa Yang, PhD, Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, 110 Chien-Kuo N. Road, Section 1, Taichung 402, Taiwan; Phone: 886-4-2473959, ext. 34253; Fax: 886-4-24723229; E-mail: [email protected] © Ivyspring International Publisher. -

The Role of Melatonin in Diabetes: Therapeutic Implications

review The role of melatonin in diabetes: therapeutic implications Shweta Sharma1, Hemant Singh1, Nabeel Ahmad2, Priyanka Mishra1, Archana Tiwari1 ABSTRACT Melatonin referred as the hormone of darkness is mainly secreted by pineal gland, its levels being 1 School of Biotechnology, Rajiv elevated during night and low during the day. The effects of melatonin on insulin secretion are me- Gandhi Technical University, Gandhi diated through the melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2). It decreases insulin secretion by inhibiting Nagar, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh cAMP and cGMP pathways but activates the phospholipaseC/IP3 pathway, which mobilizes Ca2+ from 2 School of Biotechnology, organelles and, consequently increases insulin secretion. Both in vivo and in vitro, insulin secretion IFTM University, Lodhipur Rajput, Uttar Pradesh by the pancreatic islets in a circadian manner, is due to the melatonin action on the melatonin recep- tors inducing a phase shift in the cells. Melatonin may be involved in the genesis of diabetes as a Correspondence to: reduction in melatonin levels and a functional interrelationship between melatonin and insulin was Shweta Sharma School of Biotechnology observed in diabetic patients. Evidences from experimental studies proved that melatonin induces Rajiv Gandhi Technical University production of insulin growth factor and promotes insulin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation. The dis- Airport Bypass Road, Gandhi Nagar turbance of internal circadian system induces glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, which could 462036 – Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh [email protected] be restored by melatonin supplementation. Therefore, the presence of melatonin receptors on hu- man pancreatic islets may have an impact on pharmacotherapy of type 2 diabetes. Arch Endocrinol Metab. Received on June/8/2015 2015;59(5):391-9 Accepted on July/6/2015 DOI: 10.1590/2359-3997000000098 Keywords Melatonin; diabetes; insulin; beta cells; calcium; circadian rhythm INTRODUCTION tomy of rodents causes hyperinsulinemia (7). -

Neurotransmission Alphabetical 28/7/05 15:52 Page 1

neuroscience - Neurotransmission alphabetical 28/7/05 15:52 Page 1 Abcam’s range of Neuroscience receptor, channel and ligand antibodies includes over 320 tried and tested products www.abcam.com Neurotransmission - receptor and channel signaling www.abcam.com GPCRs TYROSINE KINASES ION CHANNELS Neurotrophins rin u BDNF rt NGF u NT-3 Glutamate GABA ACh GDNF Ne Artemin Persepin NT-4/5 Glutamate Anandamide ATP Glycine ␥ 2-AG 1 2 3 4 / ␣ ␣ ␣ ␣ R / u A GFR GFR GFR GFR NTR mGL X1, 2, 3 CB1/2 2 EphA/B* Ephrin RET TrkA/B/C p75 AMPA/KainateNMDAR P GABA GlyR nAChR IP3 released Lyn Ephexin Homer DAG Adenylate Fyn PI3K Gr Src PSD95 Rapsin i PD2RGS3 Shc Syntrophin b K PLC Gi/q cyclase Gi 4 NcK PI3 Shc + 2+ 2+ PI3K PLC ␥ Na Ca Ca P PI3K Grb2 PLC/␥ PKC nNOS ␥ FAK PiP3/4 SOS MEK CaM Cl- Cl- ER NFkB PDEI PKA Rac RhoA RasGAP Src PTEN PKC Ras GTPase ERK CaMK 2+ PKK2 Calcineurin Ca released ROCK ERK FRS2 AKT/PKB Raf JNK nNOS SynGAP Grb2 actin MEK 1/2 P Ser133 Inhibition Cl- Src SOS Cell survival CREB of signaling RAS P CREB ERK 1/2 P P MAPK GSK3 ELK RSK NFB CREB CREB gene Long term Cytoskeleton transcription synaptic dynamics, neurite ASK1 Bad CRE plasticity (LTP) P P extension CREB CREB Short term MKK3/6 Apoptosis plasticity Others Other GPCRs - ARA9 ACh (Muscarinic): M1, M2, M3, M4 CRE p38MAPK c-fos Potassium - ASIC, ASIC3 Adrenalin: Alpha1b, 1c, 1d - KChIP2 - DDR 1, 2 ATP: P2Y MSK1 c-j c-fos gene - KCNQ 3, 5 - ENSA Dopamine: D1, D4 u transcription - Kv beta 2 - GJB1 n GABA: GABAB receptor - Kv 1.2 - SLC31A1 ␦ P P Opioid: µ, , CREB CREB AP1 - Kv -

