To Old English Metre (Version 1.5, September 26Th 2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Editor's Introduction

Editor’s Introduction: Scansion DAVID NOWELL SMITH _______________________ I would like to start from an intuition.1 This might seem an abuse of editorial privilege, and indeed might strike one as more generally tendentious: is an issue on ‘scansion’ the place for discussing one’s intuitions at all? For a start, it contravenes quite brazenly the strict separation between description and performance, lain down most powerfully by John Hollander well over half a century ago. For Hollander, a ‘descriptive’ system of scansion would aim at presenting schematically the whole ‘musical’ structure of a poem, whether this consists, in any particular case, of the prosodic features of the language in which it is written, the arrangement of elements completely foreign to that language (syllable counting in English verse for example), or even the arrangement of type on a page. A performative system of scansion, on the other hand, would present a series of rules governing a locutionary reading of a particular poem, before a real or implied audience. It would end up by describing not the poem itself, but the unstated canons of taste behind the rules. Performative systems of scansion, disguised as descriptive ones, have composed all but a few of the metrical studies of the past. Their subjectivity is far more treacherous than even that of reading poems into oscilloscopes and claiming that the image produced describes, or even is, the true poem.2 1 My great thanks to Ewan Jones on his comments on an earlier draft of this introduction. 2 John Hollander, ‘The Music of Poetry’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism vol. -

Introduction to Meter

Introduction to Meter A stress or accent is the greater amount of force given to one syllable than another. English is a language in which all syllables are stressed or unstressed, and traditional poetry in English has used stress patterns as a fundamental structuring device. Meter is simply the rhythmic pattern of stresses in verse. To scan a poem means to read it for meter, an operation whose noun form is scansion. This can be tricky, for although we register and reproduce stresses in our everyday language, we are usually not aware of what we’re going. Learning to scan means making a more or less unconscious operation conscious. There are four types of meter in English: iambic, trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic. Each is named for a basic foot (usually two or three syllables with one strong stress). Iambs are feet with an unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable. Only in nursery rhymes to do we tend to find totally regular meter, which has a singsong effect, Chidiock Tichborne’s poem being a notable exception. Here is a single line from Emily Dickinson that is totally regular iambic: _ / │ _ / │ _ / │ _ / My life had stood – a loaded Gun – This line serves to notify readers that the basic form of the poem will be iambic tetrameter, or four feet of iambs. The lines that follow are not so regular. Trochees are feet with a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. Trochaic meter is associated with chants and magic spells in English: / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Double, double, toil and trouble, / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Fire burn and cauldron bubble. -

Beowulf Themes

Wednesday, November 12, 2014 • Do now: In your notebooks, answer the following prompt: –What is a hero? Explain your definition and give examples. Thursday, November 13, 2014 • Do now: In your notebooks, answer the following prompt: –What is courage? How would most people today define courage? Beowulf Themes • Good vs Evil • Violence • Identity • Courage • Strength and • Mortality Skill • The • Wealth Supernatural • Religion • Traditions & Customs Beowulf Motifs/Symbols • Motifs • Symbols –Monsters –The Golden –The Oral Torque Tradition (Rewards) –The Mead –The Banquet Hall (Celebration) Beowulf Author • Very little is known about the author –Male –Educated –Upper Class –Anglo-Saxon / Christian Beowulf Information • Poem was composed (created) in the 8th century – Although it is English in language and origin, the poem does not deal with Englishmen, but their Germanic ancestors (Danes & Geats) – The Danes are from Denmark & the Geats are from modern day Sweden Beowulf Info (cont’d) • Some of the original poem was destroyed in the Ashburnham House Fire, causing a number of lines to be lost forever (1731) • The poem is circular in that it starts out with a young warrior, he grows old, another young warrior saves the day, etc. (comes full circle) Beowulf Info (cont’d) • Beowulf’s people are the Geats • Hrothgar’s people are the Danes • Beowulf reigned as king for 50 years • According to legend, Beowulf died at the age of 90 years old • Beowulf takes place in Scandinavia Beowulf’s Origin So why wasn’t it written down in the first place? This story was probably passed down orally for centuries before it was first written down. -

