STS/EACTS Short List Mapping to European Paediatric Cardiac Code Short List with ICD-9 & ICD-10 Crossmapping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

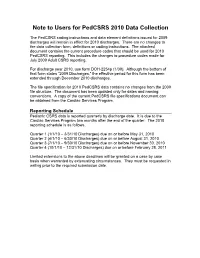

Note to Users for Pedcsrs 2010 Data Collection

Note to Users for PedCSRS 2010 Data Collection The PedCSRS coding instructions and data element definitions issued for 2009 discharges will remain in effect for 2010 discharges. There are no changes to the data collection form, definitions or coding instructions. The attached document contains the current procedure codes that should be used for 2010 PedCSRS reporting. This includes the changes to procedure codes made for July 2009 Adult CSRS reporting. For discharge year 2010, use form DOH-2254p (1/09). Although the bottom of that form states “2009 Discharges,” the effective period for this form has been extended through December 2010 discharges. The file specification for 2010 PedCSRS data contains no changes from the 2009 file structure. The document has been updated only for dates and naming conventions. A copy of the current PedCSRS file specifications document can be obtained from the Cardiac Services Program. Reporting Schedule Pediatric CSRS data is reported quarterly by discharge date. It is due to the Cardiac Services Program two months after the end of the quarter. The 2010 reporting schedule is as follows. Quarter 1 (1/1/10 – 3/31/10 Discharges) due on or before May 31, 2010 Quarter 2 (4/1/10 – 6/30/10 Discharges) due on or before August 31, 2010 Quarter 3 (7/1/10 – 9/30/10 Discharges) due on or before November 30, 2010 Quarter 4 (10/1/10 – 12/31/10 Discharges) due on or before February 28, 2011 Limited extensions to the above deadlines will be granted on a case by case basis when warranted by extenuating circumstances. -

Mustard Procedure Br Heart J: First Published As 10.1136/Hrt.72.1.85 on 1 July 1994

Br Heart J 1994;72:85-88 85 Transcatheter stent implantation for recurrent pulmonary venous pathway obstruction after the Mustard procedure Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.72.1.85 on 1 July 1994. Downloaded from Martin C K Hosking, Kenneth A Murdison, Walter J Duncan Abstract pathway obstruction reaching a maximum A 5 year old boy presented with obstruc- flow velocity of 2'0 m/s associated with a tion of the pulmonary venous pathway stenosis measuring 2-3 mm in diameter. four years after the Mustard procedure. Right ventricular dysfunction was a persistent A successful balloon dilatation ofthe pul- echocardiographic finding associated with an monary venous pathway was performed increase in left ventricle dimension in but the benefit was transient. Placement response to the rise of pulmonary arterial of a 10 mm balloon expandable intravas- pressure secondary to the pulmonary venous cular stent across the recurrent stenosis inflow obstruction. A significant systemic to resulted in complete relief ofthe obstruc- pulmonary venous chamber baffle leak mea- tion with prompt resolution ofthe clinical suring 5 mm x 4 mm with right to left shunting signs. The delivery system was modified was seen by Doppler colour flow mapping and to facilitate stent delivery. contributed to central cyanosis. Serial chest x ray films showed persistence of cardiomegaly (Br Heart 1994;72:85-88) with increasing evidence of pulmonary venous congestion. To avoid the risks of surgical repair in a Paediatric experience with transcatheter patient with impaired -

Mustard Operation

Mustard Operation William G. Williams The natural history of infants with complete transposi- desaturation. Mustard reasoned that both vena cavae tion (TGA) is rapid deterioration and death within the could be deliberately diverted to the left atrium while first few months of life. The few babies who do survive allowing the pulmonary return to enter the right atrium, beyond the first year of life usually have an associated thereby correcting the circulation in patients with TGA. ventricular septal defect (VSD) and subsequently dete- The Mustard baffle operation was a simple, reproduc- riorate with progressive pulmonary vascular disease. ible, and elegant technique of transposing venous re- Intervention to improve the outlook for newborns turn. It was easier to learn than the Senning operation, with TGA began with surgical resection of the atrial and became the standard repair in most of the world. septum.' The enlarged atrial defect improves mixing of the pulmonary and systemic circulations, thereby in- creasing the systemic oxygen saturation. Balloon atrial Indications for the Mustard Operation in 1998 septostomy, as described by Rashkind and Miller in The atrial repair of TGA has been almost entirely 1966,2 replaced surgical septectomy. The balloon cath- replaced by the arterial switch operation. However, eter technique continues to provide effective emergency there are three situations were the Mustard operation palliation for the newborn with TGA. may be indicated: In the early 1950s, a number of surgeons, including 1. For infants with isolated TGA who first present M~stard,~attempted arterial repair of TGA in infants, after the neonatal period, the Mustard operation is an all without success until Jatene's report in 1978.4 In alternative to the two-stage arterial switch operation, 1954, Albert5 proposed a surgical technique to trans- ie, a preliminary pulmonary artery banding to prepare pose the venous inflow within the atria to correct TGA. -

Relation of Biventricular Function Quantified by Stress

Relation of Biventricular Function Quantified by Stress Echocardiography to Cardiopulmonary Exercise Capacity in Adults With Mustard (Atrial Switch) Procedure for Transposition of the Great Arteries Wei Li, Tim S. Hornung, Darrel P. Francis, Christine O’Sullivan, Alison Duncan, Michael Gatzoulis and Michael Henein Circulation 2004;110;1380-1386; originally published online Aug 23, 2004; DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141370.18560.D1 Circulation is published by the American Heart Association. 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 72514 Copyright © 2005 American Heart Association. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0009-7322. Online ISSN: 1524-4539 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/110/11/1380 Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Circulation is online at http://circ.ahajournals.org/subsriptions/ Permissions: Permissions & Rights Desk, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 351 West Camden Street, Baltimore, MD 21202-2436. Phone 410-5280-4050. Fax: 410-528-8550. Email: [email protected] Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at http://www.lww.com/static/html/reprints.html Downloaded from circ.ahajournals.org at NHLI - Royal Brompton on January 29, 2006 Relation of Biventricular Function Quantified by Stress Echocardiography to Cardiopulmonary Exercise Capacity in Adults With Mustard (Atrial Switch) Procedure for Transposition of the Great Arteries Wei Li, MD, PhD; Tim S. Hornung, MD; Darrel P. Francis, MRCP; Christine O’Sullivan, BSc; Alison Duncan, MRCP; Michael Gatzoulis, MD, PhD; Michael Henein, MD, PhD Background—Mustard repair for transposition of the great arteries (TGA) is frequently associated with impaired systemic (right) ventricular function and sometimes exercise intolerance. -

Cardiac Surgery in Early Infancy J

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.48.562.478 on 1 August 1972. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (August 1972) 48, 478-485. Cardiac surgery in early infancy J. STARK M.D. Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, W.C. 1 IMPORTANT advances have been made in the diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart disease (CHD) in early infancy. Accurate diagnosis is now possible in the first days or even hours of life. Operation is also 3530- possible at this early age and very often it provides 0 the only chance for survival. The risk of conservative E .4In15 treatment often exceeds the risk of the operation. O- An aggressive approach to the diagnosis and treat- II II II ment of CHD is dictated by statistics. The estimated z a 10 5 incidence of CHD is 6-8/1000 live births. About 500o 963 99 6 of the children born with CHD die before their first 3 1 1 5 1 16 birthday unless effectively treated. The achievements in the treatment of CHD in infancy are the result of 1963~51964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 the combined efforts of paediatricians, cardiologists, FIG. 1. Open-heart surgery under I year of age at the copyright. surgeons, anaesthetists and nurses. Many other Great Ormond Street Thoracic Unit, February 1963 to specialists and technical staff contribute to the September 1971 (115 patients). Open columns, survived; diagnosis and treatment. closed columns, died. The experience of the Thoracic Unit, Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street, forms the Diagnosis basis of this report (unless otherwise stated). -

BAS Talk Linz

Balloon atrial septostomy Dr Aphrodite Tzifa, MD(Res), FRCPCH! ! Director, Paediatric Cardiology Department, ! Mitera Children's Hospital, Athens, Greece September 10, 2003 ! BAS ! ! 1. The technique of atrial septostomy (BAS) was introduced in 1966 by Rashkind! ! 2. The interventional procedure is performed in neonates that are significantly cyanosed with preductal O2 saturations below 75% after birth or that need an atrial septal defect to offload the LA! “A technique for producing an atrial septal defect without thoracotomy or anesthesia is presented. It can be performed rapidly in any cardiac catheterization laboratory.” (William J. Rashkind, 1966) ! History ! ! “...The initial response to this report varied between admiration and horror but, in either case, the procedure stirred the imagination of the “invasive” cardiologists throughout the entire cardiology world and set the stage for all future intracardiac interventional procedures – the true beginning of pediatric and adult interventional cardiology.” (Charles E. Mullins, 1998) ! HOW to CREATE AN ASD? ! ! 1. Septostomy Balloons! 2. Low profile balloon (Tyshak)! 3. Static balloon (Powerflex, Opta)! 4. Cutting balloons! 5. Blade septostomy catheter! 6. Stenting! ! Transeptal puncture or RF perforation may occasionally be needed Need for creation or enlargement of an ASD: ! WHEN? ! ! 1. TGA: In some units, an atrial septostomy is performed routinely after birth, to ensure mixing of the blood at intracardiac level and discontinue the prostaglandin infusion. However, most would not advocate this due to the potential risk of complications in neonates that are otherwise stable. ! 2. Tricuspid or mitral atresia! 3. PA / IVS! 4. TAPVD with restrictive septum! 5. During hybrid procedures for HLHS syndrome! 6. -