WO 2012/174282 A2 20 December 2012 (20.12.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/174282 A2 20 December 2012 (20.12.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: David [US/US]; 13539 N . 95th Way, Scottsdale, AZ C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) 85260 (US). (21) International Application Number: (74) Agent: AKHAVAN, Ramin; Caris Science, Inc., 6655 N . PCT/US20 12/0425 19 Macarthur Blvd., Irving, TX 75039 (US). (22) International Filing Date: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 14 June 2012 (14.06.2012) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, English (25) Filing Language: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, Publication Language: English DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (30) Priority Data: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, 61/497,895 16 June 201 1 (16.06.201 1) US MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 61/499,138 20 June 201 1 (20.06.201 1) US OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, 61/501,680 27 June 201 1 (27.06.201 1) u s SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, 61/506,019 8 July 201 1(08.07.201 1) u s TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially Expressed Genes following Sham treatment relative to Untreated Controls Fold Change Accession Name Symbol 3 h 12 h NM_013121 CD28 antigen Cd28 12.82 BG665360 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 Flt1 9.63 NM_012701 Adrenergic receptor, beta 1 Adrb1 8.24 0.46 U20796 Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 Nr1d2 7.22 NM_017116 Calpain 2 Capn2 6.41 BE097282 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 6.21 NM_053328 Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 Bhlhb2 5.79 NM_053831 Guanylate cyclase 2f Gucy2f 5.71 AW251703 Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a Tnfrsf12a 5.57 NM_021691 Twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) Twist2 5.42 NM_133550 Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide Fcer2a 4.93 NM_031120 Signal sequence receptor, gamma Ssr3 4.84 NM_053544 Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 Sfrp4 4.73 NM_053910 Pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled/coil domains 1 Pscd1 4.69 BE113233 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 Socs2 4.68 NM_053949 Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag- Kcnh2 4.60 related), member 2 NM_017305 Glutamate cysteine ligase, modifier subunit Gclm 4.59 NM_017309 Protein phospatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha Ppp3r1 4.54 isoform,type 1 NM_012765 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C Htr2c 4.46 NM_017218 V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog Erbb3 4.42 3 (avian) AW918369 Zinc finger protein 191 Zfp191 4.38 NM_031034 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 4.38 NM_017020 Interleukin 6 receptor Il6r 4.37 AJ002942 -

Enhancer Rnas: Transcriptional Regulators and Workmates of Namirnas in Myogenesis

Odame et al. Cell Mol Biol Lett (2021) 26:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-021-00248-x Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters REVIEW Open Access Enhancer RNAs: transcriptional regulators and workmates of NamiRNAs in myogenesis Emmanuel Odame , Yuan Chen, Shuailong Zheng, Dinghui Dai, Bismark Kyei, Siyuan Zhan, Jiaxue Cao, Jiazhong Guo, Tao Zhong, Linjie Wang, Li Li* and Hongping Zhang* *Correspondence: [email protected]; zhp@sicau. Abstract edu.cn miRNAs are well known to be gene repressors. A newly identifed class of miRNAs Farm Animal Genetic Resources Exploration termed nuclear activating miRNAs (NamiRNAs), transcribed from miRNA loci that and Innovation Key exhibit enhancer features, promote gene expression via binding to the promoter and Laboratory of Sichuan enhancer marker regions of the target genes. Meanwhile, activated enhancers pro- Province, College of Animal Science and Technology, duce endogenous non-coding RNAs (named enhancer RNAs, eRNAs) to activate gene Sichuan Agricultural expression. During chromatin looping, transcribed eRNAs interact with NamiRNAs University, Chengdu 611130, through enhancer-promoter interaction to perform similar functions. Here, we review China the functional diferences and similarities between eRNAs and NamiRNAs in myogen- esis and disease. We also propose models demonstrating their mutual mechanism and function. We conclude that eRNAs are active molecules, transcriptional regulators, and partners of NamiRNAs, rather than mere RNAs produced during enhancer activation. Keywords: Enhancer RNA, NamiRNAs, MicroRNA, Myogenesis, Transcriptional regulator Introduction Te identifcation of lin-4 miRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans in 1993 [1] triggered research to discover and understand small microRNAs’ (miRNAs) mechanisms. Recently, some miRNAs are reported to activate target genes during transcription via base pairing to the 3ʹ or 5ʹ untranslated regions (3ʹ or 5ʹ UTRs), the promoter [2], and the enhancer regions [3]. -

