Cathedral Thinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Immediate Release Contact: Jonathon [email protected] ARTIST CREATES NEW UNIVERSE from URANIUM and CHEWING GUM Novel Technique

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected] ARTIST CREATES NEW UNIVERSE FROM URANIUM AND CHEWING GUM Novel Technique Puts Quantum Theory to Practical Use. Automated Universe Factories Planned for Government and Industry. San Francisco Gallery to Begin Selling $20 D.I.Y. Universe Kits on November 20th. Universes Provide Alternatives to Recession October 31, 2008 - Following decades of effort by engineers to build quantum supercomputers and to master quantum cryptography, today quantum physics has spawned a far more powerful technology. Applying theory developed by deceased Princeton physicist Hugh Everett III, and using little more than a piece of chewing gum, a plastic drinking straw, and a bit of uranium, San Francisco conceptual artist Jonathon Keats has constructed the first machine for fabricating all-inclusive universes. "It was a product of my anxiety," admits Mr. Keats. "I'd recently had a couple museum shows, yet I was feeling that no matter what I made, it was hardly comparable to the creation of the cosmos. And though no one talks about it, the same issue faced Picasso, Monet, even Michelangelo. The Big Bang has artists beat." Taking on the cosmos as a creative challenge, Mr. Keats began researching an aspect of quantum mechanics proposed by Dr. Everett in the 1950s and later refined by scientists including David Deutsch at Oxford and Wojciech Zurek at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Dr. Everett's theory addressed the question of how a subatomic particle can exist in a quantum superposition - for example being in two places at once - until someone observes it, at which point the observer finds it to be in only one place at a time. -

Download CV (PDF)

Anuradha Vikram anu(at)curativeprojects(dot)net About Anuradha (Curative Projects) Independent curator and scholar working with museums, galleries, journals, and websites to develop original curatorial work including exhibitions, public programs, and artist-driven publications. Consultant for strategic planning, institutional vision, content strategy, and diversity, equity, and inclusion work. Current engagements include Craft Contemporary, LA Freewaves, MhZ Curationist, LACE, X-TRA, X Artists’ Books, and UCLA Art Sci Center. Education M.A., Curatorial Practice, California College of the Arts, San Francisco, CA, 2005 B.S., Studio Art, minor in Art History, New York University, New York, NY, 1997 Curated Exhibitions, Performances, and Public Art 2024 ▪ Co-curator, Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption (with Victoria Vesna), UCLA Art Sci Center at Center for Art of Performance, Getty Pacific Standard Time: Art x Science x LA, dates TBC. 2023 ▪ Unmaking/Unmarking: Archival Poetics and Decolonial Monuments, LACE, Los Angeles, dates TBC. 2022 ▪ Jaishri Abichandani: Lotus-Headed Children, Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles, CA, January 30–May 8. ▪ Exa(men)ing Masculinities, with Marcus Kuiland-Nazario and Anne Bray, LA Freewaves, Los Angeles State Historic Park, dates TBC. 2021 ▪ Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption, Ars Electronica 2021 Garden, September 8-12. ▪ Juror, FRESH 2021, SoLA Contemporary. August 28-October 9. 2020 ▪ Patty Chang: Milk Debt, 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica, CA, October 19-January 22, 2021. Traveled to PioneerWorks, Brooklyn, March 19-May 23, 2021. ▪ Co-curator, Drive-By-Art (with Warren Neidich, Renee Petropoulos, and Michael Slenske). Citywide exhibition, Los Angeles, May 23-31. -

2013 Lyndenstoneleonardo46 5

G e n e r a l a r t I c l e Re-Visioning Reality: Quantum Superposition in Visual Art a b s t r a c t The counterintuitive phenom- enon of quantum superposition requires a radical review of our ideas of reality. The author Lynden Stone suggests that translations of quantum concepts into visual art may assist in provoking such a revision. This essay first introduces the concept n philosophy, the usual definition of conven- a radical departure from the clas- of quantum superposition and I points out its divergence from tional reality is that it is independent, objective, meaningful sical conception of the fabric of and, in principle, knowable [1]; I adopt this definition for the reality” [7], and Karen Barad states conventional perceptions of real- ity. The author then discusses purpose of this article. My experience of reality generally ac- that we need a “reassessment of how visual art might provide cords with this definition, insofar as I perceive objects to exist physical and metaphysical notions insight into quantum superposi- independently of me and that objects have predetermined that explicitly or implicitly rely on tion. Finally she discusses the characteristics that are independent of whatever observations old ideas about the physical world” visual representation of quantum or measurements I might perform on them. In particular, I can superposition by contemporary [8]. Trying to understand a world artists Jonathon Keats, Julian unobtrusively observe and measure objects without affecting described by quantum theory, says Voss-Andreae, Antony Gormley their state or the dynamics of the system within which they philosopher Lawrence Sklar, re- and Daniel Crooks; the problem- exist. -

