Napier 85-108

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focusing Attention T O P I

43-2410 - Module 7: Introduction Page 1 of 14 43-2410 - Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack MODULE 07: (Film) Music, Meaning, Emotion, Communication INTRODUCTION t o p i c s Focusing attention - Accents Cognitive aspects of pitch and time in music -Melody - Contours - Tonality Memory limits - Data reduction - Categories Complexity, Prediction, Preference, Interest Maximal variety with minimal elements - Musical scales as psychological constructs Focusing Attention Experiencing time Our experience of time seems to often proceed independently from clock time. Musical organization of sounds may offer us means to explore this difference. The fleeting nature of non-linguistic sound events (in music, film, etc), accentuated by the potential absence of a referent, highlights the larger problem of defining the perceptual 'present.' Present is shaped by our selective attention to events or aspects of events. This selective attention and, therefore, our experience of 'present' events is always mediated by the memory of past events and the expectation of future ones, while at the same time reshaping both our memories and our expectations. The dialectic nature of the way we experience the present, past, and future is defining of the human experience of time and is explored within phenomenological research (e.g. Ricoeur, 1991; "Time and Narrative"). 43-2410 - Module 7: Introduction Page 2 of 14 Two competing theories of time within psychology I_ Storage-size theory (Ornstein, 1969). Memory storage-needs influence our estimates of time: a percept containing a large amount of information will require more storage capacity in short-term memory, generating the impression of greater elapsed time. II_ Attentional capacity theories (Hicks et al., 1976; Block, 1978; etc.). -

A Qualitative Exploration of the Internalised Use of Aural, Visual, Kinaesthetic, and Other Imagery in the Perception and Performance of Music

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year In search of the inner voice: a qualitative exploration of the internalised use of aural, visual, kinaesthetic, and other imagery in the perception and performance of music Nicole Saintilan University of Wollongong Saintilan, Nicole, In search of the inner voice: a qualitative exploration of the inter- nalised use of aural, visual, kinaesthetic, and other imagery in the perception and performance of music, PhD thesis, Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/725 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/725 In Search of the Inner Voice: A Qualitative Exploration of the Internalised use of Aural, Visual, Kinaesthetic, and Other Imagery in the Perception and Performance of Music Completed in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Nicole Saintilan BCA (Hons), M Mus, A Mus A, Grad Dip Ed Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong 2008 Statement of Sources Apart from the acknowledged borrowings from other sources, the work in this thesis, to my knowledge, is original. No part of this thesis has been submitted to any other institution for academic credit. Nicole Saintilan. September, 2008 ii Style Guidelines According to Departmental advice received, the Style Guidelines to be adopted for the presentation of this thesis were optional. Therefore, the guidelines of choice were those of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Society (5th.ed.). Taken into account was the variation allowed by these guidelines (for material other than journal articles) that is not only permissible, but also desirable in the interests of clear communication. -

Chapter 6 SOME NEWLY CREATED MISHRA RAGA

Chapter 6 SOME NEWLY CREATED MISHRA RAGA SOME NEW CREATIONS : Raga Jogkauns : (A landmark of modem mishra raga) This is an excellent creation of late Pt. Jagannath Buva Purohit "Gunidas". It is a combination of Raga Jog, Chandrakauns (both old and newly created by Prof. Devdhar). Chalan: tit Pi <4 - ST Pt Wf, FlI'PI’ll m n *r n n P( \ w n *t \st, v 3tj\stv X{ *f nji # \*tst^*ftPtsi^sft srPr tft *r *t, v i\5 *nt h *t, *rr Here, (1) Phrase *tT *1 *1*1 is used for raga Jog (2) Phrase *tT *1 *1 *IJHT is also used for raga Jog (3) Phrase tfT Pt «(P[ tn is used for raga Chandrakaus (4) Phrase 4 tfT is also used for raga Chandrakaus (5) Phrase *1 *t ^ ’s also used for raga Chandrakaus (6) Phrase 4 st Pi^st 4 is used for od Chandrakaus While discussing this raga with Prof. N.V.Patwardhan on 18/12/88 he told us that he had a wide discussion with Buva and Buva has told him that while creating the raga Jogkaus the old Chandrakaus having komal Nishad was in his mind. So he had used phrase 4 % 4... which now an identical phrase of raga Jogkaus ( *t tt 4t^t 4 4^44 ) Also discussing this raga with Pt. Arvind Parikh a sitar mastreo and disciple of Sh. Ustad VilayatKhan; he also told that he believes only one newly created mishra raga which may be called as a land mark of mishra raga is only raga Jogkaus created by Pt. -

Shepard, 1982

Psychological Review VOLUME 89 NUMBER 4 JULY 1 9 8 2 Geometrical Approximations to the Structure of Musical Pitch Roger N. Shepard Stanford University ' Rectilinear scales of pitch can account for the similarity of tones close together in frequency but not for the heightened relations at special intervals, such as the octave or perfect fifth, that arise when the tones are interpreted musically. In- creasingly adequate a c c o u n t s of musical pitch are provided by increasingly gen- eralized, geometrically regular helical structures: a simple helix, a double helix, and a double helix wound around a torus in four dimensions or around a higher order helical cylinder in five dimensions. A two-dimensional "melodic map" o f these double-helical structures provides for optimally compact representations of musical scales and melodies. A two-dimensional "harmonic map," obtained by an affine transformation of the melodic map, provides for optimally compact representations of chords and harmonic relations; moreover, it is isomorphic to the toroidal structure that Krumhansl and Kessler (1982) show to represent the • psychological relations among musical keys. A piece of music, just as any other acous- the musical experience. Because the ear is tic stimulus, can be physically described in responsive to frequencies up to 20 kHz or terms of two time-varying pressure waves, more, at a sampling rate of two pressure one incident at each ear. This level of anal- values per cycle per ear, the physical spec- ysis has, however, little correspondence to ification of a half-hour symphony requires well in excess of a hundred million numbers. -

108 Melodies

SRI SRI HARINAM SANKIRTAN - l08 MELODIES - INDEX CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1-2 Samant Sarang 37 Indian Classical Music Theory 3-13 Kurubh 38 Harinam Phylosphy & Development 14-15 Devagiri 39 FIRST PRAHAR RAGAS (6 A.M. to 9 A.M.) THIRD PRAHAR RAGAS (12 P.M. to 3 P.M.) Vairav 16 Gor Sarang 40 Bengal Valrav 17 Bhimpalasi 4 1 Ramkal~ 18 Piloo 42 B~bhas 19 Multani 43 Jog~a 20 Dhani 44 Tori 21 Triveni 45 Jaidev 22 Palasi 46 Morning Keertan 23 Hanskinkini 47 Prabhat Bhairav 24 FOURTH PKAHAR RAGAS (3 P.M. to 6 P.M.) Gunkali 25 Kalmgara 26 Traditional Keertan of Bengal 48-49 Dhanasari 50 SECOND PRAHAR RAGAS (9 A.M. to 12 P.M.) Manohar 5 1 Deva Gandhar 27 Ragasri 52 Bha~ravi 28 Puravi 53 M~shraBhairav~ 29 Malsri 54 Asavar~ 30 Malvi 55 JonPurl 3 1 Sr~tank 56 Durga (Bilawal That) 32 Hans Narayani 57 Gandhari 33 FIFTH PRAHAR RAGAS (6 P.M. to 9 P.M.) Mwa Bilawal 34 Bilawal 35 Yaman 58 Brindawani Sarang 36 Yaman Kalyan 59 Hem Kalyan 60 Purw Kalyan 61 Hindol Bahar 94 Bhupah 62 Arana Bahar 95 Pur~a 63 Kedar 64 SEVENTH PRAHAR RAGAS (12 A.M. to 3 A.M.) Jaldhar Kedar 65 Malgunj~ 96 Marwa 66 Darbar~Kanra 97 Chhaya 67 Basant Bahar 98 Khamaj 68 Deepak 99 Narayani 69 Basant 100 Durga (Khamaj Thhat) 70 Gaur~ 101 T~lakKarnod 71 Ch~traGaur~ 102 H~ndol 72 Shivaranjini 103 M~sraKhamaj 73 Ja~tsr~ 104 Nata 74 Dhawalsr~ 105 Ham~r 75 Paraj 106 Mall Gaura 107 SIXTH PRAHAR RAGAS (9Y.M. -