Sex-Specific Transcriptome Differences in Human Adipose

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Sex-Specific Transcriptome Differences in Human Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells 1, 2, 3 1,3 Eva Bianconi y, Raffaella Casadei y , Flavia Frabetti , Carlo Ventura , Federica Facchin 1,3,* and Silvia Canaider 1,3 1 National Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Stem Cell Bioengineering of the National Institute of Biostructures and Biosystems (NIBB)—Eldor Lab, at the Innovation Accelerator, CNR, Via Piero Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (E.B.); [email protected] (C.V.); [email protected] (S.C.) 2 Department for Life Quality Studies (QuVi), University of Bologna, Corso D’Augusto 237, 47921 Rimini, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Experimental, Diagnostic and Specialty Medicine (DIMES), University of Bologna, Via Massarenti 9, 40138 Bologna, Italy; fl[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-051-2094114 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 6 August 2020; Published: 8 August 2020 Abstract: In humans, sexual dimorphism can manifest in many ways and it is widely studied in several knowledge fields. It is increasing the evidence that also cells differ according to sex, a correlation still little studied and poorly considered when cells are used in scientific research. Specifically, our interest is on the sex-related dimorphism on the human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) transcriptome. A systematic meta-analysis of hMSC microarrays was performed by using the Transcriptome Mapper (TRAM) software. This bioinformatic tool was used to integrate and normalize datasets from multiple sources and allowed us to highlight chromosomal segments and genes differently expressed in hMSCs derived from adipose tissue (hADSCs) of male and female donors. -

Prognostic Impact of Melatonin Receptors MT1 and MT2 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

Article Prognostic Impact of Melatonin Receptors MT1 and MT2 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Karolina Jablonska 1,*, Katarzyna Nowinska 1, Aleksandra Piotrowska 1, Aleksandra Partynska 1, Ewa Katnik 1, Konrad Pawelczyk 2,3 Alicja Kmiecik 1, Natalia Glatzel-Plucinska 1, Marzenna Podhorska-Okolow 4 and Piotr Dziegiel 1,5 1 Division of Histology and Embryology, Department of Human Morphology and Embryology, Wroclaw Medical University, 50-368 Wroclaw, Poland 2 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Wroclaw Medical University, 53-439 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Lower Silesian Centre of Lung Diseases, 53-439 Wroclaw, Poland 4 Division of Ultrastructure Research, Wroclaw Medical University, 50-368 Wroclaw, Poland 5 Department of Physiotherapy, University School of Physical Education, 51-612 Wroclaw, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel: +48-717841680; Fax: +48-717840082 Received: 14 May 2019; Accepted: 15 July 2019; Published: 17 July 2019 Abstract: Background: Several studies have investigated the inhibitory effect of melatonin on lung cancer cells. There are no data available on the prognostic impact of melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Materials and Methods: Immunohistochemical studies of MT1 and MT2 were conducted on NSCLC (N = 786) and non-malignant lung tissue (NMLT) (N = 120) using tissue microarrays. Molecular studies were performed on frozen fragments of NSCLC (N = 62; real time PCR), NMLT (N = 24) and lung cancer cell lines NCI-H1703, A549 and IMR-90 (real time PCR, western blot). Results: The expression of both receptors was higher in NSCLC than in NMLT. Higher MT1 and MT2 expression levels (at protein and mRNA) were noted in squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) compared to adenocarcinomas (AC).