Mccray CV Full Version

W. PATRICK MCCRAY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA SANTA BARBARA, CA 93106-9410 CURRENT APPOINTMENTS Professor, Department of History, University of California at Santa Barbara Affiliate appointments at University of California at Santa Barbara: Global Studies Program; Media Arts and Technology Program EDUCATION University of Arizona, Ph.D. (December 1996), Materials Science and Engineering with Anthropology (minor), Dissertation topic – Glassmaking in Renaissance Venice. University of Pittsburgh, M.S. (1991), B.S. (1989), Materials Science and Engineering. SELECTED OTHER APPOINTMENTS 2015-2016 Lindbergh Chair, National Air & Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. 2011-2012 Eleanor Searle Visiting Professor, California Institute of Technology 2005-2007 Associate Professor, History Department, UCSB. 2005-2007 Co-Director of Center for Nanotechnology in Society at UCSB 2003-2005 Assistant Professor, Department of History, UCSB 2000-2003 Associate Historian; Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics 1999-2000 Research Fellow, Department of History, The George Washington University 1997-1999 Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Arizona MAJOR AWARDS, AND HONORS Invited Faculty Expert, World Economic Forum (Davos, Switzerland), 2016. Watson Davis and Helen Miles Davis Prize, History of Science Society, 2014. Fellow, American Physical Society, elected 2013. Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science, elected 2011. BOOKS & EDITED VOLUMES Groovy Science: Knowledge, Innovation, and the American Counterculture, co-edited with David Kaiser (The University of Chicago Press, 2016). The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future (Princeton University Press, 2013). Winner: Watson Davis and Helen Miles Davis Prize, History of Science Society, 2014; Eugene M. Emme Astronautical Literature Award, American Astronautical Society, 2013. -

Mr. Edward F. Sproat III Director Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management United States Department of Energy Washington, DC 20585

5.)6%23%35.,)-)4%$ v v 00-!+).'.%77/2,$33).#% Mr. Edward F. Sproat III Director Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management United States Department of Energy Washington, DC 20585 November 19, 2008 Dear Mr. Edward F. Sproat III, It has recently come to our attention that you’re planning to build the nation’s largest nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain in the State of Nevada. Please first allow us to extend our congratulations to you and your team. We are impressed by the scope of your ambition. It is clear that your governmental division, the Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management, United States Department of Energy, is particularly farsighted. Second, we want to offer our services, which we can state with confidence are uniquely suited to your special project. Universes Unlimited is the foremost purveyor of equipment for macrocosmic fabrication. Our quantum decoherence engine is the only machine purpose-built for all-encompassing creation. On behalf of government and industry, we design state-of-the-art factories to mass-produce full-scale universes. And we are pleased to inform you that the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository is a premier site for the largest universe factory in the world. You should know that your planned facility need be modified only slightly to serve this valuable secondary purpose. Because our quantum decoherence engines are atomic, a universe factory can recycle your unwanted gamma rays, as well as your decaying alpha and beta particles. In other words, Mr. Edward F. Sproat III, your nuclear waste need not go to waste. -

Press Release: the New Look of Neuroscience

For Immediate Release contact: [email protected] NEW WEARABLE TECHNOLOGIES BIOCHEMICALLY OPTIMIZE WEARERS' PERSONALITIES Fashion-Forward 'Superego Suits' Developed By Jonathon Keats At The LACMA Art + Technology Lab Will Debut In San Francisco This March February 27, 2017 – Applying cutting-edge neuroscience to millennia of costume history, a multidisciplinary research initiative has achieved simultaneous breakthroughs in both fields, pioneering the next generation of wearable technology. Building on research from laboratories at Harvard and Florida State University, experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats will introduce 'Superego Suits' to the public in San Francisco next month. Fully modular and customizable to all body types, Superego Suits boast multiple features to alter self- perception, augmenting wearers' personalities for work and social life. "Today's wearables can supplement wearers' memories and knowledge and interactivity by connecting them to the internet," says Mr. Keats. "But psychologically you still remain your same old self. Glassholes will be Glassholes." Superego Suits get to the root of the problem by altering biochemistry and brain/body communication. They can make wearers more confident and enchanting, and even connect with other Superego Suits to manage interpersonal relationships. Four major innovations will be showcased at San Francisco's Modernism Gallery, where prototypes will be on view together with fashion photography by Elena Dorfman, featuring the Wilhelmina International model Anna Sophia Moltke. Mr. Keats has engineered sunglasses with irises designed to open and close in time with the wearer's breathing – augmenting her presence by increasing awareness of her internal state – a phenomenon known in neuroscience as interoception. He's also developed bracelets that can position the wearer in a 'power pose', causing the release of testosterone, a hormone associated with self-assurance. -