Imperforate Anus Associated with Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return in Scimitar Syndrome

Aklilu et al. BMC Pediatrics (2019) 19:296 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1643-z CASEREPORT Open Access Imperforate anus associated with anomalous pulmonary venous return in scimitar syndrome. Case report from a tertiary hospital in Ethiopia Tamirat Moges Aklilu1* , Messele Chanie Adhana2 and Azmeraw Gissila Aboye3 Abstract Background: Scimitar syndrome is a rare form of partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage associated with pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure that may lead to death in the newborn infant. Although it is described with anomalies of the lung, heart and their vascular structure, extremely rare association with imperforate anus had been reported. The third case of Scimitar syndrome and imperforate anus will be reported in this case report. Case presentation: A 3 days old male neonate with imperforate anus presented with abdominal distention. Loop colostomy was done to relieve abdominal distension. The chest x-ray revealed a curved shadow on the right mid lung zone extending to the diaphragm abutting and indenting the inferior vena cava (scimitar sign). Abdominal ultrasound, transthoracic echocardiography and computerized tomographic angiography confirmed the presence of Scimitar vein and associated dextro-position of the heart, hypoplastic right lung, hypoplastic right pulmonary artery, secundum atrial septal defect with bidirectional shunt, patent ductus arteriosus, pulmonary hypertension, left superior vena cava, and systemic collateral arteries feeding the lower lobe of the right lung. The rare association of scimitar syndrome with imperforate anus is discussed. Conclusion: Scimitar syndrome associated with imperforate anus with and without VACTERL association has been reported previously only in four cases. The knowledge of association between imperforate anus and Scimitar syndrome helps for early detection and management of cases. -

Balloon Atrial Septostomy in Complete Transposition of Great Arteries in Infancy

Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.32.1.61 on 1 January 1970. Downloaded from British HeartJournal, I970, 32, X6i. Balloon atrial septostomy in complete transposition of great arteries in infancy A. W. Venables From Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia The results of 26 completed balloon atrial septostomies in complete arterial transposition in infancy are described, and complications discussed. Of 7 deaths following this procedure, 3 were clearly or probably related to it or to its failure to produce an adequate septal defect, while 4 were unrelated. Atrial perforations occurred on 4 occasions. Necropsy information regarding the defects produced by the procedure is given. Anatomical features of the fossa ovalis appear to determine the size of the defect created. The effect of the procedure is illustrated by photographs of representative necropsy specimens. Apparently adequate initial defects do not guarantee satisfactory long-term palliation, and 4 of iI infants followed for more than 6 months after effective initial palliation have required surgical procedures to provide more adequate atrial mixing of blood. Despite this, the procedure appears to offer considerable advantage over initial surgical procedures to create atrial defects. The value of palliative procedures in com- Subjects and methods plete arterial transposition is indisputable. From to mid-May I23 cases of trans- ig60 i969, http://heart.bmj.com/ Most commonly, atrial septal defects arz cre- position of the great arteries in infancy were diag- ated in order to increase effective pulmonary nosed in the Cardiac Unit of the Royal Children's flow. Since I966 the balloon catheter tech- Hospital, Melbourne. -

ICD-9-CM Procedures (FY10)

2 PREFACE This sixth edition of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is being published by the United States Government in recognition of its responsibility to promulgate this classification throughout the United States for morbidity coding. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, published by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the foundation of the ICD-9-CM and continues to be the classification employed in cause-of-death coding in the United States. The ICD-9-CM is completely comparable with the ICD-9. The WHO Collaborating Center for Classification of Diseases in North America serves as liaison between the international obligations for comparable classifications and the national health data needs of the United States. The ICD-9-CM is recommended for use in all clinical settings but is required for reporting diagnoses and diseases to all U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration) programs. Guidance in the use of this classification can be found in the section "Guidance in the Use of ICD-9-CM." ICD-9-CM extensions, interpretations, modifications, addenda, or errata other than those approved by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are not to be considered official and should not be utilized. Continuous maintenance of the ICD-9- CM is the responsibility of the Federal Government. However, because the ICD-9-CM represents the best in contemporary thinking of clinicians, nosologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians from both public and private sectors, no future modifications will be considered without extensive advice from the appropriate representatives of all major users. -

Images Paediatr Cardiol

W Boehm, M Emmel, and N Sreeram. Balloon Atrial Septostomy: History and Technique. Images Paediatr Cardiol. 2006 Jan-Mar; 8(1): 8–14. in PAEDIATRIC CARDIOLOGY IMAGES Images Paediatr Cardiol. 2006 Jan-Mar; 8(1): 8–14. PMCID: PMC3232558 Balloon Atrial Septostomy: History and Technique W Boehm, M Emmel, and N Sreeram University Hospital of Cologne, Germany. Contact information: N. Sreeram, Department of Paediatric Cardiology, University Hospital of Cologne, Kerpenerstrasse 62, 50937 Cologne, Germany Phone: +49 221 47886301 +49 221 47886301 Fax: +49 221 47886302 ; Email: [email protected] MeSH: Transposition of the great arteries, Heart defects, congenital, Catheter, invervention, Balloon atrial septostomy Copyright : © Images in Paediatric Cardiology This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Introduction “A technique for producing an atrial septal defect without thoracotomy or anesthesia is presented. It can be performed rapidly in any cardiac catheterization laboratory.” (William J. Rashkind, 1966)1 “...The initial response to this report varied between admiration and horror but, in either case, the procedure stirred the imagination of the “invasive” cardiologists throughout the entire cardiology world and set the stage for all future intracardiac interventional procedures – the true beginning of pediatric and adult interventional cardiology.” (Charles E. Mullins, 1998)2 The natural history of untreated transposition of the great vessels in the neonate is poor. Complete correction has been possible since 1959 with the atrial switch procedure, first described by Senning.3 Mustard simplified this method, reducing mortality rates to a reasonable level.4 Best results with both operations were achieved in children beyond six months of age. -

Echocardiographic Assessment of TGA After Atrial Switch Repair

Echocardiographic assessment of TGA after Atrial switch repair Session 6. Transposition of the great arteries Multimodality Imaging in ACHD and PH Annemien van den Bosch Erasmus MC, Thoraxcenter, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Transposition of the Great Arteries . Mustard and Senning operations establish appropriate connection - between systemic venous pathways and subpulmonic ventricle - between pulmonary venous pathway and the systemic ventricle . At the expense of a morphological RV support systemic circulation Atrial switch operation Mustard Procedure: Uses baffles made from Dacron, GoreTex or pericardial tissue to redirect flow Hans Hamer© Atrial switch operation Senning Procedure: Uses tissue from the right atrium and the atrial septum to redirect flow. Diagrams from Popelova et al Post-operative Sequelae Baffle problems . Baffle obstruction - SVC baffle obstruction more common following Mustard operation 5-10% superior, 1% inferior - PV baffle obstruction is more common following Senning operation . Baffle leaks - Small leaks are common and not haemodynamically 25% important, except in the case of cryptogenic stroke - Large leaks are rarer but important due to associated volume overload 1-2 re-op% Post-operative Sequelae . Systemic RV - Hypertrophy - Dilatation (lack of reference values for systemic RV) - Systolic function invariably deteriorates over time . Tricuspid regurgitation - TR is predominantly due to annular dilatation and is likely functional rather than due to primary organic abnormality. In rare cases, structural tricuspid -

Left Atrial Decompression by Percutaneous Cannula Placement While on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Brief Communications provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Left atrial decompression by percutaneous cannula placement while on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation Anthony M. Hlavacek, MD, Andrew M. Atz, MD, Scott M. Bradley, MD, and Varsha M. Bandisode, MD, Charleston, SC enoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation serially dilated with 10F and 16F transseptal sheath dilators. With (ECMO) is often used in pediatric patients with severe transesophageal echocardiography guidance, a 17F cannula was myocardial dysfunction, typically after cardiac sur- advanced over the guidewire into the LA and connected to the gery, or in patients with acute myocarditis. A problem venous ECMO circuit. Chest radiography confirmed resolution of Vfrequently encountered in these patients is left atrial hypertension, his pulmonary edema by the subsequent day. An echocardiogram which may result in pulmonary edema, ventricular distention, and revealed normalization of his LA size and an estimated LA pres- subendocardial ischemia.1,2 Decompression of the left atrium (LA) sure decrease to 18 mm Hg by Doppler measurement of the mitral will reduce diastolic pressures in the left heart, resulting in an regurgitation gradient. He remained on ECMO for 42 days until a improvement in coronary perfusion and lessen pulmonary edema. successful orthotopic heart transplant was performed. We describe the percutaneous placement of a venous cannula in the LA while on ECMO in a child with severe