Understanding Poetry Are Combined to Unstressed Syllables in the Line of a Poem

Poetry Elements Sound Includes: ■ In poetry the sound Writers use many elements to create their and meaning of words ■ Rhythm-a pattern of stressed and poems. These elements include: Understanding Poetry are combined to unstressed syllables in the line of a poem. (4th Grade Taft) express feelings, ■ Sound ■ Rhyme-similarity of sounds at the end of thoughts, and ideas. ■ Imagery words. ■ The poet chooses ■ Figurative ■ Alliteration-repetition of consonant sounds at Adapted from: Mrs. Paula McMullen words carefully (Word the beginning of words. Example-Sally sells Language Library Teacher Choice). sea shells Norwood Public Schools ■ Poetry is usually ■ Form ■ Onomatopoeia- uses words that sound like written in lines (not ■ Speaker their meaning. Example- Bang, shattered sentences). 2 3 4 Rhythm Example Rhythm Example Sound Rhythm The Pickety Fence by David McCord Where Are You Now? ■ Rhythm is the flow of the The pickety fence Writers love to use interesting sounds in beat in a poem. The pickety fence When the night begins to fall Give it a lick it's their poems. After all, poems are meant to ■ Gives poetry a musical And the sky begins to glow The pickety fence You look up and see the tall be heard. These sound devices include: feel. Give it a lick it's City of lights begin to grow – ■ Can be fast or slow, A clickety fence In rows and little golden squares Give it a lick it's a lickety fence depending on mood and The lights come out. First here, then there ■ Give it a lick Rhyme subject of poem. -

ASSESSING POETRY MARKUP with NUSCHOLAR by MEGHA JYOTI

ASSESSING POETRY MARKUP WITH NUSCHOLAR by MEGHA JYOTI Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Computer Science at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia December 2013 © Copyright by Megha Jyoti, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................... viii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... ix ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... xi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... xii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Benefits of Digital Scansion Tool ............................................................................... 3 1.2 Motivation ................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Thesis Contribution ................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Solution Overview ..................................................................................................... 6 1.4.1 Requirement Gathering ................................................................................. 6 1.4.2 Design and Implementation ......................................................................... -

1 Social and Linguistic Setting of Alliterative Verse in Anglo-Saxon and Medieval England

Cambridge University Press 0521573173 - Alliteration and Sound Change in Early English - Donka Minkova Excerpt More information 1 Social and linguistic setting of alliterative verse in Anglo-Saxon and Medieval England The primary goal of this study is to establish and analyze the linguistic prop- erties of early English verse. Verse is not created in a vacuum; a consideration of some non-structural factors that could influence the composition of poetry is important for our understanding of its linguistic dimensions. This chapter presents a brief overview of the social and cultural conditions under which alliterative verse was produced and enjoyed in Anglo-Saxon and Medieval England. 1.1 The Anglo-Saxon poetic scene Verse composition was a foremost outlet of creativity and a cherished form of entertainment, moral edification, and historical record keeping for the Anglo- Saxons. When the Northumbrian priest and chronicler Bede (b. 672/673– d. 735) wrote his Ecclesiastical History of the English People in Latin, the poetic rendition of important themes and events in the vernacular must have already been a highly prestigious undertaking. Bede tells us how Cadmon, an illiterate shepherd, found his inability to sing in company shameful. In a dream a stranger appeared urging him to sing the song of the Creation and he uttered “verses which he had never heard.” He was then taken to the monastery at Whitby where his divine poetic gift was tested and confirmed. He spent the rest of his life as a layman in the monastery, enjoying the fellowship of the abbess and the learned brethren, and composing more religious poetry. -

A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 4-16-1983 A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur Jay Curlin Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Curlin, Jay, "A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur" (1983). Honors Theses. 209. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CLOSE LOOK AT TWO POEMS BY RICHARD WILBUR Jay Curlin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Honors Program Ouachita Baptist University The Department of English Independent Study Project Dr. John Wink Dr. Susan Wink Dr. Herman Sandford 16 April 1983 INTRODUCTION For the past three semesters, I have had the pleasure of studying the techniques of prosody under the tutelage of Dr. John Wink. In this study, I have read a large amount of poetry and have studied several books on prosody, the most influential of which was Poetic Meter and Poetic Form by Paul Fussell. This splendid book increased vastly my knowledge of poetry. and through it and other books, I became a much more sensitive, intelligent reader of poems. The problem with my study came when I tried to decide how to in corporate what I had learned into a scholarly paper, for it seemed that any attempt.to do so would result in the mere parroting of the words of Paul Fussell and others. -