Cosmic Mat Welcomes Aliens 27 October 2017, by Glenda Kwek

One small doorstep for man: Cosmic mat welcomes aliens 27 October 2017, by Glenda Kwek gallery on Friday. "I have been fascinated by Fermi's Paradox: if there's intelligent life throughout the universe, where is everybody?," Keats, also a conceptual artist, told AFP at the recent International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide. "I started thinking about how we might be perceived by beings elsewhere in the universe. It struck me that we really might not be seen as being especially friendly." Fermi's Paradox is named after Italian-born It may look like an ordinary door mat, but its creators insist the conceptual art piece could encourage alien life physicist Enrico Fermi, the 1938 Nobel laureate to visit Earth—and help create a new kind of space who created the first controlled nuclear chain archaeology reaction. His 1950 question "Where is everybody?" has since sparked debate about the contradiction between It may look like an ordinary door mat, but its the probability of extraterrestrial civilisations and creators insist the conceptual art piece could why humans have not encountered them. encourage alien life to visit Earth—and help create a new kind of space archaeology. 'The ultimate alien' Dubbed the "Cosmic Welcome Mat" it features Gorman said another benefit to the project would swirls of red, sky blue, and violet against a black be that some of the dust the mats accumulate border, and is meant to convey a warm reception would be from outer space. to all sentient life in the universe. "Because there's about 40,000 tons (36,300 Experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats, who tonnes) of extraterrestrial material that falls to the created the rug with space archaeologist Alice surface of the Earth every year, we know there'll be Gorman of Flinders University in Australia, aims to a cosmic component to the dust," she explained. -

Charles Darwin

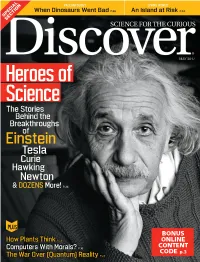

MAY 2017 Heroes of Science The Stories Behind the Breakthroughs Einstein of Tesla Curie Hawking Newton & DOZENS More! P.34 PLUS BONUS How Plants Think P.52 ONLINE CONTENT Computers With Morals? P.10 CODE p.3 The War Over (Quantum) Reality P.28 The Theory of Everything: The Quest to Explain All Reality TIME ED O Taught by Professor Don Lincoln T FF I E FERMI NATIONAL ACCELERATOR LABORATORY IM R L 70% LECTURE TITLES 1. Two Prototype Theories of Everything off 2. The Union of Electricity and Magnetism 1 O 3 3. Particles and Waves: The Quantum World R D AY ER BY M 4. Einstein Unifi es Space, Time, and Light 5. Relativistic Quantum Fields and Feynman 6. Neutrinos Violating Parity and the Weak Force 7. Flavor Changes via the Weak Force 8. Electroweak Unifi cation via the Higgs Field 9. Quarks, Color, and the Strong Force 10. Standard Model Triumphs and Challenges 11. How Neutrino Identity Oscillates 12. Conservation Laws and Symmetry: Emmy Noether 13. Theoretical Symmetries and Mathematics 14. Balancing Force and Matter: Supersymmetry 15. Why Quarks and Leptons? 16. Newton’s Gravity Unifi es Earth and Sky 17. Einstein’s Gravity Bends Space-Time 18. What Holds Each Galaxy Together: Dark Matter 19. What Pushes the Universe Apart: Dark Energy 20. Quantum Gravity: Einstein, Strings, and Loops 21. From Weak Gravity to Extra Dimensions 22. Big Bang and Infl ation Explain Our Universe 23. Free Parameters and Other Universes Pick Up the Quest 24. Toward a Final Theory of Everything Where Einstein Failed The Theory of Everything: At the end of his career, Albert Einstein was pursuing a dream far The Quest to Explain All Reality more ambitious than the theory of relativity. -

Origins: VI 12 December 2016 Page 1 Table of Contents

Origins: VI 12 December 2016 Page 1 Table of Contents You belong to the Universe Big History: Jonathon Keats ........... 3 Humanity’s Place in the Cosmos Olga García Moreno .......... 25 Big History at Broome Senior New Big History Site in Spanish ....................................................................... 26 High School in Australia Hayden Brown ........... 5 IBHA Members ................................................................................................... 27 New Big History MOOC .................................................................................... 28 First Prize to Dr. Javier Collado Ruano from La Fundación Columbia ..................... 24 Origins Editor: Lowell Gustafson, Villanova University, Pennsylvania (USA) Origins. ISSN 2377-7729 Thank you for your Associate Editor: Cynthia Brown, Dominican University of California (USA) membership in Assistant Editor: Esther Quaedackers, University of Amsterdam (Netherlands) Please submit articles and other material to Origins, Editor, [email protected] the IBHA. Your membership dues Editorial Board Mojgan Behmand, Dominican University of California, San Rafael (USA) The views and opinions expressed in Origins are not necessarily those of the IBHA Board. all go towards the Craig Benjamin, Grand Valley State University, Michigan (USA) Origins reserves the right to accept, reject or edit any material submitted for publication. adminsitration of David Christian, Macquarie University, Sydney (Australia) the association, but do not by Andrey Korotayev, Moscow -

Tom Hanks Takes Imax to the Moon Hacking Online Poker

TOM HANKS TAKES IMAX TO THE MOON HACKING ONLINE POKER All you-can-eat of tomorrow with your host Jon Stewart Why YAHOO! will be The Dream Factory the center of the How to turn your million-channel universe desktop into a custom “Fab Lab” ESPN thinks oustide the box The Wired Blood Feud Guide to TV 2.0 Greed, Denial, and DNA in Indian Country LOOK! UP IN THE SKY! The science of superheroes page 60 Watch it, buddy September 2005 September 2005 www.wired.com/wired 134 128 56 102 55 77 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 102 The TV of Tomorrow 25 RANTS & RAVES: Feedback. He’s the smart-ass host of the Daily Show. But more than that, Jon Stewart is helping to invent a new kind 29 START: Technology. Business, People. of TV- time-shifted and multiscreen. by Thomas Goetz PLUS: TV 2.0! Six new ways to watch, from the 32 Scofflaw: ‘80s classics on your PSP internet to celevision. 38 What I did at geek summer camp 106 The Super Network With video search and holywood muscle, Yahoo! 42 B.F.D.: Self Healing microchips! hopes to dominate the million-channel universe.by Josh McHugh 44 The do-it-yourself space program 112 ESPN Thinks Outside the Box 46 Infoporn Raw data. Web, WiMax, cell phones, and more. The sports Tracking the censors: The nations the block Web sites powerhouse is about to be on every screen in your and what really offends them. PLUS. Jargon Watch, life. by Frank Rose Wired Tired Expired, and more.. -

The Historical Emergence and Conceptual Context of Neuro-Art

Art and Neuroscience: The Historical Emergence and Conceptual Context of Neuro-Art by Carin Laura D’Souza A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Approved Dissertation Committee: Prof. Dr. Paul Crowther, chair Prof. Dr. Claus Hilgetag Dr. Timothy Senior Prof. Dr. Robert Zwijnenberg Date of Defense: November 13, 2012 School of Humanities and Social Science, Jacobs University, Bremen i ii Abstract This study has developed on the premise that neuroscience has a significant impact on contemporary art, and on the observation that, from the dialogue with neuroscience, a new artistic tendency has been emerging. The aim of this research was therefore to investigate the roots, the emergence, and development of what I generically call neuro art. The main objective of the research was to initiate the history of neuro art. This history of neuro art investigates, for the first time, the relationship between neuroscience and contemporary practice of the visual arts by identifying and examining those artworks that rely on knowledge of the brain and the nervous system. The study begins with a broad analysis of the role neuroscience plays in contemporary culture. The analysis situates neuro art within the larger context of cultural interactions with neuroscience, defines neuro art, and frames the history of neuro art in relation with two other disciplines: neuroaesthetics and neuroarthistory. The core of the research addresses in detail the history of art objects about the brain and the nervous system. Setting the scene, the thesis first describes the earlier manifestations of neuro art and identifies its conceptual and historical roots. -

Doubting Conventional Reality: Visual Art and Quantum Mechanics Lynden Elizabeth Stone BA LLM BFA (Hons) Queensland College Of

Doubting Conventional Reality: Visual Art and Quantum Mechanics Lynden Elizabeth Stone BA LLM BFA (Hons) Queensland College of Art Arts Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 2 Synopsis Quantum mechanics give significant cause to doubt conventional reality. This exegesis answers the question of how visual art, in engaging with quantum concepts, can enable a viewer to doubt conventional reality. I argue that visual art can do this by an artwork’s capacity to provoke unconventional thinking in the viewer and by the artist’s prudent considerations of materials and metaphor. I discuss my own artworks and those of others to assess the capacity of such works to cause ruptures of expected reality and so enable a viewer to doubt conventional reality. In particular, I argue that my three ‘mind works’ projects (the Metaphase Typewriter revival project, the Mind Lamp project and the Mind dispenser) are successful (even just on a metaphoric level) in enabling a viewer to doubt conventional reality. Specifically, this is because they provide the viewer opportunities to interact with events of quantum superposition, using only consciousness, to arguably affect or even create material reality. 3 4 Statement of Originality This work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is