The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’S

1 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’s Francesca Mary Greatorex Theatre and Performance Department Goldsmiths University of London A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: ……………………………………………. 3 Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been written without the generosity of many individuals who were kind enough to share their knowledge and theatre experience with me. I have spoken with actors, musical directors, set designers, directors, singers, choreographers and actor-musicians and their names and testaments exist within the thesis. I should like to thank Emily Parsons the archivist for the Liverpool Everyman for all her help with my endless requests. I also want to thank Jonathan Petherbridge at the London Bubble for making the archive available to me. A further thank you to Rosamond Castle for all her help. On a sadder note a posthumous thank you to the director Robert Hamlin. He responded to my email request for the information with warmth, humour and above all, great enthusiasm for the project. Also a posthumous thank you to the actor, Robert Demeger who was so very generous with the information regarding the production of Ninagawa’s Hamlet in which he played Polonius. Finally, a big thank you to John Ginman for all his help, patience and advice. 4 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors During the Period 1960 to 2000. -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICD Section) Indian Cultural Programmes 2012 April-March 2013 S.No. Name of the Programme

Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICD Section) Indian Cultural Programmes 2012 April-March 2013 S.No. Name of the Programmes Style Date of Performance 1. Ms. Sonam Kalra Sufi Singer 12th April, 2012 2. Ms. Swaswati Sen Kathak 12th April, 2012 3. Dr. Ileana Citaristi Odissi (H) 13th April, 2012 4. Ms. Nibedita Mohapatra Odissi (Lec-dem) 17th April, 2012 5. Mr. Manish Sharma Jal Tarang (H) 20th April, 2012 6. Mr. Ustad Mazhar Ali Vocal 21st April, 2012 Khan,Ustad Jawaad Ali Khan & Hans Raj Hans 7. Matrix Creative group Bollywood Dhamaka 23rd April, 2012 8. Mr. Rajat Kapoor Theater 26th April, 2012 9. Ms. Aruna Vasude Buddist (H) 27th April, 2012 10. Ms. Pragati Sood Kathak Lec-dem 2nd May, 2012 11. Mr. Sudip Kr. Flute recital (H) 4th May, 2012 Chattopadayay, Kolkata 12. Ms. Sangeeta Sharma Theatre (H) 11th May, 2012 13. Ms. Kavita Divedi Lec dem 13th May, 2012 14. Ms. Sohaila Kapur Dance Theatre (H) 18th May, 2012 15. Ms. Anjana Jha Kathak (H) 25th May, 2012 16. Ms. Ashvari Majumdar Kathak (Lec. Dem) 30th May, 2012 17. Prof. Lovely Sharma Sitar Recital (H) Agra 1st June, 2012 18. Mr. Anil Bhatt Puppet Show (H) 8th June, 2012 19. Mrs. Rina Jana Odissi Dance (H) 15th June, 2012 Kolkata 20. Mr. Neel Ranjan Mukherjee Hawaiian Guitar (H) 22nd June, 2012 21. Dr. Janaki Rangarajan Bharatanatyam (H) 29th June, 2012 Chennai 22. Mr. Shekhar Sen from “Kabeer” Play 2nd July, 2012 Mumbai 23. Malhaar Festival-2012 1. Meeta Pandit Hindustani Vocal 8th July, 2012 2. Rama Vaidyanathan Bharatanatyam 8th July, 2012 3. -

Sept17 Cal Box.Cdr

Dear Member, September arrives with tremendous promise marked by standalone Quality Street Sat Bhashe Raidas initiatives designed to transform your urban experience! (English/60mins) (Hindi/95mins) Habitat Film Club Notably, IHC, in collaboration with the Ministry of Youth Affairs & Dir. Rasika Agashe Presents A solo directed & performed Sports, begins the Khelo India Series, a quarterly lecture series Writ. Rajesh Kumar A Festival of Iranian Cinema featuring sports icons who will discuss their vision and share life by Maya Krishna Rao Prod. Being Association Collab. Iran Culture House, New Delhi based on a short story by experiences. A platform that aims to nurture sports culture in the 3 Sept 7:00pm|Bodyguard (Persian/2016/95mins) Dir. Ebrahim country and generate valuable insights on sports policy, infrastructure Chimamanda Adichie Hatamikia and opportunities, the maiden lecture on 4 Sept will be delivered by 4 Sept 7:00pm | Sweet Taste of Imagination (Persian/2014/90mins) 22 Sept | 7:00pm Pullela Gopichand, Chief National Coach of the Indian Badminton 9 Sept | 7:30pm Dir. Kamal Tabrezi The Amphitheatre, IHC Team. It is only apt that his lecture falls on the eve of Teacher's Day The Stein Auditorium 5 Sept 7:00pm | Crazy Castle (Persian/2015/115mins) Dir. Abdolhasan Davoodi celebrated across the country in honour of the enduring interventions of For 10 years & above the teaching community. Tickets at Rs.500, Rs.350 & Rs.200 11 Sept 7:00pm | Where are My Shoes (Persian/2016/90mins) Tickets at Rs.300 from 1 Sept. for IHC members Dir. Kioumars Pourahmad available at the Programmes Desk IHC will collaborate with Research and Information System for & open to all from 4 Sept. -

INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE Volume XXVIII

diary Price Re.1/- INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE volume XXVIII. No. 2 March – April 2014 composed Carnatic music in Hindustani ragas as well as Same Difference NottuSvarams inspired by British band music; in recent MUSIC APPRECIATION PROMOTION: The North–South years, Carnatic ragas such as Hamsadhwani and Convergence in Carnatic and Hindustani Music Charukeshi have been adopted enthusiastically by the Panelists: Subhadra Desai, Saraswati Rajagopalan north; Maharashtrian abhangs have become staples at and Suanshu Khurana Chair: Vidya Shah, March 21 Carnatic concerts; Indian classical music has shown a PERFORMANCE: A Celebration of Carnatic and willingness to naturalise Western imports such as the Hindustani Music violin, guitar, saxophone, mandolin and even the organ. Carnatic Vocal Recital by Sudha Raghunathan So what this really means is that you have two distinct Hindustani Vocal Recital by Meeta Pandit systems, with often disparate ideas about what constitutes Collaboration: Spirit of India, March 22 good music production, but tantalisingly similar lexicons and grammatical constructs that occasionally become the This was a thought-provoking discussion-demonstration basis for some interesting conversations. on the convergence between Carnatic and Hindustani music, two systems divided by a putatively common These insights kept coming to mind the next evening, musical language. The audience certainly converged; as to when the clamour of birdsong at the picturesque Rose the systems, it was largely a revelation of their divergences, Garden heralded performances by Meeta Pandit of the though a very interesting, and at times even amusing one. Gwalior gharana and then Sudha Raghunathan, the Madras Music Academy’s Sangeeta Kalanidhi for this Carnatic training begins with the raga Mayamalavagaula, year. -

For the Mande Bala Todd G. Martin A

TOWARD A PEDAGOGY OF "PLAY" FOR THE MANDE BALA TODD G. MARTIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL, 2017 © Todd Martin, 2017 ABSTRACT A theoretical model is proposed that posits "play" as both the long-term goal of bala learning, and as the means through which the short-term steps toward that goal can best be achieved. Play is defined in two different ways. In the first sense it is an orchestrating of means and ends in which means are at the centre of interest. In this sense, play is a goal of bala learning. In the second sense, play is defined (using the framework of Applied Behaviour Analysis) as: activities that (a) are inherently reinforcing (and not inherently punishing), and (b) do not eventuate extinction, escape, or avoidance. In this sense, play is conceived as one possible means through which to achieve pedagogical goals. The case is made that owing to its intrinsic (musical) characteristics—in particular, the inherent scalability of pattern density—Mande bala music is especially well suited to a pedagogy of "play." Although the model proposed is supported by empirical evidence and has a strong rational underpinning, the model itself is not tested in the present study, but rather, is herein articulated (via illustrative case studies depicting the learning of various bala patterns through digitally mediated means—books, CDs, DVDs, etc.) An argument is built to support the notion that in comparison with traditional, immersion- based pedagogical modalities, the digital mediation of bala teaching eventuates a pedagogical loss, but that this pedagogical loss can be attenuated through a more "playful" pedagogical approach. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’, Mumbai ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume - Annual: TRN 2007 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’, Mumbai ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume - Annual: TRN 2007 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Branches: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded, Tuljapur, Baroda, Amravati ============================================================= Feature Article in this Issue: Gramophone Celebrities-II Other articles : Teheran Records, O. P. Nayyar. 1 ‘The Record News’ – Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members --------------------------- V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US$ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full membership fee and get a copy -

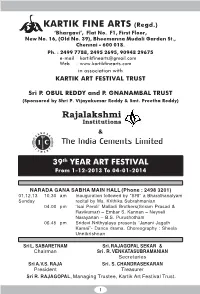

KARTIK FINE ARTS (Regd.) Rajalakshmi

DATE : 18-11-2012 KARTIK FINE ARTS (Regd.) ‘Bhargavi’, Flat No. F1, First Floor, New No. 16, (Old No. 39), Bheemanna Mudali Garden St., Chennai - 600 018. Ph. : 2499 7788, 2495 2695, 90948 29675 e-mail : [email protected] Web : www.kartikfinearts.com in association with KARTIK ART FESTIVAL TRUST Sri P. OBUL REDDY and P. GNANAMBAL TRUST (Sponsored by Shri P. Vijayakumar Reddy & Smt. Preetha Reddy) Rajalakshmi Institutions & 39th YEAR ART FESTIVAL From 1-12-2013 To 04-01-2014 NARADA GANA SABHA MAIN HALL (Phone : 2498 3201) 01.12.13 10.30 am Inauguration followed by "SRI" a Bharathanatyam Sunday recital by Ms. Krithika Subrahmanian 04.00 pm ‘Isai Peroli’ Malladi Brothers(Sriram Prasad & Ravikumar) – Embar S. Kannan – Neyveli Narayanan – B.S. Purushotham 06.45 pm Sridevi Nrithyalaya presents “Janani Jagath Karani”- Dance drama. Choreography : Sheela Unnikrishnan Sri L. SABARETNAM Sri. RAJAGOPAL SEKAR & Chairman Sri . R. VENKATASUBRAMANIAN Secretaries Sri A.V.S. RAJA Sri . S. CHANDRASEKARAN President Treasurer Sri R. RAJAGOPAL, Managing Trustee, Kartik Art Festival Trust. 1 DATE : 18-11-2012 NARADA GANA SABHA MINI HALL (Phone-24983201) 02.12.13 10.00 am Mandolin Sisters (Sreesha & Sreeusha) – Monday Delhi Sairam – B. Subba Rao 12.15 pm R. Rajiv – R. Rajesh – Ammangudi Ramanarayanan 02.00 pm Jayakrishnan – C.N. Srinivasamurthy – V.S. Raghavan NARADA GANA SABHA MAIN HALL (Phone- 24983201) 04.30 pm S. Saketha Raman – Nagai Sriram – Umayalpuram Dr. K. Sivaraman – Giridhar Udupa 06.45 pm Hindustani Classical Recital by renowned Vocalist from Delhi MEETA PANDIT NARADA GANA SABHA MINI HALL (Phone-24983201) 03.12.13 10.00 am N.