Eomer Gets Poetic: Tolkien's Alliterative Versecraft James Shelton East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 6 2018 Eomer Gets Poetic: Tolkien's Alliterative Versecraft James Shelton East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Shelton, James (2018) "Eomer Gets Poetic: Tolkien's Alliterative Versecraft," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol5/iss1/6 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Shelton: Eomer Gets Poetic: Tolkien's Alliterative Versecraft The fact that Tolkien had an affinity for Old English and, therefore, Old English impacted his writing style are two contentions which are variously argued and proven throughout Tolkien scholarship. They are well supported enough that they need not be rehashed here, see Shippey, Flieger, Higgins, et passim. It is enough for this investigation into Tolkien's use of Old English alliterative verse to note his penchant for leaning heavily on such forms as he enjoyed, and had a professional interest in, is widely accepted in Tolkien scholarship. Additionally, it should be mentioned that Tolkien's use of Old English seems to be at its peak with the Riders of Rohan. In fact, to paraphrase Michael Drout, the Riders of Rohan are Anglo-Saxons except they have horses.1 Additionally, it has been stipulated that the Riders of Rohan use a specific dialect of Old English known as Mercian. -

The Walrus and the Carpenter

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y A RT I C L E The Walrus and the Carpenter National Geographic photographs illustrate Lewis Carroll's "The Walrus and the Carpenter," and instructional material provides a guide through the poem's literary devices. G R A D E S 7 - 12+ S U B J E C T S English Language Arts C O N T E N T S 1 Interactive For the complete geostories with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/walrus-carpenter-natgeo/ "The Walrus and the Carpenter," a silly and surprisingly morbid poem by Lewis Carroll, was published in 1865. It was a part of the book Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There, a sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. The poem is a narrative, or story, told by the annoying twins Tweedledum and Tweedledee. The GeoStory "The Walrus and the Carpenter . And National Geographic", above, provides the entire text of the poem. It also includes a walk through the poem, with an image and map accompanying each stanza, and in many cases individual lines. The images are either literal representations or metaphors of a line in the stanza. Use the GeoStory to better understand metaphors and other literary devices. Metaphors are figures of speech or visual representations in which a term is applied to something it could not possibly be. "Students have an appetite for learning," for example, is a metaphor. Students don't actually have an appetite for anything except food! Carroll uses a number of other literary devices in "The Walrus and the Carpenter." A series of possible discussion questions about the literary devices used in the poem is provided in the following tab, "Questions." The discussion topics progress from the simplest to the most difficult. -

Audible Punctuation Performative Pause In

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/140838 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-25 and may be subject to change. AUDIBLE PUNCTUATION Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. Th.L.M. Engelen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 21 mei 2015 om 14.30 uur precies door Ronald Blankenborg geboren op 23 maart 1971 te Eibergen Promotoren: Prof. dr. A.P.M.H. Lardinois Prof. dr. J.B. Lidov (City University New York, Verenigde Staten) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. M.G.M. van der Poel Prof. dr. E.J. Bakker (Yale University, Verenigde Staten) Prof. dr. M. Janse (Universiteit Gent, België) Copyright©Ronald Blankenborg 2015 ISBN 978-90-823119-1-4 [email protected] [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Printed by Maarse Printing Cover by Gijs de Reus Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Doctoral Thesis to obtain the degree of doctor from Radboud University Nijmegen on the authority of the Rector Magnificus prof. -

Dactylic Hexameter Is Properly Scanned When Divided Into Six Feet, with Each Foot Labelled a Dactyl Or a Spondee

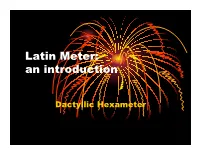

Latin Meter: an introduction Dactyllic Hexameter English Poetry: Poe’s “The Raven”—Trochaic Octameter / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / x Once up- on a mid- night drear- y, while I pon- dered weak and wear- y / x / x x / x / x x / x / x / x / O- ver man- y a quaint and cur- i- ous vol- ume of for- got- ten lore, / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / x While I nod- ded, near- ly nap- ping, sud- den- ly there came a tap- ping, / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / As of some- one gent- ly rap- ping, rap- ping at my cham- ber door. / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / “’Tis some vis- i- tor,” I mut- tered, “tap- ping at my cham- ber door; / x / x / x / On- ly this, and noth- ing more.” Scansion n Scansion: from the Latin scandere, “to move upward by steps.” Scansion is the science of scanning, of dividing a line of poetry into its constituent parts. n To scan a line of poetry is to follow the rules of scansion by dividing the line into the appropriate number of feet, and indicating the quantity of the syllables within each foot. n A line of dactylic hexameter is properly scanned when divided into six feet, with each foot labelled a dactyl or a spondee. Metrical Symbols: long: – short: u syllaba anceps: u (may be long or short) Basic Feet: dactyl: – u u spondee: – – Dactylic Hexameter: Each line has six feet, of which the first five may be either dactyls or spondees, though the fifth is nearly always a dactyl (– u u), and the sixth must be either a spondee (– –) or a trochee (– u), but we will treat it as a spondee. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg.